Introducing NASA’s Curious Universe

Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. Join NASA astronauts, scientists and engineers on a new adventure each week — all you need is your curiosity. Visit the Amazon rainforest, explore faraway galaxies and dive into our astronaut training pool. First-time space explorers welcome.

About the Episode

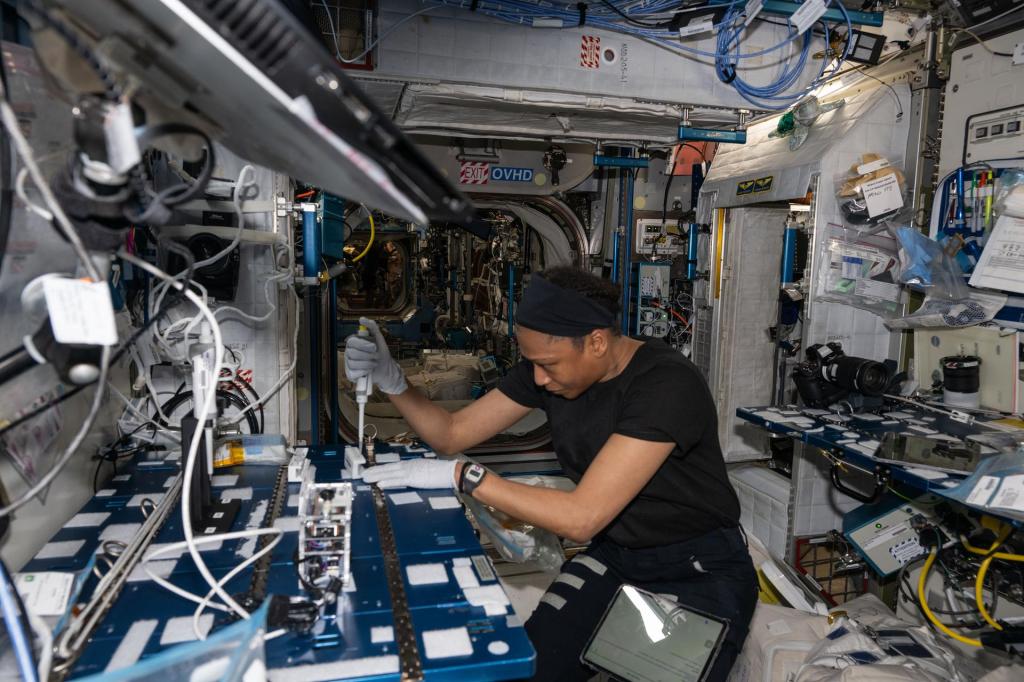

Orbiting 250 miles above Earth, astronauts aboard the International Space Station explore farther into our solar system and work on thousands of studies that will help us back here on Earth. Join ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti and NASA scientist Sharmila Bhattacharya on an adventure to our “orbiting laboratory.”

Subscribe

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: For the past 20 years we have been spacefaring civilization, which is, you know, something that when you say you kind of have to stop and let it sink in and, and, and realize that really it shouldn’t be taken for granted.

HOST PADI BOYD: Welcome to NASA’s Curious Universe. I’m Padi Boyd, and in this podcast, NASA is your tour guide!

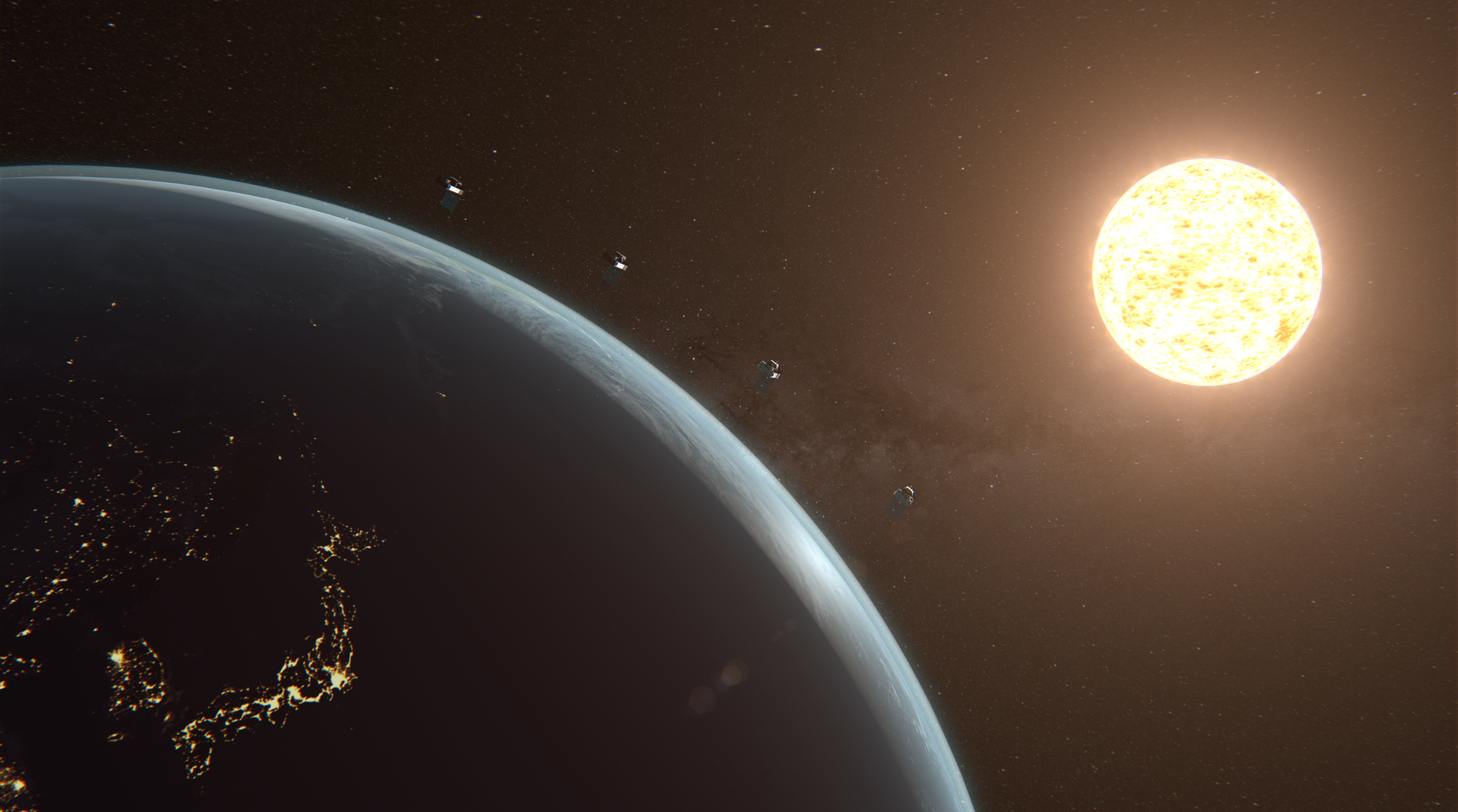

HOST PADI BOYD: 250 miles above Earth’s surface, a scientific laboratory orbits around our planet.

HOST PADI BOYD: Here, astronauts serve as the eyes and hands of researchers on the ground.

HOST PADI BOYD: This is the International Space Station. And 2020 marks the 20th year since the first humans occupied the space station.

[ARCHIVAL TAPE FROM 2000: 3,2,1. We have ignition. We have ignition and lift off. Beginning the first expedition to the International Space Station and setting the stage for permanent human presence in space ]

HOST PADI BOYD:…Following that first crew, there has been a continuous human presence aboard the station. So, if you were born after November in the year 2000, someone has been living in outer space throughout your entire life.

HOST PADI BOYD: Over 240 humans from 19 countries have lived aboard the space station, including European Space Agency–or ESA–astronaut, Samantha Cristoferetti (Cristo-for-ett-EE).

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: The international space station, the way I like to refer to it is humanity’s, outpost in space.

HOST PADI BOYD: In 2014, Samantha became the first female Italian astronaut, and the second ESA female astronaut to go to space.

HOST PADI BOYD: And once she arrived at the space station, she stayed for a long time, 199 days and 16 hours to be precise – hours spent aboard an ever-changing station with parts from around the world fit together like Lego pieces.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: It’s like big, soda cans. They’re called modules and they’re, like, joined to one another in what we call a stack.

HOST PADI BOYD: You might imagine the station as a cramped space.. But the way Samantha describes is like a really long hallway.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: Sometimes people tell you “how do you deal with claustrophobia or being confined in such a small space?” and I never had a feeling of being confined just because of how big and spacious it actually is. It’s gigantic, actually. If you were to lay it on the ground, it’s about as big as a football field. And of course, people float in it. So, you know, you’ll be floating around, you are inhabiting it in the three dimensions.

HOST PADI BOYD: Just a few hours from Earth, the space station whips around our planet in low Earth Orbit. The station, and everything inside, is in a constant free fall towards Earth. That’s why Samantha and her crew members float while aboard the space station. They’re experiencing something called microgravity.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI:…Which is nothing else than a fancy word to say weightlessness.

HOST PADI BOYD: Microgravity is what makes the International Space Station such a special lab and it’s a condition that you can’t simulate for long periods on Earth.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: There is no way of getting rid of gravity. The only thing that you can do is free falling. Uh, and so on earth, we can do it for a few seconds in drop towers. You know, you can, you can build a tall tower and drop things. And for a few seconds, guess what? They will be weightless, but eventually the ground, you know, they’re going to hit the ground.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: So, if you want that exposure to microgravity for a longer time, then the only way is to go, uh, in orbit. And so that’s, uh, that’s why we need the International Space Station.

HOST PADI BOYD: Microgravity changes everything — like the kind of physics you can observe and the way the human body operates. That’s why so many countries come together to oversee the orbiting laboratory. It’s a way for humans to do science that can’t happen anywhere else.

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s what astronauts onboard spend the majority of their day doing… working on experiments.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: You can go from doing investigations on human physiology, where the human being, the astronaut is actually the object of the investigation or plants, small animals, cell cultures, to the physical sciences… So, we have a lot of experiments on combustions on materials, on fluid mechanics.

HOST PADI BOYD: The work that a space station crew member does, conducting experiments in space, is not a solo operation. There’s a whole other team of people that design the experiments… people who have their feet planted firmly on the blue planet — like Sharmila Bhattacharya.

HOST PADI BOYD: Sharmila leapt at the opportunity to be a scientist at NASA because of the novelty of doing experiments in space and what her findings might mean for humanity.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: It’s something that you can’t easily simulate on earth. And what you usually find are so unique and different.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: Not only is there this factor of “oh my god” you know, look at these changes that we saw. Who would have thought? But there is another aspect to it. The science that you get from it helps us understand those physiological changes that are happening in humans better which means that it helps us come up with better countermeasures for astronauts and for the people who are going to be in space now and in the future.

HOST PADI BOYD: Sharmila studies the effects of space on the immune system. Our immune system is the way the body protects us against disease.

We know that when astronauts spend time in space, their immune systems get a little weaker. But we don’t yet know why!

HOST PADI BOYD: To understand this effect better, Sharmila and her colleagues use tiny research subjects that you might find in your own kitchen.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: The fruit fly, this unassuming little creature that will buzz around your rotting, bananas and so on, actually proves to be a very useful model organism for science in general.

HOST PADI BOYD: We share a lot of our genetic code with fruit flies. In fact, six nobel prizes have been awarded in physiology and medicine for discoveries made in fruit flies. But one of the main advantages of researching fruit flies is just the sheer number that you can use.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: We have sent up more flies into space then we have had humans.

HOST PADI BOYD: With astronauts, you may only have a few subjects to study, but with fruit flies, you can study thousands at a time and get a better understanding of how outer space affects animal biology.

HOST PADI BOYD: In some ways, the science Sharmila does is very similar to other biologists. In other ways it’s completely different. Like the moment when Sharmila must wave goodbye to her flies.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: I still remember the feeling that I had as I watched something that I had touched and worked on just a few hours before, be on this gigantic space shuttle that was, taking off in front of my eyes and going way beyond where we couldn’t see it anymore. Away far away from the surface of the earth. Up to that point, we had been busy in the lab.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: I wanted to make sure that the experiment was planned right and everything would go perfectly. So I had focused really more on the day to day of getting the experiment to work. And then on launch day, you get to for the first time, probably in days or weeks, or maybe even months, you get to release, sit down and take a deep breath and watch the launch in front of you. I remember feeling that Sonic boom, just sort of go right through my chest. And I remember thinking, this is why I do what I do, and this is why I work for NASA. And this is what makes all of that hard work, absolutely worth it.

HOST PADI BOYD: On launch day, Sharmila watched as parts of the experiment she spent months preparing soared out of her reach. But, in space, there was someone to greet Sharmila’s fruit flies and run the experiment – Samantha.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: It doesn’t happen every day that you get, you know, little flying animals on space station.

HOST PADI BOYD: Samantha had to help by collecting data, feeding the flies, taking pictures of the flies over time…And the fly lab had one essential piece of equipment that she had to keep an eye on…

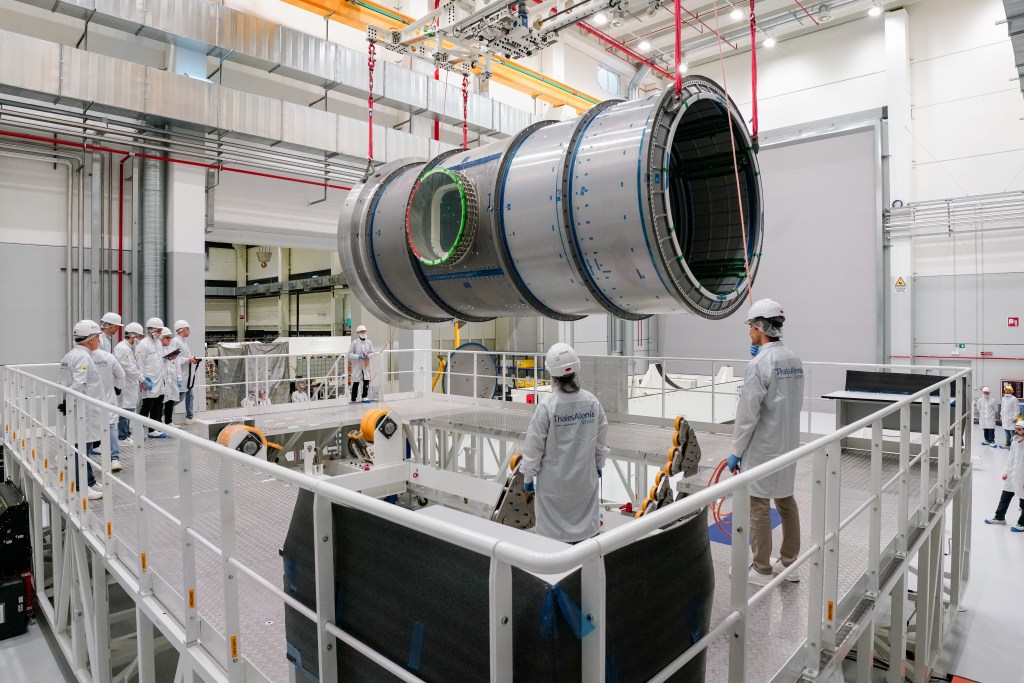

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: We had centrifuges – probably one of the most important aspects of hardware that we could use in science.

HOST PADI BOYD: The centrifuge is a machine that spins around and around like the amusement ride, the gravitron. You know, the one where people are standing on the edge, and spinning so fast that they all become a blur?

HOST PADI BOYD: In the gravitron, the force of the spin makes you feel like you can’t move, like you’re experiencing hyper-gravity. The centrifuge creates a similar effect.

HOST PADI BOYD: On station, there is so little gravity, that by using the centrifuge, you can mimic what we call “normal” gravity, the force of gravity felt on Earth. So to monitor changes that might happen due to space flight, it’s important to split the fruit flies into two groups.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI:…one set that would be in static positions and one set that would be in a centrifuge.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA:…to see what the actual changes were in space and what was contributed by gravity and what was contributed by the other factors.

HOST PADI BOYD: Without the centrifuge, Sharmila wouldn’t be able to conduct her research properly.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: Every now and then, just like it does on Earth, things don’t go the way that it’s been scripted.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: It turned out that the motor couldn’t quite get the centrifuge started.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: It was one of those small glitches that one could not predict, you know, the, just that one time the centrifuge decided it was not going to turn on.

HOST PADI BOYD: So Samantha started troubleshooting, seeing if anything was in the way of the centrifuge that could be stopping its motion. And the whole time she was communicating her process with people on the ground.

MISSION TAPE [Back on three for the centrifuge. Ground: Yea Sam, what did you find out? We didn’t really see anything conclusive Ground: Copy all, Sam, I think you’ve done as much as you can…]

HOST PADI BOYD: No luck there. But Samantha wasn’t giving up. She needed to think of something else.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: What the astronaut did, it was brilliant.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: I would have to kind of like find a way to go in and attach this piece of tape.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: She stuck it on the side of the centrifuge .

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: You know, kind of threading it out and reclose the rack.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: And she gave it a yank.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: A real nice pull.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: Just the way you would kickstart your lawnmower.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: And she got the centrifuge going. It turned. And there was no problem with the centrifuge thereafter.

MISSION TAPE [ It looks like it is working fine now. Ground: On behalf of all of the little fruit flies we thank you.]

HOST PADI BOYD: The fruit flies AND the scientists were thankful for Samantha’s quick thinking.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: Having the astronauts there to help us was a critical part of being able to do more complicated science, to get higher science yield out of the science that you were doing. And also frankly, they were incredible, uh, as people who were there to troubleshoot your experiments, should you need anything.

HOST PADI BOYD: The human ingenuity and ability to think on the fly is why humans will stay aboard the orbital outpost for many years to come.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: People sometimes make it a little bit too easy when they say we can replace all that by robots, we can do all that automatically. Maybe, possibly, you could do that. But then you really need to hope that you predicted everything… that nothing is going to go wrong.

HOST PADI BOYD: It’s the humans that make the space station, not the equipment itself. The people that, for the past twenty years, have been in space and on the ground designing the experiments and making sure everything goes smoothly.

HOST PADI BOYD: Together, they’ve made scientific discoveries about heart health, bone loss, growing plants in space, materials science… and they’ve worked on over 3,000 research projects. But there will be many more discoveries to come.

SHARMILA BHATTACHARYA: We’ve been doing genetics on the Earth for a little over a hundred years. If you compare that with the fact that we’ve been doing research on the international space station as a laboratory for less than 20 years, we have a lot more information that we’re going to find out, a lot more information that we’re going to need to find out, as well, in order to get us prepared for long term exploration. I mean, I think, frankly, that right now, we are just at the tip of the iceberg.

HOST PADI BOYD: What we’ve learned in the past twenty years goes even beyond the science. It gets to the heart of what makes us human, dreaming big and making those dreams a reality through collaboration.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: For the past 20 years we have been spacefaring civilization, which is, you know, something that when you say you kind of have to stop and let it sink in and, and, and realize that really it shouldn’t be taken for granted.

SAMANTHA CRISTOFORETTI: You know, I have great respect and admiration for the previous achievements of the past, you know, Apollo and the space shuttle, and so on. But, you know, people should not think that the space station is less than that. You know, we have demonstrated as a community for 20 years, we’ve shown every day that it is possible to live in space with continuity, without interruption, with an international community. And I don’t know how many people would have bet 20, 25 years ago that it was going to work in the end so smoothly. For me it’s just humbling to think that I had the privilege of being part, for a short time, of this amazing success story.

HOST PADI BOYD: During her stay on the orbiting laboratory, Samantha travelled 84 million miles and helped oversee almost 100 experiments.

HOST PADI BOYD: Sharmila continues to launch fruit flies into space where the latest rotation of station astronauts are there to greet them.

HOST PADI BOYD: Most of us won’t make it onto the space station, but that doesn’t mean we can’t see it. The big array of solar panels that power the station reflect some of the sun’s light. That means around dusk or dawn, you may be able to see it zooming through the sky.

HOST PADI BOYD: Human’s outpost and laboratory in space. A global collaboration that persists through conflict. A beacon of hope.

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. This episode was written and produced by Margot Wohl. Our executive producer is Katie Atkinson. The Curious Universe team includes Maddie Arnold, Micheala Sosby, and Vicky Woodburn.

HOST PADI BOYD: Special thanks to Erin Anthony, Rachel Barry, Ryland Heagy, Nicole Rose, the International Space Station Research Integration Office, and the European Space Agency.

HOST PADI BOYD: To keep up with current space station research, follow @ISS_Research on Twitter.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you liked this episode, please let us know by leaving us a review, tweeting about the show @NASA, and sharing with a friend.

HOST PADI BOYD: Still curious about NASA? You can send us questions about this episode or a previous one and we’ll try to track down the answers! You can email a voice recording or send a written note to NASA-CuriousUniverse@mail.NASA.gov. Go to nasa.gov/curiousuniverse for more information.

GARY JORDAN: Hey Curious Universe listeners, I’m Gary Jordan from NASA’s Houston We Have a Podcast. I hope you enjoyed this first episode of the new season of Curious Universe. We have some more great content coming your way so make sure you’re subscribed to Curious Universe to get the latest when they post. Maybe this episode has scratched an itch and you’re dying for more space between your ears this month.

GARY JORDAN: Well, you’re in luck, because Houston We Have a Podcast has some special content coming up just for you. This week and next we’re diving into the Crew-1 mission, the first crew rotation mission to the International Space Station on the SpaceX Crew Dragon. We’re talking with the astronauts flying on the spacecraft AND the flight director that’s leading the operations from mission control in Houston. Also, we’ll be posting double episodes — that’s right, two episodes per week – for the weeks leading up to the 20th anniversary of continuous human presence on the International Space Station.

GARY JORDAN: Stay up to date with us by subscribing to Houston We Have a Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, SoundCloud, and many other places, or go to nasa.gov/podcasts.

Looking for more information about the International Space Station?

NASA Explorers: Microgravity is a video series that gives you a behind-the-scenes look at the experience of sending science to the International Space Station. This laboratory offers something we can’t get on our home planet: Microgravity. Follow a team of scientists during their journey to launch their research off our planet to the space station, and to see what microgravity may reveal.

Want to watch the International Space Station pass overhead? It is the third brightest object in the sky and easy to spot if you know when to look up. Sign up for Spot the Station so you know when the orbiting lab is over your home.