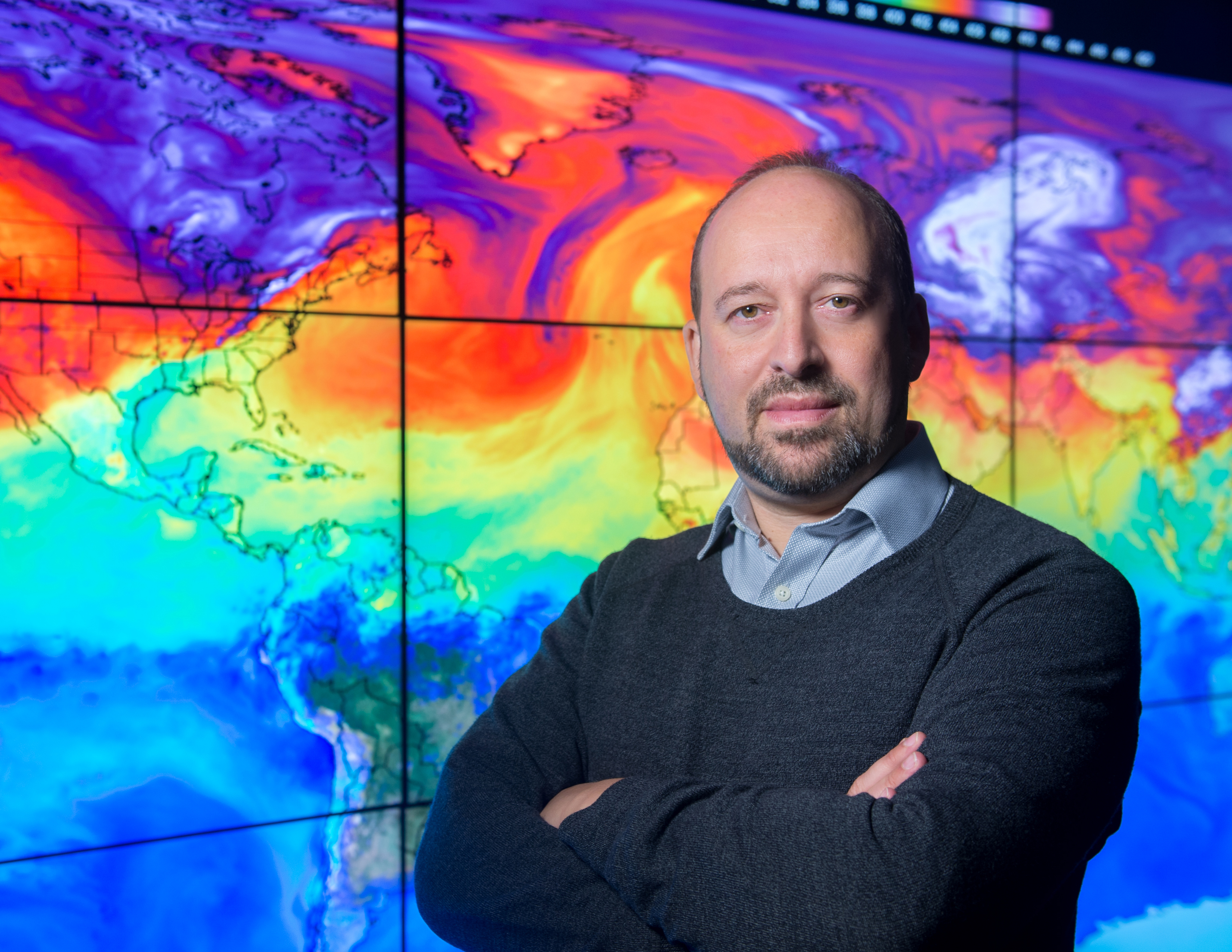

What’s the difference between climate and weather? How does NASA monitor changing sea levels, melting glaciers, and other effects of climate change? Gavin Schmidt, NASA’s acting senior climate advisor, explains how rising temperatures lead to many complex changes both in the oceans and on land. When it comes to climate change: “It’s real. It’s us. But we still have choices about how bad we let it get,” he says.

Jim Green:NASA has been observing the Earth from space for several decades and seeing some astounding changes.

Gavin Schmidt:It’s real. It’s us. But we still have choices about how bad we let it get.

Jim Green:Hi, I’m Jim Green. And this is a new season of Gravity Assist. We’re going to explore the inside workings of NASA in making these fabulous missions happen.

Jim Green:I’m here with Dr. Gavin Schmidt, and Gavin is NASA climatologist, climate modeler, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York. And he’s also a co-founder of the award-winning climate science blog Real Climate. But since February 2021, Gavin was named the acting senior advisor on climate to the NASA administrator. Welcome, Gavin, to Gravity Assist.

Gavin Schmidt: Thank you very much for having me.

Jim Green:So how would you describe the difference between climate and weather?

Gavin Schmidt: So people have come up with all sorts of great analogies to explain this difference. One of the ones that I like the best is thinking about your wardrobe. Right? So what you have available to wear any morning is, you know, there’s a lot of different things that you could, you could put on. And, and that kind of sets the choices that could happen in that day.

Gavin Schmidt: But what you actually put on is a unique outfit, right? It’s not necessarily going to be repeated, except kind of during the pandemic, when it’s repeated every day. Um, but you know, you have a, you have a change, that, that’s available, but, but you’re limited, right, you can’t just do anything. And then sometimes somebody can come along and buy you a new bunch of shirts. And now that’s, that’s closet change, right? And your and your choices then change and your and your choices for what you’re going to wear in any one day, can also change because, you know, things in your closet have changed.

Jim Green:Our planet has been through a lot of different climate changes in its history.

Gavin Schmidt: Right.

Gavin Schmidt:How do you study these more ancient periods, you know, like ice ages?

Gavin Schmidt: We’re continually searching the geological record, which, which consists of things like the ice core records, and ocean sediment records, and, and rock records, and pollen records and cave records, and all sorts of very inventive ways to get a sense of what’s happened in the past. And we’re looking for examples for where we have a potential mechanism for why climate changed. And then we have examples of how climate changed, and then we try and piece these things together such that, you know, we can ask that question, you know, does that cause, now which could be a massive asteroid, it could be wobbles in the Earth’s orbit, it could be massive volcanism, it could be a shift in the continents, do any of these causes lead you to see the changes that we’ve recorded in these other records, and when we can do that we gain both a deeper understanding of the things that cause climate change, but also more credibility in our ability to understand the things that cause climate change. And so we use, we use those changes in the past, to evaluate the models that we’re building for today, and to see whether they’re in the right ballpark, and, and they do pretty well.

Jim Green:So the phase of climate change that we’re in right now, why is that so different than the past?

Gavin Schmidt:Why is something that’s happening now so special? And it’s because, because we’re special. We’re notm we’re not the first species to have altered the composition of the atmosphere. I think that laurel goes to two cyanobacteria, some 2 billion years ago when, when they started producing massive amounts of oxygen. But, but right now, we are making, you know, geological scale changes to the atmosphere. We’ve increased the carbon dioxide concentrations by about 50%.

Gavin Schmidt:We’ve more than doubled methane concentrations, levels of water vapor are increasing at about 7% per degree of warming. We’ve had more than a degree Celsius of warming since the 19th century. And we’re seeing, you know, geologically significant shifts in, in the amount of glacial ice, in the amount of sea level, and the amount of, you know, temperature and, and the ecosystem responses to those things. And we can go back. And you know, in a lot of times, you’re seeing something that that is kind of unique, in a few hundred years, maybe unique in a few thousand years. There are some places where we can go now, like on Baffin Island in the Canadian archipelago, where we are seeing changes in the ice caps there that are revealing that these ice caps are melting, and they’re revealing surfaces that have not been exposed to the air, perhaps for 125,000 years.

Gavin Schmidt:Right? So, so we have pushing the system in ways that are, you know, quantitatively large compared to the history of the planet, and that that continues to blow me away. But things that things are shifting. So how do we know why that’s changing? That’s a great question.

Gavin Schmidt:And then, as you mentioned, you know, over the history of the planet, lots of things have caused climate change volcanoes variations in the sun, the wobbles of the Earth’s orbit, you know, changes in outgassing, the, the shape of the continents, where the continents are, the ocean circulation itself, all of those things have caused things to change. But we can, we can look and see what’s happened over the last 150 years.

Gavin Schmidt:And we haven’t had any big volcanoes, you know, we’ve had a couple, but we haven’t had massive, massive volcanoes. We haven’t had an asteroid. We haven’t had a big shift in the continents, they are moving very slowly. The Earth’s orbit does not wobble, you know, in some anomalous way. But what has happened is, we’ve increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, we’ve chopped down a whole bunch of forests, we’ve increased the amount of air pollution. We’ve irrigated, large amounts of land, and we can put all of those things in and ask the question, if only the natural things that happened, if only the volcanoes and the sun and the orbital walls, if only they had to change, where would we end up?

Gavin Schmidt:Where would we have ended up? And then you can say, well, if only the things that we’ve done, had changed, where would we have ended up? And then what happens when you put all of those things together, and it turns out, they kind of add up pretty linearly. And if you just look at the natural, forced changes, you don’t end up with very much change over the last 150 years. But when you put in the human cause of change, then it lines up with what we see. And not just in the surface temperature, but also in the changes of heat in the ocean, the changes in Arctic sea ice, the changes in the stratosphere, the changes in the tropics, that changes the pole, the changes on land versus on ocean, all of those things fit, right.

Gavin Schmidt:And the fingerprint that we see in all of those records, in all of those changes, is our fingerprint. It’s not anybody else’s, it’s not the Sun, it’s not the volcanoes, it’s us.

Jim Green:You know, there’s all kinds of natural things as you point out that happen year after year after year, like hurricanes or wildfires, but climate change is exasperating those. And how does that do that?

Gavin Schmidt:Going back to our, our closet analogy, it’s, it’s no, it’s like somebody is throwing out all the cold weather gear and just kind of stocking your closet with, with shorts and t-shirts. And things are things are changing and, and you know, not every day, you’re going to be able to pick out exactly what’s going to happen. But but we’re seeing, particularly with things like hurricane intensity, or rainfall intensity, drought intensity, with we’re seeing these being juiced by the changes in temperature. So increasing surface temperatures in the ocean leads to the possibility for more intense hurricanes. And so we’ve seen an increase in the, in the more intense hurricanes over, over the last 50 years, we’ve seen the heat waves are more intense and more and more frequent across a whole part of the Northern Hemisphere. We’re seeing that when it rains, it rains more intensely. And we’re seeing that not just as functions of the big storms, but, but more generally. And again, that’s something that’s due to the warmer sea surface temperatures.

Gavin Schmidt:I mean, some good news, we’re seeing less cold weather outbreaks, despite you know what happened in Texas this year, we are actually seeing less of those over time. And when they come they’re less cold. So you know, that’s moderately good news. We’re seeing extended growing seasons, also moderately good news. Unless, you know, you care about kudzu and pine bark beetles and invasive species and those kinds of things. But we, yeah, I mean, the changes that have happened so far with climate, are now evident in a whole suite of new variables, a whole suite of new extremes.

Jim Green:Well, as you say, we see those things because we can measure them here on Earth. But NASA has a really unique perspective. And that is from looking at it from space, and getting global ideas as to what’s going on. So what are some of the measurements, the important measurements that NASA’s Earth Science program is making that gives us an idea of what’s happening in the climate change area?

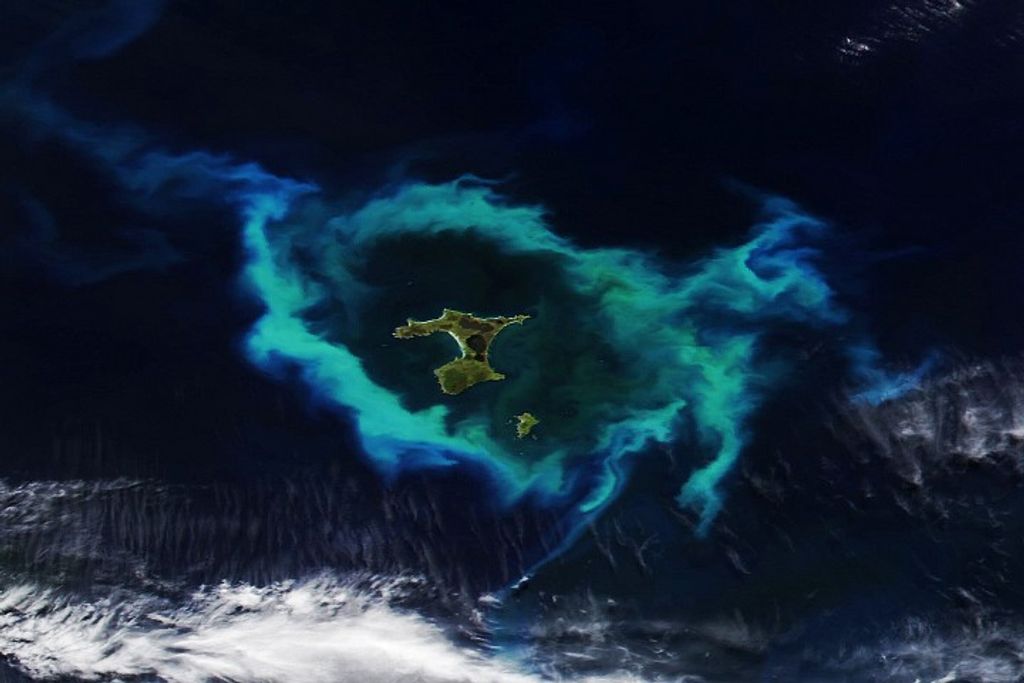

Gavin Schmidt: We have the trends in the radiation at the top of the atmosphere from, from the CERES measurements, we have the trends in Gravity from the GRACE satellites, and the GRACE follow on satellites. We have sea level rise from a whole series of laser altimeters, which we just launched the you know, I think the fifth in the series. We have a records of Arctic sea ice going back from 1979 onwards, where we can see very clearly how things have been have been changing. We can see the changes in ice itself from, from visual records from from Landsat, for instance, you know, we can see, you know, the, the decline in mountain glaciers in Alaska and in the Himalayas, and in the Rockies and in the Andes, and in the Alps, and on Kilimanjaro, and in Papua New Guinea, and all of the places where we have ice on the planet. We’re seeing changes that are consistent with the temperature changes, in temperature over this over this time period.

Jim Green: You know, one of the satellites I really like is ICESat and as you mentioned, it uses lasers that then allow us to determine height; laser altimetry, how does that really work?

Gavin Schmidt: Magic? How does that work? So it works because the satellite has has a laser on it. And we know the satellites position very, very accurately, it sends down a laser to the surface, and then it bounces back up, and how quickly it bounces back up is a measure of how far it’s traveled. And how far is traveled tells you how high the surfaces and the precision of these measurements allow us to at a global scale, you know, see clearly changes in the global sea level of a few millimeters per year. And, and allow us to see, you know, changes in elevation on on the on the ice sheets themselves of, you know, a few meters per year. It’s I mean, it’s really very impressive.

Jim Green: Yeah, remarkable set of measurements indeed.

Jim Green:So NASA just announced that we’re developing a new set of missions. We call them the Earth System Observatory. What are they all about? And what will they measure?

Gavin Schmidt: So this is a suite of new missions, that are partially to continue the series of measurements that we’ve been making over the last few decades, but also to measure important new things that we haven’t been able to capture. Before you know what one of those new things is really fine grained information about aerosols. So particles that are in the atmosphere, they’re made up of lots of different things, you know, dust and sea salts and sulfur dioxide and then sulfate particles and soot and pollen and all sorts of different things. But really getting an idea of where those aerosols are, when — it’s a very confused and complicated picture, we haven’t had that global view of that in enough detail up until now. So that’s going to be a big part of one of the new, one of the new missions.

Gavin Schmidt:We’re continuing to build on these, these gravity measurements. So that we can continue to track not just where the ice in Greenland and Antarctica is going, but also changes in groundwater, and changes in other kinds of, of water storage on on land, because that turns out to be really important, as well, oh, we have a one of these missions is to look at vertical land movement, which is so important for understanding how changes in global sea level are going to impact regionally in any particular location

Jim Green: So, in the monitoring that we do, are there measurements that we can make or are making that would help people understand the elevation of water and threatening of the ocean fronts that we have here on in the world?

Gavin Schmidt: Yes, and no. So measurements only tell us what’s going on right now. And and in order to prepare for what might happen in the future, you need models. But we are making we are making the measurements that feed into those forecast models. We’re looking at the satellite altimeter data that’s giving us regional sea level, you know, very close to the shore, we’re looking at the, the INSAR data and the NISAR data, there’s going to be upcoming, there’s going to tell us more about vertical land movement, which is which is the other part of risks associated with relative sea level change. So yes, you know, we are making those measurements, but they need to be fed into the analysis, they need to be fed into the modeling, so that we can project things going forward, that we don’t yet have observations for.

Jim Green: Well, to understand this concept of altitude of land isn’t it true that as, as ice or snow in mountain peaks then wither away, the land becomes more buoyant and moves up. And so you have to not only factor in the, the change in ocean height, but the change in, in mass that is occurring on the land.

Gavin Schmidt: Yes, you do. And in fact, it’s even more complicated and more fascinating. Because when you when you move the ice, when the ice moves, and it melts and goes into the ocean, you’re also changing the mass distribution on Earth, which changes gravity. And so if you lose a chunk of ice on Greenland, that means that there’s less gravity pulling water towards Greenland. And in fact, sea level goes down near Greenland, and goes up elsewhere. And, and it turns out that there’s a small change in the rotation of the Earth as well, which also changes the shape of the geode, and you need to have all of those things calculated, if you’re going to be able to predict what’s going to happen to sea level in New York, or in Johan– or in South Africa, or also or in or in Shanghai. And each of those places has a different fingerprint from where the ice is melting, or where the terrestrial water storage is changing.

Jim Green: Gavin, what lessons should we take away from the climate environment during the global pandemic?

Gavin Schmidt: Okay, so let me start off by saying that I’m not going to recommend a global pandemic in order to reduce emissions.

Jim Green:Good, good, good.

Gavin Schmidt: Nonetheless, the restrictions that were put in place, it did impact a lot of different emissions. So as you rightly say, you know, we, in the US, we reduced carbon dioxide by I think about 10%, in 2020, compared to the year before, globally, it was about a 7% decrease in carbon dioxide emissions, mostly from changes in transportation. So people weren’t driving as much they weren’t flying as much. And, and that had impacts on other things, too. So, so people not driving reduce the amount of nitrous oxides. So those are a precursor of smog, there are very bad, health wise, in cities, mostly everywhere, we saw reductions in ozone, and not, not so much in some of the most polluted parts, but, but we saw big changes in in the short-lived pollutants that we that we saw from space, everywhere, where there were big restrictions put in place.

Gavin Schmidt:So there’s, there’s two lessons, I think, to take from that. One is that just making people stay at home and not do anything, is not a good climate plan. Right? That’s, that’s, it’s not sufficient. The systematic changes that need to be made in how power is generated and how industry is run. Those are the big players and, and without tackling those, you know, individual choices about you know, working from home or going into the city or taking a car or taking a bus taking a bike, all of those things are small comparatively.

21:25 Gavin Schmidt:The second thing to learn from that, though, is that anything that we do that is going to reduce emissions is always going to affect these other things. It’s also going to affect air pollution, it’s also going to affect smog. And there are things that we can design there are, there are policies that we can design that allow us to reduce emissions and clean up the air at the same time, and reduce, you know, public health problems associated with particulates or with ozone or with smog. And so these things are connected. And I think the, you know, one of the most important lessons from, from the COVID pandemic has been: Those connections are very, very clear. And we need to be able to build those into our, our plans going forward.

Jim Green:So in terms of being a good steward of this planet, are there things that individuals could do that would help out?

Gavin Schmidt:It’s important to remember that even though you’re an individual, you wear many hats, you know, you’re, you’re an individual consumer. You’re a commuter, you can, you can work from home or take a bike or take public transport, rather than driving a car, you can swap out your car for an electric vehicle. You can be a citizen, you know, you’re you can be a parent, you can be a member of a faith community. And through those communities, you can influence decisions that are being made at a higher scale, right? You can influence the, the insulation that that’s being put into the school or your new building, you can influence where your town buys its energy, you can influence the politicians that are making decisions about utility choices, you can influence, you know, the readers of your local newspaper. You can influence the people at your local town halls, you have a lot of different roles that are there that can amplify your values and your choices, such that they can impact bigger and bigger and bigger decisions.

Jim Green:So everyone can play a role and an important one at that.

Gavin Schmidt:Yep.

Jim Green: Well, you know, Gavin, I always like to ask my guests to tell me, what was the event or person, place, or thing, that got them so excited about being the scientists they are today? I call that event a gravity assist. So Gavin, what was your gravity assist?

Gavin Schmidt:So back when I was a postdoc, I was working at McGill University in Montreal. And Montreal, as I’m sure you know, is is bilingual, right? So there’s, there’s an English population, there’s a French speaking population. And I’m fortunate enough to speak a little bit of French and so I was able to kind of, you know, go between the two. And, and I remember, you know, pretty early on, when I was there, I was giving a talk, and it was a, it was a French language scientific conference, and I was giving a talk on the Cretaceous, and what, and how the climate of the Cretaceous might have been. And immediately after I gave my talk this, this, this, this journalist came up to me and, and he said, Oh, you know, I’m from from Radio Canada, which is the French, the French network there.

Gavin Schmidt:And he says, you know, my audience is absolutely fascinated by by the Cretaceous, you know, because, you know, there were dinosaurs, and everybody loves dinosaurs. And, and he said, You know, I just, you know, can you tell me something about the predictions? So, he, you know, the camera starts rolling. And this is all in French. And the guy says, What would he says to me, you know, “Comment était le crétacé?” So, what was it like in the Cretaceous? And I said, “Chaud.” Hot. And he says, you know, how hot? I said, “Très chaud,” very hot. And he said, Thank you very much. And that was it. And I was going, Okay, well, that was that was that was interesting.

Gavin Schmidt:And, and, you know, and I bring that up, because, you know, what’s kind of pushed me to be kind of where I am, as has been a kind of innate desire to help people out to explain stuff to folks. And one of the things that I realized at that moment was that even if I don’t know everything, I still know a lot more than a lot of other people. And that’s kind of the need to know a lot about the need to know a lot about a lot of things, and see how they fit together. And then be able to explain what’s going on in the ocean to the people that care about the clouds, or what’s going on in the radiation to the people that care about paleoclimate or explained to somebody that cares about the dinosaurs how climate change, you know, impact or impacted or impacted them. You can be that translator, you can be that conduit of interesting information. You know, that was that was when I kind of realized that that was something that could be done. And that, and that I could do it.

Gavin Schmidt:What’s pushed me into climate change has been both that kind of evolution of, of my thinking about what science is for, but also this massive interest that the public and another people have about climate change.

Jim Green:Well, I gotta tell you, you really upped your game since that last interview. (laughs)

Gavin Schmidt:Well, it’s a craft, yes.

Jim Green:Yeah, that’s right. And and indeed it it takes a lot of practice and a lot of exposure. And, and it’s hard for scientists to talk about, you know, some of these esoteric subjects.

Jim Green:So Gavin, thank you.

Gavin Schmidt:Thank you very much.

Jim Green:Will join me next time as we continue our journey to look under the hood at NASA and see how we do what we do. I’m Jim Green, and this is your Gravity Assist.

Credits

Lead producer: Elizabeth Landau

Audio engineer: Manny Cooper