On a quest to find out if we are not alone in the universe, Ravi Kopparapu at NASA Goddard studies how we could use telescopes to detect signs of life beyond our solar system. These include both signs of biology and technology, since there are certain kinds of signals and chemicals that do not occur naturally. Learn about the planets that are most exciting to Ravi and how science fiction inspired his journey to become a scientist.

Jim Green: Is there intelligent life beyond our solar system? And how are we ever going to find it?

Ravi:No one signal is a good signature of technology or biology. You need a combination of things.

Jim Green: Hi, I’m Jim Green, and this Gravity Assist, NASA’s interplanetary talk show. We’re going to explore the inside workings of NASA and meet fascinating people who make space missions happen.

Jim Green:I’m here with Ravi Kopparapu. And he is a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who thinks a lot about the signs of life and what they might be on a planet outside our solar system. We call that planet an exoplanet. Ravi makes climate models of exotic faraway worlds and investigates how we could detect biology, but also technology, coming from these exoplanets. Welcome, Ravi, to Gravity Assist.

Ravi Kopparapu: Thank you, Jim. I’m super excited to be here.

Jim Green: Well, you know, I heard that you used to study something completely different: gravitational waves. What are those? And, and why did you stop working on that particular topic?

Ravi Kopparapu:Yes. (laughs) So I did my PhD in physics, in the field of gravitational waves. To give a brief summary: Imagine you’re throwing a rock into a clear water. And the ripples after you throw the rock into the water, the ripples coming from there are essentially what we think of as gravitational waves coming from an object. Any object in this universe has gravity. And so gravitational waves are essentially when you have a moving object, they’re very dense moving objects, going around each other, or, you know, exploding stars. They emit these spacetime waves, you know, Einstein theorized that there could be spacetime, right? So these are the spacetime waves traveling across the universe.

Ravi Kopparapu: Why did I leave this field? I was at Penn State working as a postdoc on gravitational waves. But at that time, I heard about this new field of science that’s just coming out exoplanets. And I was like, Okay, wait, this sounds interesting. And the main thing I wanted to do is that, can I explain my work to my mother? And if she asked me, “Hey, Ravi, what are you doing?” And I’ll say, “Oh, I’m working to find alien life.” And that’s simple for me to explain to her. And it was exciting. And my daughter used to say that, you know, “my dad finds aliens.” I felt like a Hollywood star. And so I thought, “Okay, let’s go ahead and do it.” And then that’s how I started.

Jim Green:Well, that’s fantastic. But you’re really doing it in a very important way. And that is looking at atmospheres of exoplanets, and not just any old atmosphere. How did you end up making that decision?

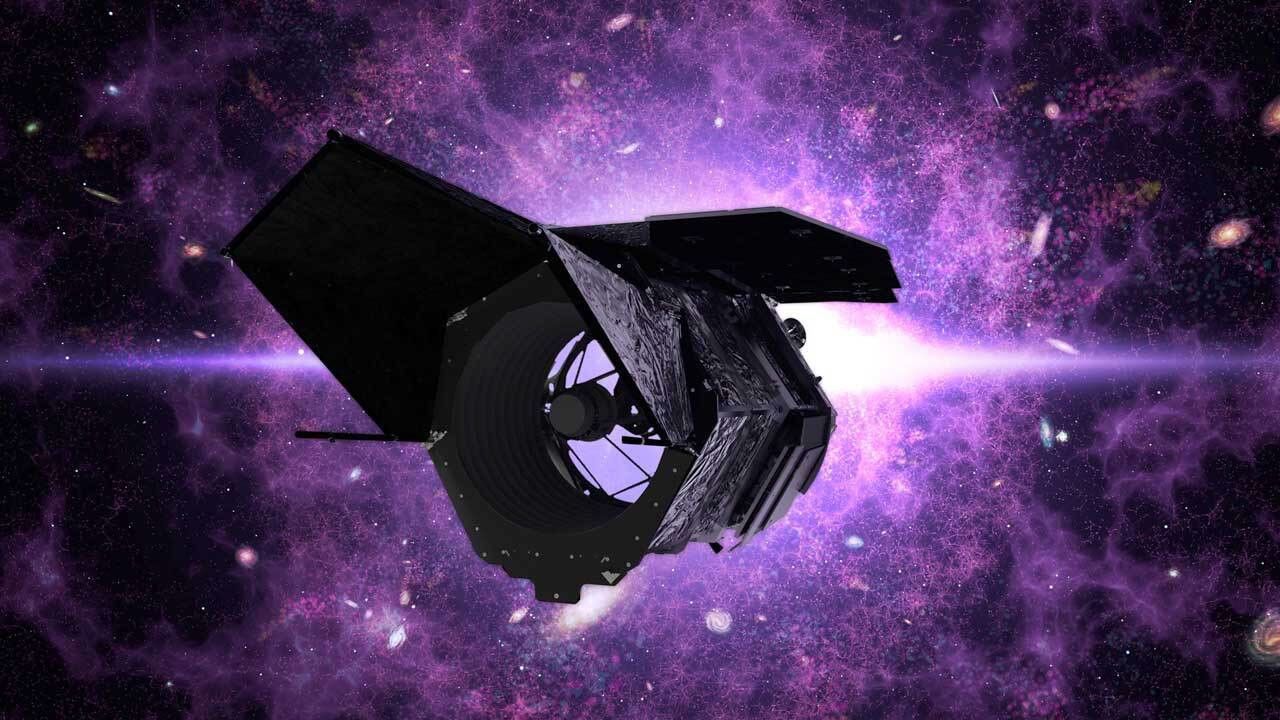

Ravi Kopparapu:Right. So the reason why I study these atmospheres of exoplanets is because I think, the ultimate goal of answering the question, “Are we alone in this universe?” with the existing telescopes and existing instruments, is to look at the atmospheres of these exoplanets because they’re so far away, it’s really not likely anytime soon for us to travel to those planets, right? And so the best thing we can do at this point is to point our telescopes collect the light coming from the atmospheres of the planet, and then look [at] what kind of gases they are. And that was exciting to me. And so I started working on the climate models of these planets.

Jim Green:Well, why do you think, and I believe it’s the majority of planetary scientists and astrophysicists think that there could be complex or intelligent life on planets beyond our solar system?

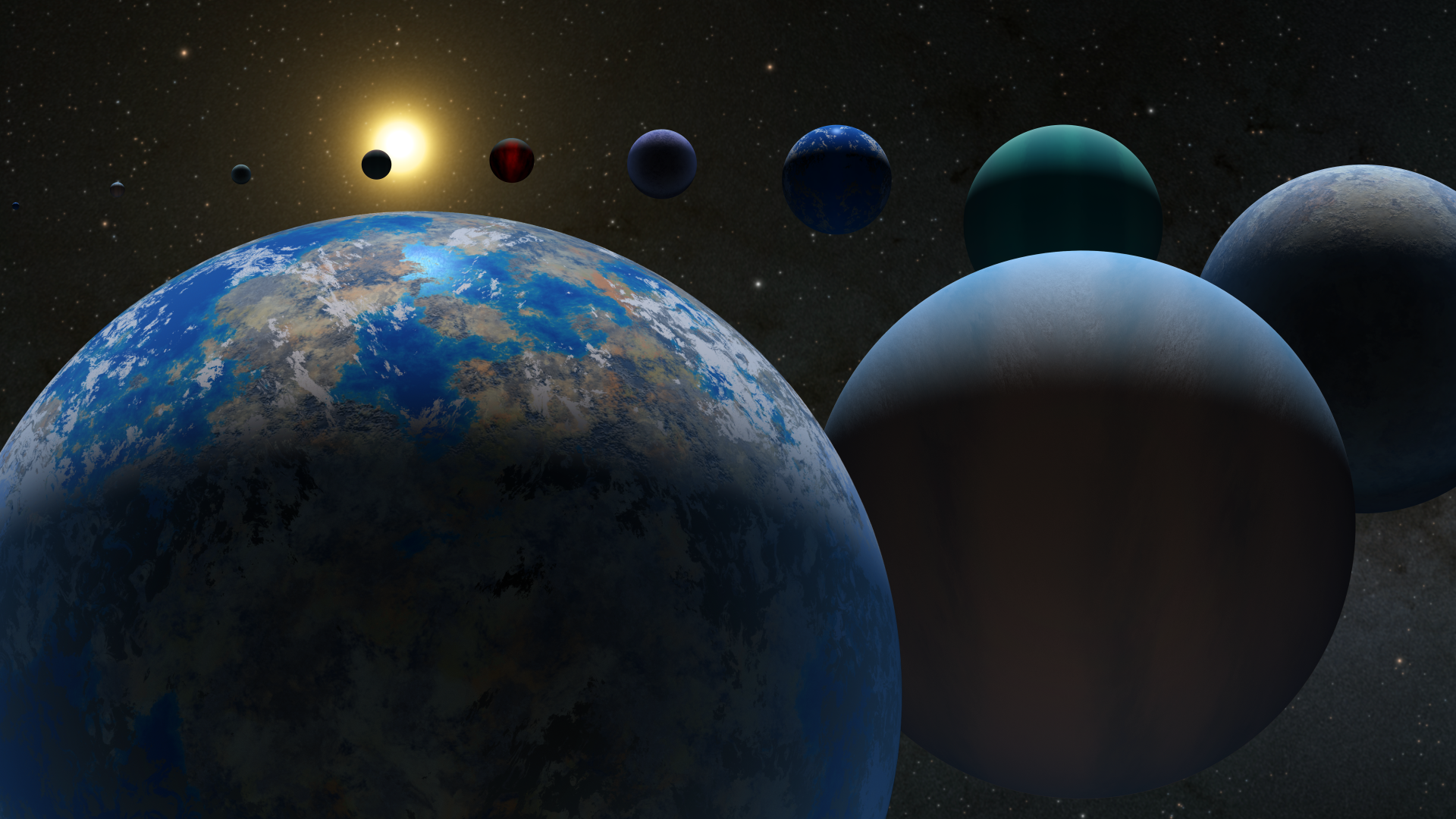

Ravi Kopparapu:So, just to give you an idea, right now, we know more than 5000 exoplanets, planets orbiting other stars. On average now we think there is at least one planet for every star in our galaxy. And our galaxy has at least a minimum of 100 billion stars. So there are at least 100 billion planets in our galaxy. And imagine the statistics of having so many planets around in our galaxy, and many of them could be smaller, Earth sized planets that could host life.

Jim Green:Well, I know you’ve done some really fascinating work on exoplanet climate models. What are some of the climate conditions you expect on these exoplanets?

Ravi Kopparapu:If you asked me this question, 30 years ago, I would say oh, all of them are going to be Earth-like, conditions or maybe you know, Jupiter-like planets, because how else plants are going to form other than our solar system arrangement, right? I mean, come on. Everyone should look like us. Right?

Jim Green:Right. Right.

Ravi Kopparapu: Of course.

Jim Green:(laughs)

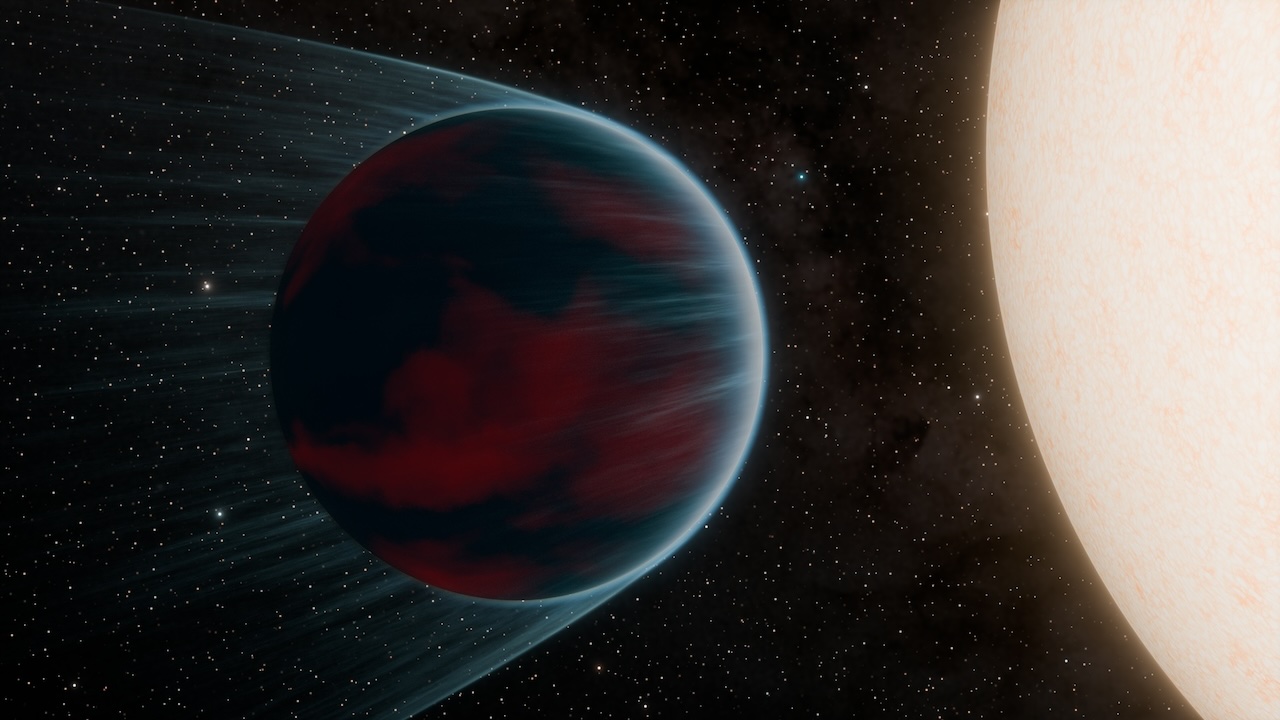

Ravi Kopparapu: But then what guess what happened in 1995? When they first found the exoplanet the first exoplanet around a sun-like star, it’s a Jupiter sized planet, in a four-day orbit around a sun like star.

Jim Green:Wow.

Ravi Kopparapu:Yes. And it was unexpected. And that’s why we wanted to see how these planet conditions are going to change from star to star. What we are seeing is only a small subset of the climate conditions that we are discovering right now. Super-hot, small-size, planets, large size planets, and also habitable Earth sized planets are also we found them and with lots of different kinds of missions. One important thing though, Kepler Mission, which was launched in 2009, found that the most common type of planet is some were in between Earth and the Neptune size. And we don’t have that in our solar system.

Jim Green:So yeah, we call that a super-Earth or a mini-Neptune.

Ravi Kopparapu:Exactly.

Jim Green: Yeah. So something happened as our planets evolved, that that one of those didn’t form. Well, what do you think that was?

Ravi Kopparapu: Those kinds of planets are somewhere in between, transitioning between a gas giant and a rocky planet. They don’t have as dense atmospheres as Jupiter or Neptune, or they don’t have completely thin atmospheres like our Earth. They have somewhere intermediate between both the planets. They may have little of hydrogen, little of, you know, carbon dioxide or ammonia, but not too much, not too little.

Jim Green: Yes, that’s what makes them fascinating, that we don’t see them in our own solar system, but we can see them around other stars. Well, are there any exoplanets that you’re really excited about right now?

Ravi Kopparapu:Yes, actually. Our closest star is Proxima Centauri. And four or five years ago, astronomers have discovered a planet, an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone around Proxima Centauri. It’s called Proxima Centauri b. So this is what I’m really excited about, that opportunity right now.

Jim Green: Well, that star and the planet is only about 4 light-years away. There’s another planetary system a little further that I’m also excited about and that’s TRAPPIST-1, and that’s it about 40 light-years away. What can you tell us about the TRAPPIST-1 system of planets?

Ravi Kopparapu:So you asked if I’m excited, and what kind of a planet I’m excited about. I said Proxima Centauri b. Well, we won’t be able to characterize or at least look at the atmosphere of the planet in the next decade or so. But for TRAPPIST, we have James Webb Space Telescope up there, and it is one of the primary targets in the habitable zone planets with James Webb Space Telescope. So there are seven planets in that system.

Ravi Kopparapu:TRAPPIST-1 system has three habitable zone planets in it.

Ravi Kopparapu:We would like to see if the planets themselves can retain the atmosphere, because the star is pretty small. And these small stars usually have very high flaring and ejections of very high intensity X-rays and the UV rays. So we would like to see, first of all, do they have any atmosphere? And if they do, do they have water-based atmosphere? Because water is essential for life.

Jim Green:It turns out that star, as you said, is a small dwarf star, those planets are really close. And like our Moon, are they tidally locked? Do they always have one face pointing to the star, and the other pointing away?

Ravi Kopparapu:Yes, they are tidally locked. In fact, I would even go ahead and say they are synchronously rotating. Essentially what it means is what Moon is doing to us, always facing the same side of the planet to the star. And because of that, so this is exactly what I do in my research work in my climate modeling. We model these tidally locked planets around these cool stars. And, and because these planets are tidally locked, or synchronously rotating facing only one side all the time, the the climate and the weather is completely different than what how we have it on Earth. For example, if you’re on that planet, there is always a thick cloud cover right in front of the Sun side of the planet, always all the time. And because of that, that cloud will try to protect or at least try to not increase the surface temperatures as much as it would have if you if you don’t have the cloud cover. And so the climate is totally different.

Jim Green:What is the concept of this habitable zone around a star?

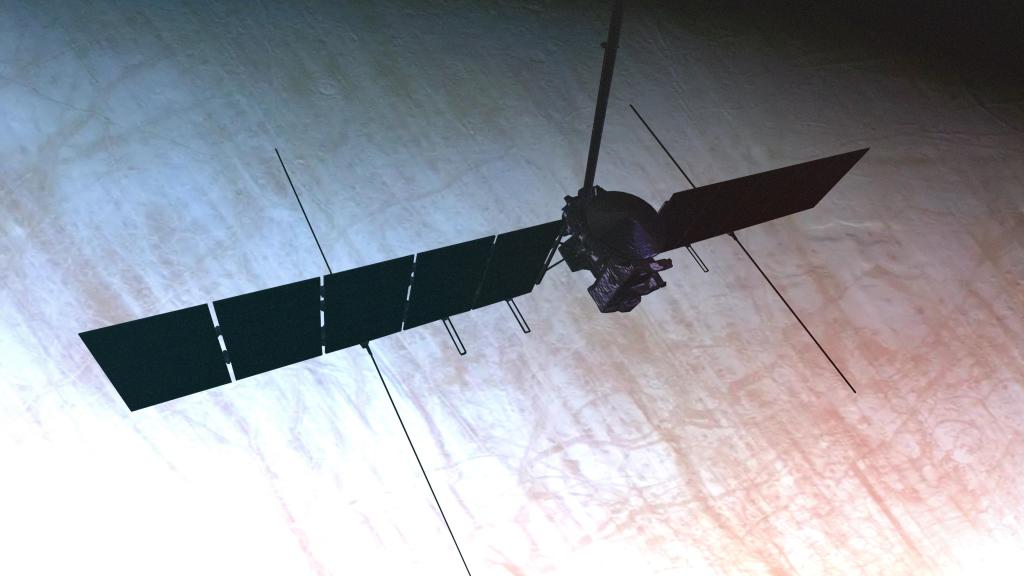

Ravi Kopparapu: So the way we define in the exoplanet field, the habitable zone is, it’s the region around a star, where a rocky-size planet with suitable atmosphere also has liquid water on its surface, and you can see how I carefully try to craft this definition. Well, liquid water is essential for life. And so we want to see if there is liquid water on the planet. Why surface? Why not subsurface? Well, these planets are exoplanets. They are quite far away from us. So within our solar system, there are Jupiter’s moons and Saturn moons where we think there are, there is subsurface, liquid water. So we have the luxury of sending missions to those planets and see if we can find the water under these moons. We don’t have that kind of luxury for exoplanets. So we have to focus only on the surface liquid water. And that’s the reason why we focus habitable zone concept on that.

Ravi Kopparapu:We have to understand that our Earth’s example is only one possible way of having life and intelligent life. So every planet’s evolution would be different. So that that that’s something that when we have to look when we are looking for exoplanet life.

Jim Green: Yeah, in fact, one can also think that we actually co-evolved with the Earth. We were in the right place, the right time, our moon helped us in many different ways. Our climate was great. And that really enabled us to develop into intelligent beings. This brings up a really fascinating topic in that is, how might we detect signs of technologies developed by intelligent beings on other planets around other stars? And we call that technology technosignatures. So what kind of technosignatures should we be looking for?

Ravi Kopparapu: So we know already one technosignatures that several of our colleagues are doing the radio technosignatures, radio, it’s called a SETI search for extraterrestrial intelligence. There are other ways that we can do, for example, pollution on the planet produced by industrialized civilizations. Maybe they have some sort of laser pulses sending as a beacon towards us. We can also detect them with the night-side city lights. Every civilization needs energy to produce and you know, to sustain. If we can build a telescope and look at the planet and if we detect nightside city lights, we know a that’s one of the technosignatures. So there are several of them like that.

Ravi Kopparapu: Chlorofluorocarbons, the CFCs that we use in our refrigerants, there is nothing in the nature that we know of, and that we can think of that can produce CFCs naturally, biologically, or hey, even abiotically. There is only one way to do that. And that’s through technology — that we know of.

Jim Green:That begs the question then, what would be the next set of observations you would then make?

Ravi Kopparapu: Okay, this is even, another excellent point. No one signal is a good signature of technology or biology, you need a combination of things, okay.

Ravi Kopparapu: So if you find CFCs [chlorofluorocarbons] and you think, oh, maybe that’s a technology, then you want to find corresponding other kind of pollutants in your data. And maybe for that you need to have a different kind of a telescope to do that, because not everything will be seen at the same time. And so if you find several different signatures of gases, if you do find other pollutants, then you know, hey, you know, there’s something going on that planet. Yeah, that’s great.

Ravi Kopparapu:One of the important things that we have to do is to remove or identify false positives.

Jim Green:Now, what do you mean by that? (laughs)

Ravi Kopparapu:Ah, that’s a good point. And, and also false negatives. I’m going to say about both them,

Jim Green:Okay, okay.

Ravi Kopparapu:Okay. The false positive is that you detect a signal, and you think it is your, the signal that you want, you know, “I found an alien technosignature or something.” But then it turns out to be out something the nature produced, or maybe some instrumental problem. So that’s a false positive. False negative is, you detect something, and you say that, “Oh, it’s instrumental noise. It’s nothing there. It’s from coming from the star.” But it actually is a signal from the thing that you want to detect!

Jim Green:Yeah, I’m concerned about that, too, as you probably know. You know, we have to be able to be confident, you know, create a level of confidence in each one of the observations. But what’s exciting about the field is, we make these analyses on signals, we get that out, the scientific community thinks of new and inventive and creative ways to either disprove the idea or enhance the idea. And that’s the process of science that we want to have.

Jim Green:Well, I have to tell you, you know, they’ll come a time when we may have to say we’re very confident that we have seen signs of extraterrestrial life. Do you think we humans, as a civilization here on Earth, are ready for that news?

Ravi Kopparapu:I think we are ready.

Jim:(laughs)

Ravi: I one-hundred-percent believe we are ready. And I’ll tell you why.

Jim Green:(laughs) Okay, because I’ve been asked that. And I’ve said I don’t think we’re ready. So, so I’m very fascinated to hear your response.

Ravi Kopparapu:Okay, so I like to say this: With the discoveries of exoplanets and with the discoveries of, you know, habitable zone, Earth, with water on Mars, and every aspect of science, we are not suddenly breaking out. It’s not 30 years ago, if you say that, Oh, we found a life on other planets, then everybody — “Oh, what? What did you do?” So here we found we are saying that okay, we found several thousands of planets. We are inching closer and closer. So we are getting everyone ready to accept to the point that “hey, you know, just, we are finding lots of neighborhoods, we are finding lots of houses. It’s just a matter of time before we find people in those houses.”

Jim Green:Okay.

Ravi Kopparapu: So I think we are ready.

Jim Green:All right. I don’t think we’re ready. And the reason why is I’m not sure what the observations are that will be the smoking gun that tell us what we’ve really found when we actually make the announcement and that’s going to require a lot more educating everyone as to what we’ve really measured and why we really think we have a high level of confidence to determine that it’s life.

Ravi Kopparapu:Okay, that’s a scientists’ problem.

Jim Green:(laughs)

Ravi Kopparapu:Not the general public’s problem. (laughs)

Jim Green:(laughs) Okay, okay.

Ravi Kopparapu:(laughs)

Jim Green:Well, you know, I’ve also heard that you’ve been involved in looking at unidentified aerial phenomena or UAPs. And and you’re approaching that from a scientific perspective, of course. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Ravi Kopparapu:So this is what I say, when we talk about the UAPs and search for life. They are two completely independent topics. We cannot combine them, unless we have super compelling information that, okay, they are somehow connected. For me, the search for life is what we just talked about all this time, exoplanets and telescopes and instruments and whatever. UAPs are something that are in our skies, and we don’t know what they are.

Ravi Kopparapu:And essentially, that’s where I stop and say, okay, because we don’t know what they are, we have to observe them with different instruments, collect the data, analyze, and then you figure out what they are. Apart from that everything else is speculation. And this is what I call a scientific applying a scientific methodology to studying the UAPs.

Jim Green:These UAPs may not be technological in nature. The many possibilities are atmospheric events or other natural phenomena. We just don’t know yet.

Jim Green:Well do you have enough data to make a determination? Or do we still lack a lot of knowledge and observations of UAPs, to make a determination?

Ravi Kopparapu: I think we do need a lot of data, collection of data, before we do any kind of determination. And that’s where we are right now collecting the data.

Jim Green: Well, Ravi, I always like to ask my guests to tell me what that person place or event was that got them so excited about being in the sciences that they are today. And I call that event a gravity assist. So Ravi, what was your gravity assist?

Ravi Kopparapu:My gravity assist, there were two of them. One, before I entered my PhD program. I’m a big fan of Star Trek. And I felt that that was a community where I could relate to and I wanted to study life from, you know, other planets. And that really, really motivated me since I was in eighth or ninth grade. And, and that really motivated me to pursue science, math, physics, and I was told to do well in those to become a scientist. And I kept that goal all the time, all, all through my life.

Ravi Kopparapu:The second one was had that happened about nine years ago, when I was writing a paper and the paper was about how common earth like planets in our galaxy. And I found, I did some calculation, I found that they are more than what I expected, and I literally jumped out of my chair, like, literally. I was like, “This can’t be possible. I’m standing in front of history that’s happening right now that we will for the first time in our life, we know, how common are Earth-like planets.” And and that really motivated me to study. You know, how do we find even more out? Okay, if they’re so common, where can we find this life? And that’s really motivated me to pursue more and more opportunities. And that’s why I’m at NASA Goddard, because this is where the missions happen. This is where we try to find life on other planets. And that’s, that’s my second gravity assist, I would say.

Jim Green: Well, that’s fantastic. You know, your excitement about the science and the things that you learn propel you to keep going and accelerate you. And hopefully, you will be the one to announce that we have found life beyond Earth.

Ravi Kopparapu:(laughs) Oh, I hope you will be with me at that time, Jim.

Jim Green:I’ll at least be able to interview you. (laughs) Well, Ravi, thanks so much for joining me for this fantastic look at finding habitable worlds in other solar systems.

Ravi Kopparapu:Oh, thank you so much, Jim. This is wonderful. Thank you.

Jim Green: Well, join me next time as we continue our journey to look under the hood at NASA and see how we do what we do. I’m Jim Green, and this is your Gravity Assist.

Credits

Lead producer: Elizabeth Landau

Audio engineer: Manny Cooper