PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY

NARRATOR

Just south of the equator lies a tiny plot of volcanic soil, a thousand miles from the nearest continent. The island sits about midway between the horns of Africa and South America. In 1501, Portuguese admiral Jose de Nova Gallege stumbled upon it en route to India, but left it unnamed. Two years later, Portuguese general Afonso de Albequerque happened upon the island and named it for the date on the Christian calendar: the Feast of the Ascension.

For the next three centuries, not much happened on Ascension Island. The only abundance it possessed was in volcanic features, about 38 dotting its 34 square miles. There was almost no vegetation, very little wildlife, and not much in the way of natural resources… Charles Darwin, who landed on the island in the course of his travels, called it a “desolate scene.” It’s an apt description when compared to the verdant Galapagos of Darwinist fame.

Ascension Island eventually found a purpose; in fact, a wide variety of them. During Napoleon’s exile on nearby St. Helena, the British established a naval garrison of 150 personnel to prevent use of the island as a base for Napoleon’s rescue. The aptly named “comfortless cove” — a place that sounds like it belongs in a Lemony Snicket novel — served as quarantine for sailors felled by yellow fever. At the turn of the 20th century a cable relay station was established, followed by a BBC transmitting station in the 1960s. The island became relevant not for its centrality or resources, but because it was so remote.

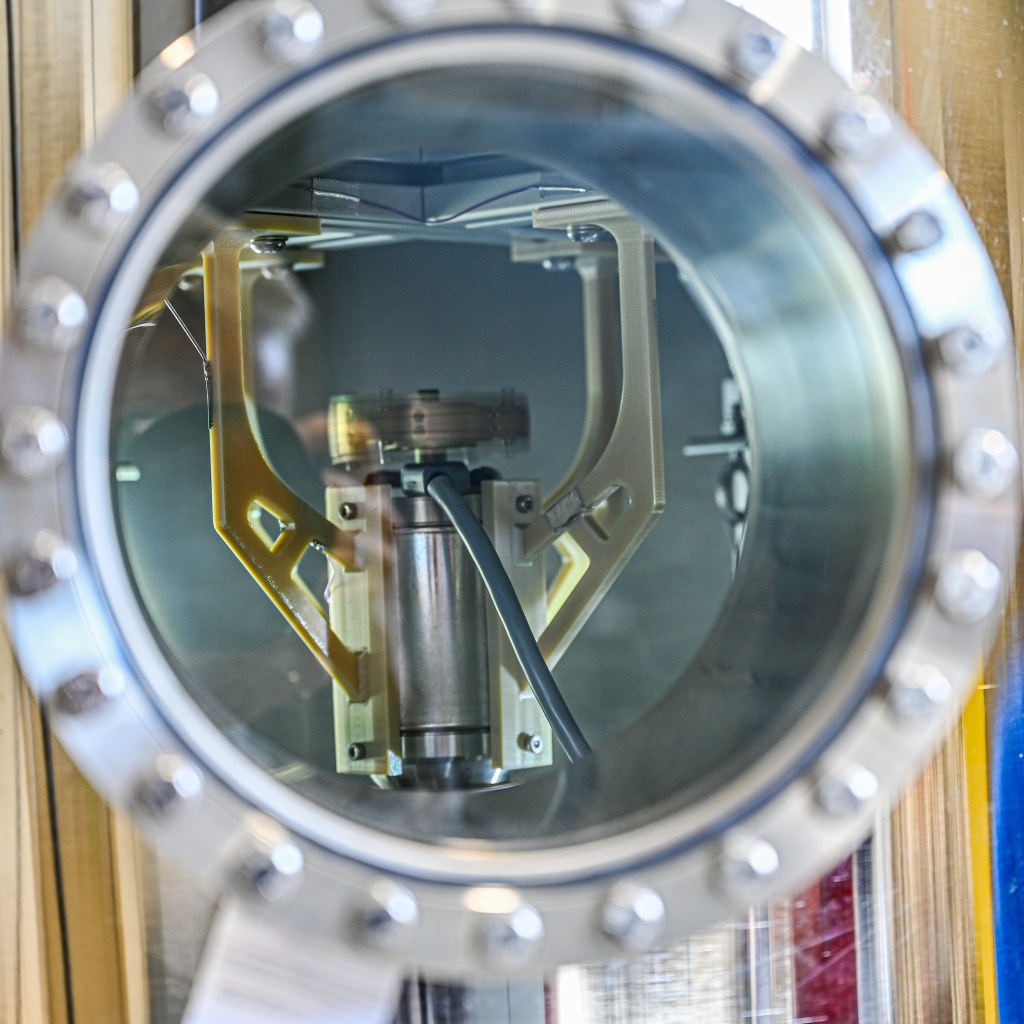

On Cat Hill, between a volcanic gorge of black cinder nicknamed “the devil’s ash pit” and the near-circular Cricket Valley, rest two antennas with diameters of 30 feet and a smattering of squat beige buildings. A large mountain separates the station from the rest of the island, limiting noise and interference. This bizarre, remote terminal had mammoth importance to America’s first efforts in space. It served the predecessors of today’s networks, tracking the Surveyor missions, the first American spacecraft to land softly on the lunar surface, and the near-Earth phases of the Apollo missions, America’s first efforts to place humanity among the stars.

I’m Danny Baird. This is “The Invisible Network.”

…

Some things work so well they render themselves invisible. We don’t think about the interstate until traffic clogs the path ahead. We don’t think about electricity until a felled tree leaves us in the dark. We take for granted innovation, technology and infrastructure that feels to us more certainty than miracle.

Smart phones, the internet, GPS, satellite radio: none of these technologies existed a mere 30 years ago, yet in many ways we don’t acknowledge their impact on our day-to-day lives. I don’t think it’s necessarily a lack of appreciation on our part; but rather a forgetting. We forget how far we’ve come, the technologies that move us forward, the advances that provide us with these common extravagances.

…

A cloud of smoke; the roar of engines; the gasp of the gathered crowd; mere mortals shucking off gravity’s inexorable pull; human spaceflight has always captured popular imagination and attention. NASA’s communications networks: oft forgotten… perhaps because they work so well.

In the earliest days of human spaceflight, NASA astronauts in cramped quarters had very little contact with Earth. NASA could only communicate with orbiting assets for 15 percent of each revolution around the globe. They relied on ground station antennas positioned in distant and often remote locations. It wasn’t ideal — but it was the reality.

When John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in 1962, NASA had already established 30 ground stations over five continents. Ships in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans supplemented their coverage. About half of the stations were used to support the burgeoning human spaceflight program. As Glenn whipped through the skies overhead at 17,000 miles per hour, these stations would track the Mercury capsule that housed him, passing communications from station to station, to station, to station…

The network that supported Glenn would undergo rapid change throughout the 1960s. To support the growing role of human spaceflight within the national zeitgeist, the NASA tracking station on Ascension Island was born.

Ascension’s antennas, about 5,000 miles downrange of Kennedy Space Center, were the first to view spacecraft after launching from Cape Canaveral in Florida. The telemetry received by the Ascension terminal would be used by NASA to compute trajectory and predict tracking for the rest of the stations within the network. They also provided in-flight checkout for Apollo spacecraft before injection into lunar transfer orbit, a crucial step on the journey to the Moon.

…

NASA presents employees who contribute profoundly to flight safety and mission success with a Silver Snoopy. The sterling silver lapel pin, designed by Charles Schultz, creator of the Peanuts cartoons, features Snoopy, Charlie Brown’s pet beagle, in an astronaut suit. Each pin flies aboard a human spaceflight mission and is personally presented to the employee by a NASA astronaut. They are presented to less than 1 percent of the aerospace workforce per year.

In the early days of our networks, the Silver Snoopys were still in their infancy. However, the Ascension terminal’s employees had their own Snoopy, a dog who came to live with them.

In 1969, at 3 years old, Snoopy bunked with Harry Turner, an employee in charge of Ascension’s track data and antenna position programming. Snoopy would wake Harry at 6 a.m. and they’d head to the NASA site for breakfast. Snoopy always rode shotgun. He’d lean into the road’s curves long before they came. After hundreds of trips to and from the terminal, he had it memorized.

Snoopy served as the station’s doorman, giving everyone a lick and a handshake after they gave him the passcode: “Whip one on me.”

There’s a lot of pressure for the men, working long hours in service to America’s goals in space. Snoopy provided much needed levity. Anything short of perfection could mean life or death for the astronauts they tracked. They’d go about their work, perhaps taking breaks to play with Snoopy, and return to the barracks on that same winding trail with Snoopy riding shotgun.

Beyond their work, Ascension provided little leisure. For Snoopy, there were sheep to chase, fields to run through, tug of war to play… But for its denizens? Ascension Island was designated “singles-only,” the sole piece of NASA’s early human spaceflight network not to allow families. It was too remote.

Ken Griffin, currently an employee at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, worked at the station between 1987 and 1989.

KEN GRIFFIN

I still have my Ascension Island driver’s license. It’s a paper booklet; no pictures. We were co-located with the Brits and it was a British Island, so everyone had to drive on the wrong side of the road. And life was very different there.

You had to get along without a lot of diversions, without the amenities of big cities or towns. You could hike and do other outdoorsy things like fishing or diving — and there were a few shops on the island, but not many.

And the other part of the hardship was that you were away from friends and family – it was an unaccompanied assignment. And it was hard to be separate from them when you had big events and milestones going on like holidays and birthdays.

NARRATOR

It took a lot of sacrifice to give astronauts the coverage they needed. Sacrifice surely worthy of a Snoopy — silver or otherwise.

…

In the following decades, the Snoopy of Charles Schultz fame would become the symbol of flight safety and mission success. Snoopy, the dog of Ascension Island, would be forgotten… and Ascension Island: soon after.

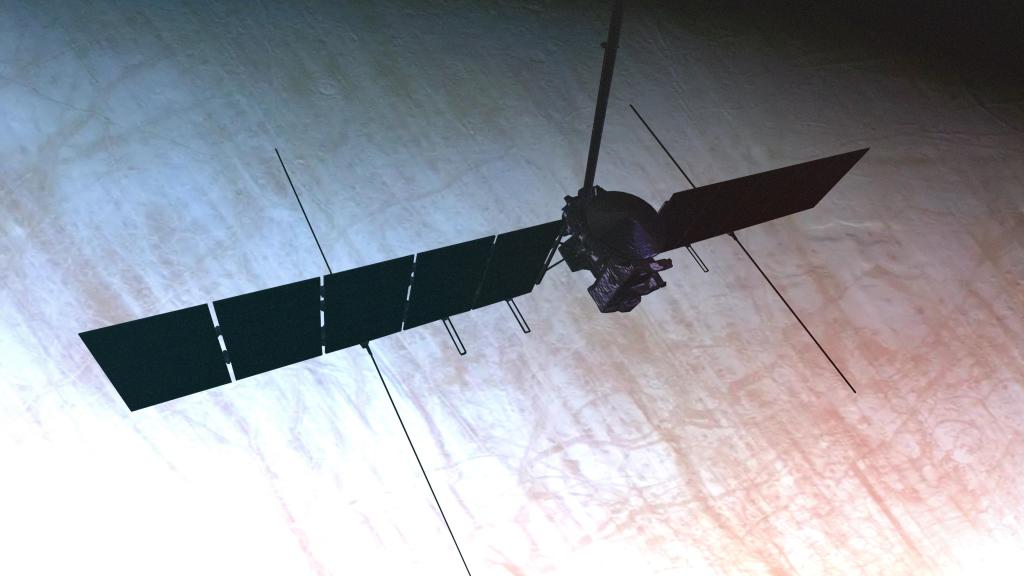

NASA envisioned a future where our astronauts were never alone in the void; a future that rendered Ascension Island obsolete. In 1983, NASA launched the first Tracking and Data Relay Satellite into geosynchronous orbit. After a second became operational, NASA could communicate with most spacecraft for all BUT 15 percent of their orbit, a far cry from the mere 15 percent a ground station could provide. With the 1998 activation of a remote ground terminal in Guam, NASA closed that “zone of exclusion,” providing over 99 percent data coverage.

Nowadays, astronauts aboard the International Space Station enjoy nearly continuous communications with Earth, giving astronauts a range of capabilities including transference of high-resolution science data, contact with their loved ones and ultra-high-definition video feeds. They can even live stream the Super Bowl in their personal time. The constellation of Tracking and Data Relay Satellites, our Space Network, make this miracle of modern technology possible.

NASA has by no means eliminated the need for a network of ground stations, though. NASA’s Near Earth Network has ground stations over all seven continents, serving NASA missions from low-Earth orbit to a million miles away.

Though an expansive piece of infrastructure, the Near Earth Network doesn’t require the same investment of human capital the early networks required. Many of the ground stations are commercially operated. Others, like the one at McMurdo Station, Antarctica, are operated remotely from the Global Monitor and Control Center at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. This ground network remains a robust, efficient option for NASA missions.

Deep space communications also require ground antennas. The Deep Space Network uses antennas up to 230 feet [70 meters] in diameter to communicate with missions as far away as Voyager 1, over 13 billion miles from Earth.

The network’s employees, for the most part, work only daylight shifts. Unlike the early days of the network, control of the Deep Space Network “follows the Sun,” alternating between its three ground stations in Spain, Australia and California as warm daylight shines overhead. Most employees no longer have to be nocturnal creatures, tracking satellites in the dead of night.

…

The August 2017 launch of the last in the third generation of the Space Network’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellites closed a chapter in this era of space communications. Their legacy will continue into the future, supporting missions as NASA develops next-generation infrastructure. Future Earth-relay satellites may integrate optical communications, artificial intelligence, quantum encryption and a bevy of other forward-thinking innovations.

Today’s networks hardly resemble those that supported Apollo — tomorrow’s networks, even less so. On our journey to the Moon, Mars and beyond, NASA must research ever bolder innovations in communications technologies to keep our astronauts connected to Earth.

Humanity may never lose our sense of wonder regarding exploration beyond our world. However, we take for granted the invisible foundations of spaceflight: those seemingly unsexy feats of engineering, research and personal sacrifice that make it all possible.

In this podcast, we manifest the invisible.

…

Ascension Island has changed a lot in the half-millennium since Jose de Nova Gallege landed on its craggy shores. Nowadays, Comfortless Cove is a popular beach. The British Garrison houses gift shops instead of soldiers. The island boasts the “worst golf course in the world.” Putting greens are crushed lava smoothed with oil. Large boulders frame the fairways.

A mountain still rises above the clay-colored expanse. It was born barren but now blooms green with vegetation. Human tampering in the island’s ecosystem turned wasteland to jungle. Many consider this centuries-long, semi-purposeful transformation a terrestrial analogue for potential Martian terraformation.

One could still reach the island by boat, but most fly. They go through “Wideawake airfield,” so named for the nearby colony of sooty terns, seabirds that circle overhead, filling the air with their cacophonous chattering. An airstrip there, Detachment 2, served as an emergency landing site for astronauts during the shuttle era. Should an orbiter have encountered an issue and needed to land on Ascension, NASA would dispatch a response team to the island within 24 hours.

Fortunately, this contingency measure was never called upon.

As for NASA’s ground station: In 1990, NASA abandoned the site in favor of newer, better infrastructure. The Ascension Island Operations building is one of the last vestiges of the original Manned Space Flight Network. Most have been destroyed. It now sports a painted camouflage of red, white and blue atop its faded beige. It belongs to the Ascension Island Boy Scouts, who use it as their Challenger outward-bound centre.

Visitors can still access the station’s deserted antennas; view the remnants of once-vital infrastructure. It’s beautiful desolation: a lonely monument to an invisible network that has served (and will continue to serve) humanity on our mission to place ourselves among the stars.

…

The Invisible Network is a NASA podcast presented by the Space Communications and Navigation program. This episode was written by me, Danny Baird, and released on Oct. 16, 2018. Editorial oversight provided by Ashley Hume. Our public affairs officers are Clare Skelly and Peter Jacobs. Make sure to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts and share us with a friend. For the full text of this episode, a list of sources and related images visit nasa.gov/SCaN.