Dec. 2, 1990:

The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) at Marshall receives a call from STS-35 mission specialist Robert Parker, in orbit aboard space shuttle Columbia, marking the first ever direct communication between the HOSC and astronauts on orbit. The exchange signaled the start of NASA’s first Astro Observatory mission: multiple anchored, high-powered telescopes, mounted on a Spacelab pallet in the shuttle’s payload bay. Astro-1 consisted of three ultraviolet telescopes and an X-ray telescope. During that initial mission alone, the telescopes enabled 231 observations of 130 unique astronomical targets. In 2021, a team of Marshall engineers and retirees collected and refurbished the groundbreaking hardware for the Smithsonian Institution to grant Astro a distinguished place in its National Air & Space Museum annex at Dulles International Airport in Washington, where some 60,000 daily travelers can see it on display next to space shuttle Discovery.

Jan. 1, 1991:

After NASA created its Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) program in 1990, weather and climate research begins in earnest at Marshall with the establishment of the Distributed Active Archive Center, better known to weather forecasters and researchers today as the Global Hydrometeorology Resource Center (GHRC). A comprehensive, living data archive focusing on hazardous weather, the GHRC contributes to NASA, NOAA, and international research on lightning, tropical cyclones, hurricanes, and other storm hazards by compiling and integrating collections of satellite, airborne, and in-situ datasets. The GHRC is maintained by Earth scientists and climatologists at NASA and the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), working in the National Space Science and Technology Center on the UAH campus.

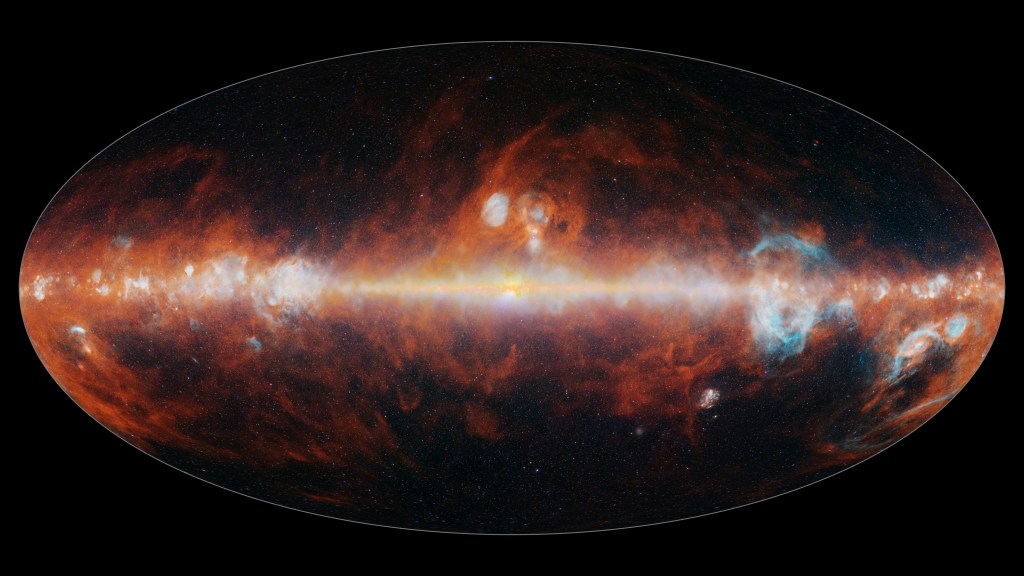

April 5, 1991:

The launch on this date of NASA’s Compton Gamma-ray Observatory includes the Burst and Transient Source Experiment (BATSE) designed, developed, and built in-house at Marshall. BATSE studied some of the most energetic phenomena in the cosmos, primarily the random, daily, titanic gamma-ray bursts which BATSE proved were occurring in the most distant parts of the observable universe – the nearest on record taking place more than 100 million light years from Earth. BATSE remained in operation until June 2000.

Jan. 22, 1992:

The first International Microgravity Laboratory (IML), managed for NASA by Marshall, launches aboard space shuttle Discovery during the STS-42 mission. Dedicated to the microgravity study of fundamental materials science and life sciences, IML-1 was a joint endeavor involving more than 200 scientists from 16 countries, including Canada, Japan, France, Germany, and other European Space Agency partners, and helped paved the way for the international coalition that made the International Space Station a shared scientific success.

Feb. 3, 1994:

The Shuttle-Mir program officially begins with the launch of space shuttle Discovery on STS-60, carrying among its eight-person crew Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev. Marshall was involved in the program every step of the way, managing the Mir Operations Support Team, which included a payload engineer, biomedical engineer, flight surgeon, crew interface personnel and science coordinator. The program, designed to foster a new era of international partnership in space nearly four decades after the start of the “Space Race” between the United States and Russia, included joint Spacelab experiments, regular video linkups between the space shuttle and crews in the Russian space station Mir, and routine crew exchanges with that orbital research platform as well. By the time the program ended in 1998 – making way for construction of the International Space Station – American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts had shared 11 shuttle missions, one joint Soyuz flight, and nearly 1,000 days of living and working together in space.

July 16, 1994:

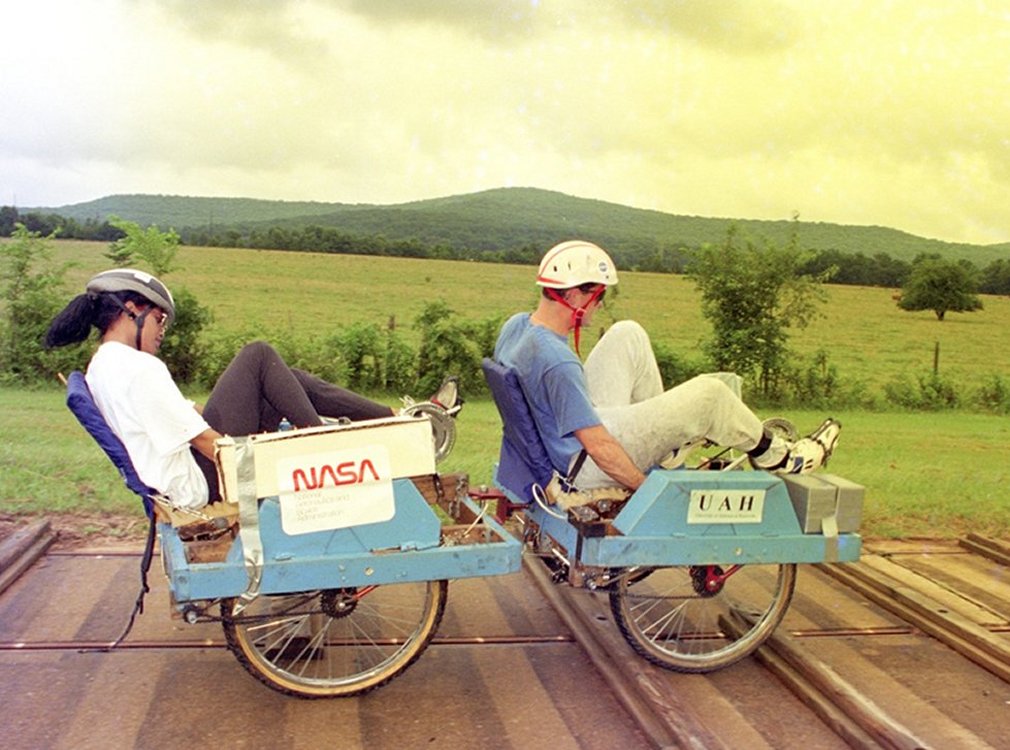

Marshall hosts the first NASA Great Moonbuggy Race, which 20 years later would evolve into the NASA Human Exploration Rover Challenge. Just eight college teams competed in the first race, driving lightweight “moonbuggies” of their own design around the same dirt course at Marshall where engineers tested the Apollo-era Lunar Roving Vehicles. The University of New Hampshire won the inaugural challenge with a course-completion time of 18 minutes and 55 seconds, for which they received a trip to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center to see a space shuttle launch. Today, as many as 100 teams of high school, college, and university students from all over the world participate annually, designing and building their own human-powered rovers to negotiate a course at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center that simulates the geographical and technological challenges of exploring the Moon, Mars, and other worlds.

April 3, 1995:

The Optical Transient Detector, a cutting-edge optical and electronic global lightning mapper developed at Marshall and built in partnership with the University of Alabama in Huntsville, is launched to geostationary orbit aboard the MicroLab-1 satellite. The instrument remained in operation through March 2000, offering unprecedented insight into lightning activity and its relationship with tornados, hurricanes, and other severe weather. The detector identified differences between cloud-to-cloud and cloud-to-ground lightning strikes, verified that lightning occurs over land 10 times more often than it does over water, and revealed that lightning strikes somewhere on Earth approximately 1.4 billion times each year. It helped set the stage for more sophisticated lightning and severe weather monitoring flight instruments, many of them built and flown by Marshall investigators.

Nov. 27, 1997:

Continuing Marshall’s successful lightning studies, NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission satellite is launched on this date from Tanegashima Space Center in Japan. It carries the Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS), a space-based instrument developed at Marshall to further clarify the relationship between lightning and severe weather and to enable real-time updates to forecasters, significantly improving severe weather “nowcasting” to protect lives, property, and resources. The LIS instrument flew as part of the TRMM mission until 2015. A second Lightning Imaging Sensor was launched to the International Space Station in 2017 and remains active today.

Dec. 4, 1998:

Unity Node 1 module – the first U.S. component of the International Space Station – is launched aboard space shuttle Endeavour as part of the STS-88 mission, set to be mated with the Russian Zarya Control Module, launched two weeks earlier on Nov. 20. The Unity and Zarya modules were officially mated in orbit on Dec. 6, marking the official beginning of station assembly, which would continue through 2011 and require more than 50 flights to deliver living modules, laboratories, and hardware to orbit and resupply the rotating crews. The Boeing Co. of Huntsville built Node 1, the Destiny laboratory module, and the 6-ton Joint Quest Airlock at Marshall. The critical Unity module functioned as a central junction and anchor point for the station, featuring six berthing ports to connect adjoining modules as assembly progressed. Marshall and its Boeing contractors also designed the Common Berthing Mechanism, the innovative linkage that physically connects all station elements, including the Japanese and European modules and visiting commercial spacecraft.

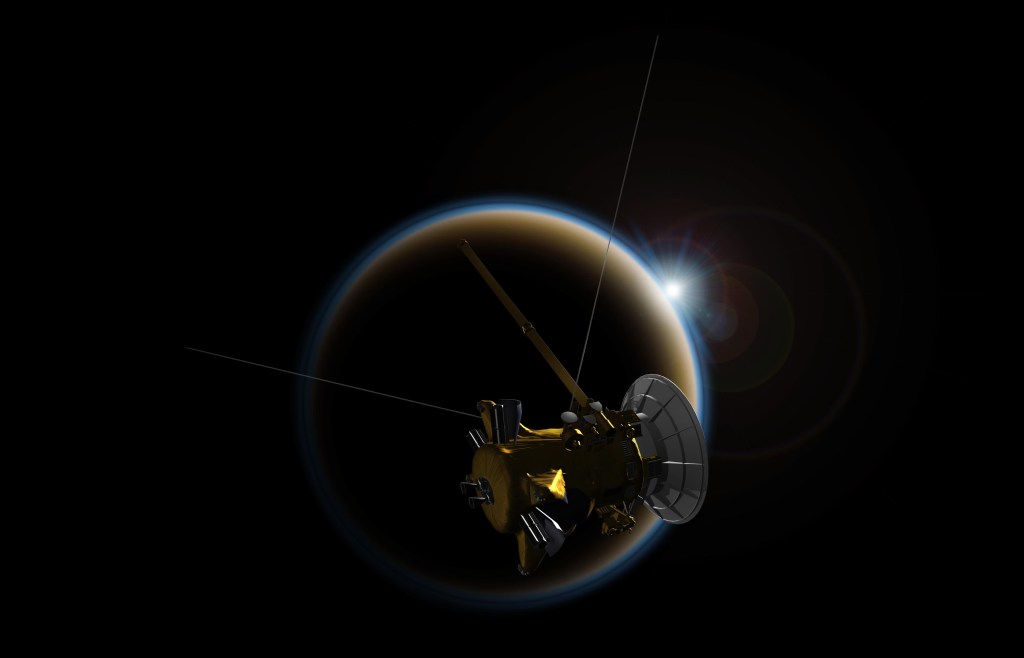

July 23, 1999:

After two decades of telescope optics, mirror, and spacecraft development and testing at Marshall, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory is lifted to orbit aboard space shuttle Columbia’s STS-93 mission. Its “first light” images were obtained a little over a month later, on Aug. 26, revealing previously unseen features of Cassiopeia A, a supernova remnant some 11,000 light-years from Earth. Twenty-five years later, Chandra has delivered nearly 25,000 detailed observations of neutron stars, quasars, supernova remnants, black holes, galaxy clusters, and other highly energetic objects, some as far as 13 billion light-years distant. It has provided tangible evidence of dark matter and dark energy, documented the first electromagnetic events tied to gravitational waves in space, and aided the search for habitable exoplanets. Over the years, Chandra has delivered more than 70 trillion bytes of raw data, with its findings in astronomy and astrophysics documented in more than 11,000 published papers. Marshall has managed the program continuously for NASA, working closely with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which conducts day-to-day Chandra operations and science activities.

More Marshall Decades

Marshall 65

For 65 years, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center has shaped or supported nearly every facet of the nation’s ongoing mission of space exploration and discovery, solving the most complex, technical flight challenges and contributing to science to improve life and protect resources around the world.

Learn More about Marshall 65