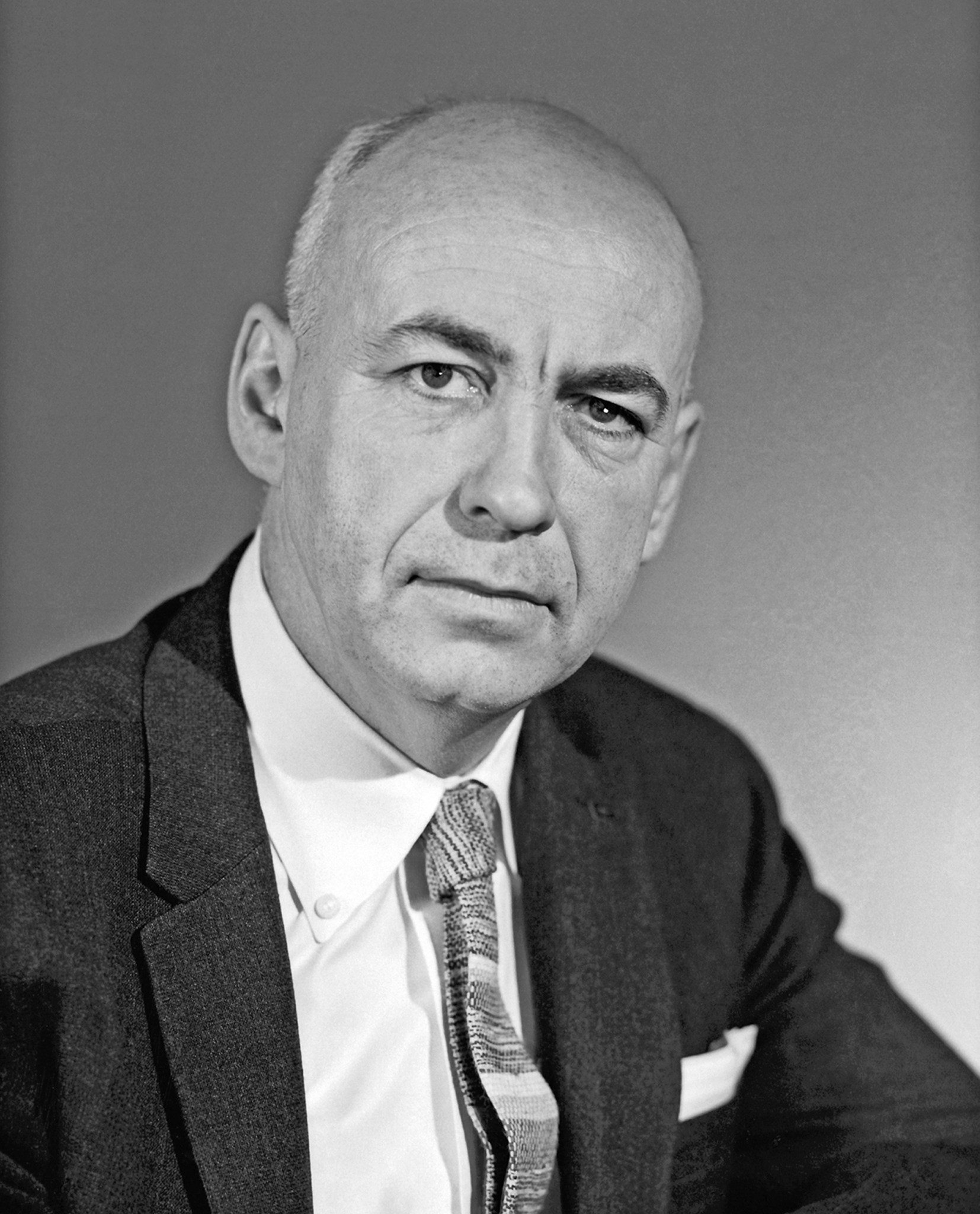

Dr. Robert R. “Bob” Gilruth (1913–2000) conceived and managed pioneering research programs in aeronautics and is considered the father of the U. S. manned space program.

Dr. Gilruth was born in Nashwauk, Minnesota; and attended the University of Minnesota, where he earned a bachelor of science degree in aerospace engineering in 1935, and a master of science degree in 1936. He began his career at the NACA Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in January 1937. He was assigned to a section called Flight Research Maneuvers, and worked for future Langley Director Floyd Thompson and noted researcher Hartley Soule. As a junior engineer, he was assigned to a new project called flying and handling qualities of airplanes, with the objective of deriving quantitative terms to describe what pilots deemed “good” or “bad” flying characteristics, based on their opinions and “seat-of-the-pants” evaluations. Using extensive instrumentation, Gilruth organized and directed tests within his group on over 20 different types of airplanes, including fighters, trainers, and emerging airliners such the venerable DC-3. His ground-breaking research led to an early identification of handling quality problems, and the development of definitive criteria for satisfactory qualities. He published a summary of NACA research on the topic entitled, “Requirements for Satisfactory Flying Qualities of Airplanes,” which became a seminal manual for aircraft designers and operators.

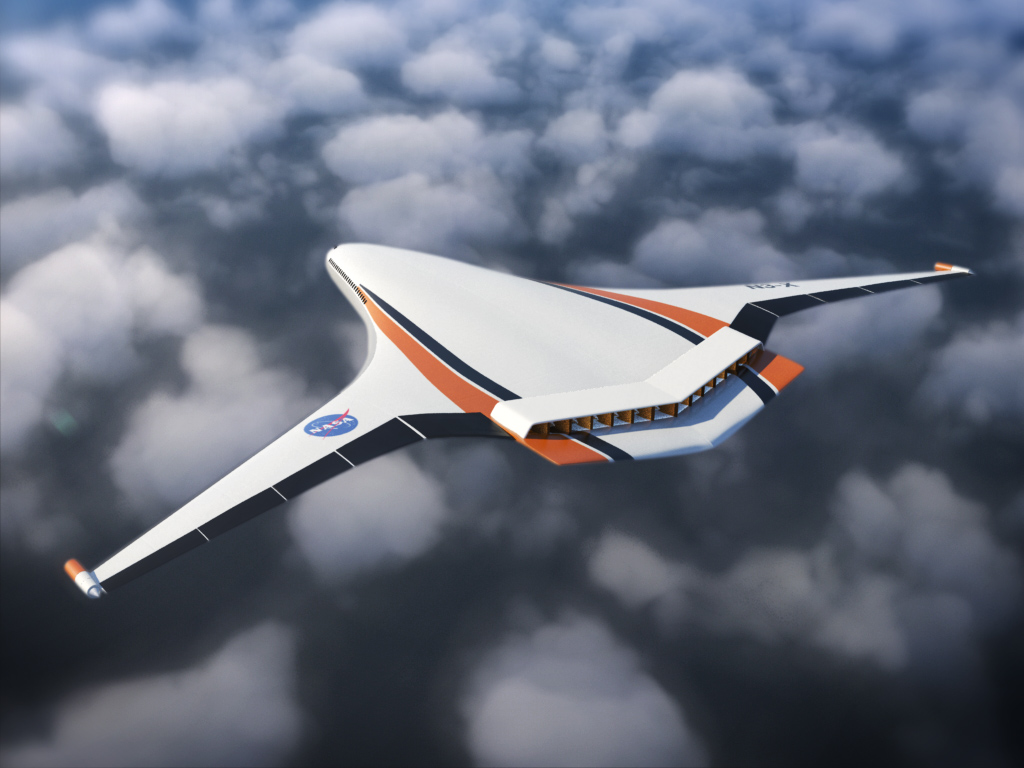

In 1943, Gilruth was promoted to Head of Flight Research Engineering and was in command of all flight-research activities at Langley. During the war years, the combat speed of military fighters had significantly increased and the undesirable effects of compressibility at speeds approaching the speed of sound began to be experienced. Wind tunnels were incapable of measuring aerodynamic data at transonic conditions because of the “choking” phenomenon associated with shock-wave reflections from the tunnel walls. Gilruth personally conceived two research activities to supply critical aerodynamic information in the problem area. One technique was the free-falling body approach using telemetry-equipped models dropped from a high-flying mother aircraft such as the B-29 at 40,000 feet. The second technique involved placing small semi-span models on the wing of full-scale P-51 aircraft. When the P-51 dove to speeds of Mach 0.75, the local flow at specific locations on the wing would accelerate to speeds as high as Mach 1.2, providing a range of desirable test conditions. The model was automatically rotated through a range of attitudes, and a small balance was used to measure the loads. Such tests were extremely valuable, providing an early indication that thin, rather than thick, wings were required for low drag at high speeds. That result shaped the NACA plan for wing thickness of the rocket-powered X-1 research aircraft.

One important concept that Gilruth conceived and demonstrated was the use of an all-moveable horizontal tail to minimize pilot control forces at high speeds. First demonstrated with the XP-42 at Langley, the concept was applied to the X-1 and the F-86, helping to ensure the success of those aircraft. His concept is now used on virtually all high-performance aircraft on an international basis.

In 1945, Dr. Gilruth was assigned the job of organizing a new research group called the Auxiliary Flight Division, with the task of constructing a facility for conducting free-flight experiments with rocket-powered models for investigating high-speed flight. The technique was overwhelmingly supported by industry, which called for an expansion of the NACA capabilities by a factor of three. Under Gilruth’s leadership, Langley formed the NACA Pilotless Aircraft Research Division (PARD) and initiated flight tests at Wallops Island, Virginia — activities that proved to be critical for the transition of the NACA to NASA.

After the Wallops testing had successfully commenced, Gilruth was made Assistant Director at Langley, and turned his attention to the heating and temperature problems associated with high-speed flight, directing related work at Wallops and in the structures area at Langley.

In October 1958, following the shock and aftermath of Sputnik, Dr. Gilruth was selected to be the Director of the Space Task Group at Langley, the organization responsible for the design, development and flight operations of Project Mercury. He was given authority by NASA Headquarters to assign qualified people within the agency to the group. As a part of his responsibilities, he later helped organize the Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Johnson Space Center) in Houston, Texas, and selected its initial, highly-competent workforce capable of performing the many diverse functions required for a program of this magnitude.

He personally advised President John F. Kennedy, during many mutual discussions, that the nation should take on the seemingly impossible task of sending men to the moon – because it was so difficult from a technical perspective.

In 1961, Dr. Gilruth became the Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, with responsibility for the development of spacecraft for manned flight, for flight crew selection and training, and for the conduct of space flight missions. He served in this capacity until January 1972. During his decade-long tenure as MSC Director, Dr. Gilruth managed 25 manned-space flights, including Alan Shepard’s first Mercury flight in May 1961, the first lunar landing by Apollo 11 in July 1969, the dramatic rescue of Apollo 13 in 1970, and the Apollo 15 mission in July 1971.

In January 1972, Dr. Gilruth took on a new position with NASA as Director of Key Personnel Development, reporting to the Deputy Administrator in Washington, D.C. In this capacity, he had responsibility for identifying near- and long-range potential candidates for key jobs in the agency and for creating plans and procedures which would aid in the development of these candidates.

Dr. Gilruth retired from NASA in December 1973 and, in January 1974, was appointed a member of the National Academy of Engineering’s Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board; and was asked to serve as a member of the Houston Chamber of Commerce Energy Task Force.

His awards include the Sylvanus Albert Reed Award from the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Great Living American Award, the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim International Astronautics Award of the International Academy of Astronautics, American Society of Mechanical Engineers Award, the City of New York Medal of Honor, Spirit of St. Louis Medal of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, several NASA Distinguished Service Medals, and the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Service. He also received the prestigious Goddard Memorial Trophy of the National Rocket Club, the Louis W. Hill Space Transportation Award, the Reed Aeronautics Award, and the National Aeronautical Association’s Robert J. Collier Trophy for 1971.

He was awarded honorary doctorate degrees from the University of Minnesota, the Indiana Institute of Technology, George Washington University, Michigan Technological University, and New Mexico State University. Dr. Gilruth became one of the first individuals to be installed in the National Space Hall of Fame.

In addition to NASA websites having extensive resources on Dr. Gilruth’s accomplishments and career, a collection of his papers, notes, records, articles, photographs, awards, degrees, certificates, and artifacts from 1936–1989 is available at the Virginia Tech library.

Dr. Gilruth passed away in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 17, 2000 at the age of 86. He was survived by his wife, Georgene Evans Gilruth, a daughter and a stepson.