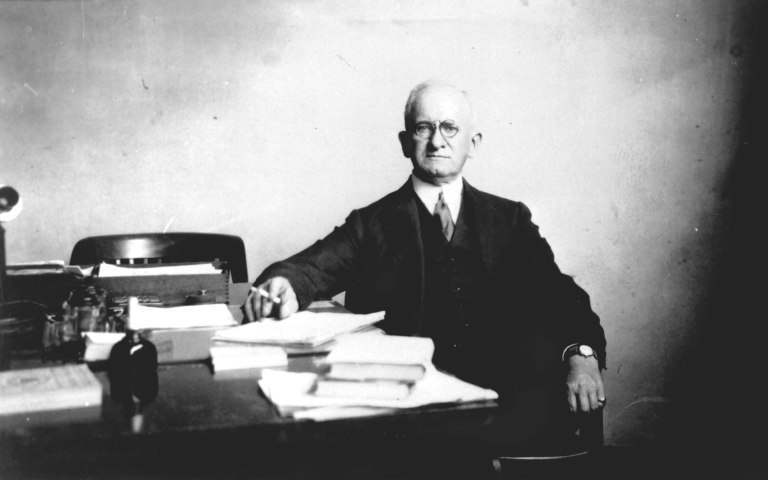

Joseph Sweetman Ames

Founding member of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

Joseph Sweetman Ames was a founding member and the fifth chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the NACA. Ames was one of twelve members appointed to the NACA at its inception in 1915 by President Woodrow Wilson and would, in the words of United States Navy Admiral Ernest J. King, “[lay] the modern foundations for the science of aeronautics.”1 His involvement in the NACA was twofold: his technical background allowed him to contribute significantly to the organization’s research initiatives while his diligence made him a natural choice for an administrative leader as well. NASA’s Ames Research Center is named after Joseph S. Ames.

Ames led the NACA’s Executive Committee beginning in 1920, a role that handled concerns essential for the NACA’s internal operations, such as managing the various aspects of the budget, overseeing the construction of facilities, and deciding upon specific research initiatives. In 1927, Ames served simultaneously as chairman of the Executive Committee in addition to becoming the chairman of the NACA’s Main Committee that year. This position gave him great, lasting influence over research priorities and made him a key player in the NACA’s relationship with other agencies of the federal government. By handpicking and mentoring young, promising engineers and scientists (like Hugh Dryden, who would later head the NACA and serve as NASA’s first deputy administrator), Ames defined the future of the NACA. Under his guidance in these roles, the NACA became a world-renowned, pioneering institution in aeronautics research.

Ames’s interest in aeronautics began with his study of physics. In 1883, he entered the recently founded Johns Hopkins University to pursue an undergraduate degree in the discipline, one that he considered “an entirely new field of investigation and study.”2 His classmates remembered him as a courteous, dignified, and excellent student. Ames remained affiliated with the university long after his undergraduate career. After spending time at the University of Berlin and conducting research at the laboratory of physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, Ames returned to Johns Hopkins in 1887 to earn his doctorate in physics. During this time, he gained a laboratory assistantship overseeing undergraduate students and, soon after, became Director of the Physical Laboratory at the university. Ames joined the Johns Hopkins faculty as an associate professor in 1891 and became a full professor eight years later. During that time, Ames met Mary B. Harrison and they married in 1899. Ames later became the university’s provost in 1926 and its president in 1929.

In addition to his work with the NACA and at Johns Hopkins University, Ames held membership or leadership roles in numerous scientific societies. He became a member of the National Research Council and chairman of its Division of Physical Sciences and its Foreign Service Committee. Over the course of his career, Ames also was a member of the National Aeronautic Association and the American Physical Society. Ames was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an assistant editor of Astro-Physical Journal, associate editor of the American Journal of Science, editor-in-chief of the Scientific Memoir Series, and editor of J. von Fraunhofer’s memoirs on Prismatic and Diffractive Spectra.

Ames expected the NACA to encourage engineering education. He pressed universities to train more aerodynamicists, then structured the NACA to give young engineers on-the-job training. Ames gave the NACA a focused vision that was research-based and championed the work of theorists like Max Munk. The world-class wind tunnels at Langley Aeronautical Laboratory reflected his vision as well as the faith that Congress put in him.

In 1930, Ames accepted the Collier Trophy for 1929 on behalf of the NACA. It was first of many Collier Trophies for the NACA. Ames later received a nomination to the German Academy of Aviation Research, the Deutsche Akademie der Luftfahrtforschung. Ames then considered it an honor, many Americans did, and was surprised to learn about the scale of investment in aeronautical infrastructure in Germany prior to World War Two. Ames therefore urged funding for a second laboratory and expansion of NACA facilities.

By 1937, a stroke had confined him mostly to his home, so he began to step back from his leadership responsibilities with the NACA. Following his resignation in 1939, the NACA issued a resolution stating: “When aeronautical science was struggling to discover its fundamentals, his was the vision that saw the need for novel research facilities and for organized and sustained prosecution of scientific laboratory research. His was the professional courage that led the Committee along new scientific paths to important discoveries and contributions to process that have placed the United States in the forefront of progressive nations in the development of aeronautics.” That same year, the NACA proposed to name its new research facility at Moffett Field, California for him: Ames Aeronautical Laboratory.

Dr. Joseph S. Ames passed away on June 24, 1943. His deep and lasting influence on the direction of aeronautics research facilitated the technological leaps our nation has made in the last century.

[1] King, Ernest J. Letter to Dr. Durand. May 26, 1944. Bibliographical Memoir of Joseph Sweetman Ames (Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 1944).

[2] Henry Crew, Bibliographical Memoir of Joseph Sweetman Ames (Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 1944), 184.