“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

Episode 33 features Dr. Andrea Hanson, International Space Station Exercise Countermeasures Operations Lead within Human Physiology, Performance Protection and Operations Lab. Hanson gives some exercise tips, but more importantly describes what happens to the human body in microgravity, what NASA is doing to about it, and how we can use this knowledge to go deeper into space. This episode was recorded on February 20, 2018.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 33: The Zero-G Workout. I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. So on this podcast, we bring in the experts — NASA scientists, engineers, astronauts — all to let you know the coolest information about what’s going on right here at NASA. So today, we’re talking about how zero g affects the human body and what we can do about it. So working on this very problem is Dr. Andrea Hanson, who’s the International Space Station Exercise Countermeasures Operations Ops Lead. Phew. Oh, there’s more — within Human Physiology, Performance Protection, and Operations Lab. There it is. She’s got a big title and a big job here at the Johnson Space Center. So basically, bad stuff can happen to the human body when astronauts are in space for a long time, and countermeasures are just a way to prevent that stuff from happening. Of course, I had to ask her for some exercise tips, but, more importantly, she described what happens to the human body in zero gravity, what NASA is doing about it, and how we can use this knowledge to go deeper into space. So with no further delay, let’s go light speed and jump right ahead to our talk with Dr. Andrea Hanson.

Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host:Andrea, thanks so much for coming on today to talk about exercise physiology on the Space Station. I was really excited to talk about this specific topic personally because exercise is kind of, I personally like exercising and take a lot of the things that I do in the gym based off of what is being done in space, so thank you again for coming on.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Host:Okay, so one of the big problems that we are facing and the, basically, what you are addressing is microgravity does not agree with the human body when it’s up there for a long time, right? So what’s going on there?

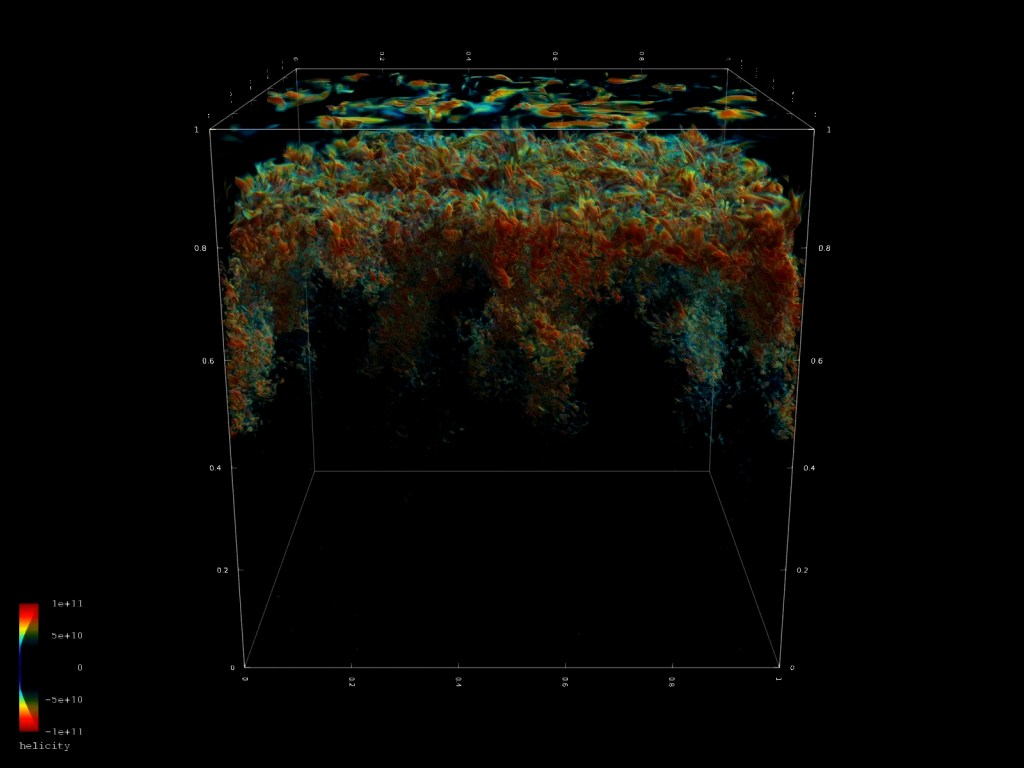

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. So the body responds pretty immediately to living in the microgravity environment through going through a series of adaptations to adapt to this new sensation of free float. And those adaptations happen pretty immediately. Upon getting into outer space, that you experience fluid shifts, and that might cause, like, a stuffy head sensation and maybe even some slight motion sickness in the first day or two. But the spine starts to elongate, and, immediately, all those little mechanosensors that tell your body it needs to keep strong to even stand up straight, go up and down stairs, sit in a chair, and stand up again, they start to turn off, and that’s where we start to see the muscle strength losses and bone atrophy that we know our astronauts can experience, even at as soon as two weeks in space.

Host:Wow. Okay, so some of this is happening immediately. Some of this, as soon as you get up there, all of these, like, what’s happening immediately, and then what is gradually happening over time?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. So immediately, astronauts will start to experience those fluid shifts.

Host:Oh, that’s the first thing. Okay. And then, so then, the, I think the equilibrium, basically, your equilibrium is one of the first thing that shuts off too, right?

Andrea Hanson: It sure is.

Host:Yeah.

Andrea Hanson: And you lose that sense of balance because, well, there’s nowhere to fall in microgravity. [laughter]

Host:Okay, so then, basically, what, how is microgravity, basically, how, what is causing this problem, this, the reason why you are losing muscle and bones? Is it a little bit because you’re not really using it as much?

Andrea Hanson: That’s exactly it. It’s that principle of, you don’t use it, you lose it. And you know, being an enthusiast at the gym, [laughs] that if you stop a regular exercise program even for a week or two, it can get, be really hard to get back into the gym.

Host:Oh, that is the worst part about going to the gym is, if you take that break, it’s really hard to get back into it.

Andrea Hanson: It sure is. And not only is it hard to get back into it, but you do notice some immediate losses in strength and maybe aerobic fitness if you do take those breaks. So it’s kind of the same thing. When you go into outer space, you just don’t have those regular stressors on the body that you do living in the one-g environment. And again, the body responds to that really quickly.

Host:Absolutely. And basically, the longer you’re in space, the more it affects you, right?

Andrea Hanson: It sure does. And so we have to develop a series of what we call countermeasures to fight against this sensation of not needing to maintain muscle strength or bone health to make sure that when our astronauts come back to Earth, they’re in good shape to resume normal daily life again.

Host:And that’s basically where you come in, right? This is the countermeasures that you’re talking about. We have this issue. There is this idea that your muscles are degrading, your bones are not as healthy, right, you’re starting to see that loss within those, that parts of your body, so a countermeasure is basically a way to prevent that. So what are some of the countermeasures we’re seeing?

Andrea Hanson: Great question. We use exercise as kind of the foundational countermeasure to a lot of those adaptations that the body goes through. And right now, we have a really robust gym on the Space Station. We’re pretty lucky. We have a treadmill. We have a exercise bike. And we have a really neat device we call the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device, or the ARED, and that’s for strength training.

Host:Okay, so how does that work? How do you lift weights in a microgravity environment?

Andrea Hanson: [laughs] Yeah, that, it’s almost a trick question, isn’t it? [laughter] Because if you were to bring a 50-pound dumbbell up into space, of course, it wouldn’t weight anything.

Host:Be so easy.

Andrea Hanson: [laughs] It’d be so easy. It’d be too easy, and it wouldn’t stress the body in a meaningful way to help you retain that strength.

Host:Yeah.

Andrea Hanson: So essentially, the engineers that developed this piece of equipment had to get really creative.

Host:Okay, so then how does it work? How does ARED work?

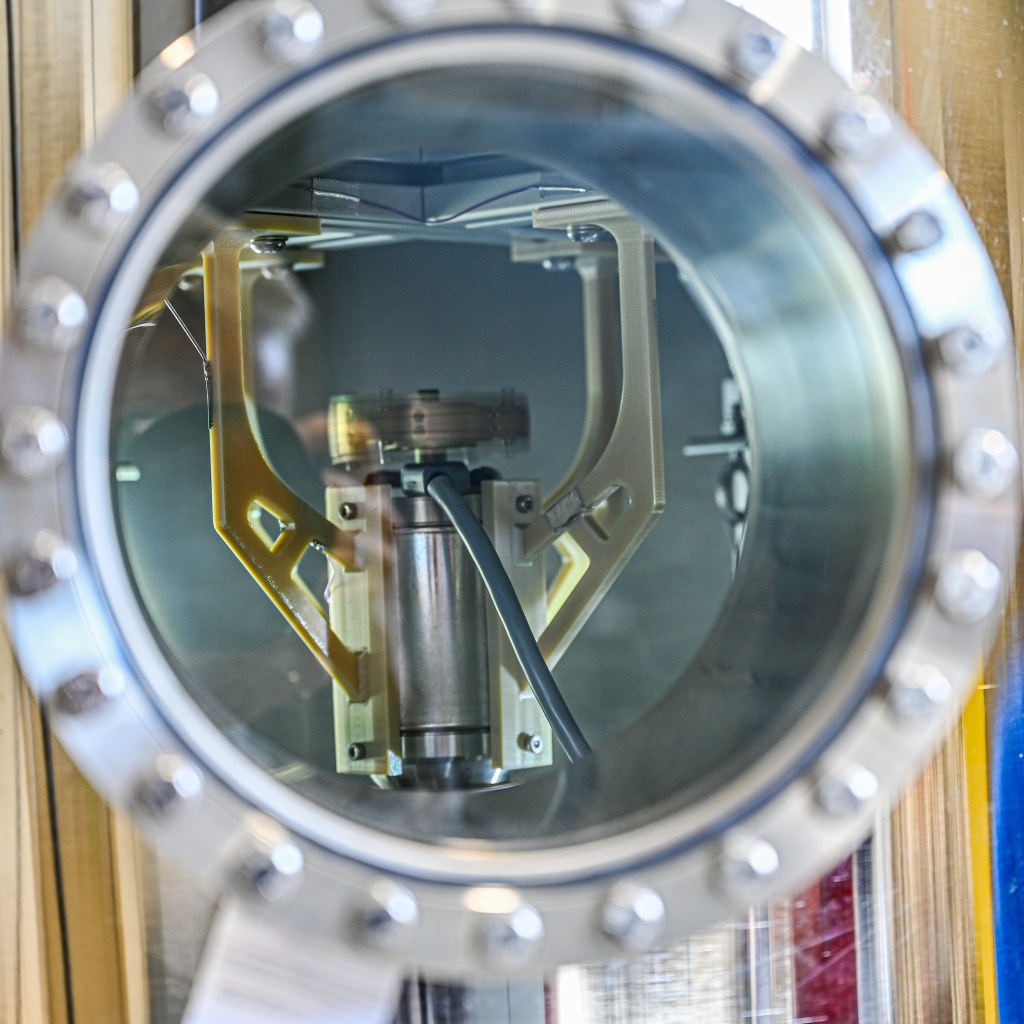

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. ARED’s a really sophisticated piece of exercise equipment. Unlike a lot of the free weights you have here in the gym, we had to design a way to impart a mechanical influence on the body, and we did that through a real creative mechanism using vacuum cylinders and kind of a cantilever device. You can think of it as a teeter-totter that moves along a fulcrum so that you can adjust the load from zero up to 600 pounds of resistance load.

Host:Okay, so it’s not just laying on the side of the Space Station. Now, there’s this sort of balance where, if you’re pushing off something, I’m imagining if you have like a, let’s say a bar, like a bench press bar, and then you have the actual bench that you’re laying on, you have this, basically, when you’re pushing up, that bar is going up, but then you’re also kind of going the other way because it’s on this fulcrum, right?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. I think you’ve got this visualization pretty accurate.

Host:Okay.

Andrea Hanson: Essentially, when you’re exercising on ARED, you’re kind of in a clamshell or in between a clothespin where you’re pushing off against a platform and up against an exercise bar. So whether you’re standing and you have that exercise bar on your shoulders or you’ve installed the bench attachment and you can do bench presses, ARED allows one to conduct over 45 different types of exercises.

Host:All right. So that means you can kind of adjust it. You can attach, I guess, I don’t know, pulleys or do more of a squat kind of setup?

Andrea Hanson: Exactly that.

Host:Okay.

Andrea Hanson: ARED can be used for those full functional strength-training exercises or more of those targeted, like, bicep curls or ab/adduction type exercises.

Host:Okay, so how long does it take to kind of switch it up, then?

Andrea Hanson: It is pretty easy to manipulate the hardware itself, to change it from, say, a squat exercise, and just a couple minutes to pull out the bench, click that into place, and then do something like a bench press exercises. So it happens pretty rapidly.

Host:Nice. How long during the day do they actually take out for exercise?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. And this is where it really highlights the importance of exercise. Astronauts are scheduled two-and-a-half hours, six days a week for exercise time.

Host:All right. That’s a lot.

Andrea Hanson: And that’s pretty significant when you consider crew time is one of our most valuable commodities. Now, they’re not, you know, breathing hard that entire two-and-a-half hours, six days a week, but what that allows them is time to get the ARED into the configuration they need it to and go through a full, you know, good strength-training exercise program every day and then also get some cardio fitness in too, whether they’re spending that on the treadmill or the exercise bike. Collectively, they have that time to, you know, get changed into their workout gear, do their exercises, and then a little time to recover and clean up as well.

Host:Okay, so that two-and-a-half hours is not just, all right, go, and then run for two-and-a-half hours, or do, like, you know, a resistive exercise for two-and-a-half hours. This is including the entire thing — setup, changing, getting the ARED situated in different configurations, all of the above. Two-and-a-half hours, that’s your time.

Andrea Hanson: That’s right.

Host:Okay. So you, we kind of touched on it a little bit is the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device is one component. It’s got the vacuum cylinders. Simulates weight lifting. You need this resistive exercise to prevent, is it muscle and bone loss? Is that what you’re doing on that machine?

Andrea Hanson: It sure is. Yeah, each of the exercise devices kind of has its own unique training behind it, and so the ARED, the strength training, of course, is good for muscles and bone health, bone quality. Treadmill, you get that important mechanical stimulus every step of the way, so that’s great for bones and cardiovascular fitness. And of course, the cycle ergometer — we call it the CVIS, the Cycle Ergometer with Vibration Isolation System — is really good for cardiovascular training as well.

Host:Okay, so you get a little bit of that impact from the treadmill and the cardio stuff from the stationary bicycle. Excellent. So if you’re running on the treadmill, how do you stay on?

Andrea Hanson: [laughter] That is another great question. Yeah, we need a special harness, actually, to pull the astronauts down to the surface of the treadmill. So we have, we’ve created a harness kind of copying the technique or design of a backpacker’s harness, where you can adjust the loads from the shoulders to the hip, and then that is all held down to the surface of the treadmill through a series of bungee attachments. And so you can actually adjust the load. Very ideally, we would create a one-g environment and have them run with the full load that their body would be imparting during a running protocol. However, you can imagine that can get pretty uncomfortable when all of that load is being, is forcing you down through the shoulders and the hips, even if you can adjust that to distribute the load. So typically, astronauts are running between 70 to even 90% of their fully body weight towards the end of a mission, and some of them do get up and recreate that full body weight loading on the treadmill. But it’s a balance between comfort and the ability to get a really good workout in.

Host:I see. So that, basically, getting it down below one g, getting to that 70% whatever, just makes the harness a little bit more comfortable–

Andrea Hanson: That’s right.

Host:Because ultimately, you have this impact sensation where you’re going up and down. You got the harness on you. So yeah, I could see how that can bother you.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah.

Host:Is it made out of metal, the harness?

Andrea Hanson: No. The harness itself is actually fairly comfortable. It has some–

Host:Oh, okay.

Andrea Hanson: Nice padding on it. It has some lumbar support. It has padding around the hips where you might experience some of those hot spots. And it’s quite adjustable. But there are, we do use metal clips that attach to the bungee, to the harness, and then, ultimately, to the treadmill.

Host:I see. What kind of exercises are they doing on the treadmill? Are they basically doing, like, long jogs, or are they maybe doing high-intensity kind of sprinting? Are they doing something a little bit more I guess intense but interval training?

Andrea Hanson: Another great question, and it’s really a combination of both of those.

Host:Okay.

Andrea Hanson: I think for anyone engaging in a really regular exercise program, having the variety in exercise prescriptions is really important and really key to maintaining that motivation to come back and do it again every day. And so you will see the astronauts running for long durations at a time. We’ve had a few astronauts who’ve even conducted marathons in space–

Host:That’s right.

Andrea Hanson: [laughs] Which is pretty great. Suni Williams, of course, has run, she ran the Boston Marathon. Tim Peake recently run the, ran the London Marathon up there. And so those were, of course, those long, continuous runs. But more regularly, we are seeing the astronauts engaging in those high-intensity training protocols. And so on the treadmill, that might mean four-minute intervals with four-minute breaks or six 30-second sprint intervals with breaks in between as well. And that really stresses the heart and gets you up in that 90% maximum heart rate range, which is really effective at maintaining cardiovascular health, even during those short durations of exercise.

Host:Is it proven to be more, or more or less effective, or is there a reason to do this interval sort of training?

Andrea Hanson: There is a really good reason, especially in space, and that’s a time-saving–

Host:Oh, I see.

Andrea Hanson: Trade, for sure. And so again, it’s advantageous to conduct both continuous running and that interval training because it stresses the body in different ways, all of which are really important, but it is, has been really effective to engage in these high-intensity protocols. We find that it can save a little bit of time in your day-to-day exercise [laughs] time and still able to maintain health.

Host:So you can kind of shave off that two-and-a-half hours, then, if you were doing the interval training, the high-intensity kind of exercises, then, right?

Andrea Hanson: Ultimately, yeah. That, and that’s kind of what we’re looking at, especially for these extended, long-duration missions, where, again, it can be stressing on the body to engage in long-duration exercise every single day. So we’re looking at all of those trades that can be made to really offer the crew a good mix of effective workouts, but something that’s going to make them, again, want to stay motivated and adhere to their exercise protocol as well.

Host:So are you saying that it is sustainable? Is it, can an astronaut actually keep up with high-intensity interval exercise every day?

Andrea Hanson: [laughs] Well, they certainly can keep up with high-intensity exercise. And again, it’s not every day, but it’s, say, three days a week–

Host:Oh, I see.

Andrea Hanson: Instead of the full six days a week. It’s certainly sustainable. And we’ve conducted a couple of studies in the last couple of years, both here on the ground using the bed rest analog and repeated that in space to demonstrate that it was tolerable to maintain these higher-intensity exercise protocols.

Host:So you talked a little bit about variety and how that kind of helps with switching it up, getting the body to maximize its performance by having I guess the, by switching up the routines that you do. Is there a consistent schedule for exercise every day? Like, do they do it the same time? Do they do the same routine? Is there like a weekly thing?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. Well, getting that full two-and-a-half hours of time in is pretty tricky for the schedulers.

Host:Oh, yeah.

Andrea Hanson: One really interesting thing we know about exercise is that the body actually needs rest periods. And so it’s fairly important to separate your strength training workouts from your aerobic workouts to give the body the rest it needs to, so you can stimulate it all over again, and it really optimizes, especially for bone health, the ability for your bones to respond to that secondary workout for the day. So when possible, we do try to break up those workouts. But of course, when it comes to going to the gym, [laughs] there’s also a matter of efficiency in getting it all in at once. So it’s a trade, and the ops teams and schedulers work really hard to find that balance that works both for the crew and for the daily schedule.

Host:Yeah, that’s something I actually try to do is basically I’ve learned that you can’t, you shouldn’t really do the same resistive exercise, like, two days in a row. So if you’re going to do, like, bicep curls, the next day, you should probably do something else. Maybe switch it, so a leg day, or maybe switch it to a cardio day. But basically, doing it that two days in the row, you’re right, does not provide the body the sort of recovery time it needs.

Andrea Hanson: Exactly. And the astronauts are really lucky to work with essentially personal trainers. We call them the astronaut strength, conditioning, and rehabilitation specialists, or their ASCRs, who are taking a really close look at those exercise protocols and making sure that they’re optimizing them day in and day out for the astronauts.

Host:Okay. So how often do the ASCRs work with the astronauts, then? Is this a daily thing?

Andrea Hanson: It’s a daily thing.

Host:Oh, wow.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. They send up protocols and prescriptions every day. They receive feedback. They can sometimes have a conference with them. They check in on a regular basis to make sure that crew are comfortable with the exercise hardware, if they have any concerns. Maybe they know that they have a really packed schedule coming up for a couple of days, and they need to make some trades in their exercise workout to make sure that they have the full mental aptitude and are prepared to take on the otherwise stressful schedule and balance that with use of exercise.

Host:So it sounds like the, basically, it’s kind of personalized. It sounds like it kind of varies between crew member, that maybe this crew member may need a little bit more of X, Y, and Z, whereas this one needs a little bit more A, B, C.

Andrea Hanson: That’s exactly it. It’s a very individualized, and it’s important that those trainers know their crew members really well so that they can have a real honest conversation over how to maximize their time working out.

Host:So do the ASCRs, these trainers, work with the astronauts before and after spaceflight to kind of understand them?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah, they sure do. They spend a year or more training and helping each crew member prepare for their flight, work with them day in and day out when they’re on Space Station, and then spend some good time with them once they get back to Earth to make sure that they’re healthy, and fit, and able to, again, jump into their regular ground-based exercise protocols or just that day-to-day activity, like riding a bike, playing with their kids, [laughs] going to the grocery store, and making sure they’re not at risk due to muscle fatigue or bone weakness.

Host:That’s right, because there’s a recovery period whenever they land, right? It’s not like, because your, again, your body is now adjusting to the regular Earth gravity, and so you got to go through this period. But from what I understand, the astronauts are right back into it, right? They are starting to exercise almost a couple days or maybe even the same day. What’s it look like after they land?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. Just like when you get into space, your body responds very rapidly to that microgravity environment, when you come back to Earth, it takes a couple of days for your body to get used to that again.

Host:Yeah.

Andrea Hanson: And that balance component we talked about early on, that’s one of the senses that is disturbed for a little longer than the others. So even if we did a really great job of implementing exercise protocols in space, they maintain their muscle strength, they maintain their bone quality, upon coming back, we still have to be careful that we’re engaging them in the regular daily activity in a very metered way so that we can make sure that they’re used to, that they have their balance back and that they do feel comfortable with the strength levels they have to resume that normal daily routine.

ost:What are you seeing with the astronauts whenever they come back? How, what’s the length of time until they’re, I guess, quote, unquote, “back to normal”?

Andrea Hanson: Well, that’s a really good question, and I think that the answer varies for the different systems of the body that you want to talk about. But there, of course, most crew are able to get up and walk around on their own within a day or two after landing. And they are getting back to regular exercise programs, at least. Muscle strength, if there were losses that were experienced during their spaceflight mission, can be returned to baseline values within two to six months, depending on, again, the individual and how they adapted both to space and coming back to Earth. But when we look at those long-term turnover systems like our skeleton, those can take a little longer to recover. And of course, you have other factors playing into this that include age, normal activity levels, and, again, the stressors of this schedule that astronauts experience upon coming back and needing to fulfill a lot of those post-mission responsibilities.

Host:All right. Because they basically have this recovery time, but, also, they need to get back to work, right? So–

Andrea Hanson: Exactly. They do get right back to work. They have a lot of debriefs. They have, they capture all those lessons learned from their space mission. They do a lot of public speaking and sharing their experience, both internally and externally. And they do a lot of travel [laughs] right after returns. And of course, they, it’s important for them to spend time with their families upon coming back as well. So their schedules remained stressed for quite a while after their mission.

Host:Wow. So it’s kind of, they’re in high demand, you can say, because they are a recently-landed crew member, which means that they are in, they want to go, and people want to hear them speak and go out to different engagement events, but then, also, they got to travel for work reasons too, balancing the time with the family, balancing the recovery time. There’s a lot that’s going on in that after flight time.

Andrea Hanson: Absolutely.

Host:Are you finding that, like you said, there are, you are monitoring what they’re doing? You’re basically, the ASCRs, the trainers, are monitoring them day to day to see how they’re performing. Is there, are you tracking to see which types of exercises may be more effective than others? For example, maybe astronauts that are putting a little bit more heavier loads on ARED and really pushing themselves for that strength training, maybe they see a little bit more recovery than others.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah, tracking exercise data is something that we take very seriously, and we actually deliver reports every two weeks both to the flight docs and to the ASCRs so that they can track the progress of the exercise prescriptions in a way where we can take a step back and look at progression over time instead of being wrapped up in that day-to-day care. And so we get a lot of great data down from Space Station from the treadmill, for example. We know at which speeds they’re running. We know what load they’re pulling themselves down to that surface with. And we get heart rate data. So we can look at the intensity of their exercise. Same with the cycle ergometer. We’re looking at workloads, and heart rate on there, and distance traveled, or simulated traveled, of course. [laughs] And on ARED, right now, we are tracking manually how, what loads are being dialed in, and how many repetitions, and how many sets are being performed by each crew member. The ARED was originally designed with a force platform and load cells that was going to record the loads dialed in and the ground reaction forces experienced during exercise and automatically count the repetitions and record the sets of exercise. We had a mechanical failure when, shortly after ARED was installed.

Host:Oh no.

Andrea Hanson: And so we’ve looked a long time for interim load monitoring solutions. And that’s where we introduced a study called the force shoes, where we looked at a pair of instrumented sandals, essentially, that would help record the exercise loads. And what that did was give us confidence that the hardware was working consistently and actually delivering the load that was dialed in and reported by the astronauts. So that was a big confidence booster that our exercise hardware was in good working order.

Host:Force shoes was one of the things you actually worked on, wasn’t it?

Andrea Hanson: Yes, it was.

Host:Very cool. So basically, it was kind of a way to measure and just make sure that the ARED was, indeed, giving the load that you were dialing in. It was kind of this check and balance but also did a little bit of reporting too? Like, was it, were you able to record the measurements, I guess, the exercise?

Andrea Hanson: Yep. The load cells on the instrumented shoes allowed us to record that data. We could look at ground reaction forces that allowed us to analyze how weights and our loads were being distributed underfoot. You know, during a regular exercise or strength-training program, you’re always being told to push through the heels. Push through the heels. And that’s–

Host:Yeah.

Andrea Hanson: Exactly the type of form that we’re looking to see the astronauts carry out in flight as well. So we could take a real close look at that data and help them out with a little instruction, if necessary, or just confirm that they were doing it right.

Host:Okay, cool. So it has this feedback–

Andrea Hanson: Yep.

Host:Sort of the technique feedback because making sure, and you’re absolutely right. Definitely, whenever you’re doing squats, it’s definitely on the heels that you want to have that kind of load. So if you’re putting a little bit more pressure on I guess the side, or the front, or whatever, the force shoes can tell you that, and then you can say, hey, you need to put a little bit more on that, because, ultimately, the good technique is what’s going to get you the best results.

Andrea Hanson: That’s right. And that’s why it was really important for us to have that force plate installed [inaudible]. And just recently, we were able to turn it back on. So we’re really excited to compare the data from the force shoes to the force plate. And again, it will give us that confidence that it’s in good working order or that we can only utilize data from one load sensor or the other.

Host:So we’ve been doing exercise on the Space Station for quite some time now and have a lot of different astronauts that have gone on, done a lot of different exercises, and we have all of this data. Can we say that we have enough data to say, yes, we are ready to go further out into space for longer and longer missions, even beyond the normal six-month increment that we’re seeing on the Space Station? In fact, we have a little bit of data from the one-year mission, right?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah, we sure do. We have a very rich database of exercise data. What’s really interesting about that is on Space Station, we’ve been really lucky to, again, have real capable exercise hardware and a large variety of exercise hardware. So we’ve always had a treadmill. We’ve had that cycle ergometer and that really robust strength-training device. When we think about going on to exploration missions, the size of our vehicle is going to be much smaller than the International Space Station is today.

Host:That’s right.

Andrea Hanson: And so that’s challenged us to come up with new hardware design that’s smaller footprint, lower volume, lower power, and we’re right now working on designing and testing that exercise hardware to be able to compare how similar it is to the hardware available on Space Station and where we might need to introduce additional components or features in that hardware to make sure that the astronauts going to Mars do, are able to get a really good workout in.

Host:You know, one of the benefits of the Space Station is how big it is, right? It’s like the size of I guess a five-bedroom house or something. So you can easily fit three different exercise equipment, and actually, it’s, there’s more on there, right? You’ve got the ARED. You’ve got the T2 treadmill, the COLBERT. And you also have the CEVIS stationary bicycle. But then, you have the, some Russian equipment as well.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. We’re really lucky that the, on the Russian module, they have their own exercise hardware, so we don’t have to share time on all of the devices. That would be really a scheduling nightmare. So they do have their own treadmill, their own exercise bike, and then we share the use of ARED.

Host:You know, that’s actually one component that I kind of skipped over was you have six astronauts onboard the Space Station that are working out two-and-a-half hours a day. Where do they find the time?

Andrea Hanson: [laughs] Exactly. It is–

Host:They have to rotate on the same machines.

Andrea Hanson: They sure do. And that is a huge challenger for the ground-based schedulers to make sure that everyone’s getting a fair amount of time on all of the hardware as well. And pretty soon, we’re going to be increasing the number of crew from six up to seven and, at some points, even 11 different crew members with our visiting vehicles. So there’ll be short durations of time with many crew members aboard. And we’re right now looking at what those schedules need to look like and what adjustments need to be made to be sure that everyone gets the exercise time they need.

Host:You know, I’m thinking about the constant use of this, especially if you’re getting up to that number of crew members. The constant use of these machines, do they require a fair bit of maintenance?

Andrea Hanson: They have, all have a regular maintenance schedule. Every mechanical device is essentially designed to fail at some point. And so that’s why it’s really important that we’re monitoring the health of the hardware on a regular basis. We’re looking at cycle counts. We’re looking at hours of powered on time. And we stick to a really strict maintenance schedule to make sure that the crew experience as little downtime as possible due to mechanical failures. So we kind of anticipate when those are going to happen and make sure we replace the pieces that need to to ensure that they can stay up and running.

Host:I guess taking that consideration to I guess going back to our talk before about these vehicles that are going to go further out and perhaps even, like, especially Orion, going to be smaller, right? So now, you don’t have the room for all of this exercise equipment. That’s initially where I was going. But you have the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device, which is actually pretty decently sized, right?

Andrea Hanson: Right.

Host:If you put it in Orion, it would probably take up most of Orion. [laughs] So you can’t really do that. Or actually, would it even fit?

Andrea Hanson: Yeah, I don’t think ARED would even fit. It is a very large device. It’s very heavy and very capable. I think everyone would love to see ARED being sent to Mars, or at least a derivative of it. And that’s really what we’re trying to do — taking all those lessons learned from that hardware design and the stresses that has been put on that hardware to make sure that the devices being designed for those smaller exploration vehicles are going to be able to stand up to the stresses and the continuous use that we expect that they will have. And so right now, while we’re being challenged to kind of design, have one piece of hardware that’s going to be a cross-training, both aerobic and strength-training device, we know that multimodal exercise is important, which is why we have the cycle, the treadmill, and the strength-training device today. But also, that robustness and the ability to make sure that we have operational hardware available is almost as important as the functionality of any one device.

Host:That’s right. And you kind of have to have a certain set of redundancy too, right, because you can’t , I guess if you’re having all of these crew members going on a long mission with one machine, gosh, what if that machine breaks, right? You’re going to have to–

Andrea Hanson: What if it broke?

Host:Yeah, so are you talking about having multiple machines?

Andrea Hanson: We’re evaluating that right now–

Host:Yeah.

Andrea Hanson: To be sure that we are providing whatever functional exercise system’s going to be required to maintain health during those three-year missions.

Host:Okay, I see. So actually, selfishly, one of the things that I wanted to ask you was, since, you know, like I said, we were talking about, there’s so many astronauts on the Space Station and have exercised this number of times. You have these sample size. And you’ve seen all the different types of exercise and how they are performing. Do you have certain tips and tricks that you’ve taken from the astronauts and taken into your own life for your own exercise?

Andrea Hanson: Well, absolutely. I mean, the astronaut core, they’re a very motivated bunch, and it’s really impressive to see how responsible they are for upkeeping their own physical fitness and health. And so it’s really great to watch them as they train pre mission to see how they’re targeting their fitness goals to make sure that they’re ready for that flight, that launch, and that long stay in space. And because I am privileged to take a look at the exercise data that comes down and help write those medical reports, I know firsthand how hard they really are working. So it’s pretty impressive that they’re able to adhere to and maintain those high-intensity exercise protocols over those six-month missions. And in one case, even one, a whole year of pretty intense went on. And so it’s pretty impressive to me to see how they take it very seriously and how they do try to hit those fitness goals as they’re prescribed by their trainers. And so one thing I’ve taken away is I do hire a trainer to [laughs] help me work out so that–

Host:Oh, wow.

Andrea Hanson: I’m making sure that I’m pushing myself and somebody’s there to help keep me motivated along the way.

Host:That’s right. That constant motivation is so key.

Andrea Hanson: It is.

Host:So key to the success because you’re, like I was saying before, you know, it’s so easy to drop off and stop exercising for a little bit just because of whatever excuse you can come up with. But if you have that sort of accountability and someone tracking you and keeping you on the track to whatever goal it may be, whether it be muscle gaining, or weight loss, or whatever, you know, you’re going towards that goal. That makes so much sense.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. And I think with the astronauts, they realize they’re also accountable to each other. They need to be there and ready to support each other if it’s during an EVA, an extravehicular activity, or helping out with something really important inside the Station. Even if it’s helping each other out upon landing, they know that they all need to be in top physical condition to enable mission success overall.

Host:Okay. So actually, I wanted to kind of go back and talk more about, are you an exercise physiologist, or I think you have an engineering background.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. Actually, my background is in engineering. I studied both chemical and aerospace engineering but really focused on the bioastronautics and microgravity sciences aspect of the aerospace engineering discipline, which meant that I focus on the human in the loop rather than the vehicle surrounding them. My personal research interests have focused on maintaining musculoskeletal health, whether it’s the muscle physiology or the bone health — really understanding what those mechanostats, those mechanical-sensing cells in both muscle and bone, what they need to stimulate and make sure that we’re maintaining proper health for our bodies. And it was understanding at that cellular level the sensitivities to the mechanical inputs that the body experiences and how that’s important for maintaining health when you otherwise take away the gravitational vector that help me to think more critically about the importance of exercise hardware design and the way that we measure exercise data and then analyze that to correlate to how the exercise protocols we’re giving the astronauts help to maintain health.

Host:Okay, so that goes back to that force shoes thing, right? That was–

Andrea Hanson: Exactly.

Host:One of the things you worked on because it’s this device that literally helps exactly what you’re saying, that understands the body and how it’s responding the exercise and can improve that.

Andrea Hanson: Yeah. I think it’s no secret that exercise works — [laughs] on the ground and in space. But until we have the data and can break down those numbers to say exactly how it’s pinpointing loads on individual joints and activating muscles in a meaningful muscle recruitment pattern, that we’re truly going to understand why exercise is so effective in space.

Host:It’s so true. And I know just from exercising myself, there’s a component beyond just the physiological, beyond just your muscles and bones, that’s really helpful just basically maximizing the performance of your body. But basically, also, understanding the mental and emotional aspects that exercise bring you. Is that something that’s being investigation on the Space Station?

Andrea Hanson: Absolutely. I think use of exercise time as an emotional reprieve and break from that high-stress schedule has been heavily recognized and another reason that we’re able to protect that two-and-a-half hours of time, six days a week and label it as exercise time. It’s a good chance for the crew to not only kind of focus on their own individual health, but kind of take a break from the rest of that real demanding schedule.

Host:I see. Yeah, I guess, yeah, it’s kind of their — you, I guess you wouldn’t call it personal time, but it is sort of a break from the mental stresses of doing hundreds of experiments over the course of your six-month increment.

Andrea Hanson: That’s right.

Host:Okay. So actually, I wanted to end with one thing that we touched on earlier, which was this idea of recovering after a spaceflight. And we talked about how your muscles and bones, you have this period of recovery, and even your balance and how that’s going to recover once you get back, it takes some time for your body to get adjusted. I’m thinking about landing on, beyond Earth, right. I’m talking about landing on Mars. If you’re landing on Mars, what are we doing to make sure the body will be able to perform once we land on another planetary body and you’re undergoing the same things where your body needs to have this adjustment period?

Andrea Hanson: That is such an important question and really important to recognize today when the crew lands back on Earth, they have an entire welcome wagon here ready to help them up and out of the capsule, and get them to the medical support tents, and make sure that they are safely on their way home. When we land on the surface of Mars, that welcome wagon will not be available. So what we’re working on today is creating a real autonomous exercise system so that we can provide the crew with really individualized and meaningful fitness goals. And how do we do that? Well, we took a look and evaluated, what kinds of tasks are they going to have to do once they land on the surface of Mars? And some of those are pretty obvious. They’re going to have to get up and out of the capsule [laughs] and safely to that prepositioned habitat or equipment that will help them set up base. They’re going to have to walk around on this unfamiliar and probably uneven terrain and be careful not to experience unnecessary trips and falls along the way. And if they do, they might have to help an incapacitated crew member.

So these are the types of fitness goals that we’re looking at in being able to, one, provide a real targeted training number so that they can perform these types of tasks once they get to the surface, and then we’re going back and asking ourselves, did we design the exercise hardware to help them meet these functional fitness goals?

Host:All right. So a lot of work being done, of course, because this is a, this is one of the largest considerations for landing on Mars is once you land on there, can you perform? Will you be able to accomplish what you want to accomplish? Absolutely. Well, Andrea, thank you so much for coming on and kind of describing this exercise in space. And, I mean, I’m taking some of the lessons learned from the astronauts and just the idea of, we didn’t touch on it so much, but the idea of resistive and aerobic exercise, right. The idea of mixing it up, making sure you have the resistive exercise on the ARED and the aerobic with the stationary bicycle and the treadmill, mixing it up, and basically staying consistent, right. Now, I’m consider a personal trainer. [laughs] I don’t know.

Andrea Hanson: There you go. That might be the key to your success. [laughs]

Host:All right. Well, Andrea, thanks again for coming on.

Andrea Hanson: Thanks so much for having me.

[ Music ]

Host:Hey, thanks for sticking around. So today, we talked with Dr. Andrea Hanson about exercise in space and how that’s going to help us go further and further into the cosmos. If you want to know more about how the astronauts are exercising in space, go to NASA.gov/ISS, or you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, the International Space Station accounts, to see what they’re doing right now. Otherwise, you, there are plenty of other NASA podcasts that you can tune in to. We have Gravity Assist that Dr. Jim Green talks about the planets in our solar system and some, and beyond, ultimately, having great talks with some cool people like Andy Weir just recently. And also, we have NASA in Silicon Valley out at Ames, who helps out with a lot of the stuff on the International Space Station, is doing some cool stuff with Twitch and going live on TV to talk about cool things like playing video games, and how video games sort of help us to understand components of space, and how they inspire others to understand components of space. Very cool stuff that they’re doing over there. So this podcast episode was recorded on February 20th, 2018 thanks to Kathy Reeves, Judy Hayes, Isidro Reyna, Kelly Humphries, and Ryon Stewart.

Thanks again to Dr. Andrea Hanson for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.