“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

For Episode 102, today’s leaders of the human spaceflight programs at NASA discuss how Apollo 11 influenced their lives and careers and share their thoughts on the value of putting the “human” in human spaceflight. The interviews for this episode were recorded from June 6th to July 3rd, 2019.

Check out the Houston, We Have a Podcast Apollo Page for all of our Apollo 50th anniversary episodes.

Transcript

Pat Ryan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center. This is Episode 102, “The Next First Steps.” I’m Pat Ryan. On this podcast, we talk with scientists, engineers, astronauts, and other folks about their part in America’s space exploration program, and today, that means getting their thoughts on space exploration of the past, as well as of the future. We hope you’ve heard — NASA’s been celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing — big parties. Well, two weeks ago, Gary talked with NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine about the significance of the anniversary, and the agency’s current plans to return astronauts to the Moon in the next few years. Last week, he and JSC historian Jennifer Ross-Nazzal hit on some of the lesser-known stories of Apollo 11, and we heard a few Apollo veterans share their memories of when they made history. The thing about that history is, the chances are you don’t remember it. About 65% of the population of the United States today is under the age of 50. That means for roughly two out of every three people you meet, the first landing of human beings on the Moon is a topic from history for them. It’s not something they experienced. Well, I do remember 1969, and believe me, it was a huge deal. The fact of NASA meeting President Kennedy’s goal of landing men on the Moon in the 1960s was mind-boggling for those of a certain age who never even conceived of such a thing in all their natural-born days. And for many of those who were children during that historic summer, it set their lives on a new course of scientific and technical study, and for some of them, a career in the space program. Over the last few weeks, I’ve had a chance to put a microphone in front of some of the leaders of the human spaceflight programs and offices at NASA today, to hear their memories of Apollo 11 and learn how that influenced their lives. But also to get them to share their thoughts on the value of putting the “human” in human spaceflight, and to talk about why they’re so jazzed about the emphasis within NASA today of creating a sustainable human presence on the Moon soon. As you’re about to hear, these discussions of the past very quickly turned into dreams of the future that go far beyond the Moon. Ready? Here we go.

[ Music ]

Host: We can read about history and study it as a set of facts, or we can try to get inside the history by living it through the experience of others. It turns out that most of the people who are leading NASA’s human spaceflight programs today have their very own real memories of the Apollo 11 moon landing that happened 50 years ago this month. It was, for them, a real thing — an experience they lived. And today, they can talk about it so the rest of us can share it, and can see how it informs today’s human spaceflight programs, and how it’s influencing what NASA plans to do next, starting with the return of astronauts to the Moon by 2024. Eagle landed on the Moon on a Sunday afternoon at 3:18 Houston time. Neil Armstrong put his first boot print in the Moon dust at 9:56 that evening. So most of the kids of that day were all in exactly the same place to see this piece of history unfold. They were in front of the TV, at home, with their parents, and that included several of those who would grow up to work in the human spaceflight program, and who, today, are in positions of leadership, including Mark Geyer, the director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Mark Geyer: I was 11, and so — and I lived in Idaho at the time, Boise, Idaho. We had three channels — no ABC, just the other three. We had a PBS, and so we had three channels.

Host: Nice.

Mark Geyer: And I remember that day — my brother and I, we went to the convenience store and bought those space sticks you might remember, and they were like chalky-tasting sticks. There was vanilla, chocolate — but there was — cool, because it was like you were in space. We did that, and then, when it landed — and then, I remember it being in the evening. I’ve talked about it before — using our fireplace tools, pretending I was collecting rocks on the surface, as Neil was — Neil and Buzz were walking around. So I remember that. I remember the living room. I can — and my mom was there. She stayed up with me, and we watched it together. So that was really cool.

Host: The International Space Station program manager, Kirk Shireman, and the Orion program manager, Mark Kirasich, have similar memories.

Kirk Shireman: I remember as a young child — I guess I was six years old. I remember, very distinctly, watching the first steps on the Moon. You know, it was a big deal for our family. I remember the quality of the TV wasn’t very good, although at that time, I don’t think it was a big deal. Even now, I remember — I remember the quality not being that good, but that was amazing, to be — even see it.

Mark Kirasich: Oh, my goodness, I — it is clear and distinctive like it was yesterday, one of the most vivid memories of growing up. It was July 1969. I was nine years old at the time. I was sitting in the living room of my family’s house where I grew up — in case you were wondering, 1500 South Highland Ave in Lombard, Illinois.

Host: Okay, we’ll all run there now [laughter].

Mark Kirasich: Yes.

Host: Look at the picture.

Mark Kirasich: And I was — I was sitting on the couch in our living room with my dad on one side of me, and my little six-year-old sister on the other side of me. And we watched the landing, and I was glued to the TV set. And after Neil and Buzz actually walked on the Moon — while they were walking on the Moon, there was a cut-away to a commercial or something. My sister and I dragged my father out and into the street, because we wanted to look up at the Moon and find Buzz and Neil. We didn’t that night, but it was clearly one of the most vivid memories I have from my childhood.

Host: The memory of that day is a little bit different for the woman who, today, is the manager of NASA’s commercial crew program, and that’s because Kathy Lueders was in a very different time zone 50 years ago.

Kathy Lueders: We’re all getting old.

Host: I know.

Kathy Lueders: I mean, I have a memory of Apollo 11.

Host: So do I. Yeah [laughter].

Kathy Lueders: But I — it’s — it’s of my dad. I was living in Tokyo at the time, and my dad woke us all up early, and said, “You need to come down, because this is, like, a memorable moment.” So we come down the stairs, and of course, on a black-and-white screen, you know, dragging us in, and you just see this little picture of people climbing down a ladder and standing on the Moon. And I — and, you know, at the time, I was five. And so — you know, but it’s always been this kind of distant memory of seeing people on TV standing on the Moon. That’s just amazing.

Host: John McCullough had something of a different-than-usual experience of the first moon landing, too. Fifty years ago, the man who now oversees the Johnson Space Center’s support of all NASA exploration objectives as director of exploration integration and science was a preschooler on a family road trip.

John McCullough: I absolutely do. I have actually three space memories from when I was very young, very formidable, that stuck with me, and still stick with me today. And so, the first one is Apollo 11. I was four-and-a-half years old. We were on a family vacation. We traveled 1000 miles from — I lived in Ohio, and we were going to Minnesota to visit some family friends. And I remember going across the Mackinac Bridge, this big, giant bridge, and I remember stopping and watching in the black-and-white TV the Apollo 11 landing. And that was a huge, huge moment. The whole family gathered around and watched that piece of it. So it was a big deal.

Host: You didn’t stop and watch it in the car?

John McCullough: No, no. We were — we were at a house, so it was good. But it was a little black-and-white, you know, console TV. I remember it vividly. So we still talk about that periodically.

Host: There are some leaders of human spaceflight in America today who are too young to remember Apollo 11, like Lara Kearney, the deputy manager of the Gateway program, and Steve Koerner, the director of flight crew operations at JSC.

Lara Kearney: Yeah, I was about seven months old when Apollo 11 happened, so I don’t have a direct memory of Apollo 11. But I do — by the time the Apollo program was coming to the end, they were flying their last few flights, I was about three, three-and-a-half. And I do remember that.

Host: Really?

Lara Kearney: I remember watching on the television with my family, and seeing something that looked really cool on the television. I — you know, looking back at it now, I had no concept of what a significant achievement it was at the time, but I definitely remember watching it on television with the family.

Host: And having some understanding of what was happening?

Lara Kearney: Yeah, I definitely think so. I mean, it was clear to me at the time that it was a man, and that man was on the Moon, and that was very different than being on the earth [laughter]. So, you know, even as a child, I understood that that was kind of a big deal. Just — you know, at that point, no appreciation for the magnitude of the effort that had to come together to make something like that really happen.

Steve Koerner: You know, I was very, very young on Apollo 11, so I don’t have a specific memory that ties me to Apollo 11. I do remember two things in the Apollo program. I can’t pintail them to an exact mission, but watching on a grainy black-and-white television Apollo astronauts standing on the Moon — I couldn’t even tell you, at that age, who — what — which astronaut it was standing there. But I can remember family gathered around, watching on this grainy black-and-white television an Apollo astronaut standing on the Moon. At the age I was at, I don’t think I appreciated the significance at the time. Fast-forward a couple years later, and I believe it was an Apollo Soyuz capsule that we went out in the backyard and we watched in the night sky as it circled the earth. We could see it go overhead, and even then, at a young age, in the early ’70s, thinking, “How is that possible? People are on that?” And I remember just questioning the how.

Host: Others of today’s leaders are younger still. For Holly Ridings, the chief of the flight director office here in Houston today, her first memory of Apollo 11 came from a science teacher.

Holly Ridings: Wow. The first thing I remember learning about Apollo 11 — so I was very young when I sort of had some awareness of space. So this is elementary school.

Host: Okay.

Holly Ridings: And I had an amazing science teacher. Her name was Ms. Daniel. We called her Science Daniel, not necessarily to her face, and so she really was excited about space. And of course, being the age I am, we would go to the cafeterias and watch the shuttle launch at the time. Again, this is about the sixth grade, but, you know, she did an amazing job of explaining to us, you know, space, and how we’d arrived at that point, which obviously — you know, you had the Apollo missions that came first, much before we had the shuttle. And so, you know, that’s kind of my first memory of understanding, you know, one, the concept of human spaceflight, right, and just that amazing endeavor, and two, the history of how we’d arrived, you know, at that point in time, again, when I was about in the sixth grade.

Host: As the leaders of America’s human space exploration programs today experienced the Apollo 11 moon landing in different ways, so too were they influenced by it in different ways. For people like Mark Kirasich, the impact of Apollo 11 was direct, and its influence never wavered through their lives.

Mark Kirasich: It not only inspired my education and career, it changed a lot about my family’s life for me, starting with our next family vacation. We — in the summer of 1970, our family vacationed down at the Kennedy Space Center. We were in Coco Beach. I still drive by the hotel on the A1A Highway where we stayed that year. So it changed a lot about my life. I was really — Apollo inspired me, if you will. It interested me in science and math, and I don’t know that I was smart enough at the time to know I wanted to work in the control center, wanted to be the flight director. But it definitely pulled me in that direction.

Host: And was that what you studied in school, for example?

Mark Kirasich: Yeah, that’s when — and I went to high school, studied math, science, and I was an engineer at the University of Notre Dame.

Host: Most of the others say that the Apollo 11 mission was a strong part of an influence that was exerted both before and after those couple of weeks in July 50 years ago. Here’s Steve Koerner, and then Mark Geyer.

Steve Koerner: At the time, I don’t think, either watching the Apollo event on the television or seeing that capsule in the sky, I definitively said, “Hey, that’s what I want to do.” I just wasn’t knowledgeable enough in knowing, at that young age, what that even entailed. But as I — as I aged, as I watched rocket launches subsequent to that, that same inquisitive “how” kept resonating, and ultimately, led me to look into pursuing engineering as a career choice, or a college major, to state it that way. But absolutely, I think it was linked to those events of, “How is this possible? How is this happening?” And as I got smarter and realized just how hard human spaceflight is — boy, that was an incentive to pursue.

Host: And you stuck with it. You’ve worked at NASA your whole career, right?

Steve Koerner: Yeah. I was fortunate straight out of school. I had an internship while going to school, and was able to join NASA straight out of school. So I’ve been with it — had different roles throughout the years, but human spaceflight is my passion.

Mark Geyer: It wasn’t just that one moment.

Host: Okay.

Mark Geyer: I remember the Gemini launches, too. I remember — I had tonsillitis. I remember being in the hospital, and they decided it was time to take me in. And there was a launch about to happen, and I was upset that I wasn’t going to see it. So I remember the Gemini launches. I remember all the Apollo launches. My brother and I had the models. We knew how an orbit rendezvous — we knew how all that stuff worked, at least to the level you could as a kid. So to me, the landing was a piece of that, a big piece, right, because it was success. But we’d been — I’d been following it long before then. It was very exciting.

Host: And I take it that that was a goal for you, then, to want to be in that program in some fashion?

Mark Geyer: Yeah, I knew I wanted to be a part of it, because, one, it was very exciting. It looked very difficult, and also, that it meant something. You know, it was more than just — I don’t know. It meant something bigger than myself. It was part of a national — actually a world thing. I mean, I just remember all these big events, how many people would stop and go to their TV — not just the landing, but all sorts of things, Apollo 8, everything. So it just meant — it was — it’s hard to put it into words, but it was kind of a feeling. It was more of a national focus, and I said, “Wow, that would be great, to be a part of something like that.”

Host: For John McCullough, the Apollo 11 landing was inspiring, and motivating, but only the first of three big events he remembers.

John McCullough: The other events — obviously one of them is — really, my mom was very supportive, and I would go in the backyard at a very young age and dig up rocks. And she would convince me they’re moon rocks, and I was doing the right thing. And they were cool. And it was downtown Cleveland, so it was, like, pieces of concrete and stuff, you know, but it had holes in it and stuff. And she’s like, “That’s a moon rock,” you know. She’s right, right? The Moon and the earth are joined, so — so yeah, it’s all joined in one piece. And then, in the early ’70s, there was a comet that came through, and I remember the big deal about that comet, Kohoutek. It was a big deal, and all three of those events kind of — by the time I was in fifth grade, I wanted to be an aerospace engineer. And I was going to do stuff in the space program.

Host: For Lara Kearney, the more direct influence came during high school from the space shuttle program, the first flight of Sally Ride, the loss of Challenger. But even that didn’t set her on a course straight to NASA’s door.

Lara Kearney: I was actually not one of those people that went to college saying, “I’m going to college to go to NASA.”

Host: Okay.

Lara Kearney: I was, again, more interested in just combining my love of engineering with my love of the, you know, human, and medicine. And towards the end of my college career, NASA was at Texas A&M, where I was a student, recruiting for biomedical engineers, or the folks that sit console, you know, during the missions, and take care of the crew. And I think just the light bulbs went off for me. I’m like, it never really dawned on me that, with that kind of background, I could work in the space industry. You usually think of aerospace engineers or things like that, and so that made a connection for me. And that’s how I came this direction, is more through the biomedical engineering and space-life sciences path.

Host: Kathy Lueders started off on a path that led in an entirely different direction before she was re-vectored to the space program.

Kathy Lueders: I’m not one of those people that said from that, “I’m going to go work for NASA.”

Host: Right.

Kathy Lueders: I said, “I’m going to go off and work on Wall Street,” and then I kind of — after going, and going and getting a business degree with a finance background, and doing a couple other things, I came back and said, “I want to become an engineer.” And as I was working through engineering, then I started co-oping with NASA, and started realizing really how to apply some of the practices that I’d learned through my business degree, and kind of meld it, then, with my engineering degree. And seeing kind of the value of what NASA does from an engineering fundamental — it allows us to do a peaceful engineering job. You know, I started realizing when I was coming out of school — and you start looking out there at what are the opportunities for engineers at the time. A lot of the defense contractors were pulling people in, and what you realized was — I realized I had a chance, from a NASA perspective, to apply my engineering knowledge in a way that was going to further mankind. And how many places can you do that? When I was coming out of school — and this is about early ’90s. At the time, people were really struggling with, “Am I going to go — where am I going to go do my job? Am I going to go work in a place where I’m building a product, which is a noble goal? Am I going to go build, you know, different things that are going to make us safer?” That’s also a noble goal, but people were conflicted about the things that make you safer are also things that kill people. And so when you have a — you — I really realized, you know, as I working the co-op, that I have a job that I can go work to be able to further our knowledge, and perform a mission in a way that not only is going to help us as a country be able to expand, but also be able to expand our knowledge for all the people on the earth. I grew up in Japan, and so you — when you grow up overseas, you realize that it’s — really is a world community. And as a world community, it’s always been really important to me that we get to operate as a world community. And so, the great thing with NASA is, you get to operate as a world community with other space-faring nations, and it’s a way to do that peacefully.

Host: For others, the influence of Apollo 11 did contribute to their education and career path, but actually became a stronger influence after they got to NASA. Kirk Shireman —

Kirk Shireman: I don’t know that that event itself inspired me to come to NASA. I don’t remember it that way, but I think that event really has inspired me at NASA. You know, what I remember is that, of course, people walked on the Moon. That — the biggest thing to my life certainly since that point was that we can do anything. And so, the things that we’ve accomplished since then, the things that we do, I would say, every day — there’s really nothing we can’t do, because we were able to put people on the Moon. So of course we can do all these things that are put in front of us. So I think it’s really been more of an inspiration in terms of the boundless capacity of humans. I think we can do anything. Can we put people on Mars? There’s no question in my mind, and I think it all ties back to that event as a young child.

Host: All of these folks have spent some or all of their careers working as part of the team, executing a coordinated plan to put human beings on top of the controlled explosion that is a rocket launch, and shoot those people into space to explore. I wanted to know why they feel it’s important, to use the old phrase, to have a man in the can. Why do you think it’s important that we send people to explore space?

Holly Ridings: I’d say for me, personally, it transcends, you know, all of the challenges we have in the world today, just with different countries, different borders, different perspectives, and if you think about it, it just ties every human together. Right? It’s this amazing endeavor that takes just so much energy, and technical expertise, and fortitude. And you get up to space, and of course, I’ve not been myself, but you speak to the astronauts. And of course, we have the benefit of sitting in mission control, watching the beautiful pictures come down every day, and you just see the planet. And so, really, to be a part of experiencing that, and making that happen for the entire world, you know, really to move us forward as a human race.

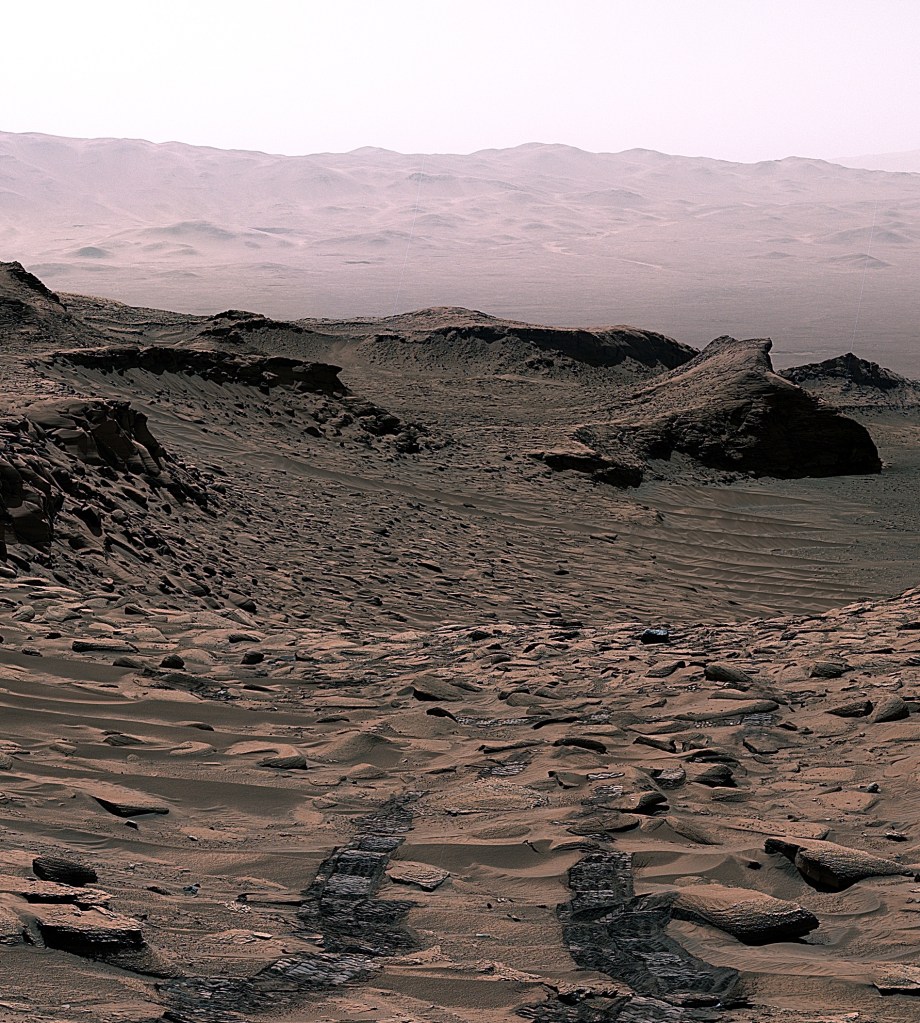

Mark Geyer: The human mind is an incredible machine, and we — the mind is capable of learning and adapting so much more than any computer that we may ever develop. And we saw in Apollo that, when we sent those scientists to the surface, their ability to learn, and adapt, and enhance what we were trying to do — we just multiplied our capability so much more. You know, the rovers on Mars are incredible machines, but even then, they’re limited. So that’s number one. Number two, I think it is — you know, I believe that the — that our destiny as a species is not limited to Earth, that we will go out into the solar system. And so, to me, this is the beginning of that destiny, too.

Steve Koerner: Asking the first folks that sailed the seas, “Why is it important?” Or asking the first folks that flew, “Why is it important?” You look back, and now, it seems commonplace that, of course, it was important. But I don’t know that they started off with all those answers, but that inquisitive human nature of — this is something that ought to be pursued. So that’s kind of at one almost general level. I’m not sure what the right word there is, but for me more personally, it’s the opportunity to influence in a way that’s significant. Human spaceflight — I mean, I can’t think of a better time to spend — a better way to spend my time for myself personally, challenging me, but also contributing to my kids, my family. Human spaceflight is an impressive, grand, bold effort that, to me, is absolutely worth it, from a — again, a personal perspective. In anything I do, I look for three things. I want to have fun. I want to provide value, and I want to learn something. And I challenge somebody to point out something other than human spaceflight that could more maximize those three things.

Host: Now, we do — we have explored space without people. We’ve sent robots, and landed them on Mars, for example. Why is it important to send people out there?

Steve Koerner: Yeah, I think sending people is significant from the perspective of adaptable, flexible, understanding the situation, being able to respond to the unknown. If it were routine that we could write a script that allowed a robot to pick up a rock, fine, but if we programmed it to drill an inch, and we realized, you know what, two inches — I see something there. I can respond. I can adapt. Just having that ability to overcome obstacles, being able to reason and think makes sense to me from a practical perspective. And don’t get me wrong — I think this — robots serve a huge, huge piece of this, and being able to go with the technology that’s available. Man, that only makes the human aspect more important, but — exciting.

Mark Kirasich: Yeah, well, there’s something about having a person, having a human on a mission. First of all, take our — take our one orbital flight test to date, exploration flight test one. It was — there was nobody on board. It was a four-hour flight, but it was a flight that went higher in altitude, in a more energetic orbit than any other spacecraft designed for people had done since the Apollo program. And it — and I had a feeling — I think everybody in the program at the time had a feeling for a short period of time, a couple hours before and after on that day — it felt like the whole world stopped to watch, because here we were doing something really bold, really brave again. So it’s — I think it’s — there’s a factor — there’s something that happens when you bring people into this endeavor that changes it from just a machine to something that more people relate to, get excited about.

Host: Does it make it seem more real to people, do you think? Is it something like that? That it could be me over there?

Mark Kirasich: I think so. I think so. That’s definitely — it’s one of the reasons — it’s one of the — one of the feelings that affected me, yes. Yeah, it’s a person.

Kathy Lueders: I think people see themselves as explorers. It was interesting to me, the social phenomena of anthropomorphizing Opportunity, right?

Host: Uh huh.

Kathy Lueders: I mean, my children came home from school, and my daughter was crying because Oppy died — like, died. You know what I mean? It was, like, terms like that, right?

Host: You’re talking about the Mars rover.

Kathy Lueders: Yeah, the Mars rover, like Oppy died. And I think it — that shows that we see ourselves — you know, it’s not — it’s not — we see ourselves on these other worlds, you know? I’m always amazed — I used to read Isaac Asimov when I was growing up, and this concept that we’ve always seen that we are going to be other places. It may take us time to get to these other places, but we’re not going to just stay here. And I think that’s reflected with — when we go send a rover out, we are finding a way to put eyes on that rover, and we’re finding a way to make that rover us. And I think it’s just this — there’s this inherent part of us that is about — if we know of a place, how do we go see that place? And it’s kind of what got people to get on a boat and go to a shore, and we actually, in some ways, have more knowledge than they did about the worlds that they were going to in some places, right? Now, the challenges we have are — may seem to us way greater, and I’m sure at the time — if you’re — I’m always amazed when you see those rickety boats, and you think, oh, my gosh. You got on that boat, and then headed out into the ocean? Like, that was crazy.

Host: That was state-of-the-art.

Kathy Lueders: Well, that — but that was also crazy, right? And so — so, I mean — but there’s probably some people that think, hey, you go get in a little tin can and go out in the netherworld, and that’s crazy. But look at what came out of it, you know? I think sometimes we don’t know what’s going to come out of it. And — but we do know what has come out of our exploration activities in the past, and we know that if we don’t explore, we’re not going to ever know.

Kirk Shireman: Part of being a human is seeing it through someone’s eyes, and so it’s — today, it’s — the easy analogue is music, or art. You know, those things are part of the human condition. I think our lives are rich because of those things. We need humans, the ones who can go and describe it to those of us who didn’t get to go. We need them to be there and describe it. So I think not only do we need them to be part of the system, we need them to be part of the experiment, but we need them to be able to bring the rest of humanity with them. And I really do think that, in the near-term, that’s what human spaceflight is all about. Long-term, there’s no question — I think the species needs to be a multi-planet species. And so, for — I believe, ultimately, for the survival of the species, we need to be able to live in other places. Now, that’s probably not in the next 10 or 20 years, but I think that’s the direction that the human species needs to go.

Host: You probably have your own reasons why you believe in putting the human in human spaceflight, and they very likely go beyond the Cold War political reasoning that was part of the calculus when President John Kennedy set the goal of landing Americans on the Moon in the 1960s. When I asked today’s guests for their thoughts about why it was important to return people to the Moon, none of their answers had to do with political motives. They believe in making a practical use of the Moon, which is relatively close to Earth, to get ready for missions that will go thousands of times farther out into space.

John McCullough: Learning those 30, 60, 90-day missions around the Moon and on the surface allow you to use those resources, understand how to work in that environment. That’s 1000 times further than the low Earth orbit missions on station that we do, 1000 times further — hugely different problem. Well, Mars, the next step, is 2000 times further than the Moon.

Host: Two thousand times?

John McCullough: Two thousand times further than the Moon, and that is a whole — you got to build those capabilities. It’s a really good proving ground before you go to the next step, but you’ve got to take those steps. And you’ve got to take them before — when the time allows you to get there, and get it done. Otherwise, you’re not going to survive as a civilization.

Lara Kearney: So going — so the ultimate goal is to get us to Mars, and then beyond, of course, but to get us to Mars. But going to Mars is really, really hard. Well, going to Mars and bringing someone back safely is really, really hard, and so the Moon really provides for us a way to practice, and learn the things we don’t know already, right? And so, to go back to the Moon in a long-term sustainable way, learn how to live there for a period of time, learn how to, you know, live off of the resources on another planet, learn how to take care of the human body in an environment that it’s not meant to be in. Being on the Moon for a sustained period of time will help us learn all those lessons while we’re still relatively close to home, right, before we take that really big leap onto Mars.

Host: Two hundred fifty thousand miles is your definition of relatively close [laughter].

Lara Kearney: Relative to Mars, that’s pretty close.

Holly Ridings: Yeah, so flying in low Earth orbit, right, which we’ve been doing for many years, you know, with the Space Station, and before that, with the shuttle, you know, teaches you a certain set of skills, right? How you communicate with people in orbit, how quickly you can get home if something goes wrong — you know, once you get outside of low Earth orbit, go farther away from the earth, you know, to the Moon in this case — you know, you have a different set of technical problems to solve. And if you’re a flight director, and working operations, you think about in terms of risk. Okay, how long does it take to talk to someone? They’re on the backside of the Moon. Can you talk to them at all? Something goes wrong — can you get home? How often can you get home? How fast can you get home? And when you think about all of those challenges that we will get to solve, and then sort of move that thought forward even farther out, inside — outside of low Earth orbit, past the Moon, and into the solar system, those challenges only get more complicated. And so, you have to transition to a system that can’t rely on, you know, everything back home helping you out. You’ve got to have more autonomy with the way we look at flying in space, and so that’s just sort of one example of how much we’re going to learn by getting to the Moon and staying there.

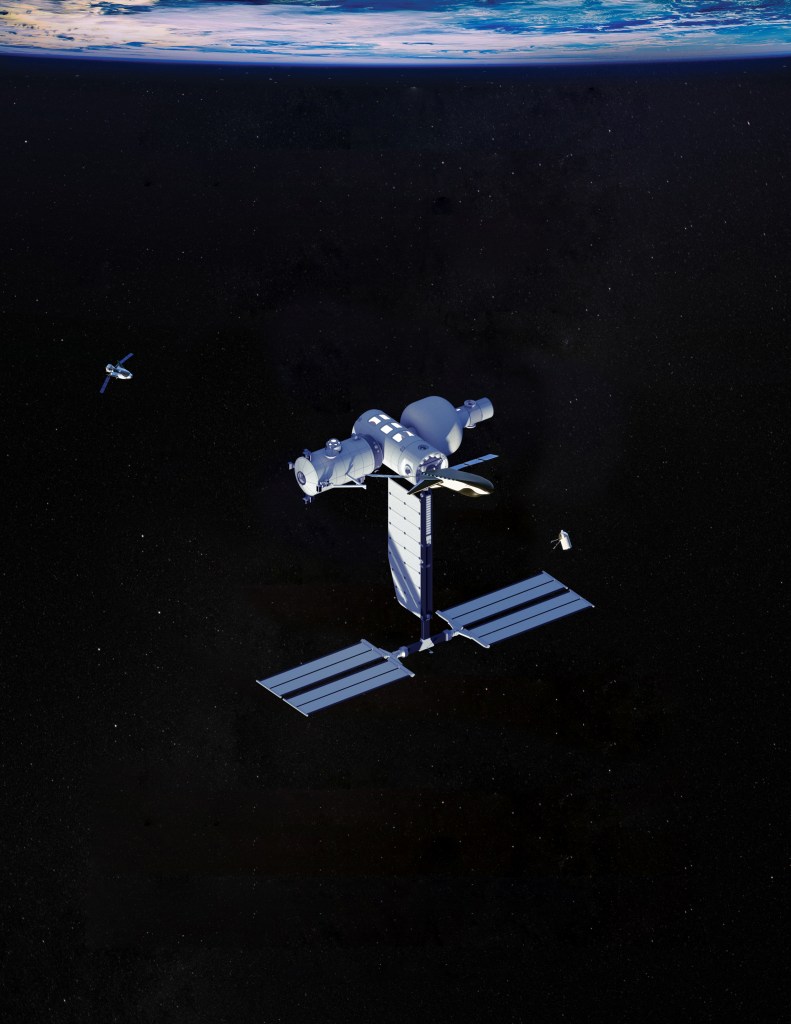

Host: Let’s keep in mind — in today’s NASA, under the Artemis program, the goal is not to just put people on the Moon, as we did two generations ago. The goal is to return American astronauts to the Moon by 2024, and establish a sustainable presence on the Moon by 2028. From there, astronauts can make scientific discoveries, demonstrate technological advancement, and lay foundations for private companies to build a lunar economy.

Lara Kearney: I think part of what the Artemis program will do for us, and the Gateway, is learn how to develop and fly reusable spacecraft architectures, right? You know, Apollo — think of it as a point solution. They went to a specific destination, and they came back. The Gateway and the Artemis program will allow us — I think of it more like an infrastructure. We build an infrastructure that allows multiple spacecraft to come and go. And how do we operate that infrastructure, and how do we reuse vehicles so that we’re not disposing of them every time we want to fly a mission? And every — the more we learn about that, the more we bring the costs down, the overall costs down, and when it becomes more affordable, we can start doing more. And when we can do more, we can go farther.

Host: Kirk Shireman’s been working on the International Space Station program since the first component, the Zarya module, was still in a factory in Russia. So he knows something about creating a system that will support a vehicle in space, or an outpost off-world.

Kirk Shireman: Sustainable’s a really hard thing. It’s a really difficult thing.

Host: Ask the International Space Station.

Kirk Shireman: [Laughter] Yes, and the further away from home, the harder it is. It — so even learning how to be sustainable in that sense is going to be difficult. Now, the Moon — the Moon is a lot further away. In the International Space Station, you can be on the space station, and be home in a matter of, you know, three-ish hours. In fact, we did that here Monday night. So — but if you’re in the Moon, if you’re at the Moon, certainly on the surface of the Moon, but even in the vicinity of the Moon, you might be nine days from coming home.

Host: Wow.

Kirk Shireman: And so, that’s a big change. You know, three hours to nine days — and so, even that, and keeping humans alive and safe in that environment I think is a great thing to learn. How you put things on the surface, and then how you hook up to those things, how you link up with those, and when you arrive there — a lot of practicality. How do you build things with the resources that are present on the Moon was great, and that technology can be used here on the planet, so — on Earth. So what we do out there, I think, will also have benefits back here. I think people are already working on building habitats with lunar soil, lunar regolith right now. If you can do that, you could do it here with the Earth. And so, I think there are benefits that we’ll get back here, even from basic engineering things that we’ll do on the Moon.

Host: And presumably, the — what you’ve learned doing that on the Moon may be then applicable to doing it on other, further-away planets.

Kirk Shireman: Sure. You know, who knows? I hope so. I think when they talked about making rocket fuel out of the ice or the water that’s there, we certainly think that’s applicable in other places. There’s, you know, moons around Jupiter that we believe have water ice, and so you can envision, in the future, doing the similar thing out there. So Mars has an atmosphere of carbon dioxide, which doesn’t quite scratch all the itches for rocket fuel, but could be used to convert that carbon dioxide into useful things for a long-term human presence. So all this — even this notion of using the resources that are present I think will definitely apply not only in the Moon, but as we take the human species further and further from home.

Kathy Lueders: You’re establishing places where people can develop and actually potential use the capability that’s there. It’s not about visiting anymore. It’s about staying. This may be a 100-year goal. It may be a 200-year goal, but it’s in the same vein of — if you’re going to have a goal, it’s about can — is there ways to do it in a way that enables it to be able to expand the potential of the mission when you get up there. This is — these are hard things.

Host: Yeah.

Kathy Lueders: These are hard things. They are not easy things. We don’t have the answers to how you go do that, but in the same way, I think if we knew what the answers were today, then we’re not making our hard goal to enable us to be able to push the learning. And really, that’s, to me, the value. That’s the value proposition. The value proposition is having a goal that’s so hard we don’t know how to do it yet. And through the figuring-out-how-to-do-it, that’s when we’re expanding human knowledge.

John McCullough: I think going and learning how to work there, and, again, figuring out how to use resources where you find them to propel you to the next milestone is what this is all about. If we can’t live and work in space, there’s only a finite amount of space and capability on this planet. And again, we need to protect this planet. We need to preserve it, and we need to push out and learn how to live in that — what is the 99% of the rest of the space we have, right, is that type of environment. So we need to get to that environment, and understand, and live there.

Host: You’ve talked about the things we need to learn in order to provide for our own future, as well as supply future exploration. Can you give me a couple of concrete examples? What kinds of questions do we have about future space exploration that this sustainable presence on the Moon is going to help us answer, to get us ready to do those future things?

John McCullough: It varies significantly from the simple things that we do and take for granted every day in this environment — and we’ve learned a lot about that on space station. But 1/6th gravity is different than zero gravity, and it’s different than full gravity. And so, that environment, from a radiation and a thermal perspective, plus 200, minus 200 degrees, day and night, or shade and light, is a huge, huge challenge of environment to work in. And so, we have worked in that environment, but being able to work there in a way that you can’t run home and get spares or supplies on a daily basis means you’re — so for example, our spacesuit design — it’s significantly more versatile, and significantly more flexible in terms of redundant systems and capabilities. So that when you’re out there on your own, and you’re roving, or you’re further away from your vehicle, you have capabilities that allow you to get back safely. So managing how to operate safely, managing the risk, and learning how to accept the kind of risk that we have to take to get out there are huge challenges for us to face.

Holly Ridings: You can go camp in the mountains for a week. You have to have a certain set of stuff in your backpack. You’re going to go build a cabin and stay there for three years. That’s a very, very different — different challenge, and I think that the world is really excited about taking on that challenge.

Steve Koerner: And you think about what’s necessary — what resources are necessary to launch that capsule with people in it into space. Well, we’re not going to have that infrastructure on Mars, or we’re not going to have that infrastructure on the Moon. So what’s available that we can take advantage of to be able to do this effort in a way that’s actually — makes it the potential to be successful? And so, you know, you hear the administrator talk today about discoveries of water or ice on the Moon.

Host: Right.

Steve Koerner: And why we maybe should head to the South Pole of the Moon — things like that. What are we going to find out when we get there that enable us to say, “Ah, okay, here’s what we can do with what we’ve uncovered.”

Host: While the Artemis program is relatively new, it’s clear that the men and women who lead NASA’s human spaceflight effort have been thinking about putting people on the Moon again for quite some time. And it probably won’t come as a surprise to you to learn some of the reasons they put stock in just such a future. Steve Koerner, the chief of the JSC flight operations directorate:

Steve Koerner: Looking back over my career, some of the most powerful things that I didn’t even realize I was a part of as it was happening was that alignment around a common goal, the International Space Station. Human spaceflight’s hard, and yet, numerous countries aligned around a common goal, and able — were able to put that amazing machine in orbit. We put aside our differences, whether where we lived geographically, or our political persuasions, or whatever, because we were focused around a common goal, human spaceflight. Hugely powerful to look at what can be accomplished when your team, your company, your organization, your country, whatever, is aligned around a common goal, and to me, that’s been the most satisfying piece of this job, is seeing — being a part of a goal that I think is hugely significant, and watching — watching the collective organizations, the entire team around that same goal be successful.

Host: Johnson Space Center director, Mark Geyer:

Mark Geyer: We talked a little bit about what motivated me when I was a kid, and I remember — I remember that time. I remember the excitement, and the newness of going to space, and I remember how it affected the whole culture. You know, I had a Major Matt Mason toy, and I watched “Star Trek.” Right? It all started in about that same timeframe. So it kind of changed the whole vibe in that timeframe. So, NASA’s done a lot of cool stuff in between that. The shuttle was incredible. The station is really a world wonder, and we’re about to do more of that. But I do think going back to the Moon is such a significant step that I do believe it will amp — it’ll ramp up the attention, and the interest of the kids in this country. And if we can show them that they have a place in that future with these companies, or with NASA, and that we can continue to bring them along, and help make sure that they have the opportunities they need to get the education they need — I mean, whether they end up at NASA, or Boeing, or SpaceX, or not, it doesn’t matter. If they’ve — if it motivated them to get through science, or even, you know, liberal arts and everything else, it gets them excited enough to get through their degree, and we have an educated workforce, that’s better for everybody. And I do feel like Apollo helped, even if a lot of people didn’t end up at NASA. I still think it helped our overall youth and the country in general.

Host: Chief Flight Director Holly Ridings is one who sees potential rewards that go beyond the engineering achievements that will come out of the Artemis program.

Holly Ridings: When I think about what we can learn — you know, there’s — so there’s the technical answer, right?

Host: Okay.

Holly Ridings: We can figure out how to, you know, build spacecraft, and land on the Moon, and stay there, but I’d say that I’m more excited about what we can learn as people, right? You know, how to bring hope, and energy, and excitement to the world, you know, something that everyone looks at, and wants to be a part of, and believes in.

Host: Last word today to International Space Station Program Manager Kirk Shireman:

Kirk Shireman: The thing is, going to the Moon is a really, really difficult thing, and people remember it now. People my age certainly remember it, but people that are younger, which is, you know, most of the population of the world, haven’t ever seen that. And I think that will be really cool. One of the great things that I didn’t notice when I was six years old, but as I have been on the International Space Station program, had a chance to travel around the world. And people all over the world know NASA and remember that event, and in fact, I see pictures of people from all — different countries all over the world stopping to watch that first step. And I think that’s something really, really cool. It’s something that brings the whole together, when a human being steps foot on another body, and that’s something I think the world really needs, something to bring it together. There’s so many things today that drive us all apart. Wouldn’t it be great to have something like that, that would bring the whole world together? So I’m really looking forward to going back to the Moon. I think it’ll be great for NASA. I think it’ll be great for the United States, but it’ll be a great thing for the whole planet.

[ Music ]

Host: Well, that was fun, talking with these men and women who lead human spaceflight at NASA today. Hearing their memories of Apollo 11, and getting some insight into how that historic first moon landing 50 years ago is connected through the space shuttle program right into today’s efforts with the International Space Station and Commercial Crew and cargo programs. Into the development of the programs that will help give life to the Artemis program, the Orion vehicle, the Space Launch System rocket, and the Gateway. I hope you enjoyed listening. You want to get more into the details of what’s on the drawing boards right now? Go to nasa.gov, and follow the links to “Moon to Mars” and to “Humans in Space.” You can go online to keep up with all things NASA at nasa.gov, but also be a good idea for you to follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. You will thank me. When you go to those sites, you can use the hashtag #askNASA to submit a question, or suggest a topic for us. Please indicate that it’s for “Houston, We Have a Podcast.” You can find the full catalog of all of our episodes by going to nasa.gov/podcasts. While you’re there, look around at all the other NASA podcasts that you can find. They’re all available there at the same spot where you can find us, nasa.gov/podcasts. The interviews for today’s episode were recorded from June 6th to July 3rd, 2019. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Gary Jordan, and Norah Moran for their help in the production, to Johnson Space Center Public Affairs Officers Brandi Dean, Kyle Herring, Jenny Knotts, Isidro Reyna, and Laura Rochon for their assistance in lining up the talent. And thanks to our guests, in alphabetical order, Mark Geyer, Lara Kearney, Mark Kirasich, Steve Koerner, Kathy Lueders, John McCullough, Holly Ridings, and Kirk Shireman. We’ll be back next week.