“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

Episode 44 features Jeff Fox, Chief Engineer of the Rapid Prototype Lab at the Johnson Space Center, who tells the history and evolution of displays and controls in the space shuttle. Fox reveals details behind some of the new displays that are being designed to fly on the Orion spacecraft. This episode was recorded on March 21, 2018.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 44: Spacecraft Displays. I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. So on this podcast, this is the podcast where we bring in the experts — NASA scientists, engineers, astronauts — all to let you know the coolest information that’s going on right here at NASA. So today we’re talking about NASA’s deep space human capsule, Orion, which we’ve discussed several times on the podcast, getting an overview of the capsule, what it would be like to live on it for up to three weeks. But today’s episode is focusing specifically on the screens and how they’ve involved over time from the Shuttle era now to future spacecraft. Coming on the show once again is Jeff Fox, chief engineer of the Rapid Prototype Lab at the Johnson Space Center. He’s been on the podcast before, and he actually brought some of the audio from the test run that we’ve done on Orion, specifically EFT-1. We’ll talk about that later. And he gave us a really cool audio experience of riding on a spacecraft. And now he’s back to tell us about some of the details behind some of the new displays that are going on Orion. So with no further delay, let’s go light speed and jump right ahead to our talk with Mr. Jeff Fox.

Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host:Jeff, thanks so much for coming back on the podcast. Glad to have you back. Because you’ve already been here before, right?

Jeff Fox: Yes, sir. Thanks for having me. I’m exciting to be here.

Host:Of course. That was actually a really good episode, the one we did before. That was “Ride on Orion.” You actually brought some of the audio from the inside of the EFT-1 capsule and we got to play it in the middle of the episode.

Jeff Fox:Yeah, I remember that. That’s great. In fact, we’ve done many a tour since that episode.

Host:Really? And have you gotten any comments about the episode?

Jeff Fox:Yes, quite a number of people either approached me through email or in the hallway. And most of the feedback’s been good. Maybe they won’t tell me if it’s bad [Laughs]. But I’m very happy that I didn’t say something that sounded too bad.

Host:No, absolutely not. I’m glad to have you again because that was a really good episode. And I think this is a good follow-up to it because it’s kind of a continuation of the Rapid Prototype Lab. Last time we talked mostly about you were able to play these sounds and kind of sit in this almost simulator and feel what it was like to launch in that EFT-1 capsule, to reenter the earth’s atmosphere. But there’s this whole other section that’s dealing with screens, right, that you actually are looking at and working with the screens that are actually going to be used inside of Orion, right?

Jeff Fox:Yeah, that’s right. If you imagine the cockpit is three 8.5 by 11 sheets of paper in the portrait or vertical format separated by about let’s say 4 to 6 inches in between each roughly. And then each of those pieces of glass, those monitors are — think of a line drawn horizontally through them so you have a top half and a bottom half. So you have three of these screens, each has a top half and a bottom half. That’s the sum total of the display real estate that the crew has to view everything

Host:So take us through, like, I guess an audio tour of the Rapid Prototype Lab. I don’t think we did that the last episode. Because it’s kind of sectioned off and it’s in a building that’s — it’s the same building where the, I think, astronauts are, right? Am I —

Jeff Fox:That’s right.

Host:Okay.

Jeff Fox:And it is part of the crew office. And it’s on the fifth floor. It’s in one of the corners of building, kind of controlled access. But, you know, the main charter of the RPL is to build the prototype crew displays that are going to be flown on the Orion spacecraft, the ones the crew will use to monitor and control the spacecraft.

Host:Okay. So that’s — I’m guessing that’s one of the rooms, right? Are you actually bringing the astronauts from across the hall and saying, “Hey, sit down. I want you to see how this thing is working”?

Jeff Fox:Correct. We do do that. And yes, we have to evaluate the displays when we build prototypes. So we definitely put the crew in front of those. To do that we created a couple simulators — one we talked about before where you lay on your back and then two other orbit or up right ones. We also had to assemble all the hardware to create these simulators. So we have a 3D printer. We have folks that do some electronics work and assemble all the screens. So we have prototype displays to play the — prototype hardware displays to put the software displays on there so that the crew can evaluate what we’re doing.

Host:Okay. And they’ve got to get the experience. It’s not just, “Here’s the system, check it out.” It’s, all right, we’re going to put you in the — I guess this is the environment of Orion. This is kind of what it’s going to feel like when you’re in the real thing. And this is what the controls are going to do. So I guess kind of running through those procedures.

Jeff Fox:Yes. We wanted to give the crew a feel of that. I mean, it’s one thing to do a PowerPoint and then have somebody look at it and talk to us; it’s another thing if you can write some basic code behind it, make the buttons change or the data change in a way that would be representative of the flight so that when the crew goes through the interface with the control on Orion, it feels and acts what it look like. Now, the flight vehicle will be different in the way it implements that. But we need the feedback on how’s it working? And because we are way ahead of the — of the whole operational environment with training, we’ve got to create these things to be able to get input on these displays early enough on to get them in the design of the vehicle. We can’t wait until end because software’s obviously complicated, it’s a very long logistics tail.

Host:Absolutely. And it kind of has a history, too. So it’s not like you decided this is the best thing. This is kind of based on lessons and some upgrades that were necessary based on the procedures even back in the Shuttle days. And I’m sure you were working with some of the crews to work with some of the systems back in the Shuttle days, right?

Jeff Fox:Yes, yes. And let me give you just a little, quick history on the RPL itself coming into being. The concept of having the crew involved in evaluating and having input into the crew interface has been around for many, many years. You know, even going back, you think of the program before this, CAU for the Shuttle and also some input into X38 and other vehicles. So we had that experience, centuries of experience in the cockpit to bring to bear on this. So just to compare and contrast a little bit with Shuttle. You know, I was very fortunate. I started working here in ’84 and was heavily involved in Shuttle through about ’96 in different capacities, starting off as an instructor in the systems world. And for people who don’t know what systems is, that’s like environmental control; life support; you know, Freon loops; water loops; breathing air; APU’s; electrical power; those kinds of things.

Host:All the systems that actually make the spacecraft work?

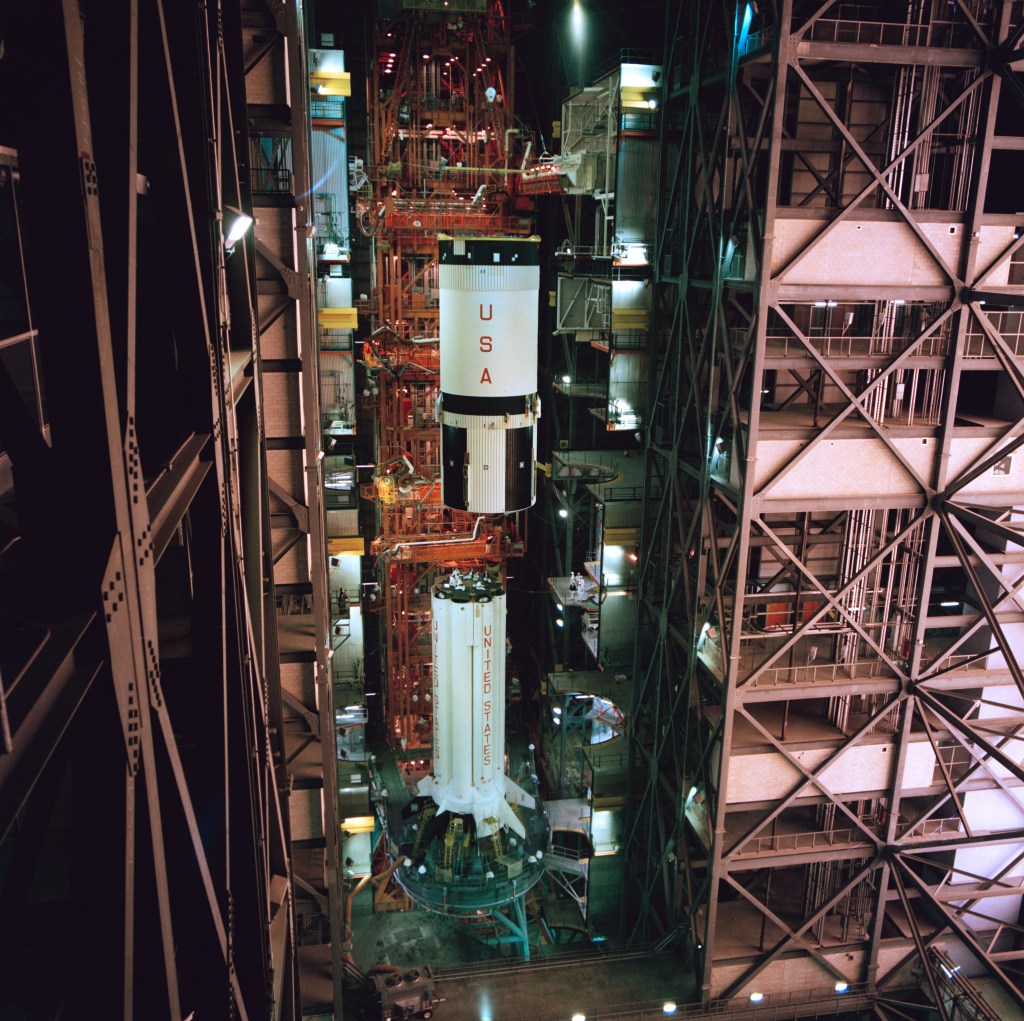

Jeff Fox:Well, there’s guidance, navigation control, propulsion, communications, rendezvous. There’s quite a number of them. So, you know, for example, on Shuttle, you know, you’re dealing with a design that’s early ’70s. You know, when you get in the Shuttle, you can see the switches have that feel of an older cockpit. That doesn’t mean bad, that just means that was the design, that was the concept. And it worked well. It served us very well. You’re talking a cockpit that had approximately in the range of 1,000 to 2,000 hard control points, be it a switch, a circuit breaker, a gauge, you know, a physical thing you could touch. Then you had — you started off with just a limited number of screens and you had a lot of paper procedures. You had up to a couple hundred pounds of procedures. And they addressed every manner of the flight phase from [inaudible] entry to, you know, post-insertions, de-orbit prep, getting ready to come home, rendezvous, RMS, you know, the robot arm.

That’s a lot of paper. It’s a stack of paper. Maybe it’s as tall as you, you know? And that’s a lot of weight, a lot of mass. But it did the job well. You know, you could pull a book out, you could put it on your lap. You could have that book that had your favorite notes in it about don’t forget to flip this switch. I always miss it in this procedure. You could get a message on your panel, what we call the F-7 panel that had kind of like an idiot light on it and a software message on the screen and go, “Oh, that’s what it is.” And then say, “Hey, I know what procedure to work.” I look at my display, which is right there, get data about it. I’d read the procedure, the procedure would say do this. And in order to do something, I had to throw a switch. So I’d go over on a switch on a panel, maybe to my left. Maybe it’s a Freon pump I have to turn off and turn a different one on. So I’d reach over and do that and it would be done. Now, it sounds like a lot, it sounds complicated, but it was very quick because everything was in my gaze immediately — the error message, the data on the display, the procedure, and the switch.

So very quickly I can get trained to see all those things. Move and throw a switch, I’m recovered. So actually, that system worked very well.

Host:And that’s — is that what you were doing as a systems instructor? You were taking the astronauts through each system and these procedures that you’re talking about, too?

Jeff Fox:Yes. So when I started off, I always like to say they were training me for several years, the crews. You know, you’re just happy to be there, you’re learning, you’re trying to stay very open-minded because you’ve got a lot to learn — still the case today. And we started off learning the individual systems one at a time as an example in something called the single systems trainer. In fact, for folks that are here at JSC, if you go over to Building 30 and you look in the lobby, there’s one of them there. And it was where you would just train one system at a time. There’s another one at Building 4 North in the lobby as well, I believe. And we would go in there and, for example, I can remember vividly one training session on the environmental control life support system. It’s just you and one person. And it was to today it’s one of the highlights being able to sit in there with the crew one-on-one and try to, you know, impart on them some knowledge about how a system works or what to do when it doesn’t work. And I remember vividly having John Young in there one time. And I’d only been here, like, two years. You know? I think I was 26 at the time.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:And I didn’t know anything too much about John other than hey, this guy walked on the moon. And I’m thinking, “Wow, this is — you know, I’m in here, I’m training him. I think he’s training me [Laughs].” So anyway, so as we got through this two-hour lesson, about half an hour in I’m just dying. I got to ask him what was it like to walk on the moon? So I just broke down and said, “I’m going to ask.” And I asked him. And I remember he started talking, and my eyes got wide and my mouth was open. And he probably talked for 20 minutes on it. And people would ask me to this day what did he say and I says,” I have no idea. I can’t remember. But I just knew I asked him and I was wide-eyed and soaking it all in.” And I said, “But I got to ask him.” So it was one of the perks, just a fun time. But that was a single systems trainer. We also had the Shuttle trainers, the simulators. Some folks might remember those. And those had all of the systems in them. Some of them we touched on earlier. And those all worked integrated together. And the instructor teams would work with the crew. And we would work through different scenarios with all the paper and the switches and voice loops and manage the data that way.

And we also would train with the flight controllers. After the crew got somewhat proficient, we would flow that day to the control center like we do today. And we were on training tea ms back behind the glass over in the control center, instigating the problems and trying to make life miserable for flight control and trying to put them in positions to make good decisions. Sometimes they went ways we didn’t even expect. So we learned from them. So.

Host:Wow. All right. I wanted to back up to that single systems trainer that you were talking about. Sounds like if you’re looking inside the Shuttle cockpit, you said there’s somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 switches. And that’s a lot. So it sounds like you’re sort of training these astronauts in stages. So you sort of put them in an environment where you’re dealing with maybe one system, and you are working on the controls and okay, these controls work on this particular system. Now let’s go to another one with this particular system. And then eventually get to a point where everything is in front of you and you have to know, and maybe you’re blending your thoughts from okay, you’re training from this system to this system. So is that kind of the process, the training flow for astronauts? Or am I getting that wrong?

Jeff Fox:No, that’s very good. In fact, we didn’t have the advantage; really, computers were just starting back then.

Host:Oh, yeah.

Jeff Fox:A little quick note. In our office — I have it share this with folks.

Host:Oh, yeah.

Jeff Fox:I remember distinctly when we were in Building 4 North, this old building that’s been around since Apollo times. There’s about six of us in this room, just jammed in. And this computer came in and we’re like, “What do we do with this thing?” Right? And it’s like it had a five and a quarter inch floppy disk for people that know what that is or if you want to look it up and see what it is. And so we’re looking at this screen, it’s got a keyboard. And we’re like, “Do you want to use it? No, I don’t want to use it. Do you want it? No, I don’t want it.” So what we did is we put it on a bookcase in the middle of the room and said, “If somebody wants to use it, they can stand up and use it right here [Laughs].” So that’s all we knew. And then we said, “Hey, but there are some guys down at the end of the hall and they got this computer and it’s got this, like, eight-inch floppy. These people must be really smart.” We don’t know what it does, but, you know, we just thought —

[ Multiple Speakers ] — they were smarter than we were. The advantage nowadays, you know, you’ve got the electronic media and you’ve got much better methods to train people with, right? But back then for us and the astronauts alike, flight controllers, you came in, you were going to learn a system, you got a stack of workbooks. That workbook — I can remember having workbooks stacked two, three feet high and thinking, “I’m never going to get through this.” So the crews would read those things. We had some classroom training and other ways to train people. Then they would work their way up, like you mentioned, to the single systems trainer, training one system at a time. They would do a lot of those, put all the pieces of all the systems together. Then if you will graduate up to something like the Shuttle mission simulator where they would be with other crew. They would have all the simulation systems together at once. And then they could fly a mission or practice a launch, or an abort, or that type of thing.

Host:Yeah. So if you’re working with a book and eventually you go through all of your systems and you know each individual part, now you’re dealing with a handbook that’s as high as you, how do you know what to flip to? How do you know — are the astronauts expected to memorize these procedures or at least know kind of what to do? Or do they have maybe people helping them along the way?

Jeff Fox:Well, there are some that did memorize quite a number of them. You know, we had a core team on the Shuttle, right, on the flight deck. You had the commander in the left seat, the pilot in the right seat, and in the center seat just behind them was the MS-2, mission specialist 2. Or I think of him more like the conductor and keeping every on track. Because, you know, you’ve got people responsible for flying the vehicle and in charge of the overall thing and the other seat maybe with critical systems. And the guy in the center, the MS-2, the flight engineer keeping you honest. So they would work together as a team working through things. So how would the crew possibly keep track of all these procedures? It’s a great question. Well, the books are split up in different ways. You’ve got books that they use on assent or launch, books or orbit, books on entry, that type of thing. Then they’re subdivided into books when you’re working in that are nominal procedures when everything is going right and then books where we call them off-nominal where everything is going wrong.

So an example on an assent, you might have the assent checklist — that’s good. Everything’s going good, I’m flipping through it, I’m monitoring things. Then you’d have a book called the assent entry systems or assent pocket checklist. And those represent different times throughout the assent where if something goes wrong, I’m going to flip through that book. And that book was further subdivided by systems. So if I had problem in one of the propulsion systems of the engines, I’d flip to that tab, read something and it would tell me what to do. And, again, it was a team effort, you know, folks watching and checking you, especially on critical switch throws.

Host:Yeah. And so I’m guessing the emergency handbooks were a little bit larger than the regular nominal handbooks, right? I’m guessing you have a lot more in case something goes wrong.

Jeff Fox:Well, there was all manner of them, you know? If you think on the critical flight phases, you know, your launch and landing, assent entry, you might have things called cue cards that were literally Velcroed to the panel, very short critical steps. So I don’t have time to get down to other things, I need some stuff right in front of me, you know? Then you had other books that were called flip books. And that might be another level of critical that may be just one off of that. Then you have another book that you would open called let’s say the pocket checklist that was after that. And maybe that’s after — further along the assent or the engines are shut down, I want to open that book because there’s other steps I need to work in that failure chain to look at things. But I don’t want to be doing that while I’m burning on engines. If my engines are good and I’m safe and I’m going uphill, I don’t want to be working a lot of the things; I need to monitor that whole flight phase and make sure nothing bad is going on. Then as I have time and the criticality is less, then I can get to follow-on recovery procedures.

Host:Okay. So it seems like there’s a lot of training that they have to do. And especially it sounds like when they’re studying these procedures, they have to know more about each — at least the steps, at least, “Okay, now I’m at this part. If something goes wrong, I got to flip to this part of my book and follow the procedure.” Not maybe necessarily memorizing the procedures each and every single one in order exactly the way it is, but maybe at least, “Okay, I know where to go.” It’s like looking at a map. Like, okay, if I were to pull out the map, I know I’m here. And then you just kind of look at the surrounding area. I guess that’s kind of the logic of training for systems.

Jeff Fox:True. Except that I would say if you talk to some of those crews, I bet the ones that had to put their hands on the switches or the displays around a certain system, I bet they’ve read and if they haven’t memorized, they pretty much know what’s going to happen. But they’re not just going to blindly execute it. They’re going to read it. Because you know when you get in the cockpit you lose IQ point. And you know you need to — you’re trying to make sure you don’t make a mistake. You’re reading it carefully. And if you need to get double checked or backed up before you throw a critical switch. But I’ll bet that they have been through every inch of that book and looked at it. Because I know I would if I was putting my hands on those switches. You don’t want to make a mistake.

Host:Absolutely. Because I guess it’s fair to say that through each of those procedures, they’ve actually practiced it, right? They’ve actually gone through, read it, at least some of them they’ve practiced.

Jeff Fox:Probably read it. Whether they’ve executed every single procedure or we have had time to throw every scenario, every failure in, in all of these books, maybe not.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:You know, a lot of them can be repetitive. Let’s say it’s an electrical system. You know? There’s all kind of electrical buses. Do you have to have every electrical bus fail, work every one of those to be qualified to work it? Probably not. But there might be some idiosyncrasies with some you want to make sure you target. Like, if you lose that one, there’s this little nuance. So as a training team and the crew, we would be sure we would do that one.

Host:Yeah. So as an instructor, I guess you sort of saw the astronauts go through this training program, to learn the systems from day one until the day they fly; how long did it actually take for an astronaut to go through that?

Jeff Fox:Well, it’s a great question and some of that varied. And I’m really stretching my memory going back. And for folks that are listening that may know better than me, forgive me. But, you know, typically once the crew — they got trained and they went in the pool, then they get assigned to a flight. And then they get some — there’s several things going on. You’ve got the dynamic flight phases of the vehicle like the launch, landing, that type of stuff that are very intensive training — hundreds of hours just in the simulator.

Host:Wow.

Jeff Fox:And you would add on flying the Shuttle training aircraft and other simulators and, you know, a lot of different things. Then you have well, the reason you’re there on orbit is to do some kind of science or payload, right? So you have other folks that are maybe in another parallel flow, working real hard to do that training. So they got to know that thing inside and out. If something goes wrong, they’re there to fix it, put their hands on it. You know? There’s similarities to Station. There’s some commanding that was available from the ground. I don’t know if it’s as extravagant as it is now. But you’re the one that’s responsible for that. And, again, so, you know, summarizing typical training flow. Well, it depended on the mission. And I’m really stretching my memory, but for some complex missions it could be a couple of years. But you would have people, you know, getting smart on payloads and other things, you know, well in advance of their assigned crew training, which typically might start about nine months out from launch where you would start to come together as a crew and do some basic stuff in the Shuttle simulator and your other satellite one-on-one type of training courses.

So the amount of time you’d spend, again, for assent entry, you know, hundreds of hours — several hundred hours just in the simulator. And then, again, another group of people doing the payloads. They might do a couple hundred hours or more just on their payload independent of you. And then we might culminate into something called a long sim where we would bring everybody together. And it might be a 36-hour or a two-day sim where you would actually run it continuously, you know, have shift changes in the control center. The crew might go home and sleep during the crew sleep period but then come back. And we would generally try to work in one of those, I believe, for each sim and we would figure out what the optimum timeline was to work. So those were always interesting.

Host:Yeah, because you were basically simulating a mission. This is what you would do in the mission. You would go home and sleep and you would be taking turns, that sort of thing.

Jeff Fox:Correct. At least get that key part of the mission that made sense. Obviously you weren’t going to do 9, 10 days, two weeks.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:But you were going to select a portion of it.

Host:So as a systems instructor, what systems were you instructing for? Was it mainly the life support systems? Did you kind of have more of a broad approach?

Jeff Fox:Systems is kind of a collection of different ones.

Host:Okay.

Jeff Fox:When I say environmental control life support, I mean, you know, the breathing air, Freon loops, and water loops, and air loops that are used to cool equipment and atmospheric conditioning and that type of thing. Auxiliary power units, you know, those are — I think most folks know what that is. Hydraulics is another one. Electrical buses, the power system, the electrical power system.

Host:So you were teaching all of these?

Jeff Fox:All these. Cryo, the cryo tanks, which drove the chemical reaction or produced the electricity, which also made the water. So those systems. Then you had mechanical systems, some of those — like the payload bay doors. Then you had a little bit of a caution warning system, I believe. So it was quite a broad brush.

Host:Wow. Yeah, you must have known those systems inside and out then, right? [Laughs]

Jeff Fox:We had to know them pretty well because you never knew what kind of question you were going to get asked.

Host:That’s right.

Jeff Fox:And at that time the flight control was a separate division. And I remember that we always wanted to put training and flight control together. And now I think we’ve successfully done that in this day and age where, you know, you know your systems inside and out on the station, you’ve been on console, and now that’s the people we want to be training the crew. Back then it was just a different model. We had the training guys, you had the flight control guys. And we might know it to one level; flight control would know it to another level; and operational; and then you had the engineering folks that might know the nuts and bolts on how the thing was made at a different level. So all those folks had to work together whenever you had an issue during the mission to try to resolve a problem.

Host:So was there anything that changed over your 12-year time of working as a system instructor? Did things improve? Did you sort of change or tweak maybe procedures as you were going along or maybe the technology improved?

Jeff Fox:Well, you know, there was one upgrade in the Shuttle, although I didn’t work it directly. We had a lot of column steam gauges, you know, on the forward panel. You know, if you know what the ADI or the eight ball is on there, it was a mechanical instrument, you know, expensive, calibrated, got to be maintained, have a certain amount of them. Well, that could be replicated digitally as well. So there was an upgrade made that allowed us to digitally replicate that. That was a good thing. So that was something that was done right in the cockpit. That was done across a number of displays that the crew could look at on the forward console. So it took the place of other steam gauges, ADI’s, tapes, meters, things like that. So that was a physical improvement you could see. It was probably more of maybe a high cost to put in, but hopefully maintaining it was lower. I never was close to the numbers on that.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:But the procedures, you know, we would update those and we found problems. That was a continual thing, you know? You’re always trying to stay ahead. Or your mission had something unique, so you’re changing procedures or putting them in real time or training on them before the mission.

Host:So let’s jump ahead now to taking some of these lessons, some of these — your work instructing astronauts to work these systems. Let’s jump ahead now to Orion and go back to these three screens that are kind of split from top to bottom. And what has changed with all of these procedures of flipping all these knobs that are all within eyeshot, looking at these screens? Now what’s the new setup for this new vehicle?

Jeff Fox:Okay, so unlike Shuttle, which we mentioned how many physical control points they had —

Host:Yes.

Jeff Fox:— think of more along the lines of 60, 70 switches on a forward panel. There might be a handful somewhere else in the vehicle. And the waste control system area or lights are different, com or data little ports, but the majority are in front of you on the panel by these three pieces of glass the displays are on. But the majority of those 67 switches, I’d say, they’re either used off nominally if there’s a problem, or maybe post-splashdown, or that type of thing. They’re not routinely thrown. So there’s a lot of control points, though, in all these systems on the Orion spacecraft. You know, they sill have cooling loops, and communication systems, and all these things that were represented by a hard switch for the most part on the Shuttle are now a software blip on a screen that’s under that piece of glass that we talked about. So you have to design these displays to throw these switches in the software whereas you could reach and grab a physical switch on the Shuttle before.

Host:If you’ve ever seen a Shuttle cockpit, actually, they have — I think it’s a 360 photo somewhere on the Internet. I forget exactly where. But you can basically look around and the whole thing was just filled with switches — up, left, right, right in front — everywhere is just switches. So now you’re talking about constraining all of these different things, all of these different components into these three screens; how do you fit everything?

Jeff Fox:Yep, a great question. Orion doesn’t have all of the subsystems that Shuttle had, but they still have a lot. And you still got to get that stuff on a software display.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:So the challenge is not only are all those switches under the glass in a software screen, but all of the procedures — that couple pounds of flight data file — roughly we’re working with maybe half a pound of procedures. And that’s what happens if my computer goes down, I lose my screen, how do I reboot it? Because that’s how you got to get access to all these different ways to turn a pump on or off, or an engine, or whatever it is. So that is different, you know? You don’t have to carry around all the switches and all the wiring, so you save weight, maybe you save some costs there. But the flipside is you got to put all those control points under a software screen. And you don’t have the real estate in front of you. And if you’re sitting there listening, just take three sheets of paper, put them 8.5 by 11 in front of you with about four to six inches between them, and imagine you got to put all this stuff for all these systems under there. It’s very challenging. So all the work that we’ve been doing is how do you get access to that stuff, including all your procedures, all your little switch throws, everything you got to do in that little amount of real estate?

That’s a tough challenge. Now, we’ve been very successful in doing that. We got great feedback from the crew. It’s just different. I mean, there’s certain things that were easier when you had a piece of paper in front of you and you could look at the procedure and grab over and throw the switch. But now I have to go into menu on this screen on Orion, I have to select something and drop it down and open up a display. Well, we thought about that, we can’t embed things so deeply in a menu that — in a critical situation you got to find it now. So we’ve had to be very creative with some auxiliary or other controls that are in your hand that might allow you shortcuts to get to certain displays. So there’s things that we’ve instituted and tried over and over in different evaluations with the crew and simulations that are telling us we’ve got the right system, we’re on the right track.

Host:Well, I guess put me in the seat of the Orion now. Because if I was in the Shuttle, I would have all of these switches around me. But now I only have a few things I can interact with and then a few different options for what I could be looking at, at the same time. So I guess we’ll start with what buttons can I press?

Jeff Fox:Okay. So around each of these 8.5 by 11 pieces of glass are several collection of edge keys or bezel keys. You know, if you look at some things like an F-18 or something like that, a cockpit, you’ll see buttons around there. Well, that’s one way you can press around the perimeter of that glass to interface with data under the glass.

Host:Okay.

Jeff Fox:But let’s say I’m strapped in for launch and I’m in a suit. And I got these three pieces of glass, I’m laying on my back, these things are above me. Visualize yourself doing that. And now I got to push one of these buttons. Say it’s in the screen that’s kind of in the center between me and the other guy, all right, and I got to reach for it. But my arms aren’t that long, let’s say, and I can’t reach that button in the center of the screen on the top. How am I going to get to that? I got to do something with it. So we created something called a cursor control device, CCD for short. That goes in your left hand. It’s like a mouse, but it doesn’t move, you know? It physically stays fixed. So that allows us — when we can’t reach the key around the display, we can use that thing to interface inside of the display. You kind of tab around with your thumb with a rocker switch and it moves you very quickly over something. And you can enter, and stop, and press, and do things inside the screen.

Host:But you have to do that with a pressurized glove, right?

Jeff Fox:When we designed it, we did a lot of testing. It had to work, one, for a glove that I guess you called it vent press if nothing bad goes wrong. Slight press, you know, you’re suited with a glove on.

Host:Oh, yeah.

Jeff Fox:If all goes well and you don’t have a cabin leak, then the glove doesn’t get real hard.

Host:That’s right.

Jeff Fox:But if it gets hard, will it still work?

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:You know? And then if I take the glove off and I want to use it with a bare hand that I optimized so good for the glove that’s not comfortable for the bare hand? So we were thinking about all that stuff primarily for the glove. And we did things like take that cursor control device and put it in a glove box. We reduced the pressure in there. We put our hand in a glove, put it on the cursor devices. The glove swelled up, puffed up, simulating a leak in the cabin. And then we would use that and interface with a screen on the outside of the glove box to see how well is that working? What’s the fatigue, you know, if I use this a long time? And are these buttons in the right place? So that turned out to be a continual development of the shape and placement of these controls. But it works very well.

Host:It’s amazing how many different scenarios you have to think of. Because I was thinking about just the glove, but now you’re talking about the glove, a pressurized glove, and the bare hand. It’s got to work in all these different situations. So I guess you could say this cursor is very specially designed for exactly this scenario.

Jeff Fox:That’s exactly correct. Very specially designed.

Host:So you’re able to, I guess, control and go around. But I’m trying to imagine what am I controlling? Am I controlling a mouse on the screen? What am I doing?

Host:Good question. So with the cursor device, when you’re not pushing any buttons, you want to interact with these screens in front of you. So let’s take one of the screens. You’ve got two crew in the front of the cockpit, three screens. One of these screens is in front of the commander and the pilot. One is in the middle and is shared. Let’s take the one in front of the commander. Remember I mentioned that the screen is split in half horizontally. You got a top half and a bottom half.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:This cursor device, let’s say I got to get something inside of this screen, I’ve got to turn a pump off. How do I get in there? So there’s a switch on there called a castle switch that you can move. You can change your field of focus and where you can interact with that display. So first I got to be able to get to that display. So what we do is we put a menu at the top of the screen, let’s say. So first I got to be able to call up the right display so I can use that little castle switch, move it, get up to the menu, move around in there, select the thing I want, bring up a screen. Now I’m inside the screen. Now what do I do? Now the cursor is live inside the screen. And there’s a lot of little zones in there that are hot. They’re a green color by nature, so that means you know you can interact with them. So now I can use this little rocker switch. I can move around and land on the thing I want. I hit the enter button on one of those things. Well, then what happens? Then I get a little pop-up window. And that tells you what you can do to that element — turn it on, turn it off, manual, auto, whatever it is.

Enable, inhibit. And I can move around in there and do something to it. I can change the state of it. And I do that with that cursor control device.

Host:All electronically, right?

Jeff Fox:All electronically, yes.

Host:So I guess if you’re looking at your systems, where are your procedures? Because I guess do you have the ability to have a book on your lap like you were talking about for Shuttle?

Jeff Fox:No, you don’t. Because all those displays — excuse me, all those procedures are now also under the glass.

Host:Oh.

Jeff Fox:So you have to share the real estate with not only your systems display, but your procedures and, you know, electronically. We call it EPROC for short — electronic procedures. And you might have hundreds and hundreds of those just like you had on the Shuttle. You can’t look at all those at once, so you bring up a screen that has a menu and says, “You want to go to what system?” I want to go to the guidance navigation and control section, okay? Open that up. There’s 50, 75 procedures in there. And you either get a caution warning message that pops up, tells you which one to go to or the ground might call and tell you go to that one. You click on it, you can open it. Bam, that procedure will pop up. And it may write over something that’s on the screen before. That just means you have to — the way you manipulate the data on the screen, you don’t want to stomp on something that you already have. So you have to be able to reorganize your layout, maybe move it to that center screen, something you were just monitoring.

So I can work a procedure on something that’s a problem on the screen in front of me. So you are learning to work with that screen management or display management, if you will.

Host:Yeah, that’s right. Because you can only have so many things on at one time and in your view. But I love that idea if there’s a caution or warning signal or some kind of pop-up, you can just click on the pop-up and say, “Okay, bring me to the procedure that is going to fix this problem,” or something. Is that what you were talking about?

Jeff Fox:You could. When you open it, there’s a way — you look your messages. We do have some improved ways of looking at the messages. You know, before they just came up by time on the Shuttle. You got an error message and maybe it said time or just came up in time. Now we can sort those by criticality. So let’s say a warning might be red and a caution might be yellow. Well, warning, I want to do something about the warning. It’s red, it’s bad. That’s what I want to do something about first.

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:So but right now I got reds and yellows all over the place. So I can sort the type of message it is. So I put all the red ones on top. And I may even be able to sort the red inside the group of red to tell me what’s the most important. I’ll give you an example. Let’s say an electrical bus fails. That might generate five or more red messages. Because one, the bus failed, but a whole bunch of equipment failed behind it. So I’m getting all these messages for equipment fail. But it’s not really an equipment fail, it’s a bus fail. So maybe if I was smart on the ground and I was able in software to prioritize those messages, I would say, “Hey, be smart enough to recognize that that’s this bus and put that at the top.” And so I’ll work that. And so I can send that procedure to an open set of procedures and open that display and have it call up the correct systems display, the correct text. It tells me what to do and compare data or answer questions yes or no. And it will walk me through all that. So there’s two interesting modes to the electronic procedures that’s really at the heart of the cockpit.

You can always do everything manually. Like we talked about before, the cursor device or the bezel keys, you can punch buttons, you can get inside of display, you can change the state of something manually. You always want to protect for that. If the ground called you and said, “Hey, we need you to throw this switch or turn this redundant com system on or off” I can just go to that; I don’t need a whole procedure for that. So I want to be able to do that. But there’s something called a guided mode with these electronic procedures that is smart enough that it will take you through them automatically. When you work a procedure, it doesn’t mean you’re going to be looking at just one display. You may be looking at several systems’ displays. Well, I don’t want have to go call them up manually and figure out where to go in there or look at the procedure and figure out what data they want me to compare and where it is on the screen. Well, electronic procedures in the guided mode will walk you through all that automated. So let’s say I answer a question about is the Freon pump on?

So it is smart enough that it will call the Freon pump display with all the data about the Freon pump up for you in addition to the text of the procedure. And then you just say, you know, “Yes, it’s on.” And then it will automatically go to the next step and procedure. And let’s say the next step is it wants you to look at something in the air system, the environmental — the pressurized air system. It will automatically call that up for you. You don’t have to call that up. It will put the cursor in the zone for let’s say the cabin pressure. And it will just say, “Hey, is it above 13 PSI?” It will just ask you a question, yes or no. You answer yes, boom, that one’s down. The procedure will index down another line all by itself. So the workload is much reduced. We actually did a study a while back to see how many — how much workload you would save manually punching buttons over the computer in EPOC guided mode helping you. And there was about ten to one in the number of manual switch throws you would have to do versus having the system guide you through it.

Host:And I guess it proved to be more further.

Jeff Fox:It’s much more efficient. It’s really at the heart of the cockpit. If you had to do all that manually, you know, manually call up displays, manually go up and check nominal data, as well as off-nominal data because some of it will be underneath, it would be an information juggling challenge. So you need some aids to help you do that. And that’s what’s designed in to several parts of the display and control system to help you manage that information.

Host:Man, I feel like — I don’t want to push it, but I feel like that could be something that I could do [Laughs].

Jeff Fox:You can and —

Host:If I got up to guided controls and they were just pointing me, “Hey, is the Freon pump” — and then it shows you Freon pump on, okay. Yeah, check.

Jeff Fox:It’s a little difficult to articulate, you know, in words because you’re not seeing it. And if you saw it —

Host:Yeah.

Jeff Fox:I could take you in there with very little knowledge about Orion or any cockpit, and in about two hours I bet you would be — feel very comfortable with 80% of the whole interface, from the cursor devices to the bezel keys, to the electronic procedures. You’d say, “That just flows very natural.” The buttons are in the right place, the logic, the way you pull the displays up and the menu. It’s easy. If I need to find something, I can get to it. And you can feel pretty confident. Now, there’s that other let’s say 10% to 20% that you have to design all these corner cases you call it where if we had to do it, we could. But I better practice those some more because I might forget those because I don’t use them very often.

Host:That’s right.

Jeff Fox:And that’s the case, too. But I tell you, we do a lot of evals, we bring in subjects for other human test program things that are outside the RPL that use a variance of this. And they bring in people that are not pilots that do this or similar type of things. We bring in crew, of course. We also are bringing in Navy and Air Force test pilots from the test pilot schools, you know, from Pax River and Edwards Air Force Base. And now they’re a different group, obviously. They’re used to cockpits. But the benefit we get out of them is they see all kinds of new systems that are out there. They can maybe bring something to the knowledge pool of what we’ve already done or recommend something. And we — you know, we have leveraged off their recommendations in the past.

Host:That’s great. You’re getting a lot of feedback from all different areas to make it easy but also kind of intuitive and appropriate for the folks who are going to be flying it. Have you actually sat down with a, I guess, former Shuttle pilot who has seen both ends, the Shuttle and the Orion, and maybe give any feedback there?

Jeff Fox:We’ve had a number of them. We’ve had, you know, anywhere from mission specialists to a couple front seat, you know, pilot commander types. And we’ve really gotten good feedback. I mean, the first time you see it, it’s a little — like anything new, how do I operate this?

Host:Yeah, this is so new.

Jeff Fox:But once you get into it, you know, we do our Orion cockpit 101, I tell you, I can take anybody that’s listening to this broadcast that could get in there and they would feel pretty comfortable. Now, would they retain that two weeks from now? Maybe 50%. But I tell you, if you use it on a daily basis, it’s very comfortable.

Host:I’m guessing you’re pretty efficient at it now, right now.

Jeff Fox:Pretty. You know, some of those corner cases I need to go brush up on. You know? If somebody asked me, I might have to ask the real experts, you know, that actually created it. But anyway, yes, we are very confident. We are actually using it in some mini-integrated simulations where we bring in the flight controllers, flight directors, CAPCOM types. We have a little room up in our lab that we have audio that we can send to our crew station with the crew and the flight control. We can introduce some malfunctions. And we can test not only what is it like for the crew to use this system by itself, but what happens when the flight control guys are trying to talk to you? And this is the first time they got exposure to this system. How clumsy or how good is that, you know? So what are we doing well and is there things we can improve on.

Host:So what are some of the next steps that you have to through to make sure that this thing is ready to fly?

Jeff Fox:Well, you know, we’re pretty far along in a number of years. We’ve got about 70 crew displays that we have to prototype. The RPL’s main charter is to prototype these 70 displays that the crew will use to monitor and control the spacecraft. Also, write the documents — we call them as-built documents — that describes how that system will work in great detail. When you read that, you have a very good feel — lots of screen snapshots for how you use it. So we are in the middle of prototyping all those displays. You know, maybe we’re half-done but we have half to go. So it’s a lot of work. It’s a small lab. You know, we’ve got a lot of really talented people wearing a lot of hats. You know, we’ve got to create these documents, and build these prototypes, get the crew in front of them. That product is, you know, a critical in-line product to the program. And it represents, you know, the crew’s interface.

Host:That sounds like a lot of work, man. Not only do you have to design the interfaces and all these screens, you have to write the manual for it.

Jeff Fox:That’s one of the — believe it or not, that is one of the most challenging things on this project. Because, you know, NASA’s used to reviewing stuff. If you sends them something to review in paper, they’ll look at it, you know? And so we’ve got a lot of these things going on. We have teams of folks, you know, engineers, flight controllers, systems experts all together helping design this. And then we put these screens together, we have a lot of technical reviews. They come out in this document. And then we receive feedback. And then when we’re happy, that can move forward and be accepted through the software boards and that type of thing.

Host:So let’s kind of wrap up with taking this technology that you guys are developing, these screens and these procedures, and having all of this feedback to create this beautiful set of procedures and technology; is there anywhere that it can be applied? It seems very specialized, but is there anything that it can be applied to on earth or maybe on future missions, or any kind of technology transfer there?

Jeff Fox:Interesting you say that because the generic part of the software — there’s a couple components on it. When I say generic, I mean the public affairs stuff that we can send out, there is a version of it that’s available to folks. Then there’s another piece of that with our displays that are more proprietary. We have made it available and several entities have picked up, they wanted to study it and look at it. And when we built it, we actually were soliciting and looking at the designs of a lot of different things from, you know, a submarine to military aircraft, civilian aircraft, you know, even the Airbus, a nuclear power plant. How are people managing critical information? You know? And what is the design we need, what can we leverage to make it do that and more? Because we’ve got a very complex set of tasks. Everything from the more mundane on orbit to, you know, the criticality of a launch or landing.

Host:Yeah, seems like some seriously complicated work. But it seems like you’re really trucking through it. And really appreciate it. So Jeff, thank you so much for coming on and explaining what you do and this work going into the spacecraft displays that are actually going to fly on future missions. Really appreciate you describing that and coming on the podcast again. Thanks so much.

Jeff Fox:Appreciate the opportunity, thank you.

[ Music ]

Host:Hey. Thanks for sticking around. So today we talked once again with Mr. Jeff Fox, and he gave us a little tour of the spacecraft displays that are going to be in Orion and then also a little bit of history on what happened during the Shuttle days and how that sort of transitioned to some of the logic behind the system displays for the Orion. So if you want to know more specifically about Orion, NASA.gov slash — guess what — Orion. Yes, that’s where you can find some of the latest and greatest about that vehicle. Otherwise you can go on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter and see the latest and greatest there. On Facebook it’s NASA Orion; Twitter is @NASA_Orion; and Instagram is @ExploreNASA. That one actually has Orion and the space launch system, which we talked about a couple episodes ago. You can use the #AskNASA — there it is — on any one of those platforms to ask a question about Orion or you can go to the NASA Johnson Space Center accounts on any one of those platforms and submit a question for Houston, We Have a Podcast. We might bring it on one of the future episodes or make a whole episode out of it, which we’ve actually done a couple times. So this podcast was recorded on March 21st, 2018. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Greg Wiseman, Tommy Gerczak, Rachel Craft, Laura Rochon, Brandi Dean, Pat Ryan, Bill Stafford, and Kelly Humphries.

A lot of people to thank for this one. And thanks again to Jeff Fox for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.