“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

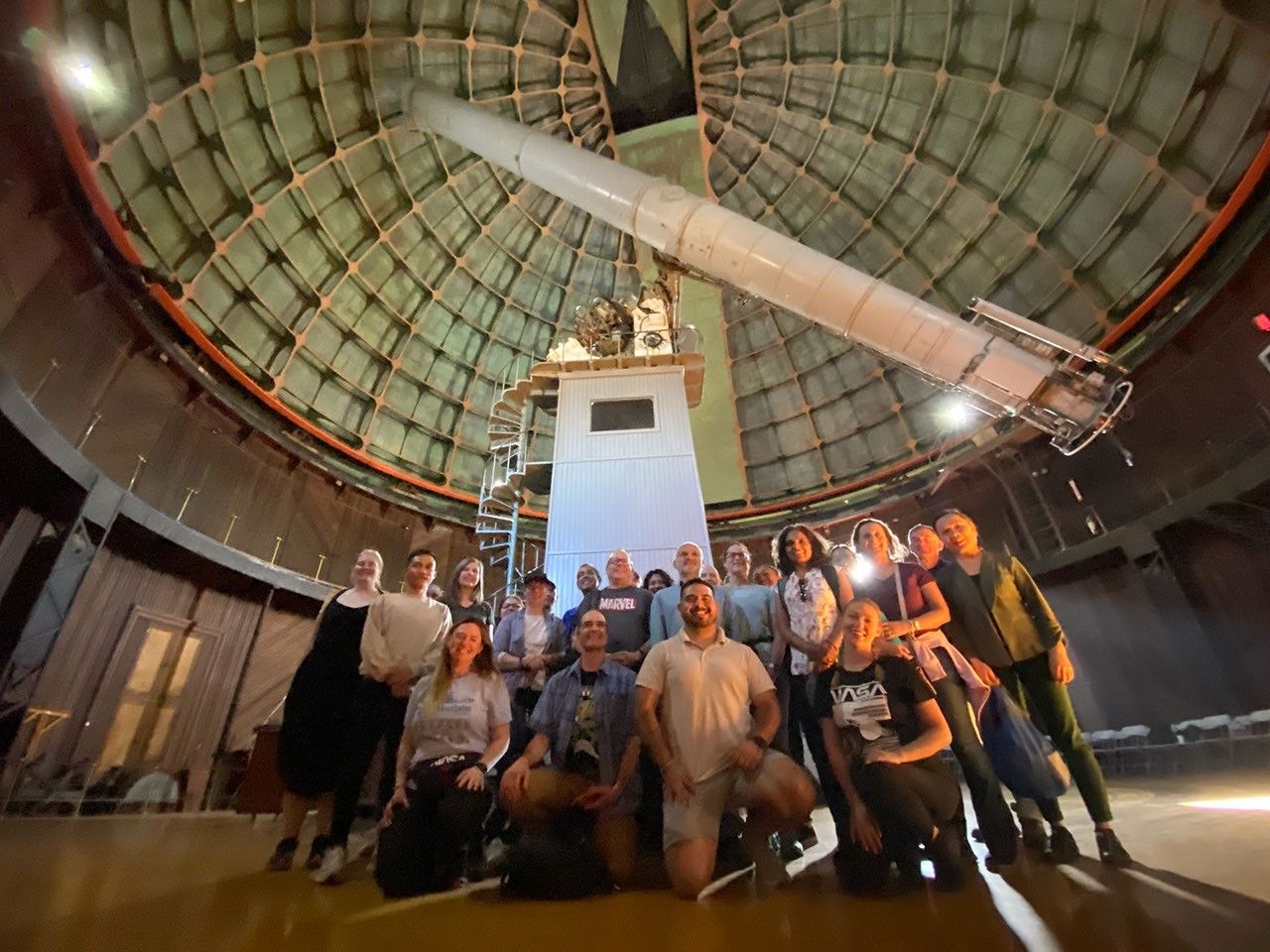

On NASA’s 60th Anniversary, Houston, We Have a Podcast takes the stage for Episode 67 with science fiction writers Mary Robinette Kowal, Dan Wells, Howard Tayler, and publishing agent DongWon Song, as well as NASA astronaut Kjell Lindgren to discuss how real science and science fiction have influenced each other. This episode was recorded on October 1, 2018.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host):Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 67, NASA’s 60th Anniversary Live. I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. So if you’re new to the show, we bring in experts to talk about all the different parts about our space agency. Now, recently we just celebrated NASA’s 60th anniversary, and we celebrated on October 1st. We accomplished a lot during those years, and you can even humbly say that NASA changed the course of human history and inspired generations. And we did something special to reflect on this very idea. We took “Houston We Have a Podcast” on stage for our folks here at the Johnson Space Center and brought in special guests from the podcast Writing Excuses. We’ve sat down with science fiction and fantasy writers Mary Robinette Kowal, Dan Wells, Howard Taylor, and special guest DongWon Song. Mary, Dan, and Howard have written science fiction books, many of which are set in space. And DongWon is an editor and a literary agent. We discussed how 60 years of NASA has influenced works in fiction and even how fiction has influenced real science and innovation.

We also sat down with NASA astronaut Kjell Lindgren — who flew back in 2015, has accumulated 141 days in space — and he gave somewhat of a NASA perspective of things. So with no further delay, let’s jump right ahead to our first recording of “Houston We Have a Podcast” from the stage for a live audience to celebrate the 60th anniversary of NASA. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host: Hello, everybody, and welcome to the first live recording of “Houston We Have a Podcast,” for the 60th anniversary of NASA!

[ Applause ]

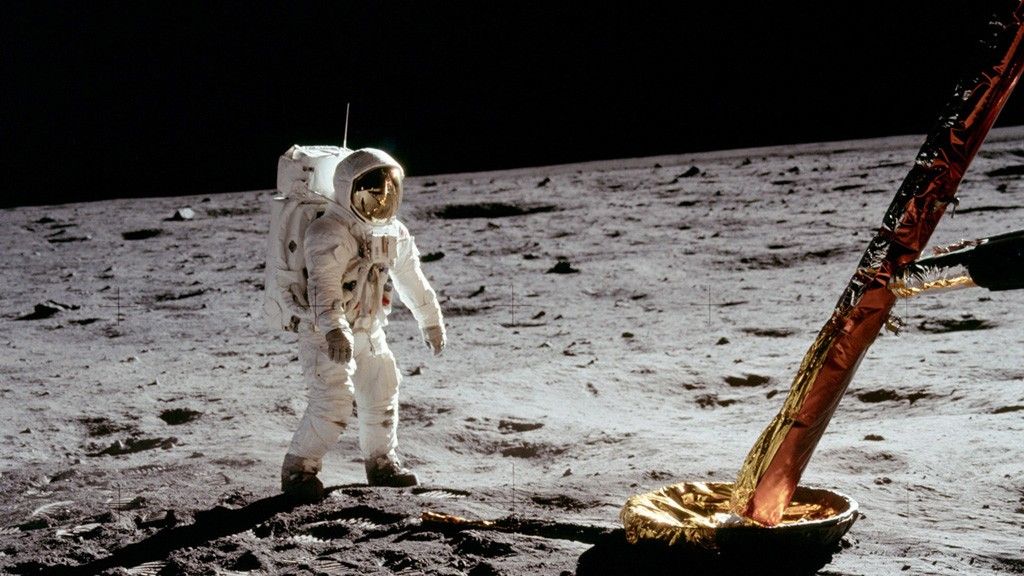

Host: Wonderful, wonderful. All right, Michelle in the back is going to give you your payment, so thank you for that. [laughter] All right, so like I said, today, October 1, is 60 years since NASA first opened its doors. Think about all the history that’s happened over 60 years. We’ve seen the first humans fly in space. We landed on the Moon. Now we’re talking about continuous habitation above our heads. Anyone — I mean, how many times have we spit out the statistic, anyone born after November 2, 2000, has never known a time when people have not been in space. And we get to say that now because of 60 years of constant discovery, including not just human space flight. You know, how many times have we talked about the Hubble deep field image, how many galaxies and how many stars are in the universe? More stars in the universe than there are grains of sand on Earth. It’s pretty insane. But if you think about it, I mean, I personally am here and I’m sure many of you are here because you were inspired one way or another to come work here through something, whether it was something that we did at NASA or some TV show or book.

I mean, how many of you here are Trekkies, right? Exactly. I mean, you drew up with Star Trek and you were inspired. Maybe, oh, my gosh, this is so fascinating, exploration and discovery. I want to do that for the rest of my life. Where can I do that? NASA, right? It’s part of our culture. And so to do 60 years of NASA, to mark this momentous event, I wanted to do something special for Houston We Have a Podcast, so I have a very special guest next to me. They host the podcast Writing Excuses. They’re all literary authors, and we also have a few extra special guests. Starting to my right, Dan Wells, science fiction author. DongWon Song, who is in publishing, an editor, right? Mary Robinette Kowal. Howard Taylor. And of course, many of you know, Kjell Lindgren, NASA astronaut. We’re going to bring the whole perspective together. So thank you all for being here today. I wanted to start because on this idea of inspiration. Because we, a lot of us here, were inspired to work here at NASA because of maybe something, some TV show or a book we read.

Now we’re talking about a time — I mean, how many space movies have come out? Many of you are writing books that take place in space and in the future and all these kinds of concepts. Mary Robinette, I wanted to start with you. What inspired you to write science fiction to talk about space in your literary works?

Mary Robinette Kowal: So there’s two factors. One is that I looked at the requirements to be an astronaut and just that was never going to happen. [laughter] But more specifically, I was born in 1969. And my parents tell the story about how I could sit up to watch Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin by myself. I could sit by myself, they’re very proud of that. But this narrative of, you know, you set up to watch us put people on the Moon for the very first time was part of my childhood. And that just sparked I think a lifelong fascination with space. I remember watching the very first Challenger launch and being amazed that we were putting people in — I’m going to geek all over the place to people who totally know this stuff. But the fact that we were launching a maiden, an untried vessel with people in it was just amazing to me. And then Sally Ride. And it was like all of these things. So basically I write science fiction because it allows me to explore all of those things without actually having to do the work of the science.

[laughter]

Host: I feel ya, definitely. Because even me, like I can’t tell you how to build a rocket. I can’t tell you all the different things that go into astronaut training, that’s why Kjell’s here. But I do love communicating. It’s so fascinating the idea of exploration.

Howard Tayler: One of my very earliest memories is a little tiny black-and-white TV on which there is a man in a spacesuit walking on the Moon. 1972 probably would’ve made me, you know, four or five years old. So Apollo 16 or 17, I don’t remember any of that. I just remember there’s a man walking on the Moon and my parents explaining to me how incredibly amazing and important that was. And I grew up in a world in which, yes, it was amazing and important and exceptional and incredible and all of these other things. But it was also just a part of the natural law. We walk on other planets. That was the society that I grew up in. And it’s the society that when I write, when I draw comics, that’s what I want to share. I want to tell stories about societies that exist across other planets.

Dan Wells: You mentioned earlier Star Trek. And one of the things that continually delights me is, you look at Siri and Alexa and Google Home, all three project leads on all three of the major voice assistant AI’s have specifically said in interviews that they are doing it because of the computer on Star Trek, that that’s what they were inspired by and that they are very specifically trying to re-create that. And the ability of science fiction and literature and art to influence the progress of human technology and of advancements that we can do is incredible to me.

Host: Yeah. And it kind of goes back to Howard and Mary Robinette’s point. It inspires each other, right. So there’s the science fiction element that inspires real life technology. And then you were inspired to actually write science fiction based on real stuff that was happening in the world.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Yeah. So I’m going to talk about one thing about the back and forth, that particular thing. So one of the things that’s really fantastic about the computers on Star Trek is that the woman’s voice. That is something that there’s this interesting correlation. In the United States, women’s voices tend to be the voices of computers. And when you look back in the history of spaceflight, and the history of computing, the computers were women. For anyone who’s seen Hidden Figures who are well aware of that. But in the early days, there would be a woman sitting in the launch room and she would be calling out. They said, computer, tell us the trajectory, and so that voice became the voice of computers. In Germany, the computer voices tend to be male. And when you look back in their history of spaceflight, the computers, the people who were doing the math, were men. So it’s this interesting back and forth where real computers, real women, influenced why the sound of that voice needed to be a woman in order to sound right to people who were in the sciences at that time.

And then now we’re like, well, the computer on Star Trek, which what sounded like a woman, so now we need to make these actual computers, you know, these AI, we need to make those — so it’s this interesting back and forth where we feed creativity to each other

Host: Yeah. It’s almost like, even though it’s, you know, science fiction, that’s what’s normal to you. That’s what kind of feels right.

Howard Tayler: Well, one thing that’s really interesting and important to me is this idea that, even though science fiction can often be about distant futures and all these different elements, we’re still always telling stories about us. The stories that we tell are very grounded in the present. Science fiction isn’t necessarily predictive. It’s a way for us to really understand the world that we live in and the society that we engage with. So for me growing up — I grew up in South Florida, a couple hours away from Cape Canaveral. So whenever there was a shuttle launch or any kind of rocket lunch, we would gather on the football field and stand there and watch that go up. And it made space and technology and, you know, what we talk about as science fiction very real to me, right. It was very tangible. It was very grounded. Which is an ironic word choice. But, you know, seeing all that happen in front of me in a space where I could stand and actually see the product of it made it very real. And so when it came for me to enter the industry, it then felt very natural for me to be working in this area where science fiction is so much the way in which the metaphor for me engages with the world around us.

And so hearing about how the computers on the spaceships are tied to the humans who were performing that role is just a beautiful reflection of that idea for me.

Host: Yeah. Now, DongWon, in the publishing world, do you find that there is more of a push even now for more stories about space, more stories about technology, about the future? Are you seeing that shift?

DongWon Song: Space always has a sort of everlasting appeal, right. There’s an evergreen nature to, we love stories about space, we love stories that happen in distant galaxies with spaceships and all that. And you know, sometimes that can be very distant and a very Star Wars kind of space magic. And that’s not really about space in a lot of ways. It just happens to take place there. So it’s really exciting that we’ve seen a shift in the past few years of stuff that once again feels more grounded in the kind of space exploration that we’re doing now or, you know, that we can engage in in the next few years, whether that’s Mary Robinette’s books, Calculating Stars, or whether, you know, that’s something like Interstellar or The Martian, right. These are things that feel really grounded to the world that we live in and sort of reflect our ability to imagine even when it’s very fantastical ways in which we could actually get there and ways in which we can actually experience spaceflight and living on other planets.

Dan Wells: Yeah. I want to talk about The Martian as well very quickly. Art and science fiction, you know, it always moves in cycles. And we are kind of clawing our way out of this very depressed era that we’ve been in. Depressed might be the wrong word. But we’ve had very dark fiction. We’ve gone through the big wave of dystopias, which were very huge. And what we’re starting to see now is more stuff like The Martian, where it is getting back to that — you can talk about Star Trek again — that original idea of, here is our — the science fiction stories we are starting to tell more and more frequently are hopeful stories about everyone coming together and using science to solve problems. That’s what The Martian is. That’s what Mary Robinette’s series is, The Faded Sky and Calculating Stars. We’re starting to see so much more of that and it’s really part of a big thing.

Host: So do you think — you talked about the dystopian. I’ve seen a lot of those movies, read a lot of those books. It was part of that. Now you’re talking about the shift towards something more collaborative. Is it because of stuff going on around the world? Why do you find that this need is now coming up?

DongWon Song: Well, one thing I think is really interesting — like I said earlier, science fiction is often about the world around us. And the questions that are really interesting to me when we tell stories that are science fictional are — they’re fundamentally about people, right, and how do people live in these worlds, how do people engage in these worlds? And The Expanse is a series of books that I was very lucky to work on early in my career. And one of the reasons I have such love for that series even now as it continues to go on and is on television, is it shows ways in which our current 2018 society, the global politics and the dynamics between different groups, can influence the futures that we live in. It feels very textured and very grounded in the ways in which, you know, certain groups will still be oppressed, there will still being inequality, there will still be all these things in the future but yet political — our ability to imagine better political futures will also be true then too, right. We can imagine collaborative solutions. We can imagine cooperation. We can also imagine violence and we can also imagine oppression. And when you combine all those things, then you have what to me is a truly profound story about our ability to build a better future for ourselves.

Howard Tayler: Fundamentally what I write is social satire. I’m a humorists. Schlock Mercenary is a comic strip. I am engaging the reader with things that’s that they’re familiar with and I’m using science, I’m using space and spacecraft, and the Fermi paradox and all of this as a setting in which I’m able to look at how the ideas, the concepts, the beliefs, the cultures that we have today would map onto a world in which the background is a lot different. As DongWon said, science fiction isn’t, you know, always predictive. I desperately hope that what I’m writing is not predictive. And one of the first laws of my universe is that there’s always going to be a punch line, and that’s a terrible place to live. [laughter] But I’m also very, very optimistic, because I love — I like people. I like laughing. I like the belief that while science can’t solve our problems, science and the sharing of information can help us understand our problems so that we can change and we can become better.

Host: What’s interesting about what you just said was that, you know, you build these characters and you build this environment and this universe around stuff that you understand. And things that while we’re discovering them, you know, we communicate to the public and say there is this thing called a Fermi paradox, there is this concept of that universe expanding over time. And you can develop a story around this world. But it’s not something that you just invent, it’s something that you understand and like, wow, that’s fascinating. I want to invent something around that.

Howard Tayler: I watched — I don’t know how many episodes there are of PBS’s Space Time, but I watched a lot of them. Space Time diagrams, quantum electrodynamics, Feynman diagrams, things that I still don’t understand but I love. And all of it informs the stuff that I will be writing in the future.

Mary Robinette Kowal: One of the questions we get all the time is: Where do you get your ideas? And for me the question is formulated in a way that is not useful. Because the ideas are there all the time. It’s how do you get from an idea to a story. And so one of the things that I think, you know, when you’re talking about the Fermi paradox or, you know, watching launches or things like that, that what we do is fundamentally something that I think science does, which is to say, what if? You know, what if this happens in this way? What are the consequences of this? We spend a lot of time as science fiction writers going, what can go wrong? Which y’all at NASA do very — a lot of that. You come up with contingencies that work, we don’t. That’s not what science fiction writers do. We just look at how it can go even worse wrong. But the ideas are all there. And so like listening to “Houston We Have a Podcast” is incredibly useful for me, because of it’s just filled with ideas.

And talking to Kjell is another place that I pick up a lot of my ideas. It’s like when he talks about what happens to the — he was at the Nebula Awards at a banquet for all of these people, and all of this room full of science fiction and fantasy writers, and he gives a speech about what happens to your body in space, which includes the calluses that come off the bottom of your feet.

Kjell Lindgren: And I do this during dinner too. But fair warning. I let everybody know if they had a foot thing that they should stop listening. [laughter] You know, I think the idea that the ideas are out there does you all a little bit of a disservice though. Because certainly the ideas are out there, the staging for the stories that you all tell. But it is the placement of the human experience in there and the framing around the human experience and then the human perspective that makes these stories and these movies so enjoyable. Because it really helps I think the reader or the participant experience it as almost a first person or a participant. And I think that is the real joy of reading or watching science fiction and the translating of dry science or situations into something that is exciting and inspirational.

You know, I would say that I know that science fiction, both movies and the written, were absolutely fundamental to me doing this job. You know, I’ve wanted to be an astronaut for as long as I can remember. In fact, I know that two foundational books for me were Saber Jet Ace by Charles Coombs, which was a description of Joseph McConnell. He was an F-86 pilot in the Korean War. And then Runaway Robot, which was a little kid and this robot on Ganymede. And I have pictures of those covers in my head. And you know, I wanted to be a fighter pilot. I wanted to be an astronaut. And did I think that I would have a robot when I was a little kid on Ganymede? Certainly not. But this idea of living and working in that setting and pursuing an opportunity like this and being constantly inspired by science fiction and what the possibilities were.

And certainly many of the books I read, I’m glad that we are not in those situations. But exploring the ideas around that. Exploring the responsibilities that we have and the use of technology. You know, with Asimov’s rules, the directives for robots, all those things are just really amazing thought experiments. And to get to participate in those in a small way now with our space station expeditions and with the amazing team that we have here at JSC and around the world is a phenomenal thing.

Mary Robinette Kowal: When you talk about thought experiments, periodically we get invited individually or as a group to go and be futurists at some event. Which is term that people use when they don’t want to admit that they’re talking to a science fiction writer. I’m a futurist. And so I was at this one for — at a museum that was dealing with science and industry, and they were talking about revitalizing and ways that they could do educational outreach. And they’re like, you know, one of the things that we could do at this museum is think about what it would be like to send a ship through space with over multiple generations. But no one’s thought about this. And I’m like, umm. So it’s called a Generation Ship. Here is a reading list of books. What we do in science fiction all the time are thought experiments about what is this going to be like. How is this going to be going down? And you’re right, it’s absolutely about the human experience. And that’s part of I think one of the things as well that I’ve been excited about seeing NASA do, is more of the narrative stuff.

I think that’s one of the reasons that everyone is so worried about opportunity is because there’s a personality there now. Even though this is a robot, there is a narrative. And humans are made of narrative. We latch onto it. We learn most efficiently through narrative. So it’s exciting to see those things going back and forth and communicating.

DongWon Song: You know, this point’s come up a couple times both from Mary Robinette and from Kjell, but this idea that science fiction helps imagine the consequence of technologies, right. And Mary Robinette pointed out that here at NASA, it’s imaging the disastrous consequences so you can prevent that happening. For science fiction, so much that is — what are the emotional consequences that’s happening, right? How is this technology going to make you feel? And it sounds very sort of wooly when I say it that way, but that gets to the root of why people do things. People are very reactive in an emotional way. So when somebody is abandoned on a planet and they have to survive for a year, not only how are they going to do that, but what is that going to do to them mentally? Why are they going to take the actions that they take? How is that going to feel? And I think that’s a really important thing in terms of how we can envision the futures we want to envision is not just, oh, hey, we could do this thing, but here’s the why of we’re going to do this thing. And here are the consequences of that for the people who are going to be involved.

Dan Wells: As the — I don’t know who said it first, but the line, “failure is not an option.” The degree of planning that goes into putting a group of people on a spacecraft for its virgin flight, for its maiden voyage, is astounding. Within the more human side of things, I’m all about subverting stuff. Failure is not an option. Failure is mandatory. The option is whether or not you let failure be the last thing you do. And I love learning from mistakes. I love that NASA tries to make as many mistakes as possible before there’s people sitting on top of a bomb. [laughter].

Host: That’s true, that’s true. That’s why we have these tests. You know, we were talking about just a couple years ago, EFT1, the launch of the vehicle that’s going to take people into deep space. We did it without people first. We wanted to test a couple things. We’re going to do it again without people first, because we have things to think about. One of the things you were talking about though is entering into the emotional state, to understand the series of events after something goes wrong to understand how to react to that. What do you as authors to enter into that space mentally? To really get into the mind of what would happen in the individual concept, in the societal concept? How do you get there?

Mary Robinette Kowal: You will hear a phrase a lot of times that “you write what you know.” And I think that what we’re doing a lot is that we’re extrapolating from what we know. So like I went to watch a dev run at the MBL, and I’m never going to get in the MBL pool. But I know I can — I know what going into water is like. I know from — because I’m a professional puppeteer, I know what really uncomfortable positions look like. When Kjell got out of the EMU, I was watching his hands and was like, the movements he’s doing are exactly the things that I do when a puppet is — the controls are overly stiff. It’s like I know what that feels like. So a lot of what we do is we wind up extrapolating. It’s like how would I feel in that situation? What is my lived experience? What aspect of that is tangential to this? And then the other thing we do is we look a lot at how people react through history.

There are very predictable ways that groups of people react. There’s cycles that we go through, that the way children interact with their parents. There’s a cycle that we go through where we venerate — in fashion, we venerate the natural world and we trend over into venerating the artificial world. And so children who have grown up with parents who venerated the artificial will push back by venerating the natural. Which is how you go from the information age into the local first thing. So knowing that when I’m looking at the future and I’m trying to extrapolate like what is this like on a space station that’s is permanently inhabited by generations of people, I have to — I think about those generational pushes and pulls. So it’s that kind of back-and-forth and thinking about patterns that I wind up doing a lot.

Dan Wells: I have just sold a new science fiction series, so new that it’s not even in any of your notes. It’s a middle-grade science fiction. The first book’s called Zero-G, and I’ve sold it to Audible. They’re making it one of their big flagships. And we’ve talked about how as science fiction writers, as writers in general, we love to focus on what goes wrong, right? Because conflict is such an important part of story. But I have found with this middle-grade series as I’ve been planning out the whole series of multiple books, that I keep coming back to the idea of, you know, first of all, there needs to be a problem so that we can solve it. But also where’s the fun, you know? Because I also, just like Kjell, I read those books when I was a kid about, you know, the Robot on Ganymede about the kid who lived in a deep sea base with his father and swam with a dolphin and things like that. And so I’m finding, you know, well, they’re going to go to this planet. What can I do to make that planet fun? And so, you know, altering the atmosphere, altering the gravity.

How can I play with physics to create a scenario where we can read the book and say, you know, I want to do this? I want to be a part of this. I want to go out and jump around and be able to jump over my own house and things like that. And so a lot of what we do to get into the, you know, the emotions and the mindset of our readers where we’re controlling your minds. That’s the secret of writers. [laughter] We’re deciding what emotions we want you to feel.

Mary Robinette Kowal: He’s not kidding.

Dan Wells: And obviously we need to do the research to make sure that our science is correct, and that we are accurately reflecting real experience. But we’re also specifically trying to create that mindset. We’re trying to inspire you, very specifically, to think and feel in a certain way.

Howard Tayler: A few years ago, we did an episode with — I’ve forgotten his name…

Cory Doctorow.

Did an episode with Cory Doctorow where we were talking about the neuroscience of fiction. The idea that when we tell ourselves stories, we can become more emotionally attached to these characters who only exist as fictional constructs. They exist as patterns of ink on a page, which we then turn into real people in our minds. And those people are more important to us than some actual real people in the world. It’s fascinating how that works. We try to only use our powers for good. I’m speaking only for those on stage.

Mary Robinette Kowal: He’s not speaking for me. [laughter].

Howard Tayler: But it’s fascinating. And so when I think about — you know, I’m writing social satire. I’m talking about the future. I’m talking about — talking about space travel. Talking about hope. Talking about despair. I’m talking to people who are going to internalize the things that I say. And I don’t want it to sound like I have some huge social responsibility to somehow make the world better. Mostly I just try to make the world laugh. But after talking with Cory and looking at the science of what it is that we do, I got a little worried, because it’s mind control.

DongWon Song: Yeah. I mean, one thing I like to talk about a lot when I’m talking about storytelling and craft is that, you know, humans are pattern-seeking creatures, right. The way our brains are wired, we seek out patterns in the world around us. And at some point I realize, oh, that’s just a story, right. When we talk about those patterns, we’re telling a story about other people. Mary Robinette mentioned we’re sort of narrative seeking and, you know, that also means we’re pattern seeking. And to me I realized that storytelling is how we communicate danger and nuance and complexity to the people around us, and specifically to future generations, right. So that’s how we transfer knowledge down from one generation to the next is by explaining the patterns that we run into. And that used to be that fire is hot and you shouldn’t put your hand in the fire. And now that is, look at the societies we could build if we imagined this one way of being. Or look at this how you navigate a romantic relationship. This is how you deal with your parents or raise children and all those things. That gets more complicated and more nuanced and more specific with each iteration.

And I think it’s a really beautiful thing that we get to do as a species.

Mary Robinette Kowal: One of the things that bounces through my head is — listening to you guys — that when I’m thinking about, do I have a responsibility. I have a responsibility to myself, because the stories that I build are part of creating the future that I want to live in. And knowing that it’s not just me that’s reading them. So in a lot of ways I am writing for myself, trying to build that future, but I’m also writing — even when I’m writing stuff for adults, I’m writing things for the person that I used to be who needed to read that book, who needed to read that book as the stepping stone to the future that I want to be in. So it’s entirely selfish.

Host: It’s an understanding of the world around you, but kind as a learning experience too, as you understand it now and how you want communicate it to yourself before.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Yeah. Dr. Z was talking about, when he was talking about the Parker solar probe — I got to go watch that launch. And Dr. Z said that there’s a difference — that sometimes you do science that is curiosity-driven and sometimes you do science that is practical, practically-driven. And I feel like a lot of what we do as science fiction writers is that we’re doing the curiosity-driven science as a thought experiment and hoping a lot of times that someone is going to come and do the practical work after that.

Kjell Lindgren: You know what’s really interesting to me listening to this — and I’ll describe the parallel that I see — is that, you know, we’re talking about science fiction, really the domain of starships and time travel and laser beams and all those things. But really it’s still all distilled down to the human experience and the human narrative, how we tell stories to provide lessons and warnings. And it’s one of the things that — my favorite things about working here at NASA is, you know, I think a lot of people when they think about NASA, think about the rocket ships and space stations and floating and all those things. But, you know, for me, I think one of the profound joys of working here is really the team, the people, that we get to work with. So it really still boils down to that human element. You know, the machinery is amazing, but it’s still just machinery. It’s aluminum and sterile surfaces and all those things. And so it’s the people that are putting those things together that run all of those tasks that have invested time and energy in making sure that these vehicles are safe, that they do what they’re supposed to do.

We get to interact with a few of those folks. In the astronaut office, we get to interact with a few of those folks as we train, as we’re operating the vehicle from orbit. But that is the joy. I mean, having this — being one small part of this larger team that gets to do these amazing things: to fly, to explore. And so, you know, that parallel of science fiction and really still the human element being the most important part in both science fiction and in the operation of spacecraft today is — I mean, I think that’s an interesting thing.

Host: I notice that about whenever we do in-flight events with the crew aboard the space station, we connect with schools, and we’ve been doing it for a while now. We’re in this year of education on station connecting with lots of schools. And they always ask questions about the experience. What’s it like being an astronaut? What’s it like to float? What’s it like to do this? And so, you know, you being an astronaut and understanding that, being inspired by science fiction or whatever, coming back and now being the person that’s communicating that, how do you do it?

Kjell Lindgren: You know, I mean, that’s a really interesting point. But I think fundamentally it comes back to the human experience. I mean, people want to understand like what was that like? And what would that be like for me if I were in that situation? I think it fundamentally answers the question of why we explore. Like why we sent people into the Earth orbit, why we sent people to the Moon, why we’re going back there, and why we’re going to send people to Mars and beyond. There’s always this age-old argument of, you know, we could send robots. And I always answer that with the same question of, why would you go to New Zealand? I mean, if you can see pictures of New Zealand, you know, if somebody sends you pictures as if there was a probe that went to New Zealand, or to the Sahara or to beautiful spots all over the globe, why would you go personally? It’s because of that human experience part. The next best thing is to talk with somebody that’s been there that can explain what the human experience is of seeing those things with their own eyes, of touching the sand or touching, you know, the trees or whatever.

That actual experience of being there. And so having the privilege of getting to communicate what it’s like to live in space, to be in Earth orbit for a long period of time. You know, that was my very favorite part of getting to fly, was getting to fly for a long duration. So that I truly got to learn what it was like to adapt to being without gravity and, you know, having to eat and sleep and work, use the bathroom, in that absence of gravity, and getting used to it so that it was a normal commonplace thing. That was what was really exciting about the long-duration mission, and then getting to share that with folks that are interested in communicating it in fiction. That are interested — you know, getting to talk with kids about it. All these just very human experiences but in a very different environment.

Host: I feel so selfish because I get to have this great conversation with you guys. But we have mics over here to the left and to the right. If you guys want to come up and ask a few questions, we’ll up it up for some Q&A. Just line up and we’ll kind of incorporate it into the show.

Howard Tayler: It was good of him to spring that on you right now so that you had no time to think about what you were going to ask. [laughter]. We do this to a lot of our guests as well.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Yeah. Just so you know, I am totally open to answering any questions about the writing process. You heard me say the word puppetry. I’m totally happy to go off topic there. Although I can actually talk about Apollo and marionettes, which is a real thing. It’s.

Host: Continue.

[laughter]

Mary Robinette Kowal: So Bill Baird was one of the top marionettes, he was the top marionette of his day. And CBS was afraid that the satellites — that the images from the Moon were going to fail. So they hired Bill Baird to create a replica of the Moon landing craft and the astronauts and filmed it.

Howard Tayler: I knew it!

Mary Robinette Kowal: And they used that for multiple — so for the actual Moon landing, they were fine, they showed that. But for several of the other — for several of the Mercury program space walks and for a couple of the — one of the Apollo missions, what went out over the air was actually marionettes. And there was a live studio audience as well. So there are people who — I think this is where that seed of, no, no, they did with marionettes. I think that there was someone who as a kid who actually saw that and didn’t understand that everyone knew that it was marionettes. Because it said at the bottom of the screen, you know, “this is a simulation.” Yeah. So actual marionettes. They still exist, the marionettes exist.

Host: Where? I want to find them.

Mary Robinette Kowal: I can give you that information. And there’s a picture of them in the book, Marketing the Moon. There’s a picture of one of those broadcasts. It’s the only existing picture. Someone took a picture of the screen, so there’s no footage of the broadcast, unfortunately, or fortunately, depending — because the Moon hoax people would just be all over that.

Host: So I’m guessing that — we’re going off of this topic of human.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Sorry.

Kjell Lindgren: Tangent.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Sorry about that.

Host: We’re talking about the human experience, but that kind of makes me think of research, right. You were talking about writing off what know. But how far do you go into researching and understand what you don’t know and then incorporating that into your story?

Howard Tayler: I am a big fan of the known knowns, the known unknowns, and the un-unknowns, the unknown unknowns model, because it means that I just have to listen and learn everything. Because I don’t know what — I don’t even know what questions to ask until I’ve started soaking things up. I am fortunate in that a good 60 to 70% of the time that I spend creating is not spent using the part of my brain that has to make words. I’m drawing pictures. And so, you know, when I said I plowed through, you know, three years of PBS’s Space Time, I did that while I was drawing. I was working. I was not sitting there doing research. I was sitting there letting research enter me while I got other work done. Which is probably why I need to watch it again, because I missed some of the important diagrams. I love that, because at the end of a drawing session, instead of just having, you know, a sore hand and a stack of comics, I have a sore hand and a stack of comics and a big list of questions that I get to go try and find answers to.

Dan Wells: One of my series that I’ve done is a post-apocalyptic YA trilogy where the apocalypse was a plague. So people got sick. And one of the big plot threads is, we need to cure this. And I realized as I was outlining, that I never wanted to write the sentence, “then she did some science and cured the plague,” you know. [laughter] And so I had to do so much research into medicine and biology and virology and how could this thing function and how could a scientist study it and get it wrong a couple of times and then figure out how to do it and then solve it. And that’s what I really love about science fiction. And that’s what shows up at some point in all of my books, is Dan did all this science — first of all, he wants to make sure you knew he did all this science. [laughter] But second, you know, finding ways to actually turn that into a story so that you can learn something about virology that’s super cool that I found while I was studying it.

DongWon Song: I find that there’s two kind of modes of research. One is the very active mode research, which Dan just described in terms of studying humanology or orbital mechanics or whatever it is. But then there’s a thing that I find really delightful as I get to spend a lot of time with writers — which is sort of passive research — and that is that thing that anytime you’re with a group of writers, at some point in the conversation will turn to, do you want to know what cool fact I just learned? And it just it’s like kids at a lunch table sitting around and just telling you about a weird thing they found out about an animal or a weird thing about space. Or just talking about cool stuff, and then that can be such fuel for your waiting or anything you want to put into your book, or even just the seed for a really amazing story idea.

Kjell Lindgren: You know, as a consumer of science fiction, I would say that when there is active research and the author is clearly done homework to at least present a plausible solution, I mean, that really comes through. And I really enjoy that. You know, we talked about The Martian a little bit earlier. So I read the book before I flew and we actually got to watch the movie on orbit, which was phenomenal. But it was clear that the author, that Andy Weir, did a lot of research and a lot of that made it into the book and made it realistic. I think, you know, it doesn’t always have to be realistic. But for me at least, there has to be rules. So if it’s, you know, future thinking and some neat gadget, it still has to have rules that surround it and it can’t be, you know, and then the box produced the solution for the problem, and you know, everybody was happy.

So I love the brainstorming and the futurism about science fiction and what could be. But, you know, as long as it still fits within the paradigm — the rules of that world, it’s fun. When it exceeds that, then you’re kind of like, well, that was a waste of time.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Yeah. I do a lot of the kind of layered research that Dan is talking about. But I also cheat a lot. So I’ll hit a scene, particularly in the Calculating Stars books, and I’ll write something that’s like, and then the captain said, jargon as he jargons the jargon. [laughter] And put it in square brackets and then I’ll email it to Kjell and say, can you play mad libs?

Host: See a little bit of help comes in. I think we have a question from the audience.

Audience Member: So Douglas Adams always told us to bring a towel. What do you recommend we take on our adventures?

Howard Tayler: A spare towel because the first one gets dirty really quickly, surprisingly quickly, frighteningly, frighteningly dirty.

Mary Robinette Kowal: So I always recommend good hydration. One of the things for the people who are in the live audience is that I have a notebook up here. I always carry a notebook with me so that I can jot down the thing that’s like, that’s super cool. And later, I don’t have to go through the process of like, oh, someone told me this super cool thing and I remember like three parts of it but not the fourth. I can actually just jot them down as people are talking.

Dan Wells: There’s another web cartoonist named Ryan North who does Dinosaur Comics. And he created and sells a T-shirt that includes on it all of the instructions in very small print to reinvent most of our modern technologies. And he sells it as the special T-shirt for time travelers.

Mary Robinette Kowal: That has just come out as a book.

Dan Wells: As a book, yes. It’s called How to Invent Everything. And the idea is that if you accidentally get thrown into the past, you will be able to re-create electricity and penicillin and all these other things. So that’s a pretty nice one to have.

Howard Tayler: So that book wrapped in a towel [laughter].

Kjell Lindgren: All right, so from personal experience, I would say a spoon. [laughter].

Dan Wells: Now we’ll tell you the real answer.

Kjell Lindgren: This is for low Earth orbit. I’m not saying planetary, you know. A spoon is important. Never pass up a meal. And then scissors. So we get issued a Leatherman, you know, a multitool that we have with us. We have all sorts of tools. And I would say that 99% of the time, just a pair of scissors was the handiest thing that I could’ve kept with me. I used that multiple times a day. I probably use the multitool maybe five times total during the entire expedition. But I cut a little hole at the top of the multitool holster and then tuck the scissors in there, put a lanyard on it. Oh, and you have to have a lanyard tying — you know, obviously connecting whatever it is that you’re using to your body. Because my radiation, personal radiation device, upon arriving to orbit, they were very clear about, you’ve got to keep this on you at all times.

You know, this is the only one you have, there’s no backups. So I of course stuck it in my pocket, thinking, I’ll figure out a way to attach this to myself at some point. And then spent a good two hours looking for it, terrified of having to make, you know, my first call down to mission control, hey, I already lost the personal radiation device [laughter]. Thankfully I found it in one of the multitude of pockets that we have on our khaki cargo pants. But I immediately then wire tied that to my — to the multitool holster as well. So I basically had that thing with me the whole time. But the scissors are super important.

Howard Tayler: Can I ask why — if you only get one, and everybody gets one, and everybody only gets one, and everybody who goes on to the spaceship gets one, why isn’t there one solution for keeping that one thing on your one person?

Kjell Lindgren: That is a great question. They’re relying on I guess our ingenuity to.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Well [laughter].

Howard Tayer: Make checks payable to.

Kjell Lindgren: Patented personal radiation device holster.

Howard Tayler: I call it string.

Kjell Lindgren: We use wire ties. We’re not going to stoop to string.

Mary Robinette Kowal: Yeah. And string is not an acronym.

Kjell Lindgren: Could be. I’ll work on that.

Dan Wells: He’s going to spend the next few minutes thinking about one. We have another question though.

Audience Member: Is there a particular NASA mission that has inspired your writings more than others? Or is it just NASA’s collective goal of exploring the unknown?

Dan Wells: For me, like we said, writers love to think about what goes wrong so that we can solve the problems. And so you all know now after that introduction that I’m going to talk about Apollo 13, which is a disaster and things went wildly wrong. But it is also such an incredible testament to ingenuity, to preparedness, to solving these incredible conflicts on the fly because you’ve already assembled the right people and you know what to do and you’re able to think outside the box. And I find it an incredibly moving and inspiring story.

Howard Tayler: I grew up on the West Coast of Florida. 16 years old, driving to school one morning, and there is a pillar of fire reaching into the heavens, terminating in a little tiny point. And I’m convinced, you know, I’m seeing, you know, the flame from the launch. And it’s explained to me, no, that’s not the flame, that’s just contrails and gas and it’s being lit by a Florida sunrise. So beautiful. So awe-inspiring to see from across the state us reaching up with this fiery finger and touching the heavens. That sense of wonder belongs in everything I do at some point. I can’t draw that picture in a way that will inspire readers the way that sight inspired me, but I can try to make up other stuff that comes close.

DongWon Song: Having spent all this time talking about the importance of people and narratives and feelings, I’m now going to talk about an inanimate object. And I will sometimes lay awake at night thinking about the Voyager space probe and this infinitesimally small thing in this infinitely large universe, just broadcasting its little message and going out there. And to me it’s just this really beautiful image and very powerful for reasons that I’m not sure I can articulate. But it’s just, it’s out there, and it’s going to keep going. And that is so amazing.

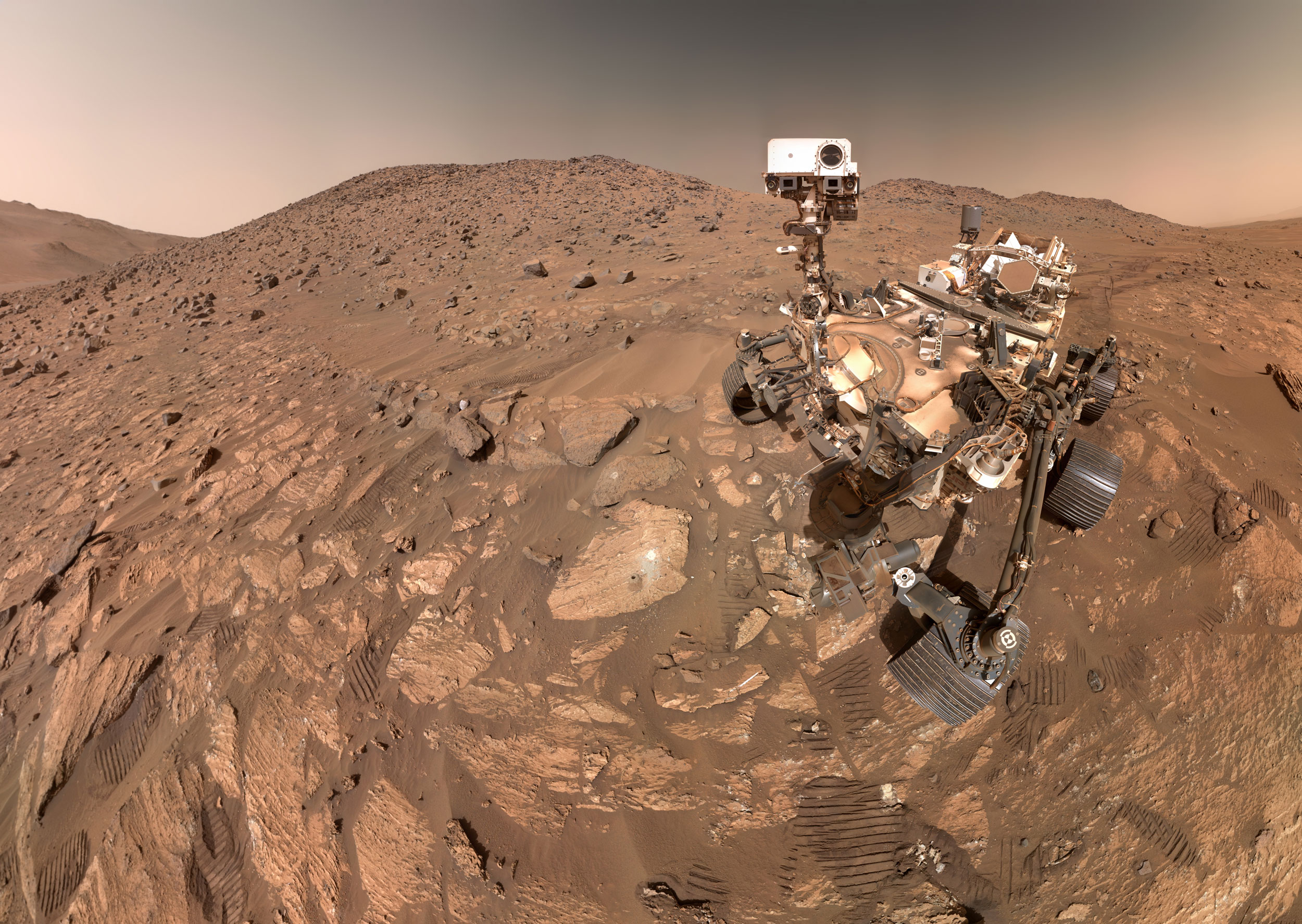

Mary Robinette Kowal: We’ve already touched on a couple of things that I was personally excited about. But the video of the Seven Minutes of Terror was so like such — I was watching that live. There were people — I live in Chicago. And there were people — there were bars showing that. Like you could go to a bar — and had I known that at the time, I totally would’ve been in a bar instead of my living room watching that. But I was watching it and like all of my friends were on Twitter and we were all sitting there rooting for that. And just it was like when we knew that it had worked, and everyone that I knew was cheering, it was like, yes, this is science! [laughter].

Host: We have another question in the audience.

Audience Member: I have a three-part question for the panelists. First of all, did you go to college? Or was there some other postsecondary training that you did? Secondly, what was the emphasis or major of that training? And then thirdly, what courses or instruction has been most helpful to you in your career as writers and editors?

Howard Tayler: I studied music, because the graduates of the chemical engineering program all came back to lecture to us and they were all dumpy, short, bald guys. And I thought that music would make me cooler. This is a true story. I went into software middle-management and at some point realized that at my heart I was a storyteller. And how hard can it really be to learn to draw comics? And the answer is, harder than I think. The one thing that I learned that — or the one piece of knowledge that I had at that point that made any of this possible is that I could learn to do it better. The thing — honestly, the postsecondary, post whatever training that’s been most valuable to me — and this is going to sound a little bit like sucking up — is being on the podcast with Dan and Mary and Brandon and DongWon and many of our other guests. Because I’m the cabbage head. It’s my job to learn everything and maybe sum it up in a pithy way. And I’m still learning as I listen to my friends.

Mary Robinette Kowal: I don’t have a degree. I was an art major with a minor in theater and speech. And for years I would mask that because I felt really inferior, especially when I’m sitting in a room where I know there are multiple PhDs and some of you have multiple, multiple PhDs. It’s not fair. But I left college to do an internship at the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia and went on to have a 25-plus year career as a puppeteer. So I’ve done everything from touring into elementary schools to Little Shop of Horrors, which is 125 pound puppet at a time in my life when I weighed 127 pounds, to Sesame Street. I’ve done film. I’ve done some television. And for me the thing that has been most useful in my life has been learning how to communicate to an audience. I’ve been able to take that into every other thing that I’ve done. And specifically there have been two pieces of advice from puppet theater that — well, one of them is actually my dad, but I’ve used it in puppet theater. Which is done right or done over. That you do it, and if it’s not right, you do it over. And that you can iterate to being what you want to be. The other thing is that, in my field, that you shoot for 100%. This is something that my mentor said, that you shoot for 100% every time, but that you learn to be happy when you’re hitting 80%, that you’ve actually had success. That just because there’s been one failure doesn’t wipe out all of the other failures that have happened. And those two things have allowed me to just keep going even when what I’m working on doesn’t succeed. I just try it again.

DongWon Song: So I have a double major in English and economics as my undergraduate degrees. And that sounds like the perfect setup to be a literary agent, which is what I am. And you know, that double major or econ came about just because when your parents are Asian American immigrants and you call them to say, I am quitting my engineering program, you need something so that they don’t actually disown you on the spot. And you know, I have found that the econ degree actually helped me more than the English degree in a lot of what I do, but not because it makes me good at business. Because economics isn’t really about how to do business. It has taught me how to think in systems. And when you think about systems and you work in science fiction and fantasy, world-building is really important. So it allows you to ask the question of, if we make this one change, what are going to be the knock-on effects for that, right? If we change this global variable, what happens to the people who live in this world? So I use my econ degree all the time to think semi-rigorously as far as fiction requires about what are the consequences of the rules in the world that we’re imagining in. How do we make sure we’re building an internally consistent story?

Dan Wells: I have — in undergraduate, I have one year of — I studied archaeology for one year and then English for two years, and that ended up being a bachelor of arts in English and editing, because the archaeology didn’t really count for anything. It was awesome though and I love it. The most important thing that I think, the part that I keep going back to as I’m listening to these other stories, is actually something that my fifth grade teacher taught me. Which was how to spell pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis. And I say that in all seriousness. I think it is arguably the most valuable thing I’ve ever learned. Because it taught me, first of all, how words work and how to read a new word and figure out how to say it and what it means. It taught me that I can do that, that I can explore something new, that I can learn something new, that I can figure something out on my own, and that I don’t have to be afraid of big words.

And I 100% guarantee you that there is a very direct through line from that fifth-grade teacher to me being an author today.

Howard Tayler: I had not heard the story about that long word that I can’t pronounce. I also hadn’t heard about the archaeology stuff. And it occurs to me that, you know, learning to dig up and learn about bodies helps you hide them. [laughter].

DongWon Song: It also explains the hat.

Dan Wells: Yes. For those not benefitting from the video feed, that’s a joke we make on our show. I don’t know if we make that on your show because maybe there is one or maybe now we’ll get in trouble for not having one. But I do, I have an Indiana Jones style adventuring fedora as part of my author uniform so that people recognize me. Yes, I studied archaeology for one year in college. And there you go.

Host: Well, as weird as it is, I think that’s a perfect place to end [laughter]. Hey, how about a big JSC round of applause for our panel today?

[ Applause ]

I expected nothing less than an amazing discussion from you guys, and that’s exactly what we got. I think it was a perfect way to celebrate 60 years of NASA and the inspiration that comes with it. So I very much appreciate you coming on the show today. Thanks to our audience. Kjell, thank you for making some room in your schedule for this. And with that, we’ll wrap up. Thank you.

[ Applause ]

[ Music ]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. That was a really fun conversation we had on stage for the 60th anniversary of NASA. I was really proud to bring them on and have a discussion about science fiction. Because really that inspired a lot of folks here on the site. And you can even tell in the audience, people were really excited that we got to chat with those folks. So if you want to learn more about the 60th anniversary of NASA, we have a website, NASA.gov/60. You see what happened across all the other centers all over the United States here for the 60th anniversary of NASA. We have other podcasts you can listen to across the agency as well. We have Gravity Assist over at headquarters about Planetary Science, NASA and Silicon Valley, and of course, Rocket Ranch.

You go to NASA.gov/ISS to find out what’s happening on board the International Space Station all the time. On social media, you can visit our NASA accounts, NASA Johnson Space Center accounts. In either case use, the #askNASA on your favorite platform — Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, whatever. Submit an idea for the show. Make sure to mention it’s for “Houston We Have a Podcast.” This episode was recorded on the 60th anniversary of NASA on October 1, 2018. Thanks to Alex Perryman, John Stoll, Pat Ryan, Bill Stafford, Norah Moran, Jeannie Aquino, Linda Matthew Schmidt, Brandi Dean, Megan — honestly, I’m sorry, I’m going to leave off a lot of people here, I don’t think I can get through everyone. But truly thanks to everyone who participated to actually make this happen. It was a big deal. Greg Wiseman, Eric Gambrell, just so many people. Also thanks to Mary Robinette Kowal, Dan Wells, Howard Taylor, and DongWon Song for taking time out of their schedule and come on to share their insights with the NASA community and with the listeners of ” Houston We Have a Podcast” for the 60th anniversary of NASA.

Very proud to spend it with you guys. And of course, thanks to Kjell Lindgren for taking the time as well. He actually adjusted his schedule to be with us today. So I really appreciate his time and his out of this world perspective. Happy 60th anniversary to NASA. We’ll be back next week.