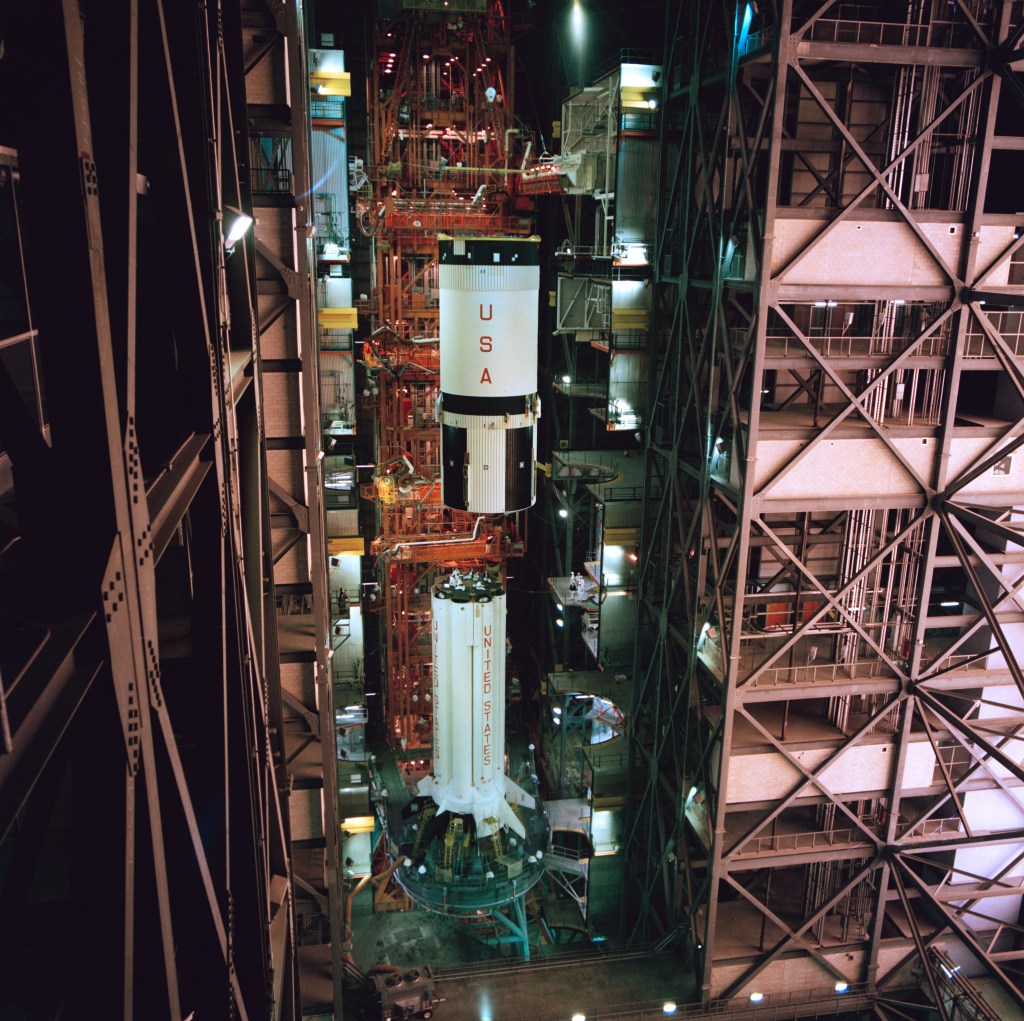

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

For episode 58, Dr. Tom Williams discusses isolation and confinement. His focus is on habitability and behavioral health and performance risks to space flight, and he leads a research team that looks into isolation. This is part two of a five-part series on the hazards of human spaceflight. This podcast was recorded on June 22, 2018.

Exploration to the Moon and Mars will expose astronauts to five known hazards of spaceflight, including isolation. To learn more, and find out what NASA’s Human Research Program is doing to protect humans in space, check out the “Hazards of Human Spaceflight” website.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host):Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 58, Isolation. This is Part Two of our five-part series on the hazards of human space flight. I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast we bring in the experts, NASA Scientists, Engineers, and Astronauts, all to let you know the coolest information about what’s going on right here at NASA. So today we consider another hazard of human space flight, isolation and confinement. We’re talking with Tom Williams, Element Scientist for the Human Factors and Behavioral Performance in the Human Research Program. He focuses on areas like habitability and behavioral health and performance risks to space flight in addition to many other areas. He leads a research team that looks into the hazards of human space flight including isolation. So with no further delay, let’s go lightspeed and jump right ahead to our talk with Dr. Tom Williams. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host:Okay, Tom. Thank you for coming here today to talk about the second of our five hazards. This one’s on isolation. I appreciate your coming on.

Dr. Tom Williams:Very glad to be here. Thank you.

Host:So this one, this one’s interesting. And this one is a lot of — when I think of isolation I think of a lot of songs, you know, like David Bowie. You think of Space Oddity, right? Out there alone in the universe. What am I doing? But this is an interesting — it’s an interesting concept because I don’t know if there’s any place on Earth where you can be potentially as far away from Earth as you are with exploration and space travel. It’s a huge consideration. So just sort of going through the isolation. What is isolation and what have — what do we know so far about what isolation does to the human body? What do we know?

Dr. Tom Williams:Yeah. So when we think of isolation, it’s probably important to think about what in essence it does to us as human beings because we’re very adaptive organisms. I mean we’re very resistant and adaptable to different changes in our environment. And what isolation does is sort of remove that context of adaption because, when we’re isolated, we’re not being able to engage our environment in as many different ways as we are when we’re not isolated. And so, therefore, some of the things that we depend on to help us adapt to the different challenges that we may encounter are now removed from that. So it sort of creates that barrier to allow us to kind of be that adaptive resilient human being that we know we can be. So it’s good to think of isolation as sort of three different areas. There’s a social disconnection because when you’re isolated you’re not around other people. It also challenges our ability to self-regulate because we typically learn to respond to our environment by the manner in which other people may react to us.

And so there’s an important component to that. And then long-term, our mental representations of how we interact with our environment are often determined by how well we feel we’re being successful in interacting with our environment. So in an isolated environment, you’re in a monotonous area, in an area, an environment that doesn’t give us kind of that challenge and that feedback on how things are different each day and how we get to adapt to those differences.

Host:Yeah. So there’s no room for correction because nothing is correcting you. So you’re [inaudible], you can sort of spiral into any direction, really, without any sort of guidance.

Dr. Tom Williams:Yeah, it’s a great point because oftentimes we like to think about the fact that, well, we wish we had less demand in our environment, but then when you get less demand in your environment it’s not as interesting and we don’t get to basically see how far we can go with some of the demands and challenges that we have in life. And if you think about what we ask a crew — we tend to look for really high-achieving, high-performing individuals who are used to taking on significant challenge, and then you put him in an isolated and confined environment where there’s fewer demands placed on them. They may be more extreme, but fewer demands over time in a long-duration mission, for example.

Host:So it kind of sounds like these fewer demands are almost kind of leading you — if I’m in an isolated environment, it almost would want me to — it’s almost like I’m bored, right? And so there’s not as much demand on me, not as much feedback, so because I’m not getting that response, I create a more maybe exciting environment. Maybe that’s why the behavior — is that a reason for it? Has there been studies on that?

Dr. Tom Williams:Well, you know, when you look at some of those social deprivation, kind of the sensory deprivation experiments that were done in the ’60s where they put individuals in a completely isolated chamber, removing all sensory stimulation. So they’re in a tank of water, no light, no sound, and people can’t last in that environment very long. And they started to have vivid imaginations, vivid like almost hallucinations. The mind wants to be engaged. The mind wants to be experiencing different stimuli, so it is important to keep that constant interplay between what’s inside us and what’s going on outside us, and to get feedback on how effective we’re being. And so I think that’s part of that consideration for how do we make sure that we keep crew focused, engaged in meaningful and relevant activities so that they feel as though they’re being successful on a long-duration mission where there may be fewer things to do.

Host:So is that some of the results that come from these studies in the ’60s? You realize that there needs to be some sort of stimulus, so you give them activities to do, but they have to be maybe a kind of specific activity to make sure that they are stimulated.

Dr. Tom Williams:Yeah. One of the things we saw — Shannon Lucid, when she was on Mir Station, one of the things she emphasized was the need to stay engaged in something that you enjoy doing because you would have periods of time. So one of the things she did that was really fascinating is she took 100 books with her to read to her children. So she recorded these books. Now the problem, of course, on a long-duration mission, we may not be able to have the — can’t afford the weight that would be required to take large numbers of books.

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:We’d have to do it electronically or something of that nature. But that shows you where she was proactively thinking ahead about if you’re going to have periods of time where you’re not going to have something to do, really high-achieving, engaged people will find something. And so being planful about those type of demands helps you be prepared for it.

Host:See, in that instance, you have to be engaged, but not just with yourself. It sounds like she was connecting to the ground. She was down-looking to the ground to connect with another person. So she’s planning ahead, not just to stimulate herself, but to connect, to be with other people, and to have that sort of communication.

Dr. Tom Williams:Exactly. Exactly. And that’s an important observation because that’s what we need to characterize and understand. And we know on station today, crew can, when they have time, and they’re kept very busy on the station obviously every day with Sundays they attempted to give them off-time.

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:But they can do a connection straight down to their family on a voice-over-internet telephone, satellite phone, and so they can facetime as well. So that’s an important connection. What we have to think about is how will that differ? What impact will that have when there’s a time delay —

Host:Oh, yeah.

Dr. Tom Williams:— and you can’t have that instantaneous feedback, that social connection that we know is important for human being.

Host:Yeah. Definitely, once you go farther away from Earth, it’s going to be harder to communicate. So I want to jump away for just a few minutes to share this clip from my talk with Dr. Mike Barratt, a space traveler himself, and a medical doctor who has had experience with communicating with Earth from space, but reflected on continuing communication out into deep space.

Host: Well, we’ll start with this. We’ll start with — is there a certain level of communication that’s needed to maintain the crew’s health and feeling like they’re still connected and not so far away from Earth?

Mike Barratt: I think that as we move towards exploration of deep space we have to actually look backward, not forward, for the answers to some of these problems. Now, if you were to look at what I consider one of the greatest voyages of discovery of all time, Captain Cook’s circumnavigation aboard Endeavor, where they were lucky to find a merchant ship or a whale ship that might be going to their home port maybe years into their voyage. The crew would draft some letters, hand that to them, and hope that the ship would make it there safely sometime in the next year. And that’s — that letter-writing campaign was kind of how things were done. If you were to tell them, hey, look, we got a system where, given a few minutes to several hours, you can get a message back to Greenwich and then they can communicate with you before the day is out, they wouldn’t have believed you. So, basically, what we have is a revolutionary capability compared to the means that supported exploration missions for centuries.

And so, can we do it? If course. We have. We can do that. Now we have to crew and we have to design accordingly, and really move towards more mission autonomy. And we’ve spoiled ourselves in a way by having such broad bandwidth and real-time communication for the station. But the station is a laboratory, and it is designed to produce as much science as possible, and that really depends on real-time communication. Whereas heading to Mars and some of the other deep space destinations, we’re not in that paradigm. We are really all about exploring and what we need to do in maintaining the ship and maintaining the crew and supporting the mission. Most of the responsibility has to really be given to the crew.

Host:And that’s a big one, right? The Space Station — there’s — it’s pretty close to no delay whenever you’re talking, and that’s why you can have back-and-forth real-time communication with the ground. But as you go further out into space, now that signal is taking extra time to travel back and from Earth and Mars. Depending on where the Mars and Earth are positioned in the solar system, it can be up to a 40-minute roundtrip, right? Twenty minutes out, 20 minutes back.

Dr. Tom Williams:Right.

Host:So are we planning for that? Are we making sure that communication, even if it is delayed, is a regular part of living on another planet?

Dr. Tom Williams:We are. And part of what we’re looking at is more autonomous systems that allow for the individual to be able to carry out the activities without the constant interplay between Mission Control and ground on getting feedback. So some of the things that starts to help us anticipate is if there are training requirements that – do we need to train crew differently if there’s no Mission Control that they can reach back to to make the procedure they’re about to engage in is the right sequence of procedures. So part of our research program looks at how do we make sure that procedures are sequenced in the right way to ensure that they’re efficient and effective so that we don’t add stress in that way. Another thing that we’re looking at is, how do we determine if your schedule needs to be changed? So now the crew schedule with slight modifications by them is basically handled by ground, so Mission Control will determine what the schedule will be for the day.

On an autonomous mission, more autonomous, where there’s less interplay, how will the crew determine if they want to change their schedule and what might that schedule change — what’s the impact of that over time? So maybe they don’t want to do something at that particular time that it was scheduled, and they put that off. Well, what’s the impact of putting that off and how does it then alter other sequence activities that would need to follow?

Host:Yeah.

Dr. Tom Williams:And those are important things we want to look at.

Host:Because if they get — if they put it off, they’re not going to get feedback that says hey, don’t put that off for, you know, it depends, up to 20 minutes. Somebody recognizes that they’re getting — or maybe 20/40 minutes — recognizes that they’re putting it off. Hey, you weren’t supposed to do that. But by the time they get the feedback it’s already gone.

Dr. Tom Williams:Right.

Host:So that’s where that level of autonomy comes from. So — and that’s part of regular life on station, too, right, is having that feedback. Is — I know the astronauts are so busy just day to day. I mean, they have scientific experiments that they’re running constantly throughout the day. They got to maintain the Space Station, too. So if something breaks, they got to fix it. And then on top of that, they have to work out. Is a lot of these tasks — I mean, is there anything in addition to that to make sure that they are receiving this sort of stimulus and making sure that they don’t feel isolated? Where does isolation come into their day to day?

Dr. Tom Williams:I’d say the isolation is more — because there’s great social cohesiveness that exists on station among the crew.

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:So with the number that they tend to have there, there is that sense of connection with the crew. And that strengthens over time. But what’s interesting is you’ll — you sometimes will note that crew, as the mission goes on, will tend to spend more time taking pictures and looking at Earth through the cupola. So do we infer from that that they’re missing that social connection on Earth, because one of the things we see when crew come back is sort of an increase and a sense of universalism, so they have an expanded view of the world, and part of that is probably because they’ve been able to see it from a distance as opposed to just on Earth as we all see it. And the other thing that we can conjecture on that is that if they’re looking more at Earth, is it because they’re getting closer to their mission ending? Or is it because they miss the people on Earth more as time goes on? And so part of that psychological connection is part of what we need to understand as we look at some of our high fidelity analogs to make a determination what are the processes that are causing the changes in behavior. And we had one, for example, one study that we looked at, the results of — from — that was run in Russia, the Mars 520. And one of the things that was noted in the six crew members in that analog was that there seemed to be an increase in what we might call psychological [inaudible], so their energy levels were less as time went on. So near the end of the mission they were less active, and was that less activeness as a result of being disconnected from the outside world more, was it a function of having less stimulation from their environment? And those are things that when we see these results then we need to ensure that we characterize them appropriately to see was this a function of the individuals within that analog, or does it generalize out to potentially our crew, and then we need to better understand that.

Host:I know, I know. Why are you cutting away from the conversation, Gary? This is the last one, I promise. But who better to comment on do you feel isolated than an astronaut himself. Here’s Mike Barratt once again.

Host: Did you ever feel isolated on a Space Station or maybe because it’s so close that maybe you felt pretty connected?

Mike Barratt: I think that the only times I ever felt isolated up there was when I knew there were events going on on the ground that I really wanted to be a part of. Mostly family events. Other than that, not really, for two reasons. You know, number one, all those habitability factors that I mentioned.

Host:Yeah.

Mike Barratt: But number two, where you are is just so magical. I mean, it captivates you. You are mostly feeling how amazing it is to be where you are and feel what you’re feeling and see what you’re seeing than you are wishing that you were elsewhere.

Host:So I’m guessing there’s a lot of studies, really, or maybe a few, at least, that are looking at behavioral changes on long-duration missions because that’s what we’re doing now. Crews that are going to the Space Station are up there for up to six months. So are you already looking at behavioral changes, especially in performance and how well and how efficiently they’re doing their tasks, from beginning to the end of the mission?

Dr. Tom Williams:We are indeed. We have a number of different analogs that we look at. In fact, we just had the human exploration research analog, the HERA Mission that just ended this past Monday night.

Host:Oh, that’s right.

Dr. Tom Williams:And we’ve had crew in there for 45 days, and what we look at, across that 45 days — of course we do a baseline — but then across the 45 days we’re looking at potential changes in cognitive processing. So we have them engage in a number of tasks that are space-flight-relevant. But we’re also assessing using a cognition battery that was developed specifically for astronauts because of the different impacts that we think space may have, space flight may have on the cognitive processing. So we’re looking at that across time. We’re looking at their team interactions across time, how that may change their cohesiveness, their sense of cooperation and collaboration with one another, and we’re looking at how they eat, how they sleep, and with the crew that we just finished with, we also had them on a sleep-restricted schedule to determine what was the impact of that, and there are a number of different factors that we look at and then we consolidate that information, recognizing we brought four people in to do a task.

What is the impact when we give them structured tasks to do and then how does that change the way they relate to one another, the way that their mind and body starts to adapt to this demand? And then we’ll use that to generalize to what do we need to prepare for countermeasures for any of those factors that we think are impacting them.

Host:HERA is very interesting because it’s just this habitat really that simulates like this is probably sort of what a Mars habitat, a lunar habitat, whatever, and other planetary habitat would look like. And it’s just living and working in this habitat. But the reason you’re doing it is exactly what you’re saying, it’s to study these behavioral changes. You do these tasks and see how they react to that. Obviously, you know, astronauts are going to be there and they’re going to be working hard just like they do on the Space Station. But whenever — there’s going to be times, there’s going to be times where they’re going to have so much work that they’re going to be sleep-deprived. So exactly what happens to that? Is there comparisons we can draw? Do you see a lot of the same things happening with the workload and the behavioral changes on the station and in HERA? Is there a lot of crossover there?

Dr. Tom Williams:You know we’ve had some great researchers, Chuck Czeisler and Laura Barger and then Erin Flynn-Evans of our own NASA Ames Research Center that have looked at using actigraphy which is an indirect measure of sleep. So when we sleep we tend to not be moving around, hopefully. And so the actigraphy device measures how much activity the individual is engaged in, and then from that we infer the person is sleeping or not. And in one study that they looked at in 21 crew, they found that about 29% of the time crew aren’t sleeping well. Their circadian rhythm has been dysregulated.

Host:Wow.

Dr. Tom Williams:And that can be due to a slam shift, for example. There was a docking with a resupply vehicle or a Soyuz craft that comes in in the middle of the night where they normally would have been sleeping which then, because of the schedule, they’re don’t really get to catch up on their sleep. They can’t sleep in the next day because of activities or requirements. And so — and the research tells us that it takes about 13 hours of sleep to sort of recover after your circadian has been dysregulated, so you’ll need to get extra sleep. But we tend to see that, although it’s very individual, crew will tend to average about six hours of sleep at night on station. Now we know that’s not what they need because when we measure the sleep before they go up and when they come back, they’re averaging about seven hours of sleep. So it could be a function of high workload. It could be a function of just circadian dysregulation because of the 16 sunrises and sunsets that they observe each day.

And for here on Earth, our sleep cycle and our circadian is regulated by the sun rising and setting for us. That’s what signals us to be on that cycle. So it’s understandable if they’re getting that exposure that they’re now — that’s part of that challenge to the adaptation that we started talking about. The body is incredibly adaptive as we learn if we fly to a new time zone. In about two to three days we can adapt to that new time zone. But 16 new time zones a day makes it more challenging [inaudible] adaptive.

Host:That’s right. You can almost call the Station the time zone of its own. You know, there’s very — there’s no places, there’s no few places, there’s no places on Earth where the sun rises 16 times in a single day —

Dr. Tom Williams:Right.

Host:— in a 24-hour cycle. But that’s interesting. You know, I’m glad you guys aren’t studying me because I would be all over the place, and I like my blackout curtains, so, you know, the sun rising and sunsets does not have any impact on me. But are you guys questioning the crew? Are you — you know, when you’re trying to understand why they’re getting less sleep, do you — do they give you feedback? It’s because maybe at the end of the day I’m so exhausted from a day, I just want to look out the window for a little bit, and I’m kind of going into my sleep time, and to just, to look at the window, and just sort of relax for a bit. Are they doing stuff like that?

Dr. Tom Williams:Yes. So the crew have been debriefed, and among the reasons that they cite and in particular a good reason to have private sleeping quarters on station or on a craft, one of the reason is they may get disturbed by another crew member who gets up to go to the bathroom at night, much like married couples might experience if someone’s making noise. That noise is now causing the person to stir. Other activities might be noise or an alarm that goes off that needs to be attended to. And the sleep cycle itself may be interfered with by just the intense workload. So we know that stress and the demands that are placed upon us during the day will cause the sleep architecture to shift and then make us more vulnerable to being awakened, and some of that goes back to the evolutionary time where in our evolutionary past those humans that were more alert to potential danger in the middle of the night were the ones who passed their genes on later.

Those who slept deeply through the fact that a saber-toothed tiger may be coming in the cave that they were sleeping in, they tended not to survive.

Host:Yeah. Natural selection and — yeah. It — you’re not going to survive a saber-toothed tiger for sure. Now we’re talking about some studies to recognize these behaviors, to understand what is happening and why it’s happening. Are we also looking into these countermeasures to see — we understand a little bit of what’s happening and we’ve come up with these methods on how to maximize crew performance.

Dr. Tom Williams:Yeah. We’ve looked at a number of different countermeasures, some of which are sleeping medications. So, for example —

Host:Oh.

Dr. Tom Williams:— looking at what is the best dosage level of a sleep aid that allows you to wake up in the middle of the night and respond to an emergency situation. So that was one great research project that was done that basically allowed us to then determine if someone is awakened by an alarm, how responsive can they be on which dosage level so that we ensure that we’ve got the right dose and the right medication so that, although we want you to sleep, we don’t want you to sleep through an alarm that may have needed your action to save the process that was now being threatened that the alarm was alerting you to. So that’s one approach as a countermeasure. The other is to teach some of the good classic [inaudible] behavioral skills that allow you to self-regulate, that allow you to be able to go through a series of relaxation processes, being mindful about what are the things that are stressing you and then self-regulate those in such a way that the stress levels don’t raise as high as they would have without that, that then helps modulate some of that reaction to stress that would rob us of our sleep.

So a number — and then other factors are to basically look at what within your private crew quarter area, for example the lighting system, just like on our iPhones, we can adjust the settings to ensure that we’re not getting that bright blue light at night that would stimulate our awakening, we’ve changed the lighting around the private crew quarters on station. And we have a lighting effects study going on now that’s looking at as these lights are adjusted, does that have an impact on the sleep cycle of the crew members?

Host:You know, after learning about that, that lighting effects study, I purposely downloaded a blue light filter, so that way, if I’m looking at my phone at night, it get’s that warm screen because I recognized that that is something that really can affect your sleep and, therefore, your performance. And that’s actually a good bouncing off point is we’re talking a lot about sleep and how it affects performance and behavior which is a huge part of isolation, too. It seems like getting more sleep can maybe help with some of those feelings of isolation and behavior changes. Is there a correlation there?

Dr. Tom Williams:Well, there’s probably a happy balance that you get because sometimes when people are isolated they sleep more —

Host:Hmph.

Dr. Tom Williams:— but they sleep more because they’re becoming more depressed or they’re becoming —

Host:Oh.

Dr. Tom Williams:— because of that lack of engagement in their environment, there’s fewer stimuli, they’re becoming more bored, it’s more monotonous, and people who are bored in a monotonous situation tend to doze off and tend to — because of the lack of stimulation. So there is unhappy balance that we have to find. And we know that sleeping too much can be as bad as not sleeping enough. So finding — and the interesting thing is there are great individual differences that people have in terms of how much sleep they really need. We pretty much know that almost every human being needs at least four hours of sleep at night just to maintain their ability to do things.

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:But when you’re not getting that sort of optimal level, you’re going to notice differences where they might have little periods of microsleep or doze off for just a moment. They might not even be aware of it. But the optimal is seven for most people.

Host:Hmm. Four hours is just to survive. Beyond that, that’s where, you know, that’s where the behavioral performance and making sure long-term health is maintained. That seven is good. You know, we’re talking a lot about station and we’re talking a lot about space flight and sleep. I kind of want to take a step back and think about, you know, beyond space flight — space flight is a great example of isolation because you’re literally in a capsule far away from everything. But it’s not the only place where isolation can be studied. Are we polling some studies and data from other instances of isolation? Like where else could humans be isolated that we’re getting this information?

Dr. Tom Williams:Well we certainly use our analogs a great deal. We also look across at, for example, submarines, and we know that individuals will be out on a submarine for anywhere from six to nine months on occasion. So what we get from that is what it’s like to be isolated, but it’s not a perfect analog for us because most of the crew on a submarine are much younger than our average age astronaut of about 42. The crew on a submarine are going to be primarily much younger in that mid-20 range for most, and then you’ll have a small contingent of maybe mid-30s. And they have more variety, more recreation, more opportunities to interact because there’s a larger number on a submarine than the small crew of four or six —

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:— we might have. And then when we look at, on an oil rig, for example, same thing. We’ve got — there are certain similarities — they’re isolated, they’re sort of away from most of the social connection that might be there, and you tend to get high-achieving individuals who have — they’re working in an extreme environment, so they have to be vigilant and attentive, and there’s stress and there’s new technology that gets introduced, and so they have to be adaptable to those demands. But, again, they — and they will get some sleep cycle adjustments because of the shifts that they have to pull. But what we find is that they’re not the perfect match. And so we take pieces of each of these analogs and these different groups and we put together into this sort of a mosaic that says we’ve got some understanding of what human beings are like in this environment, and we can generalize to this level.

And we get some in our high-fidelity analogs, and we get a little bigger understanding. But the best analog is the Space Station itself because there we’ve got the full complement of adaptations that have to be considered and that is the altered gravity, the other for-space flight hazards that you’re series is focused on.

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:All of those come together into the human. We have to understand the full complement of how those may be impinging on each of those areas. So is isolation in confinement much worse when you’re in an altered gravity environment —

Host:Oh, yeah.

Dr. Tom Williams:— at great distance from Earth? And that’s part of what we’re looking at. And some of our research is we’re looking at when you have a stress condition in altered gravity that gets irradiated, is that worse than just being isolated, just being stressed, or just being irradiated? So we’ve tended to focus more on the individual risk. But we know our crew are going to experience in an integrated potentially synergistic way. So how do we anticipate that?

Host:That’s very interesting. Yeah, it does make sense to just focus on one thing because that’s not what the environment is. The environment’s going to throw at you altered gravity and radiation and all and being far away. All these different hazards have to come together, and you have to make sure performance is maximized. And you’re not just, all right, we fixed the isolation thing. Oh, yeah, what about radiation? What about, you know, change in gravity, all those kinds of things? So what element — let’s pick on oil rigs for a second. What elements or oil rigs and the folks that work there are we looking at and taking to space flight and how we deal with isolation?

Dr. Tom Williams:Some of what we look at there is some of the occupational surveillance that gets done with oil rig workers. So how does their sleep get interfered with by the demands of their schedule when they have sleep-shifting? So just like we have on a slam shift on station when a Soyuz docking comes in. If they have some event that occurs that alters their sleep, what’s the sleep cycle changes that we see? We also look at — they tend to be sort of high-performing extreme environment individuals. How do they handle the stress? How do they — and they’re gone for periods of time and then reintegrate with the family. So there’s a multiple kind of context of different things that we can look at with them that help inform us about if they’ve got an effective countermeasure. Then we look at how might we adapt that to our circumstance.

Host:Yeah, that’s big. I mean just — you’re not just going to let someone just go on an oil rig and say all right, ‘bye, have fun. It’s the monitoring aspect that really helps you to understand what’s going on throughout the whole time they’re on an oil rig, and that — and you translate that directly to a space flight. That’s why we’re doing it. That’s why we’re actually paying attention and monitoring these changes over time. And that’s a huge element that I think is important for astronauts, too, you know. Astronauts — I always look up to them because they’re such amazing human beings, just physically, mentally, just unbelievable what they can endure. And that’s different from just me going out on an oil rig or up there because they are just superior human beings. And I think that’s having that as an element, as a factor for understanding isolation is pretty big. You have to have high-performing individuals. Sure, you as a researcher can control some things, but ultimately you’ve got to have the best of the best that are going out there.

Dr. Tom Williams:Agreed. Which has been — and we do make great efforts to make sure that individuals who apply fully understand what it is they’re asking to be a part of —

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:— and then they go through a very demanding process to make sure that they reflect those characteristics that are going to position them for success, to be honest. I mean, we want to select people who are going to be successful operating in the extreme environments that we’re going to place them in. And so there’s great demands that will placed on him, great achievements that are possible. How do we align the capabilities and aptitudes with those demands? And that’s part of what our selection process looks at.

Host:Mm-hmm. You know, I just realized we’ve been talking a lot about we, we here at NASA, and we’re talking about a big broad thing. But you have a very extensive yourself. So how did you officially come to NASA and what’s your background in that led you to start studying isolation?

Dr. Tom Williams:So I have a PhD in Clinical Psychology from St. Louis University, and that was probably, in part, the foundation that helped me find myself here because of the great connection between the science and practice that the program offered there. And part of what my background was was in running an executive health program for executive leaders and developing leader development strategies and approaches and 360 feedback tools for them. And in 2009 I was asked to come and help with astronaut selection and found that really an exciting opportunity and decided if I ever had the opportunity I wanted to come and be a part of NASA’s mission because of the importance of it, the strategic nature of it, and because of the contribution that it makes to our nation and to the world to be honest. So I found the opportunity in a position that became available that someone here at NASA made me aware of that they felt I would be an appropriate person for that.

And I have not been disappointed in the opportunity.

Host:That’s awesome. You know, I didn’t realize you were part of the selection process. You know, thinking about it from your psychology background, and when you were looking at these individuals and maybe interviewing them, what about their personality qualities about them did you really look for to know that they were going to be able to handle the stresses of space flight and be able to handle isolation instance?

Dr. Tom Williams:Well, just like you might imagine. You’re looking for individuals who have demonstrated that they’ve been able to handle challenging experiences, challenging demanding occupational backgrounds, and shown an adaptability to these differing demands that we know we’re going to place on them. So it’s the adaptability, it’s the achievement orientation, it’s the resiliency. You don’t have to be the perfect individual, but you have to be the individual that has demonstrated that you’re able to learn from, adapt, and grow stronger as a result of the experiences that you’ve encountered and the demands or the different challenges that you’ve overcome. So just like explorers of old, the people who planfully look at what has to happen, take steps to prepare themselves to do those adaptations, those demands, to meet those demands, are those individuals who are going to be successful.

And that’s what we’re looking for is — you now, it’s — there’s an old strategist, Colin Grey, who once said, “We’re always going to be surprised by different events. We just can’t afford to be catastrophically surprised.” And so what we want are individuals who allow us to avoid being catastrophically surprised. So we want the right people with the right mix of skills, with the right abilities, who can handle those surprises that are going to come up that we can’t anticipate and plan for every possible outcome. But with the right, resourceful, adaptive individual, they can handle those situations and make sure that we achieve success.

Host:And you know because based on their resume, they have already handled that situation. I know just in our 2017 class I believe either two or three, I believe, of the astronauts that were selected had Antarctic expeditions. I just just in that small group. So you know they’re going to be able to handle a dangerous environment, a stressful environment. And then that translates perfectly to long-duration space exploration. And the further we go out, you know, they know they’ll be able to handle themselves. That experience goes miles. So also thinking about the stuff that you’ve done, especially here at NASA, are there any studies here at NASA that you’ve done specifically that you’ve focused on or are related to isolation or psychology?

Dr. Tom Williams:Well, as the element scientist, I look across the portfolio of the different risks that we have basically responsibility for .

Host:Okay.

Dr. Tom Williams:So we’re looking at nine of the 32 risks that are focused on reducing that risk that we need to have reduced in order to basically successfully go on a long-duration mission. So my position identifies are are the research kind of lanes that need to be addressed, and working closely with the discipline scientist for each of those risks, then integrating and determining how best to meet those, either with a directed study, usually with a — the default is always to go with a solicited study. And we bring in some of the most premier researchers in the world and a lot that are focused on — their expertise is really designed to help us characterize the risk, reduce the risk, or develop countermeasures once we’ve understood the risk. And so we’re very fortunate to have great researchers like — you heard me mention Chuck Czeisler and Laura Barger on the sleep area.

David Dinges from the University of Pennsylvania and Matthias Bazner working with us closely to help identify what are the impacts of sleep and what are the cognitive changes that may accrue as a result of that. So putting those studies, building a solicitation that helps us look out to say what are the ways in which these risk factors may interplay and how do we then design research to help us characterize the risk to ensure that we’ve got the appropriate understanding to prepare our crew appropriately or to develop countermeasures in case that risk gets realize in some way?

Host:So you’re like a — you’re a big-picture guy. You’re looking at the whole landscape and then picking these studies. So you’re talking about nine of the 32 risks you said. You said 32. The 32 risks of what? Of the human in space?

Dr. Tom Williams:Right. So we have the five space flight hazards.

Host:Right.

Dr. Tom Williams:And then there are 32 risks that the Human Research Program has identified that we look at and know that there is some evidence that it may pose a risk to either crew health or performance, or to the mission. And so our risks are then — our job is to identify, well, what’s the evidence that we have, and what’s the gap, the research gap, the lack of understanding that we may have about that particular risk, and then how do we bring to bear an understanding that characterizes that risk, gives us a tool or technology that may help us counter it, and gives us a method to basically provide to the crew to help them reduce that risk. So, for example, we talked about sleep as one of those risks.

Host:Mm-hmm.

Dr. Tom Williams:And then build — basically take our capability to the extent that we’ve reduced the likelihood and consequence of that particular risk being realized on a mission. And so that’s our goal, is to bring scientific information to bear, and we’re in an applied science program, so bring scientific evidence to bear that helps us then reduce that risk to an acceptable level. Because of the extreme nature of space flight and just the hazards that are always going to be there, we can’t run a mission without any risk.

Host:Okay.

Dr. Tom Williams:But how do we get it to an acceptable level so that we were able to successfully send and return a crew safely back to Earth?

Host:Mm-hmm. Acceptable is a pretty subject sort of feeling, too, because what is acceptable? What is — what do you determine that you are comfortable with that amount of risk? It sounds like maybe it has to do with knowledge. You know, you’ve looked at the risk and you’ve asked a lot of questions, and answer a few of them, and understand the overall capabilities of the risk. And maybe it’s that understanding that allows you to determine that, yes, maybe this is an acceptable level that we’ve reached. Is that kind of the process?

Dr. Tom Williams:It’s a good description of it. Basically what makes it acceptable is we’re not going to lose crew, we’re not going to harm them in some way, and we’re going to have a successful mission. So we want to get the percentage of risk down to a level that the leadership makes the determination this is now an acceptable level where we’re not going to lose crew nor harm them in some way nor impact the likelihood of achieving the mission’s success. So that’s what determines the acceptability.

Host:Okay. So you talked about you’re focusing on nine. Sounds like sleep, just sleep is a category of its own, right? Is sleep just a risk? And then you have several studies that are looking just at that risk? Is that how that works?

Dr. Tom Williams:Exactly.

Host:Okay.

Dr. Tom Williams:So with our sleep risk area, we have about eight different gaps that we have — we know that we need to address. Now sleep is one of those areas that we have probably characterized most of the risk to an acceptable level.

Host:Oh.

Dr. Tom Williams:So we know that — we know how much sleep people need. We know we don’t get enough, and we know that we need strategies and countermeasures to address it when we don’t get enough. But some of the others are the behavioral risk factors. So our behavioral medicine risk deals with when we’re isolated and confined, what are the psychological processes that start to accrue that may potentially create a vulnerability to become depressed or anxious or to feel the lack of energy to get the job done that the crew needs to do? And there have been little hints of that, that a crew both in analogs and sometimes on mission, you’ll see evidence that something is causing a decrease in activity. So the question is, does — is that moving toward a condition that would concern us or is it just an adaptation that the person is making?

And we don’t — that’s — again, we don’t want to be surprised in a long-duration mission by something happening. So we want to look at that carefully, address the evidence that we have, and then develop a countermeasure in anticipation that that may happen. So, therefore, deal with it ahead of it.

Host:Hmph. Do you notice — you know, thinking about this idea of maybe isolation, depression, and signs of it, maybe decreased performance and abilities to complete tasks. You talked in the beginning of our discussion about looking out the window and how often they’re doing that. Are you monitoring how often they’re doing it or for how long they’re doing it? Is that part of the study, to determine, oh, maybe this person might be feeling a little off today because they’ve been at the window for way longer than usual.

Dr. Tom Williams:We don’t do that precisely. We just note activity levels. But one of the things we will monitor, for example, are journaling. So —

Host:Ah.

Dr. Tom Williams:— in the crew journal, and they do it anonymously, but we’ll make note of how many references they may make to home or to family or to relationships, and to sleep. So what — when they’re journaling and writing about their day, what are the types of things that draw their attention? There’s a famous study, sort of referred to as Aging With Grace where they took the letters that young women would write to enter a novitiate to become a nun. And they could predict, based on the letter that was written in the early, late teens, early 20s, they could predict who was likely to have Alzheimer’s with a high degree of predictability later in life by the nature of how open, how expressive, how many details they talked about in their life, how many things they had engaged in, was predictive as to who would get Alzheimer’s later in life.

So when you take evidence like that and you say, when someone’s journaling, how rich is the content? What can we discern from the pattern of expressions? And do they change over time? So how did they start? And how did they change over time? Or did they stay consistent? And you can use that to infer that there’s been a change in the adaptability because they started a certain way. What has now operated on this individual that has caused them to now change the approach? And then we have to infer from that certain patterns that may give us insight into what may have been the reason for that change.

Host:Interesting. I wouldn’t have thought about that. So for the nuns it was the more detail they gave, the less likely or the more —

Dr. Tom Williams:The less likely.

Host:The less likely. So they were more vague. You were talking they had a better chance of getting Alzheimer’s when they were early.

Dr. Tom Williams:Yes.

Host:Wow. All right. I’m going to start journaling and taking detailed notes of every excruciating —

Dr. Tom Williams:Exactly.

Host:— part of my life.

Dr. Tom Williams:Exactly.

Host:It’s not going to be an interesting read but I do — yeah. I mean, that’s an awful, awful disease. But it’s interesting that you can tell it that early just based on how much detail and how much recollection you have.

Dr. Tom Williams:And if you think about what we talked about in terms of just the human’s ability to adapt, what that says is they’ve got lots of connections. And when you relate it back to what we talked about in being isolated and confined, we’re talking about removing lots of connections. And so what we want to be alert to is how does the mind attempt to adapt to it’s environment? And someone who’s more closed off, not as expressive, isn’t engaging their environment as much as the person who’s very open, engaging, seeking experiences. And from that we need to learn and identify what are the strategies that we could bring that would help counter some of the potential impact of restricting those experiences?

Host:Hmm. So I want to look ahead. I want to jump ahead to a mission to the moon or to Mars, a long-duration stay. From your perspective, what are the crew doing to maintain their behavioral performance, to make sure that they are performing and not feeling these feelings of isolation and confinement? What is part of their daily lives that will help them to be successful on these missions?

Dr. Tom Williams:That’s a really important point and question because part of what we know that helps off of us feel effective is if we have meaningful and relevant things to do each day. So part of a mission planning will have to be meaningful activities that matter, that help them feel like they’re making a contribution, because we’re taking high-achieving, high-functioning individuals and we’re going to put them on a mission. And we got to make sure that we keep them engaged on activities that they feel are worthy of their time, that help them feel as though they’re making the contribution to the overall success of the mission, and that also help them grow, that help make those connections like we were just referring to in terms of keeping the mind stimulated, to be challenging in some way, but not to the point where it frustrates, but to the point where the mind is engaged and growing, because that’s what helps us adapt each day to our environment.

And so part of what we’re looking at is what type of training might we do en route as opposed to filling all the time ahead of the mission and putting all the demands on the crew before they launch if we know there’s going to be long periods of time where they’re just transiting from Earth to, for example, Mars. How do we take advantage of that time by giving them the training that’s most appropriate and most timely for when they have to do the task? So that’s one of the approaches that we’re taking with regard to that.

Host:That’s right. So they could potentially launch from the Earth going to a long destination far away and not have all the information already packed into their brain to be successful on that mission, knowing that you have, let’s just call it six to nine-month journey to Mars. That’s six to nine months of learning that you can do, that you can be training and constantly engaging your brain to learn something new, not just a refresher, but something entirely new. That’s interesting. I wouldn’t have thought of that.

Dr. Tom Williams:And it’s a combination because it is — it’s a refreshing because some things we may have trained them to do two years before launch.

Host:Ah.

Dr. Tom Williams:And so how do we identify which of the tasks that need to be refreshed? Which are the ones that need to be learned new, that it would be okay to learn for the first time about a month before you need them? And which of the tasks that were required that you may need during the mission, during that transit time, which — when do you need which training at what sequence? And so that’s part of what we’re trying to make a determination for.

Host:Interesting. It’s good to know that we’re kind of approaching this, when we’re talking about the five hazards, we’re approaching it from all different angles. And I love how you said they’re all integrated, too. You know, we’re talking about isolation and we’re focusing a little bit on that, but in all of these studies, you know, altered gravity and radiation and being far away, all of these things are very big considerations for how to be successful in anything that you’re studying. So, Tom, I appreciate you coming on today and sharing your perspective about this idea of isolation and confinement so we can go farther into the cosmos.

Dr. Tom Williams:Great. Thank you very much for your interest and for your time and letting us share this with you.

[ Music ]

Host:Hey, thanks for sticking around. So that was Dr. Tom Williams. We talked about isolation today. And that was part two of our five-part series on the Hazards of Human Space Flight. If you have been listening to Houston, we have a podcast in order. You already listened to our talk with Zarana Patel for Radiation. That was part one. And then next week we’ll be talking about the Distance From Earth. If you want to know more about the Hazards of Human Space Flight, you can go to NASA.gov/hrp. This podcast series is — we’re working hand-in-hand with the Human Research Program to produce a lot of content around these hazards. They have a video series and their whole website dedicated to the five hazards of human space flight. So just go to NASA.gov/hrp if you want — for more information there. There are actually really cool animation videos. Otherwise you can go on social media, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, and NASA Johnson Space Center Accounts. Use the hashtag askNasa on your favorite platform to submit an idea or a question for the show so we can bring it and maybe make a whole episode out of it.

So this podcast was recorded on June 22, 2018. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Bill Stafford, Kelly Humphries, Bill Polaski, Judy Hayes, Isidro Reyna, Mel Whiting, and Natalie Gogins. And thanks again to Tom Williams for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week with part three of five of the Hazards of Human Space Flight discussing the Distance From Earth. See you then.