If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

On Episode 218, Kay Taylor describes an experiment on board the space station that allows middle school students to remotely photograph the Earth. This episode was recorded on August 30, 2021.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 218, “Eye to the Earth.” I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight. If you’re like me, you follow pretty much every astronaut on social media. And you know that when they’re on board the International Space Station they like to spend time in the Cupola, the bay window that looks down at the Earth, and they share photos of incredibly beautiful parts of the planet. You might think that they’re the lucky few who get to take such pictures, but there’s actually a way where middle school students can get their own photos taken from station. This is part of the Sally Ride EarthKAM, or Earth Knowledge Acquired by Middle school students, program. Students pick a place on the planet of their choosing and a simple set up on the space station will take the photo for them. They learn about space, geography, social science and more. On this episode, we’re going to dive deep into this program with the vice president of education at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, Dr. Kay Taylor. So, let’s get right into it. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host: Kay Taylor, thanks so much for coming on Houston We have a Podcast today.

Kay Taylor: Thanks a lot for having me.

Host: I’m excited to talk about EarthKAM. This has been a program that I have been aware of but haven’t really dove too deep into what it is and how it started, and so I’m excited to be talking to you today. But before we get into EarthKAM, I want to learn a little bit more about you: what it takes to be the person running this thing. So, Kay, tell me a little bit about yourself.

Kay Taylor: I’ve been at the, the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, I guess this is now my seventh year. Before that I had a career in journalism in mass communication, and I taught at the collegiate level for many years. But was a native of North Alabama, and it’s interesting, I kind of thought everyone grew up sitting around the table talking about NASA missions growing up, and I discovered that, that’s not the case. I am, I was born and raised in, in north Alabama. My dad worked at NASA. My mom was a teacher for many, many years. And NASA was always just sort of in the conversation. And as I went away and pursued my own career, always kept up with, with north Alabama, and particularly Huntsville, and, and NASA. And moved back to the area when my parents were a little older and, and needed a bit of assistance. And came to the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in a communications capacity, and, and then moved into the role of education. And shortly after I moved into education, NASA presented the opportunity that, that they were going to be continuing this amazing program that I had heard about called the Sally Ride EarthKAM. And what EarthKAM was, and still is today, is this amazing STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) experience aimed at middle school students, but really open to all secondary education classrooms, to take part in live science on the International Space Station. And so, the rocket center was, was very excited when NASA let us continue the work that, that literally was begun by Dr. Sally Ride of, America’s first woman in space, in, in 2016. And we’ve been, we’ve been going along and we’re in our, we’re in our second period of performance with the program, and we’re continuing to reach students, not only across the country, but around the world.

Host: That’s fantastic. And that’s really what I wanted to get into today Kay, is, is what this is, and really how it’s expanded to involve more and more people. You know I think growing up in the — you said northern Alabama, I believe that’s the Huntsville area; I want to get a sense because, to be honest, a lot of my guests are from Houston and I’m very familiar with, with what it’s like here, it’s very much the same. We have astronauts as neighbors, which is pretty cool. And it’s, you know, it’s an interesting place to grow up, and we have something, you know, like the NASA Johnson Space Center right in our backyard, and it’s, it’s very interesting. I wonder, when you talk about NASA was always a part of the conversation, I wonder, I wonder what that was like: can you paint a picture of just, how it was, you know, what led to your belief that this was a much larger, much widely known thing in the northern Alabama area?

Kay Taylor: Well at, it was just, it was our, it was the daily experience, of my dad would come in and, and he would be talking about you know the latest, latest, latest developments in the STS (Space Transportation System) program or came home and he said, you know, we’re going to build this giant telescope; it’s called Hubble. He was in the, he was in the business administration side of NASA Marshall Space Flight Center here. But we were just always talking about, you know, what the next big achievements for NASA were going to be. And I remember, you know, he, he kept me out of school when the, when the first, when the first orbiter made one of those famous 747 piggyback flights, they flew it into Huntsville so that they could test it at Marshall. And you know, we, we stood on one of the roofs of the buildings and, and watched that, you know, watched that orbiter come across, come across Marshall Space Flight Center. And I just assumed everyone was talking about it. But, but that was, you know, that was often not the case. And I think that maybe was one of the things that so attracted me to the, to the position here at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center is that the rocket center functions as the visitor center for Marshall Space Flight Center. It is our job to tell the story of Marshall Space Flight Center, and the story of space exploration. So, for me, it was just a way to, to bring what I grew up with and what I continue to keep up with, and hopefully use some of my communication skills, some of my education skills to, to make that story more widely known. And the U.S. Space and Rocket Center here in Huntsville is truly, it’s truly the front porch of Huntsville, Alabama. It is, it is where NASA’s story unfolds, it’s where we tell the story of propulsion, it’s where we tell the story of advances in spaceflight and where we’re going. It’s the home of Space Camp where, you know, each year thousands upon thousands of, of students come through and they, they learn about space exploration, they learn about our roots in space exploration, and then they, they kind of chart their own course from there.

Host: See, that’s one thing I always am so jealous of, Kay, is when I hear these stories of, of Space Camp. I just, maybe it was my lack of my own understanding. I grew up in the Pennsylvania area and so, maybe it was just something that wasn’t, wasn’t close enough, right? But it’s just, it sounds like a gateway, the way you describe it is perfect to, to understand more and get, get engaged with and maybe even dedicate a career to spaceflight. And that’s wonderful. And you mentioned in the beginning, Kay, when you were talking about your path that led you to where you are, you talk about this program and that’s really the basis of our conversation today, is this EarthKAM program. And you prefaced it with Sally Ride. You called it the Sally Ride EarthKAM. Just who is Sally Ride, and why, why is this program named after her?

Kay Taylor: Sally Ride. Sally Ride was America’s first woman in space. She was, she was an accomplished astronaut, she was a fantastic scientist, she was such an ambassador for the American space program, post-Apollo generation. I think, I think Sally embodied where space exploration quickly was headed: expanded opportunity, expanded horizons. And it was actually Dr. Ride who, who proposed the, this original program, which began as a program that was called KidSat. And she, she knew that from her own experiences in space that viewing the Earth from space often changed the astronaut’s perspective of the Earth. That suddenly, you know, you’re above the Earth and you look down and there’s this almost fragile-looking marble that contains all of life. And, and you know, many astronauts have commented on how that change in viewpoint, that change in, in altitude, if you will, changed, changed their way of seeing the Earth. And she thought, what an amazing tool; if, if we could allow students to have kind of a similar experience to that, what if we allowed students to choose how they view the Earth? And so, she was incredibly gifted, analytical mind. She said, well let’s think about this. What if we, what if we were to put a camera on the shuttle, and then as it transitioned to the, to the ISS, put a camera in space, and allow students to select where that camera photographs an image based upon where the shuttle or the ISS was passing over in orbit? And it’s, it’s a very straightforward concept. It took a little bit of engineering to develop the protocols that would allow students on Earth to create a digital file to upload to the ISS to control a Nikon camera aboard the International Space Station. But of course, because it’s NASA it all sounds easy. But it was such a straightforward concept. And so, as I mentioned, it tested as prototype on the shuttle. But it launched on the ISS in, in 2001. And since then, being hosted through UC (University of California) San Diego at Sally Ride Science, and then later coming to us, over a million images have been requested by school children from around the globe. We’ve had over a million students take part in our mission weeks through, through EarthKAM. We, you know, we’re anticipating two missions in the fall, coming up. And when I say missions, because it does require some crew time, because it does require assets on board the ISS, we run targeted mission weeks, typically four to five a year, and in that mission week students from around the world can, can log in and determine the orbit of the ISS, where it’s passing over, and select when they would like the shutter on the camera to click, thus capturing their image of a particular geographic location. So, over the lifespan of this program we’ve had students from, I believe every state and over 60 countries who have done, who have done just that: logged in, studied the latitude and longitude of the orbits as the, as the ISS passed over, and determined where to operate that camera. And then through the engineering genius of, of NASA and, and the Sally Ride program, the student then receives back the image, which are held in a database. And the student can go back and find their image and know that for a moment they operated a scientific instrument aboard the International Space Station. And as we, as we are struggling through COVID and the, and the incredible, incredible tensions that our schoolteachers and our students are facing in the, the stretching of resources, the great thing about this program is there’s no cost associated with it. And a teacher can sign up and, and the students can take more than one image. So, it’s really, it’s a great way to, to bring science into classrooms, and, and it’s at no cost to the school districts.

Host: So, it sounds like, Kay, it’s just, you just have to find wherever you are, it sounds like you have to find a link and then, do you have to submit, do you have to work with your students to submit their ideas, or their locations wherever they want to go; does it have to be that specific week, or can you do it like way in advance?

Kay Taylor: Nope, it’s got to be within the, it’s got to be within the mission weeks because —

Host: OK.

Kay Taylor: — as I’m sure you’re aware, the ISS shifts somewhat in each orbit. So, we will typically, working with the, working with some of our partners, we have some great technical partners: we have Teledyne Brown Engineering that, that is our kind of liaison between International Space Station and payloads, and the Sally Ride EarthKAM website, and then we have, we have the atmospheric sciences department at the University of Alabama Huntsville, whose graduate students and undergraduate students actually run the mission weeks for us, and then we also have great partners in the information technology and system center at University of Alabama Huntsville, who help us populate those orbits and get those published. And then a teacher logs in and registers in the, in the Sally Ride EarthKAM program at earthkam.org, and our partners at UAH send code words back to the teacher which allow the students during active mission weeks to go in and request their images. And it, so you can see, I, I said that it sounds amazingly easy, because it’s NASA and was developed by Sally Ride Science. There are several steps involved, which allow targeted controlled access to, to orbit data, which is used for each specific mission, which varies from mission to mission, and occurs within selected mission weeks. So, it’s, it’s an elegantly elaborate, yet very practical program, that again allows school children access to real time science on the ISS.

Host: I’d be so pumped if I was a middle school student and got to click the shutter button on a camera in space. That sounds fantastic.

Kay Taylor:[Laughter] Well you know we can, we can work with you. We can work with you. Because we have, while the, while it was originally targeted for middle school students, we have, we have allowed, certainly, any teacher in public education can access our program. We’re not going to say you’re a fourth-grade teacher, no, no, you cannot participate. We, we’ve tried to expand our, our opportunities because the teacher or the educator has to register. Each registration is verified by the EarthKAM team to make sure that this is for educational purposes, and we have had success with schools taking part, afterschool learning environments coming on board with us, so, we can, we can definitely work with you if you’d like to, if you’d like to take part in an upcoming mission.

Host: All right, I’ll just find the right teacher. So, so I’m stuck on the, the execution of this, right? And I got a lot of other questions, too, but, but I’m wondering during a mission week, so, say I’m a student, I’m logging on and, how many orbits can I see to make sure that if I’m interested in a particular area, how far, how far ahead in the mission week can I see to, to see maybe, maybe it won’t, I have to wait a couple of days until the orbit lines up just right where I can take a picture of the thing that I want to take a picture of. So, do you get a lot of that data ahead of time —

Kay Taylor: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Host: Cool.

Kay Taylor: Absolutely. When, when we open up a mission window, we have the orbits projected for the entire mission sequence. So, and it will be broken out on the website, literally by orbital days. So, if you look at day one, there, there may not be a clear path over the target you’re interested in, in capturing, or it may be that you look at the orbits and you say, hmm, given the orbits this time, maybe on day two, I want to capture that picture of Cairo; I didn’t think I wanted to capture an image of Cairo, but now that I look at it, it seems that’s how I want to set my target up. And you’ll be able to plug in the latitude and longitude and request that image. And that’s through looking at the, the orbital map associated with, with each mission week.

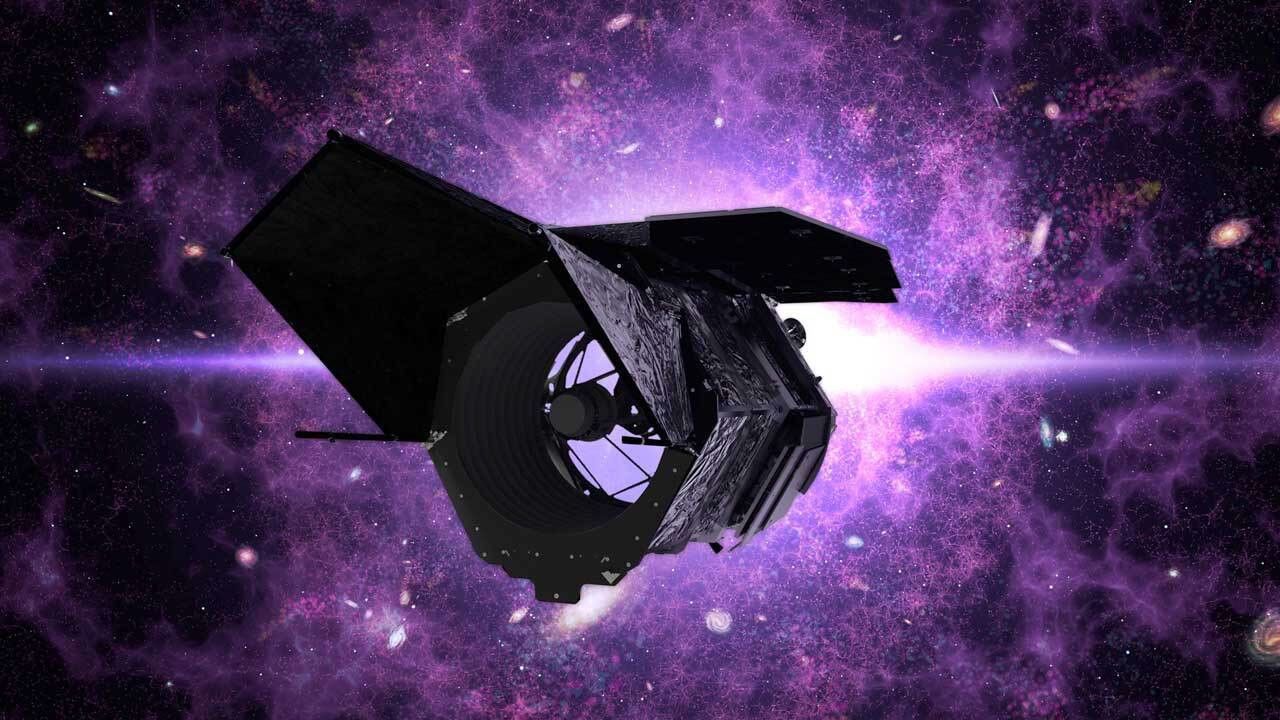

Host: I see, OK. Now, now to give a better sense of the, you know, these orbital maps and the perspective, you talked about this thing called the International Space Station and that’s where the camera is. So, so high level, what exactly is the space station and why is this a good place to put a camera to take pictures of the Earth?

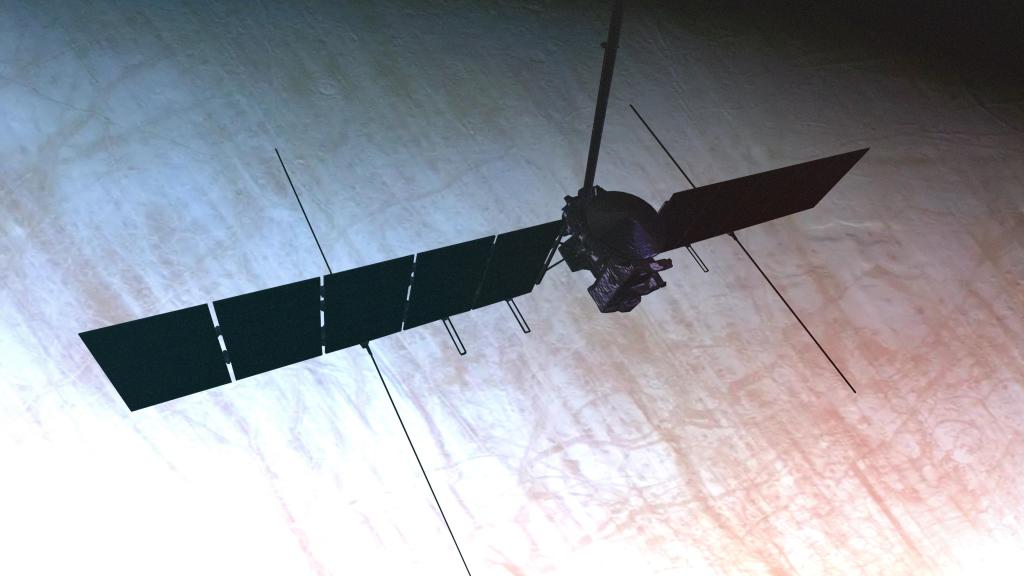

Kay Taylor: So, the International Space Station is an orbiting scientific lab that’s been just quietly going about its business, zooming around the Earth about 250 miles above the surface of the Earth, for the past 22 years. It is, it’s a remarkable accomplish, accomplishment, not only of, of science, but it’s a remarkable accomplishment of diplomacy, because of the countries involved in building the space station, assembling the space station in space, which is a pretty incredible achievement on its own accord. But the ISS is a, a multi-national lab, and the astronauts on board the ISS have conducted, for two decades, studies in materials science, studies in the development of, of crystalline structures that are leading to better medicines to help us back here on Earth, they have demonstrated how humans can live off the Earth for extended periods of time. And the ISS has really been a staging ground as we figure out where we go next in space: whether that’s the Moon, whether that’s Mars, whether that’s who knows where. The ISS has been a training ground, but it’s also been a fantastic place of pure science. And so, to have this camera on board this, this orbiting laboratory, it, it’s a, there’s a constant revolution under, underneath where you see the, you see the Earth. What better vantage point to capture the Earth than from space? And we have two lenses that are interchanged on the camera. One is a 50-millimeter lens, one is 180-millimeter lens, so there is a time, a view that is a little more enhanced than at other times, depending on the lens. But over the years with, with these thousands of image requests that have come from students around the world, we have almost a historical look at the Earth from space, that’s literally, that has literally mirrored the time that the ISS has been in orbit. So, we have a, kind of a 20-year time sequence of the Earth from space. Now, some of the images — I’m not going to lie — feature a lot of clouds, because there typically are clouds between the ISS and the Earth. But, but there are you know, there are coastlines that you can look at; by using your lat[itude] and long[itude] coordinates, you can go back through the images that we’ve posted and have collected over the years, you can go back and look at coastline changes. You can go back and look at, at how, how cities have grown. They’re, you know, if you figure out the latitude and longitude of some, some large population centers, if images have been captured, you have a, you have a “now and then” comparison, or a time lapse. So not only is it, is it the student capturing the image, but it’s then thinking about how can I take this image that I’ve captured, and images that have been captured in the past, and learn more? We have teachers from across disciplines who find value in bringing the EarthKAM program into their classroom. Certainly, learning about coordinates and learning about, and learning about geography is, is an important function with this particular program. As I mentioned, with the clouds, you get a really great view of clouds from space, which is a different perspective than you get of clouds from Earth. So there’s, there’s a tremendous utility there. And one of my favorite applications, we talk about, we talk about EarthKAM with the various professional development programs for teachers we run, one of my favorite applications is when art teachers talk about how they use EarthKAM in their classrooms, where they talk about the colors and textures of the planet, or when they, when they show these, these wonderful photos with, maybe the clouds give the appearance of the Earth below this, almost this pointillist or even like some kind of Jackson Pollock effect, that they say that using photos of the Earth as a way to inspire creativity from an artist’s eye. That’s something we don’t often think about when we’re talking about something that is traditionally a STEM education experience. But, you know, it all interconnects.

Host: Yeah, and it sounds that way. It sounds like there’s a lot of different applications to this. You mentioned, you mentioned, when you talked about the International Space Station as a platform for all this research and in this particular case, education activities, my mind started going to just how it works. I’m thinking about the technical aspect of things. You mentioned changing lenses, you mentioned a camera. How exactly is the EarthKAM, we’ll call it equipment, how is the equipment set up on the International Space Station to perform this work?

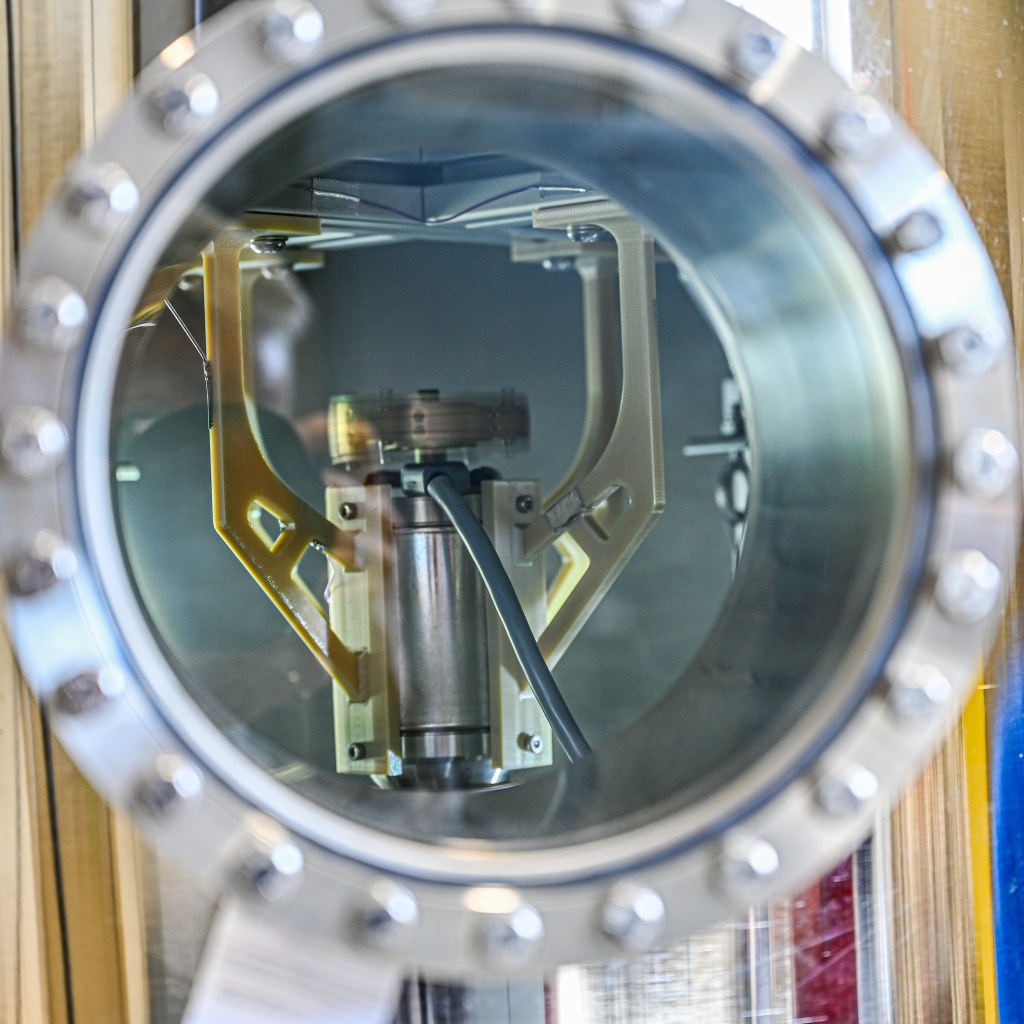

Kay Taylor: Sure. Again, here’s, here’s the elegance of simplicity. It is a camera that is connected to a laptop. And on the laptop, I mean the camera is connected by a cable to the laptop. And the, and the laptop has, has uploaded to it from here in Huntsville the camera control files, which tell the camera – which is of course an electronic DSLR (digital single lens reflex) camera — when to, I don’t want to say “fire,” I will say to depress the shutter, which causes the shutter to collapse and capture the image. The, the camera files are compiled when students go through the web portal and enter their latitude and longitude data. They can, they can include a bit more secondary data, like, like, almost like labels. They can label, you know, “Brandon’s shot of the pyramids of Egypt.” Or you know, “the Colosseum of Rome, or “the Amazon basin.” Really seeing some astounding photos of the Mississippi River flowing into the, the Gulf. And you could, you could put that tag on it, so that there’s a little, there’s a little metadata there that you can understand what it is you’re looking at. So that goes into the, the photo request. And those requests are compiled. And then they literally, the electronic file is transmitted to the, to the ISS, to the laptop on board, which then operates the shutter syncing up the latitude and longitude with the orbital passover. It captures the, captures the image and then the images are sent back, usually within a day or so they will appear populated on the website. And a student, using the code word, they can check their file and they can download the photo. They can save it on their computer. They can then use that photo…I don’t know, in a report that explains how they spent their time on the ISS, or if they are, if they’re looking to do some sort of, using that data in support of another educational program. It’s all there.

Host: So, I –

Kay Taylor: It’s literally…go ahead.

Host: I was just going to ask because I’m thinking, I’m thinking of the different shots you can get, right? When you’re executing this, and it sounds like you’re getting the images and it’s going through this web portal. You talked about changing, changing lenses at some point. Is that per mission week? So, for this mission week you get, you get this lens and then this week you’re going to get some nice close ups and then another week you’ll get, or are astronauts going on and changing lenses during, during the mission week?

Kay Taylor: The astronaut will, one of the astronauts on board the International Space Station will change out the lens, typically once during a mission, about mid-way through, we’ll go from a 180 to a 50-millimeter lens. So, in both instances, because of the, because the International Space Station is roughly 250 miles above the surface of the Earth, you’re not going to get, you’re not going to be able to get a shot of your house. You know what I’m saying? It’s, but the 180 or the 50 does change the field of view. If you’re, if you’re familiar with photography, if you’ve taken photos, you know that the smaller the number of the millimeter lens — so the 50-millimeter lens — has a wider view than the 180-millimeter lens. The 180 tends to, if you were to take pictures side-by-side, the 180 would appear to be of a smaller area by, by field of view. And you may not — I don’t think you really want to get into that at all on your podcast, because I’m kind of butchering it, and it’s kind of in the weeds. The bottom line though is at midway point in the mission week an astronaut does go in and change the lens out.

Host: Very cool. Yeah. And, and the weeds are great. We like details here and that’s for sure. So, you talked about the way that teachers and schools are able to access the EarthKAM program. You mentioned, you mentioned an EarthKAM portal. Can you talk about how that works? How a, if a teacher is interested in working with your program and, and decides to submit a registration and gets approved, how they work with EarthKAM to, to execute some of this?

Kay Taylor: Right. So once a teacher has, has registered for the program, as we get closer to mission weeks, we send out communications to let, to let the teacher know when we’ve posted the orbits. Because by, as we get, as we get closer to the mission week, we can accurately project where the International Space Station will be passing above Earth. So now it’s time for the students to look at those orbits and select their targets. When they select the target they would like to photograph, the EarthKAM program sends the teacher a list of code words, and it’s a random sequence of letters and numbers, that then the students go into the portal and enter that code word and then it also allows them to enter the latitude and longitude that they wish to target. And from there they, when they hit submit, at different points in the day during mission week, those files are uploaded to the International Space Station, and the laptop cycles through those requests and captures those images, which are then sent back to Earth and are cleaned up, and are then sent to the, our EarthKAM portal where we store them.

Host: OK. And yeah, and you already mentioned that a lot of these are searchable, so, and there’s a big repository of images already, given the amount of participation, right? You talked about, you talked about all the schools, you said every state and I think you said 60 countries was the number that you said. I wonder if you have a sense, based on your history with U.S. Space and Rocket Center, and with Earth, with this EarthKAM project, how you’ve seen the program grow and expand and reach new audiences. What have you seen just in your tenure with U.S. Space and Rocket Center?

Kay Taylor: You know, it’s interesting in looking at the data we have from the, from the missions, from, from schools around the country, and schools around the world. There are certain states where we always, we just know we’re going to have good participation from those states. And not surprisingly, you might call some of those states “space states.” Texas and Florida, California: great participation. Then you see other states that maybe you wouldn’t actually think of participating in strong numbers as well. The same goes with our international partners. There are some partners that have been long-standing participants with Sally Ride EarthKAM. Indeed, there are some schools that have been long-time participants with the program. We have tremendous participation from countries like India, Poland — Poland has been a participant with this program for the entire two decades. So, I think it’s, what we’ve been striving to do is increase the educational visibility of the program, and the educational utility of the program. And one of the things that, that has been, I think, a nice development, has been that we’ve been able to offer more students and more classes additional code words, and we’ve encouraged teachers, if we sent you enough code words for each of your students to submit an image, send us another request so we can give you more code words. And we have expanded the number of image requests and the number of images we’re capturing, because, you know, you have to realize the program is somewhat bounded because there are only so many seconds in the mission week. And when the camera is operating at, at full speed it can take, it can snap an image at about 1 to 2 seconds apart. So, you know, you can’t say well, we’ll accommodate 300 million images over the course of the week, because literally the camera can only function as quickly as the camera can function and recover. So what we’ve been, what we’ve been focusing on is trying to reach broader audiences — as I mentioned, it was originally begun as a middle school program — we’re trying to show utility for that teacher. We’re trying to show the, we’re trying to demonstrate ways that, that a first-grade teacher or a high school teacher can find value in using the science on board the ISS. So, while we’re seeking to expand reach, we’re also seeking to expand accessibility.

Host: Very good. And so, building off of that, you know, I wonder what kind of support the EarthKAM project has? I know NASA is one of the agencies that support Sally Ride EarthKAM, and that’s, that’s a very large reason why we’re discussing this today is because we’re talking about NASA’s overall efforts to, for Earth science and Earth-based projects and this is a big one because of its own unique reach. But I wonder who else is able to support Sally Ride EarthKAM and the support that you’re getting?

Kay Taylor: This is a NASA outreach program, and we manage the program. As I mentioned, we have, we have subcontracting partners in the University of Alabama Huntsville and Teledyne Brown Engineering. And then we all coordinate and work with our, our partners at NASA Marshall and NASA Johnson [Space Center] to accomplish this, this amazing outreach effort that has such global reach and is just, is just a way to, to put education at the forefront, and showcasing the importance of international participation and cooperation in space.

Host: Wonderful. Now I wonder, you, you going back to the schools for a second. We talked a lot about how the, you know, how the equipment works and how schools are engaging. But I wonder if, you know, in your years of supporting Sally Ride EarthKAM, if you’ve heard some anecdote from some teachers on how this has impacted students or different teachers lessons on how they approach unique subjects like space and coordinates and geography or Earth science, clouds, whatever it may be, I wonder if you have some anecdotes that have been passed your way on, on how this program is reaching and influencing kids and teachers?

Kay Taylor: Sure. I, I’ve had students, excuse me, I’ve had teachers tell me that students have used their EarthKAM photograph to show that there are no borders visible in space, which is a pretty profound thought. I’ve had, I’ve had teachers describe how their students were keen to look at the images to try and, and determine what effect humans are having on the Earth, again, by trying to match up as best possible an image they’ve taken with that same area taken at some point in the past. I’ve had teachers discuss how students use the, use the program to, to demonstrate real-time phenomena: we’ve had a couple of fantastic photographs of hurricanes, volcanoes, flood areas. Students are using the program to get a better perspective of their Earth in very real time. They would direct their, their photographs based upon something they had read about or heard about in the news. I know of one teacher who had a goal in their classroom to try and capture soccer stadiums of Europe. I mean, you know, so, so the topics, the topics can range. I had a teacher describe how he had used the EarthKAM as a way for his students to document life in Cuba. And this was for a high school level world civ[ilization] class. So, I love to hear how teachers have found to, to use the program, because the teachers are the real innovators. But, and whenever I see something that is truly cross disciplinary, I love it. And then, and then as I mentioned, it’s a great way to study clouds.

Host: Yeah, this is, this is absolutely fascinating just because you know, you think, you got students taking pictures of the Earth; OK, great. But what are they doing with it? And it sounds like the creativity here is, is limitless. I wonder what you learned, you know, from when you first started, how your mind has expanded, just based on some of the input and based on some of the maybe feedback that you’ve received, that can be implemented into the program going forward.

Kay Taylor: Well it’s, I think, I think what I’ve learned is that Australia just doesn’t take a bad photo, you know? It’s just, Australia is just like the most photogenic continent we have. I learned that. The blues, the blues of the water, the oranges, the reds, the greens, the grays of the land mass itself; it’s just, if, if Earth had a supermodel it’s probably going to be Australia. I think, I think for myself, I love looking at, on these static images, the movement of the Earth. And by that I mean, images of clouds, images of water, images of sand, images of coastlines, all of this that’s captured in that split second, you’re seeing, you’re seeing this dynamic, dynamic moving Earth. And there’s just, you know, there’s just, to use the phrase, there’s a vibe about it, there is. It’s like this vibration about it. I think that’s been a lot of fun. But again, I turn completely to the teachers as the innovators, because they’re finding ways to, to bring in art history, politics, you know, sociology, geology, geography; they’re the ones who really push the program. We just seek to, to give a program to them that they can come back to again and again.

Host: And that’s, that’s sort of where I want to leave off, Kay, is asking you, you know, you mentioned the growth of the program. It’s been around for a number of years, but now you’re all over the United States and all over the world. And you mentioned that you’re trying to reach audiences beyond middle school, you talked about earlier than middle school and even there are some high school applications that could be used for something, something unique as a civics class, right? But I wonder what excites you thinking about the potential of the program and going forward, and the continued use of, of this camera and these views coming from the International Space Station for years to come?

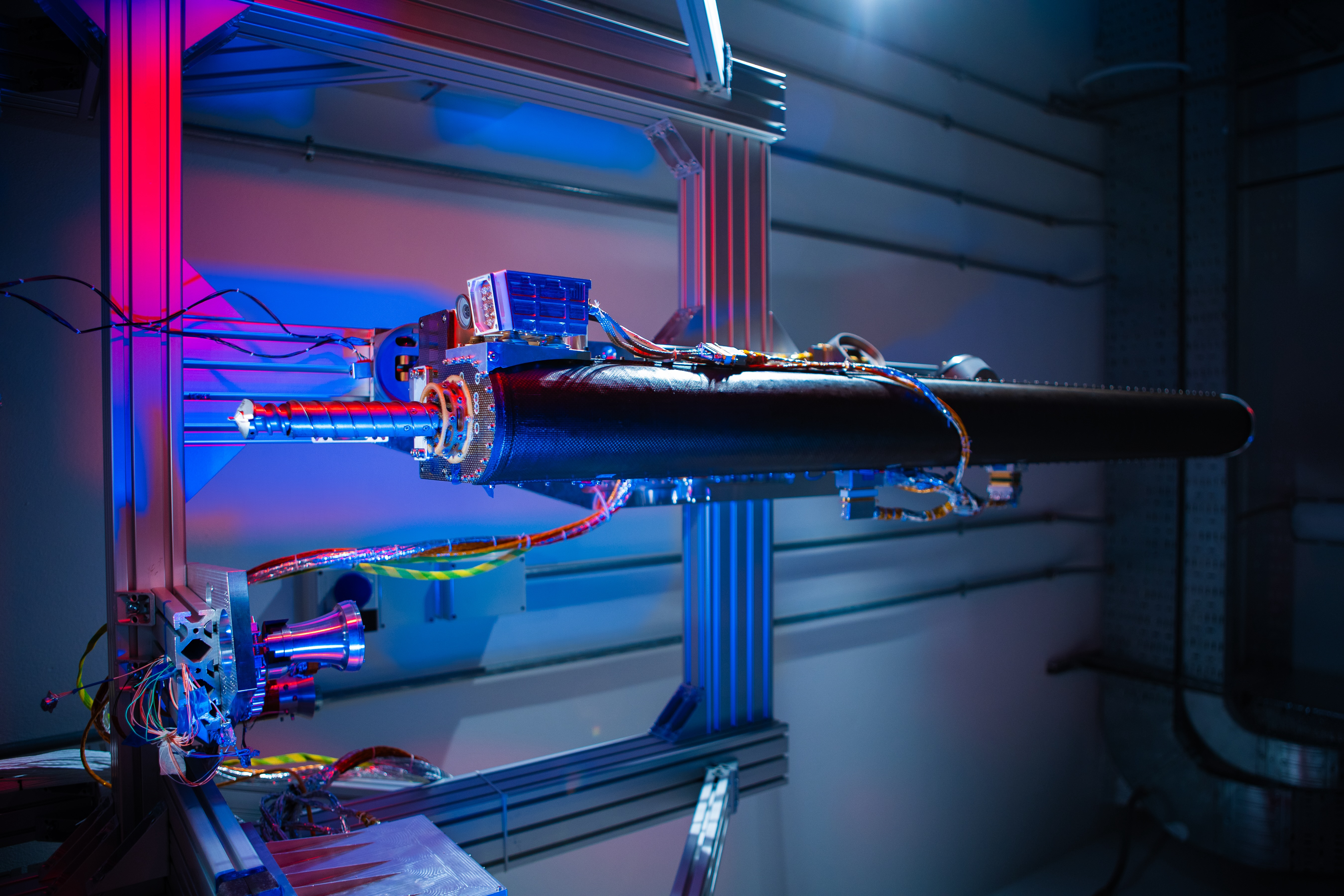

Kay Taylor: Well certainly. We’re going to be, we’re going to be shifting over to a newer model Nikon camera, and with that we’re going to have enhanced richness in the images. Because of the, because of the, the increased and improved optics, we may be able to better push a night photography experience, because currently, because it is just a standard camera loaded into, into one of the windows facing Earth, you cannot photograph in, in periods of darkness as the, as the space station flies over. The Sun has to be reflecting off the Earth for you to capture the image. With this new Nikon that we’ve got coming on board, we may be able to really push that and capture some nighttime technology with, with nighttime light, you realize your shutter speed is slowed to capture the light, and the International Space Station is trucking along at about 17,000 miles an hour. So that’s difficult. But we’re looking forward to testing it out and seeing if we can capture nighttime images of Earth, which would be a great way to study, first of all, the beauty of night lights, but it would also allow you to talk about dark skies, light pollution, it would allow you to highlight the human footprints at night on Earth. So, you know, the ability to capture night photography on Earth would be great. But also, just, just getting the newer camera aboard, we’re upgrading the camera files so we should have better performance of the program, being able to use the enhanced optics clearer, higher resolution images. That at the same time, as you know, if you increase the size of the files, you’re increasing the data needs, so we’re going to have to try and hit a fine balance between, between working the camera in tandem with a laptop and capturing larger image files. But we have, we have about 20 years of data. And you can see over time, with upgrades to the software and upgrades to the camera, you can see better images. I think when we’re able to bring this new camera online, which should be this calendar year, I think the images are only going to get better through the program.

Host: That is super exciting, Kay. And I think that’s a perfect place to leave off is just to, with the anticipation of some great technology to come. So, Kay, I really want to thank you so much for your participation in the podcast today. I certainly learned a lot about this program and a lot of the unique ways that just images from International Space Station can, can be used, and it is super-exciting to see the reach and how it’s reaching students and teachers, and getting folks involved and spreading awareness of what we do on the space station. So, Kay thanks again for coming on this podcast and sharing what you do.

Kay Taylor: I — really appreciate you reaching out. I am so glad to be a part of this incredible podcast. And I would just say for, for my final word, anyone who would be interested in joining up on our next mission, it’s earthkam.org. You can, you can work with us. We’re going to be, as I noted, we’re going to be upgrading the optics, we’re going to be upgrading the, the camera files, and we’re going to in the next year, upgrade the website, hopefully give a cleaner experience. So, come along with us and join us four to five times a year and take a picture from space.

Host: [Laughter] All right, thanks so much, Kay. Have a good one.

Kay Taylor: Thanks.

[ Music ]

Host: Hey thanks for sticking around! I hope you learned something today with Dr. Kay Taylor. I know I did. I didn’t really know a lot about the Sally Ride EarthKAM program, but now I do. It’s one of the many NASA experiments or educational programs that we have on board the International Space Station. Check them all out at NASA.gov/ISS. If you’re into podcasts, we’re just one of many at NASA. You can check them all out at NASA.gov/podcasts. We have our full collection of episodes there as well as transcripts for all of those episodes. If you want to talk to us though, we’re on the Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Just use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea for the show and make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston we have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on August 30, 2021. Thanks again to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Norah Moran, Belinda Pulido, Rachel Barry and Erin Anthony. And of course, thanks again to Kay Taylor for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.