In many ways, Mars bears remarkable similarities to Earth, but in some ways it is drastically different. Scientists often use Earth as an example, or analog, to help us to understand the geologic history of the Red Planet.

As we continue to study Mars, it is vitally important to remember in what ways it differs from Earth. One very apparent way, readily observed from orbit, has to do with its preservation of numerous craters of all sizes, which are densest in its Southern hemisphere. Earth has comparatively little preserved craters — about 1,000 to 1,500 times fewer — due to very active geologic processes, especially involving water. When it comes to impact craters, there are some things that can no longer be observed on Earth, but can be observed on Mars.

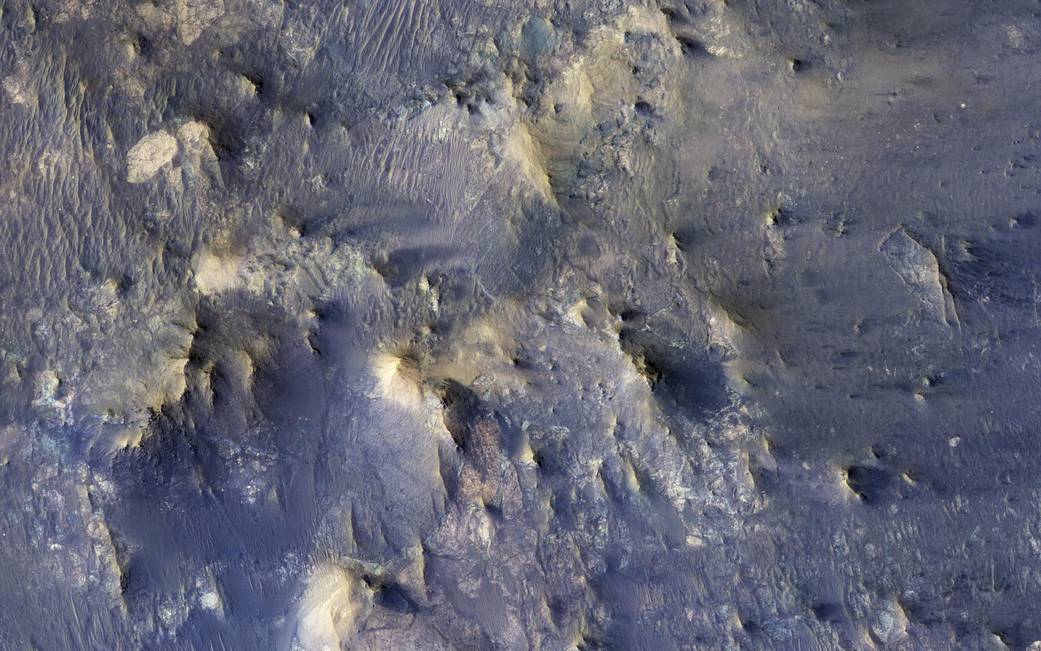

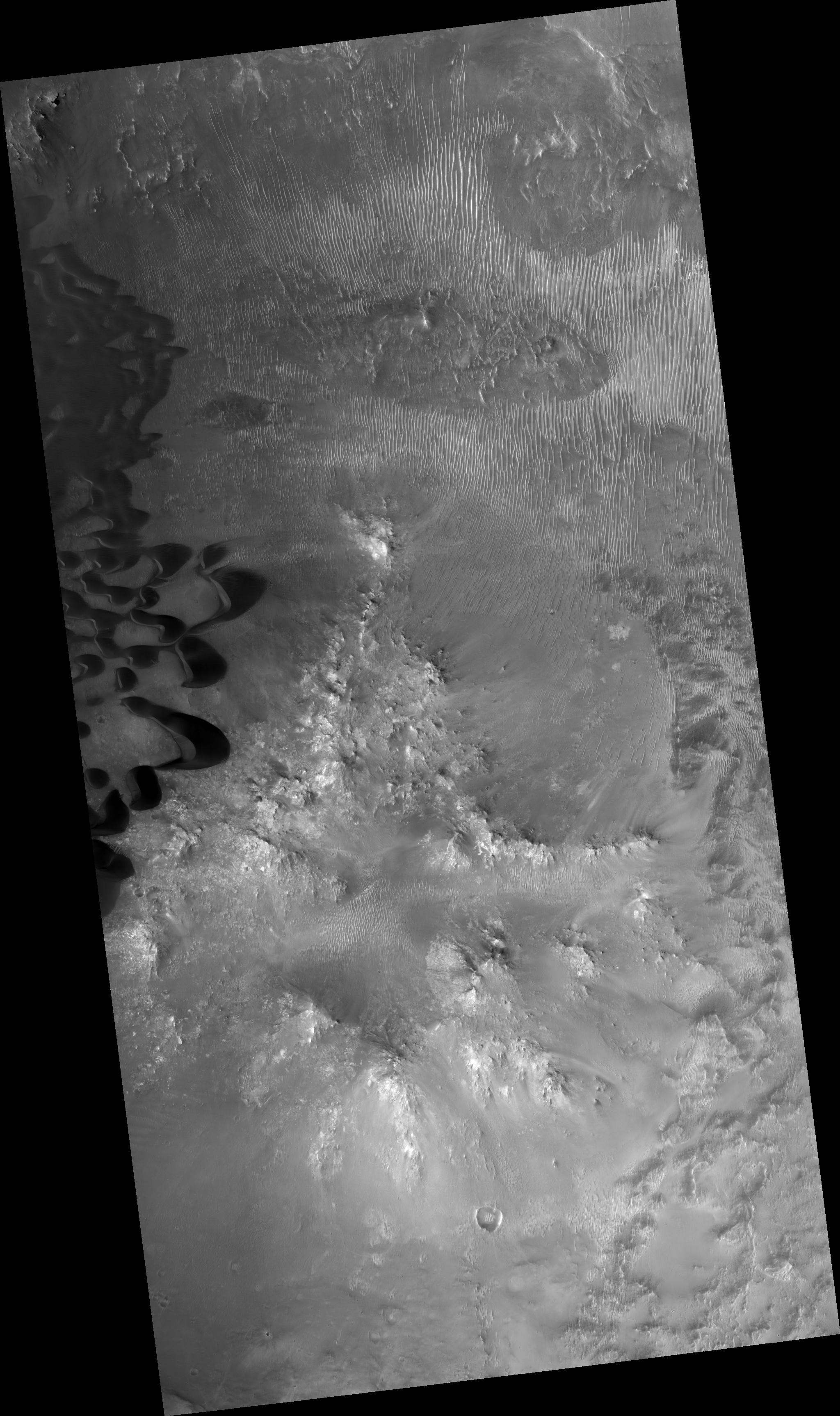

This color composite shows one such example. It covers a portion of the northern central peak of an unnamed, 20-kilometer crater that contains abundant fragmental bedrock called “breccia.” The geological relationships here suggest that these breccias include ones formed by the host crater, and others formed from numerous impacts in the distant past.

Because there are fewer craters preserved on Earth, terrestrial central uplifts do not expose bedrock formed by previous craters. It may have been the case in the past, but such craters were destroyed over geologic time.

This is a stereo pair with ESP_020043_1975.

The map is projected here at a scale of 25 centimeters (9.9 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 28 centimeters (11 inches) per pixel (with 1 x 1 binning); objects on the order of 82 centimeters (32 inches) across are resolved.] North is up.

The University of Arizona, Tucson, operates HiRISE, which was built by Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp., Boulder, Colo. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Project for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona