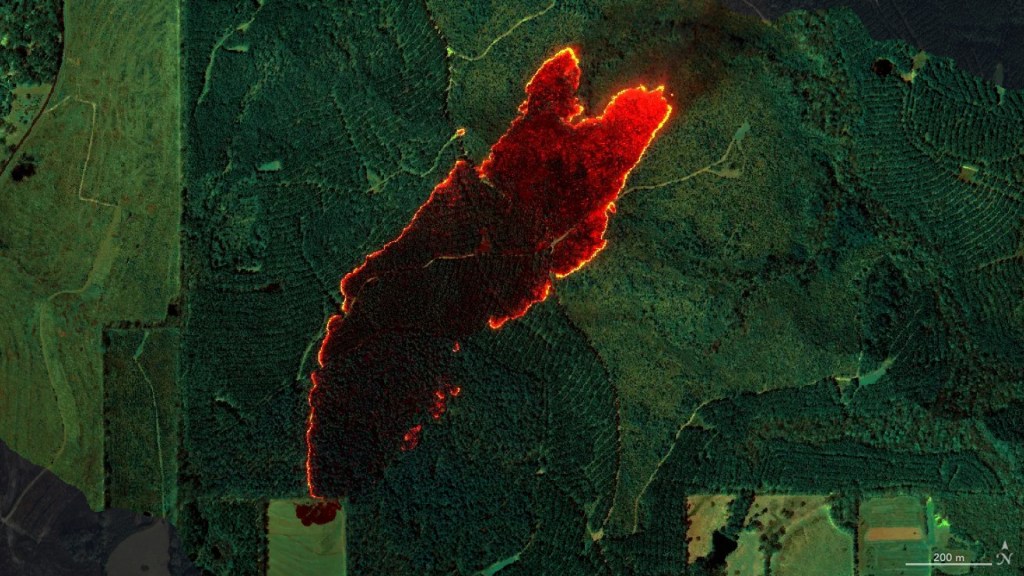

The “surfer waves” in this image, forming high above the Alaskan sky, illuminate the invisible currents in the upper atmosphere. They were measured by trimethyl-aluminum gas released during a sounding rocket launch from Poker Flat, Alaska, on Jan. 26, 2018. Scientists photograph the gas, which is not harmful to humans, after it instantaneously ignites when exposed to oxygen. The findings were published in JGR: Space Physics.

Such curling waves are a product of the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, which occurs when streams of gas or liquid pass by each other at different speeds. As the streams grate against one another, they produce characteristic curls that appear all over in nature, from the ocean’s surface to the swirling dust along Jupiter’s belt.

Researchers from Clemson University in South Carolina observed the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability shown here some 65 miles above Earth. As the waves dissipated, they created turbulence, mixing the gases above and below them. This turbulent sloshing within an otherwise stable layer of the atmosphere shows one way gases move up and down in our atmosphere. It could explain why molecular nitrogen, which is heavy, is sometimes observed much higher than it should be, while lighter atomic oxygen somehow sinks below.

Understanding how winds move through the atmosphere contributes an extra puzzle piece to the entire atmospheric system – where a slight temperature imbalance at the equator can ultimately lead to huge gusts of wind high above the arctic.

Banner Image: Trimethyl-aluminum gas clouds released by the first of three rockets launched as part of the Super Soaker campaign. The curling waves of the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability – appearing briefly in the center of the image before dissipating – may explain how gases mix in what were previously considered stable layers of the atmosphere. Credit: NASA/Super Soaker/Rafael Mesquita

By Miles HatfieldNASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.