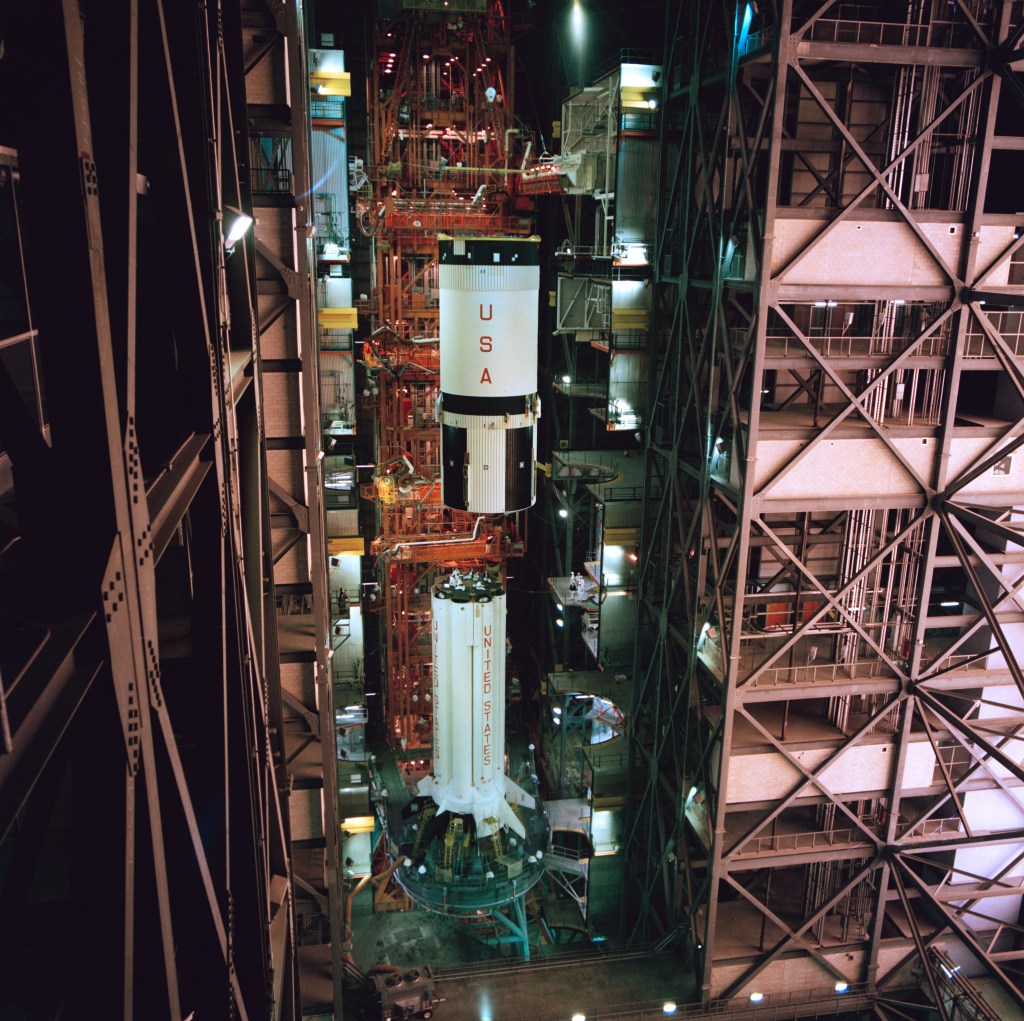

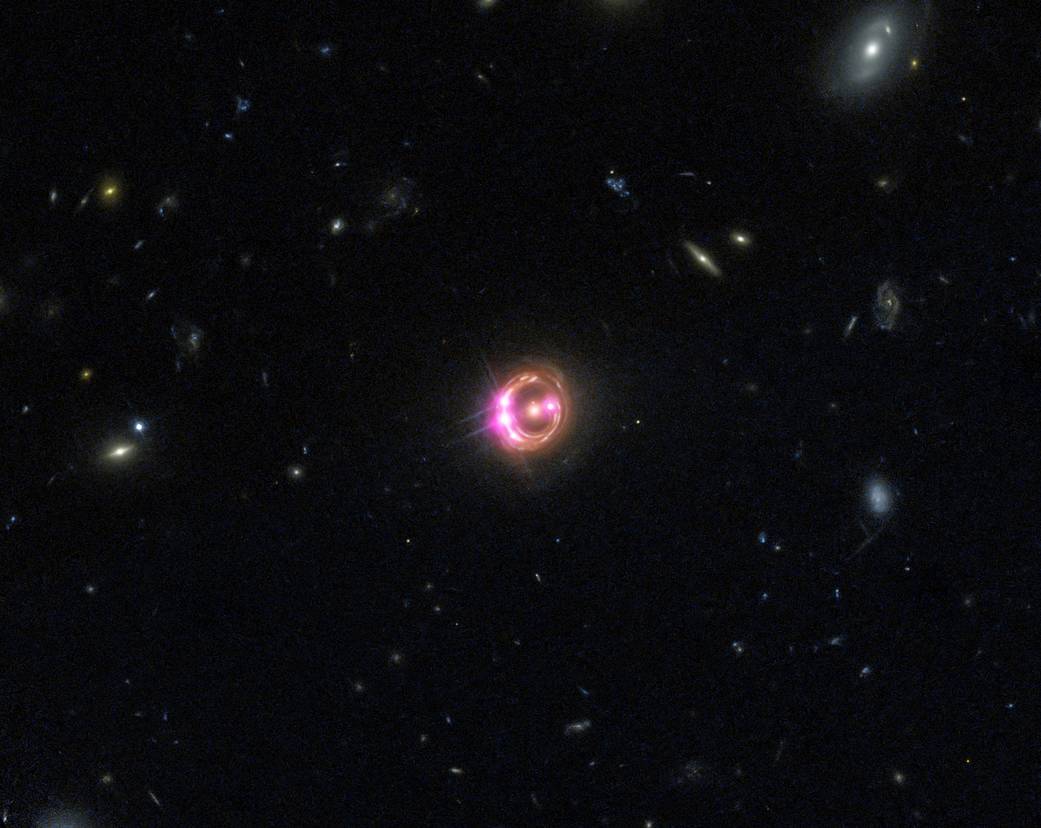

Multiple images of a distant quasar are visible in this combined view from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. The Chandra data were used to directly measure the spin of the supermassive black hole powering this quasar. This is the most distant black hole where such a measurement has been made, as reported in our press release.

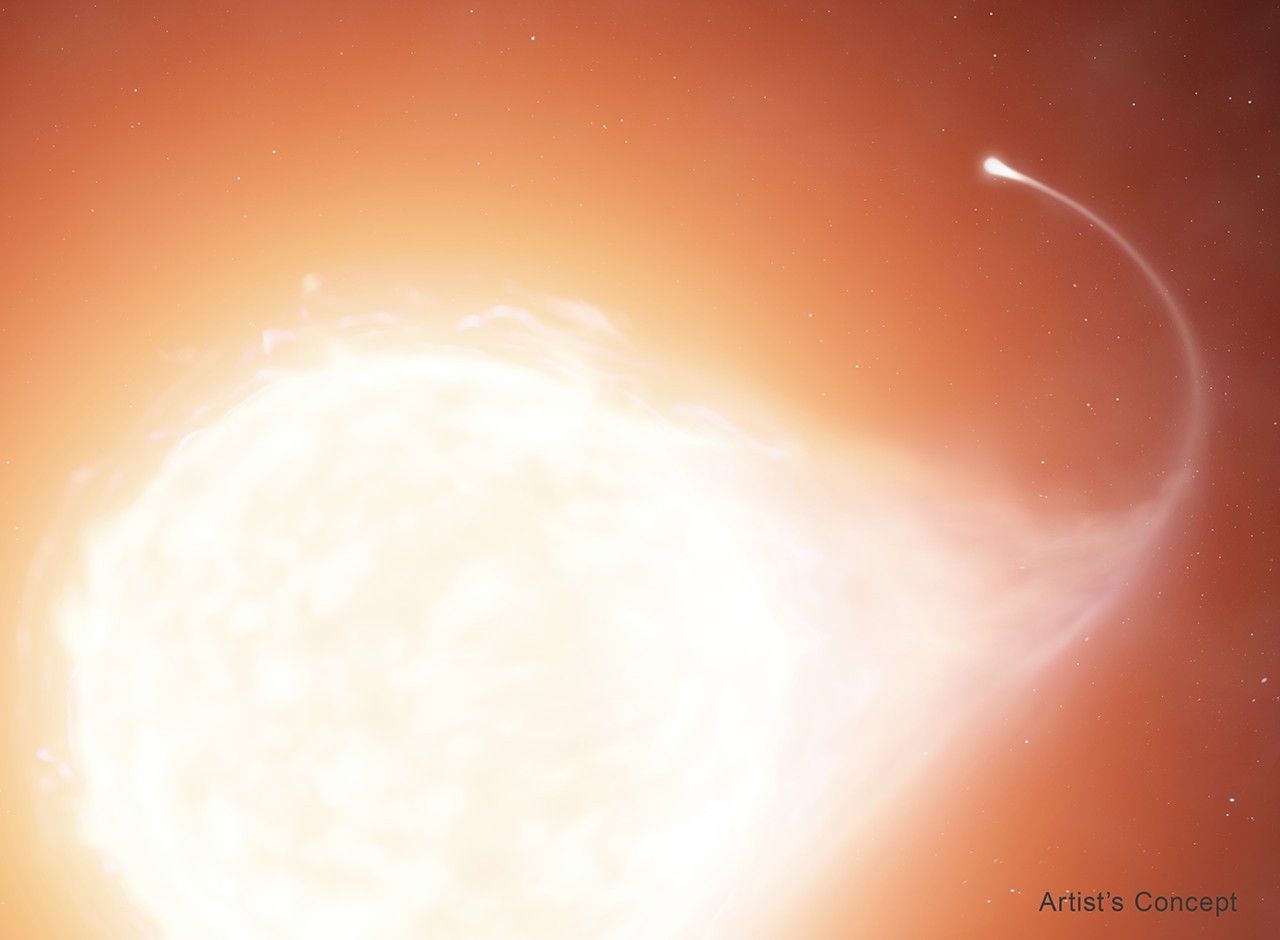

Gravitational lensing by an intervening elliptical galaxy has created four different images of the quasar, shown by the Chandra data in pink. Such lensing, first predicted by Einstein, offers a rare opportunity to study regions close to the black hole in distant quasars, by acting as a natural telescope and magnifying the light from these sources. The Hubble data in red, green and blue shows the elliptical galaxy in the middle of the image, along with other galaxies in the field.

The quasar is known as RX J1131-1231 (RX J1131 for short), located about 6 billion light years from Earth. Using the gravitational lens, a high quality X-ray spectrum – that is, the amount of X-rays seen at different energies – of RX J1131 was obtained.

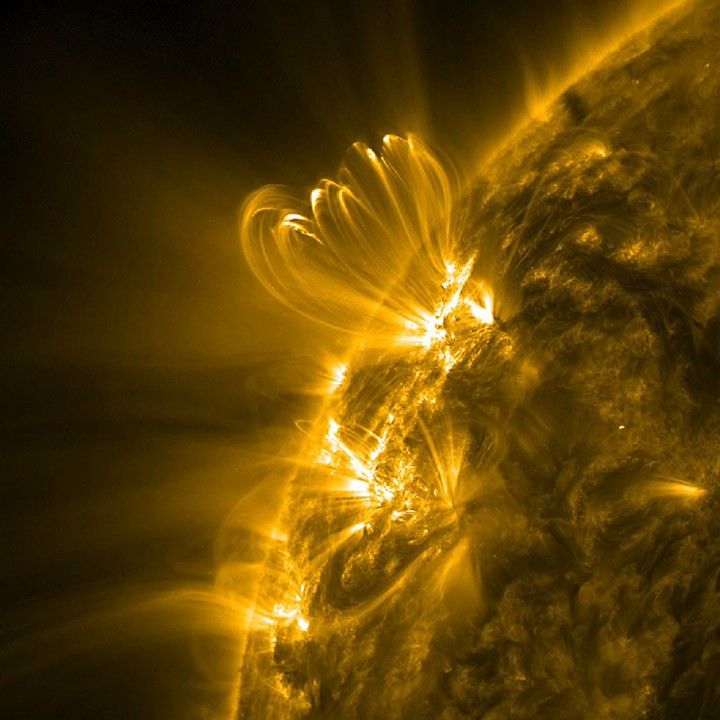

The X-rays are produced when a swirling accretion disk of gas and dust that surrounds the black hole creates a multimillion-degree cloud, or corona near the black hole. X-rays from this corona reflect off the inner edge of the accretion disk. The reflected X-ray spectrum is altered by the strong gravitational forces near the black hole. The larger the change in the spectrum, the closer the inner edge of the disk must be to the black hole.

The authors of the new study found that the X-rays are coming from a region in the disk located only about three times the radius of the event horizon, the point of no return for infalling matter. This implies that the black hole must be spinning extremely rapidly to allow a disk to survive at such a small radius.

This result is important because black holes are defined by just two simple characteristics: mass and spin. While astronomers have long been able to measure black hole masses very effectively, determining their spins have been much more difficult.

These spin measurements can give researchers important clues about how black holes grow over time. If black holes grow mainly from collisions and mergers between galaxies. they should accumulate material in a stable disk, and the steady supply of new material from the disk should lead to rapidly spinning black holes. In contrast if black holes grow through many small accretion episodes, they will accumulate material from random directions. Like a merry go round that is pushed both backwards and forwards, this would make the black hole spin more slowly.

The discovery that the black hole in RX J1131 is spinning at over half the speed of light suggests that this black hole has grown via mergers, rather than pulling material in from different directions.

These results were published online in the journal Nature. The lead author is Rubens Reis of the University of Michigan. His co-authors are Mark Reynolds and Jon M. Miller, also of Michigan, as well as Dominic Walton of the California Institute of Technology.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ of Michigan/R.C.Reis et al; Optical: NASA/STScI