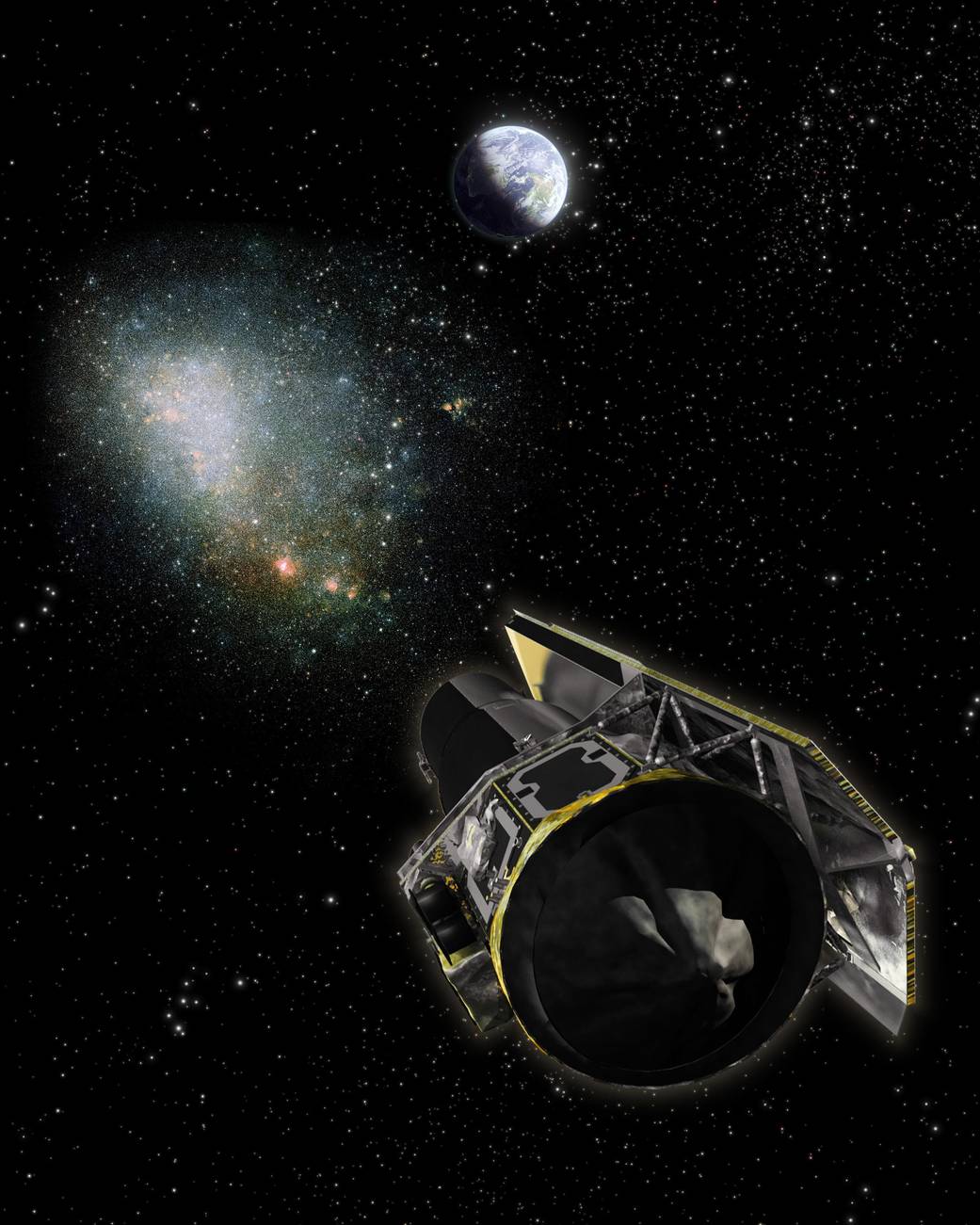

Using the unique orbit of NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and a depth-perceiving trick called parallax, astronomers have determined the distance to an invisible Milky Way object called OGLE-2005-SMC-001. This artist’s concept illustrates how this trick works: different views from both Spitzer and telescopes on Earth are combined to give depth perception.

Our Milky Way galaxy is heavier than it looks, and scientists use the term “dark matter” to describe all the “heavy stuff” in the universe that seems to be present but invisible to our telescopes. While much of this dark matter is likely made up of exotic materials, different from the ordinary particles that make up the world around us, some may consist of dark celestial bodies – like planets, black holes or failed stars – that do not produce light or are too faint to detect from Earth. OGLE-2005-SMC-001 is one of these dark celestial bodies.

Although astronomers cannot see a dark body, they can infer its presence from the way light acts around it. When a dark body like OGLE-2005-SMC-001 passes in front of a bright star, its gravity causes the background starlight to bend and brighten, a process called gravitational microlensing. When the observing telescope, dark body, and star system are closely aligned, the microlensing event reaches maximum, or peak, brightness.

A team of astronomers first sensed OGLE-2005-SMC-001’s presence when it passed in front of a star in a neighboring satellite galaxy called the Small Magellanic Cloud. In this artist’s rendering, the satellite galaxy is depicted as the fuzzy structure sitting to the left of Earth. Once they detected this microlensing event, the scientists used Spitzer and the principle of parallax to figure out its distance. Humans naturally use parallax to determine distance. Each eye sees the distance of an object differently. The brain takes each eye’s perspective and instantaneously calculates how far away the object is. To determine OGLE-2005-SMC-001’s distance, astronomers measured the microlensing event over several months with both Spitzer in space and the Earth-based telescopes. Careful analysis of the data revealed the time of the peak brightness differed slightly between the two locations.

Because astronomers knew the exact distance between Earth and Spitzer and the time lag between the peak-observed brightness, they could determine OGLE-2005-SMC-001’s speed. Using trigonometric equations and graphs to do the “brain’s” job, scientists then inferred the dark body’s location to be in the outer portion, or halo, of our galaxy.Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech-ESA/Hubble and Digitized Sky Survey 2