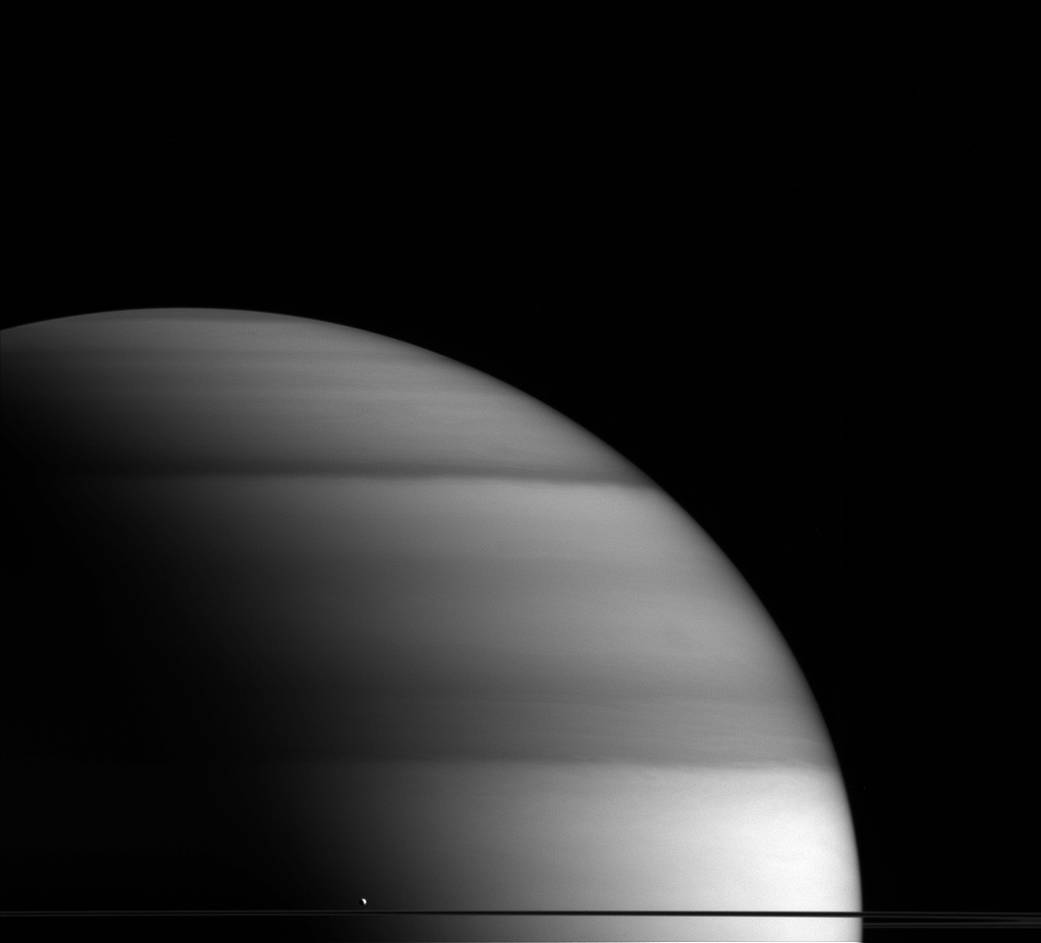

The water-world Enceladus appears here to sit atop Saturn’s rings like a drop of dew upon a leaf. Even though it appears like a tiny drop before the might of the giant Saturn, Enceladus reminds us that even small worlds hold mysteries and wonders to be explored.

By most predictions prior to Cassini’s arrival at Saturn, a moon the size of Enceladus (313 miles, 504 kilometers across) would have been expected to be a dead, frozen world. But Enceladus displays remarkable geologic activity, as evidenced by the plume emanating from its southern polar regions and its global, subsurface ocean. (For a closer look at individual jets that contribute to the plume, see PIA11688; for more on the subsurface ocean see PIA19656.) The plume, which was discovered in Cassini images, is comprised mostly of water vapor and contain entrained dust particles.

This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 0.3 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on May 25, 2015 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 728 nanometers.

The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 54 miles (87 kilometers) per pixel.

The Cassini mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (the European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and https://www.nasa.gov/cassini. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute