As humans prepare to explore more distant reaches of our solar system, the need for reliable medical monitoring and treatment increases with each mile traveled. If an astronaut were to become ill on the Moon, about 250,000 miles away, or Mars, which ranges from about 35- to 250-million miles away, immediate treatment may be necessary, and a return trip to Earth might not be possible.

On Earth, medical providers often draw blood from patients to measure their white blood cell count. It’s an important diagnostic tool that can help providers determine the cause of an illness and the response to treatment.

Although this type of laboratory analysis has yet to be accomplished aboard the International Space Station, NASA’s Human Research Program (HRP) hopes to arm future astronauts and space travelers with this crucial diagnostic capability. Currently, venous blood draws from astronauts are collected, frozen, and analyzed upon return to Earth for research purposes only.

“Getting a white blood cell count is a capability we don’t have right now in spaceflight,” said Dr. Kris Lehnhardt, element scientist for the program’s Exploration Medical Capability (ExMC) Element at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. “We have to make our astronauts more self-sufficient for long-distance flights.”

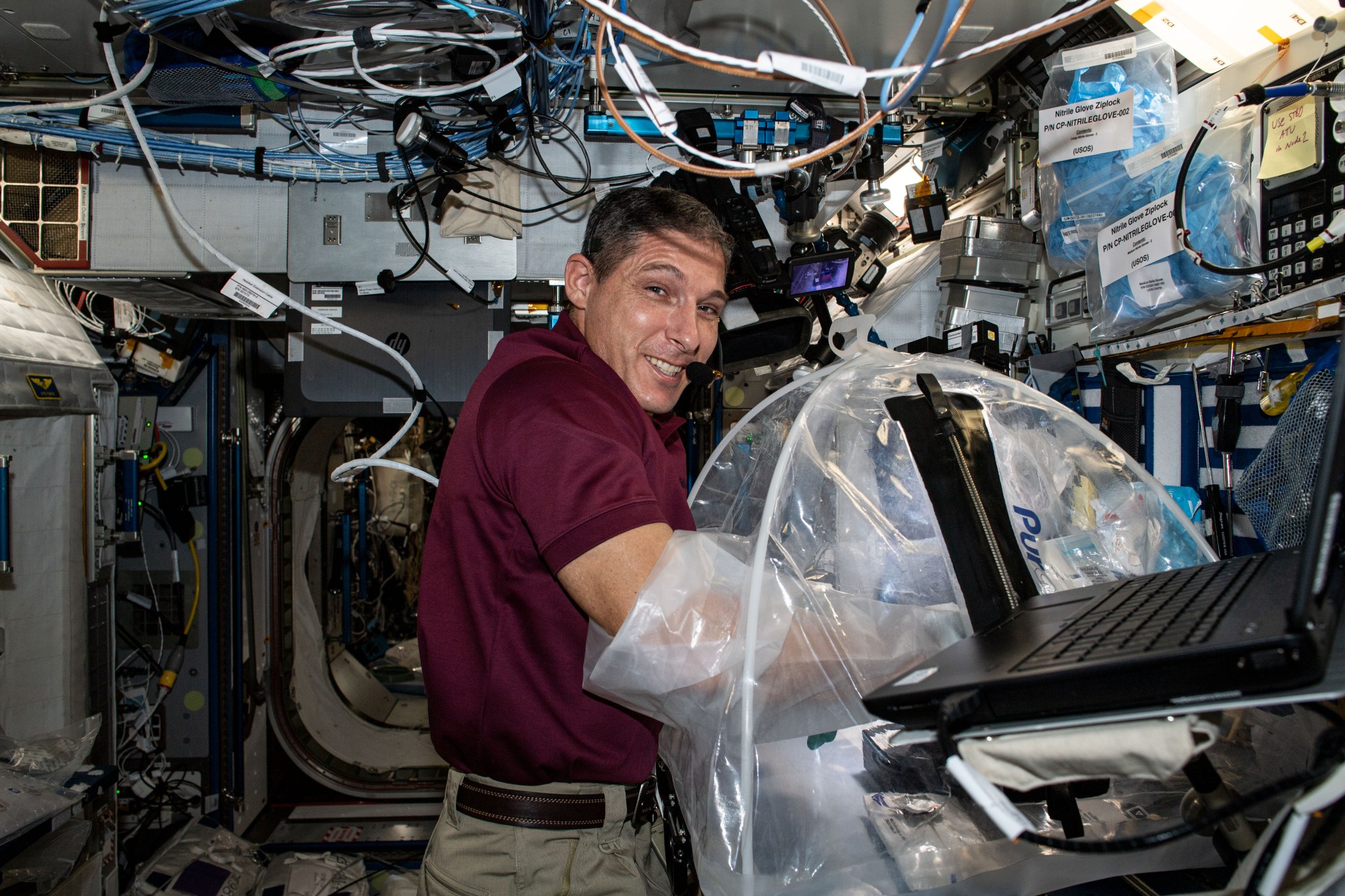

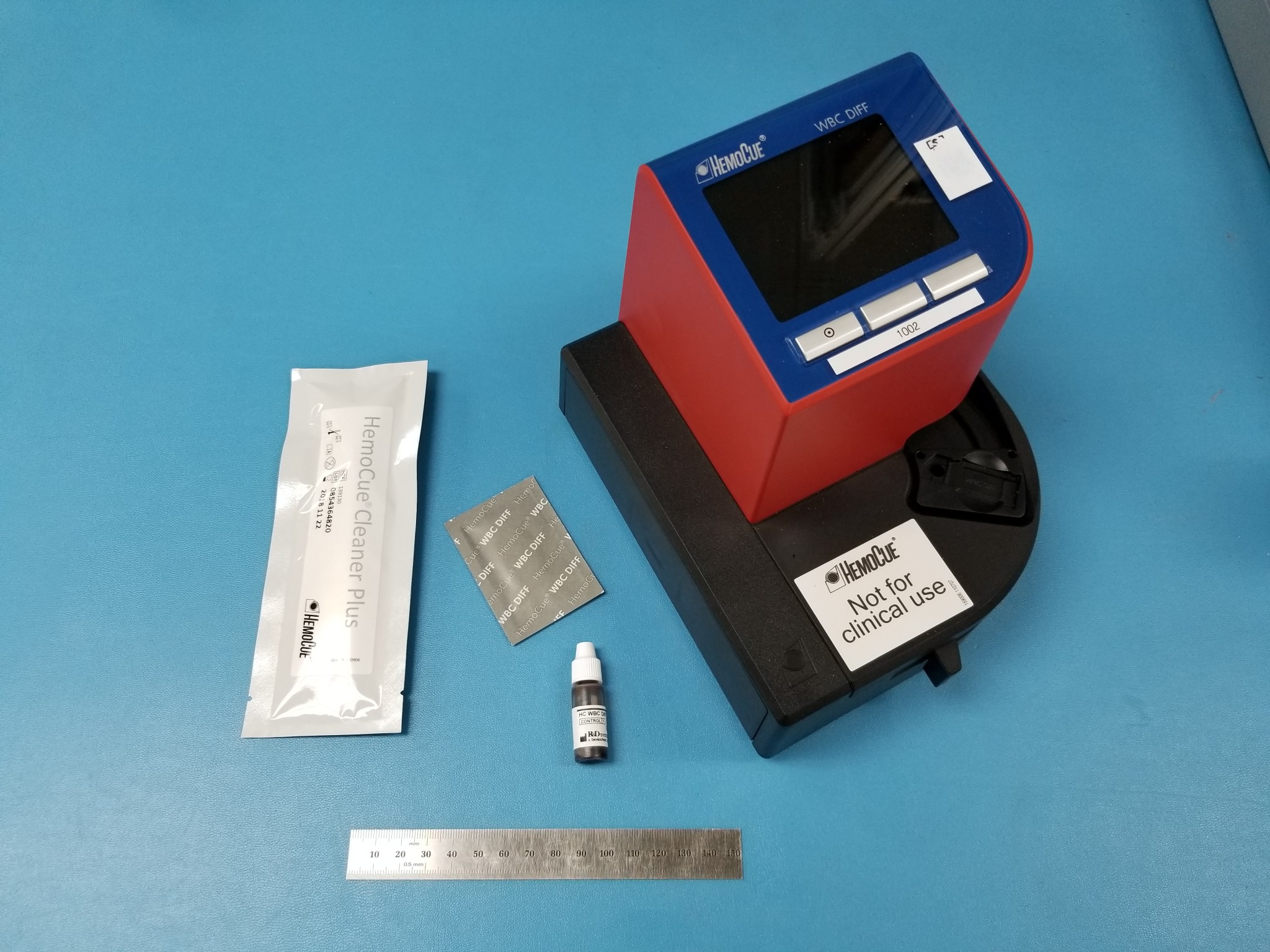

The ExMC works with other scientists to evaluate commercially available medical technology for potential use in future exploration missions. The team recently tested HemoCue – a small blood-sampling device that counts white blood cells within minutes from a single fingerstick sample — aboard the International Space Station. The demonstration showed accurate cell counts can be obtained in a microgravity environment.

Because fluid behavior is affected by microgravity, things in space don’t necessarily flow like they would on Earth. HemoCue is the first white blood cell analysis system to demonstrate that point-of-care laboratory testing is possible in microgravity. While more work needs to be done, initial HemoCue results were highly favorable. The agency plans to continue this work for consideration of inclusion on future exploration missions.

According to Kimesha Calaway, principal investigator for the demonstration and project lead at ZIN Technologies, a device such as HemoCue could be used with other indicators to diagnose and prescribe treatments for astronauts.

“Flight surgeons would run other tests to decide on treatment,” she said.

Expedition 64 astronauts Mike Hopkins and Kate Rubins supported the HemoCue demonstration by analyzing blood control solutions commonly used in hospitals spiked with a known quantity of white blood cells. The sessions were live streamed to the research team.

It was the first time NASA has ever performed real-time hematology analysis in space.

”This research is crucial because analysis of white blood cell counts would give crew members and flight surgeons insight into the severity if an astronaut were suffering from an infection or other illness,” said Gail Perusek, co-investigator and project manager at NASA’s Glenn Research Center. “It also would help them track an astronaut’s response to treatments administered during a long-duration mission.”

Dr. Brian Crucian, a NASA immunologist who has characterized alterations in white blood cell distribution and function in space station astronauts, agreed.

“The ability to perform immediate blood analysis would be a big step forward to maintaining astronaut health during deep space missions,”

Dr. Brian Crucian

NASA immunologist

The ExMC‘s mission includes advancing medical system design for exploration beyond low-Earth orbit and promoting human health and performance in space in collaboration with other scientists under the direction of NASA’s HRP. These scientists evaluate various commercially available medical technologies developed on the ground to test them aboard the space station for potential use in future exploration space missions.

Mike Gianonne

NASA’s Glenn Research Center