In an address to Congress in 1961, President John F. Kennedy challenged the nation to “land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth” before the end of the decade. With the flight of Apollo 12, 45 years ago this month, NASA achieved that goal a second time.

The crew of commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, command module pilot Richard Gordon and lunar module pilot Alan Bean were all U.S. Navy officers. Their training included simulations at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. They practiced a pinpoint landing within walking distance of the robotic Surveyor 3 spacecraft that touched down on the slope of a shallow crater in the moon’s Ocean of Storms region on April 20, 1967.

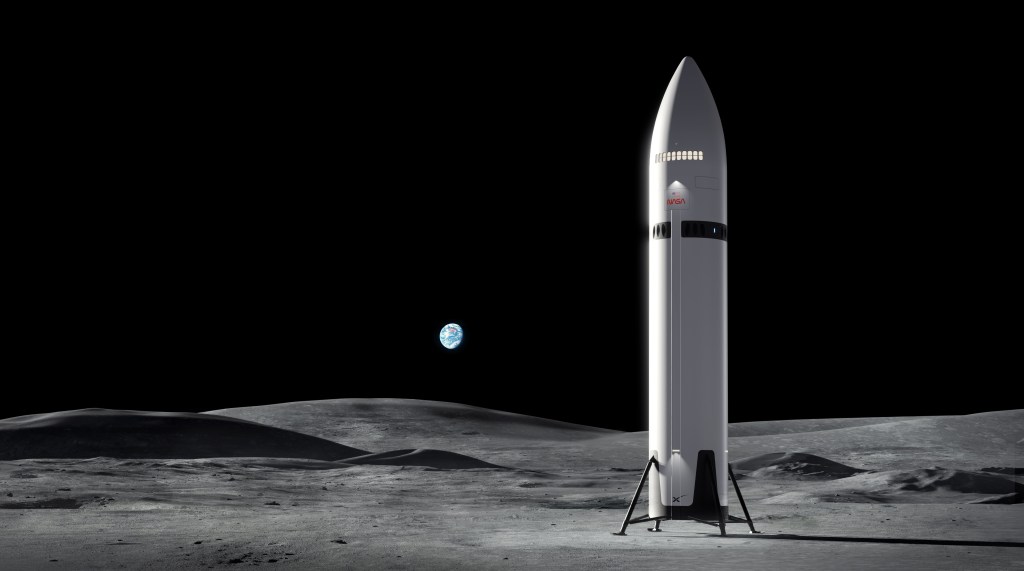

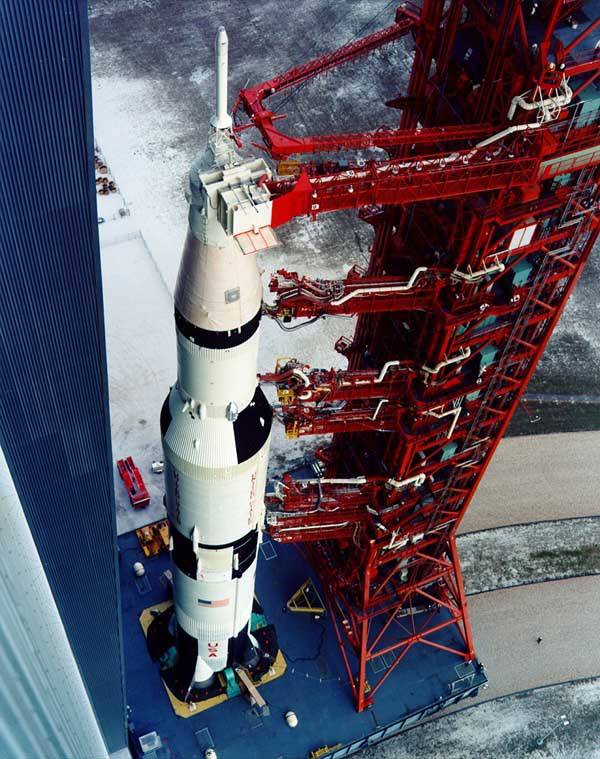

After months of processing in Kennedy’s Vehicle Assembly Building, Apollo 12’s Saturn V rocket rolled to Launch Pad 39A on Sept. 8, 1969. Liftoff took place during a rain shower on Nov. 14, 1969. At 36 seconds into the flight, the vehicle triggered a lightning discharge. All three fuel cells briefly went offline, along with much of the command/service module instrumentation. The quick action by Electrical, Environmental and Consumables manager John Aaron in Mission Control and by the crew allowed the vehicle to continue flying without further problems.

On the mission’s fifth day, Gordon remained in the command module, named Yankee Clipper, while Conrad and Bean descended to the moon’s surface aboard the lunar module, Intrepid. Bean began looking for landmarks and quickly noted they were right on target.

“Hey! Look at that crater,” he said, “right where it’s supposed to be!”

As Intrepid neared touch down, Conrad noted at about 35 feet, the exhaust from the lunar module began kicking up the regolith on the surface. It appeared to be more that that experienced by fellow astronaut Neil Armstrong, commander of the first lunar landing four months earlier.

“I think we’re in a place that’s a lot dustier than Neil’s,” he said. “It’s a good thing we had a simulation, because that was an IFR (instrument flight rules) landing.”

Instrument flight rules include regulations established to govern flight under conditions in which visual references are not possible. During a post-flight debriefing, Conrad explained that the dust was worse than expected.

“At that point, the dust was bad and I had absolutely no attitude reference by looking at the horizon (out the window).”

Minutes after the lunar touchdown, Conrad and Bean received a message from overhead.

“Intrepid,” Gordon said, “congratulations from Yankee Clipper!”

The first moonwalk began a few hours later with Conrad descending the lunar module’s ladder and making note of Armstrong’s iconic words as he first stepped onto the moon four months earlier.

“Whoopee,” Conrad said, “Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that’s a long one for me.”

He then looked behind Intrepid to see if they had, indeed, succeeded in landing near Surveyor 3.

“Guess what I see sitting on the side of the crater,” Conrad said. “The old Surveyor. It can’t be any farther than 600 feet from here. How about that?”

In history’s first attempt at precisely landing humans on another celestial world, Conrad nailed it. Images taken in 2011 by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter indicated Intrepid landed a scant 538 feet from the Surveyor.

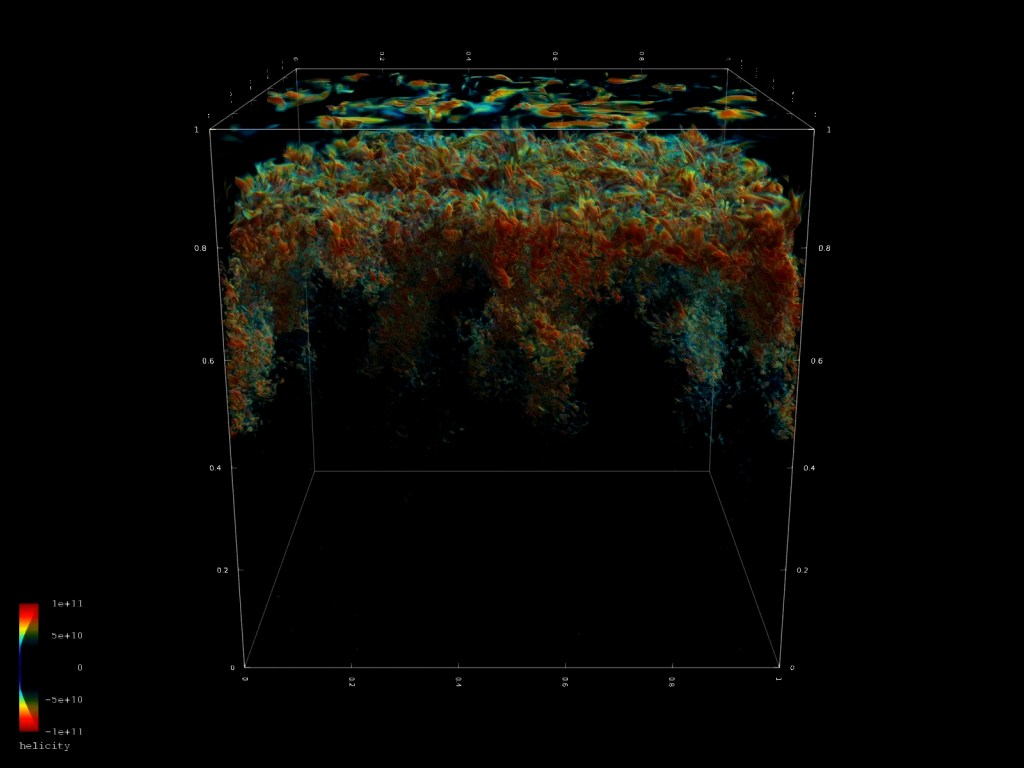

The primary mission of the first moonwalk, which lasted three hours and 56 minutes, was to set up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package, or ALSEP, which was left on the moon’s surface to gather seismic and other scientific data. Seismic readings of moonquakes would tell scientists much about the makeup below the lunar surface. Conrad and Bean also collected rock and soil samples.

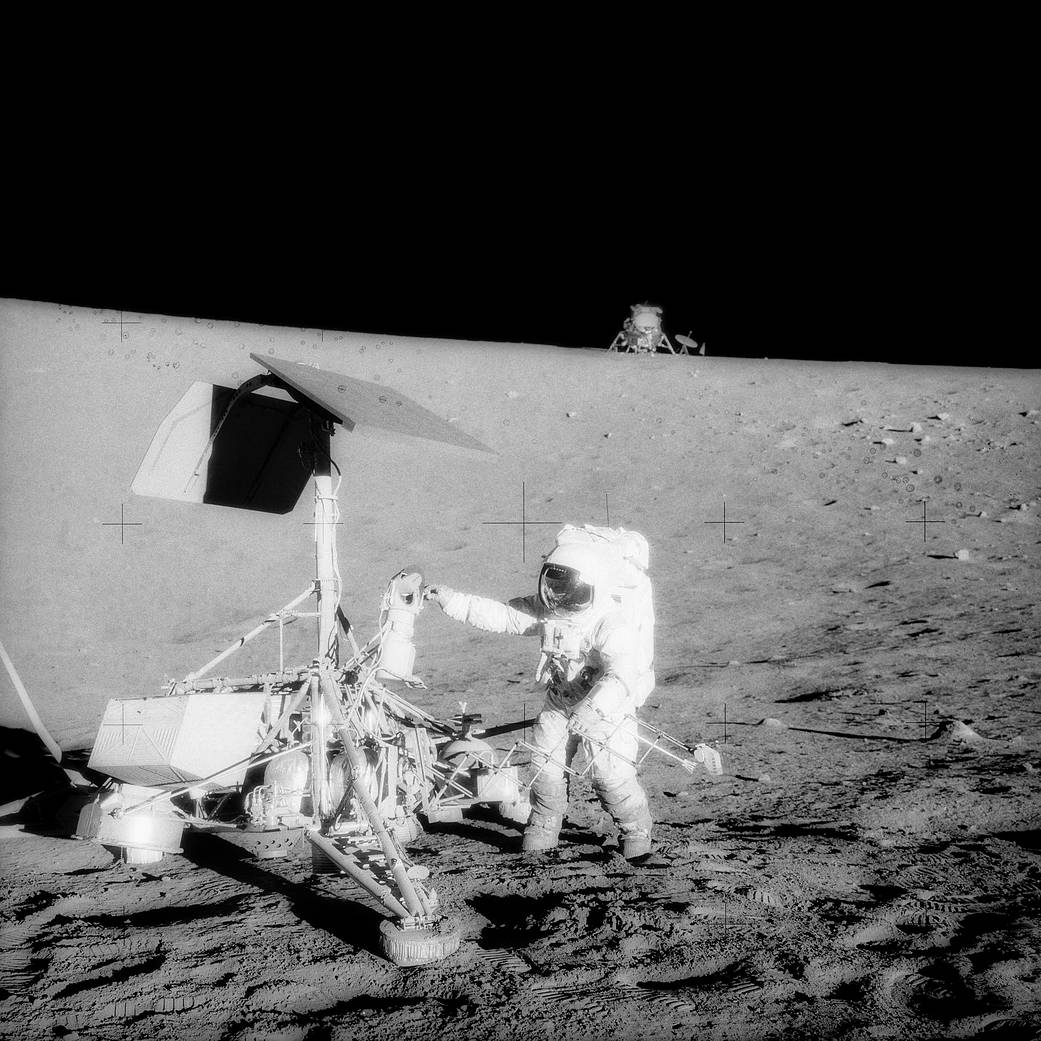

When checking the Surveyor 3 during their second moonwalk, they first believed its white color had been changed by exposure to the sun. However, upon further examination, they realized it was covered by lunar dust.

“We thought this thing had changed color, but I think it’s just dust,” Bean said. “We rubbed into (Surveyor’s) battery, and it’s good and shiny again.”

During Intrepid’s landing, the descent engine blew lunar dust onto the probe. The spacecraft was covered by a thin layer of dust giving it a tan hue.

Conrad and Bean removed Surveyor’s television camera and other parts for examination and study to learn how materials respond to years of exposure on the moon. Following three hours and 49 minutes on the surface, the explorers returned to the lunar module with parts from Surveyor and additional geological samples.

Once all the material collected on the moon was secure, Conrad and Bean began preparing for the lunar liftoff, completing 31.5 hours on the moon.

After the rendezvous with Gordon aboard the command module, the lunar collections were transferred to Yankee Clipper. Intrepid’s ascent stage was later dropped back to the moon’s surface for an early test of the ALSEP experiments they left behind. Scientists reported that the seismometers registered the vibrations for more than an hour.

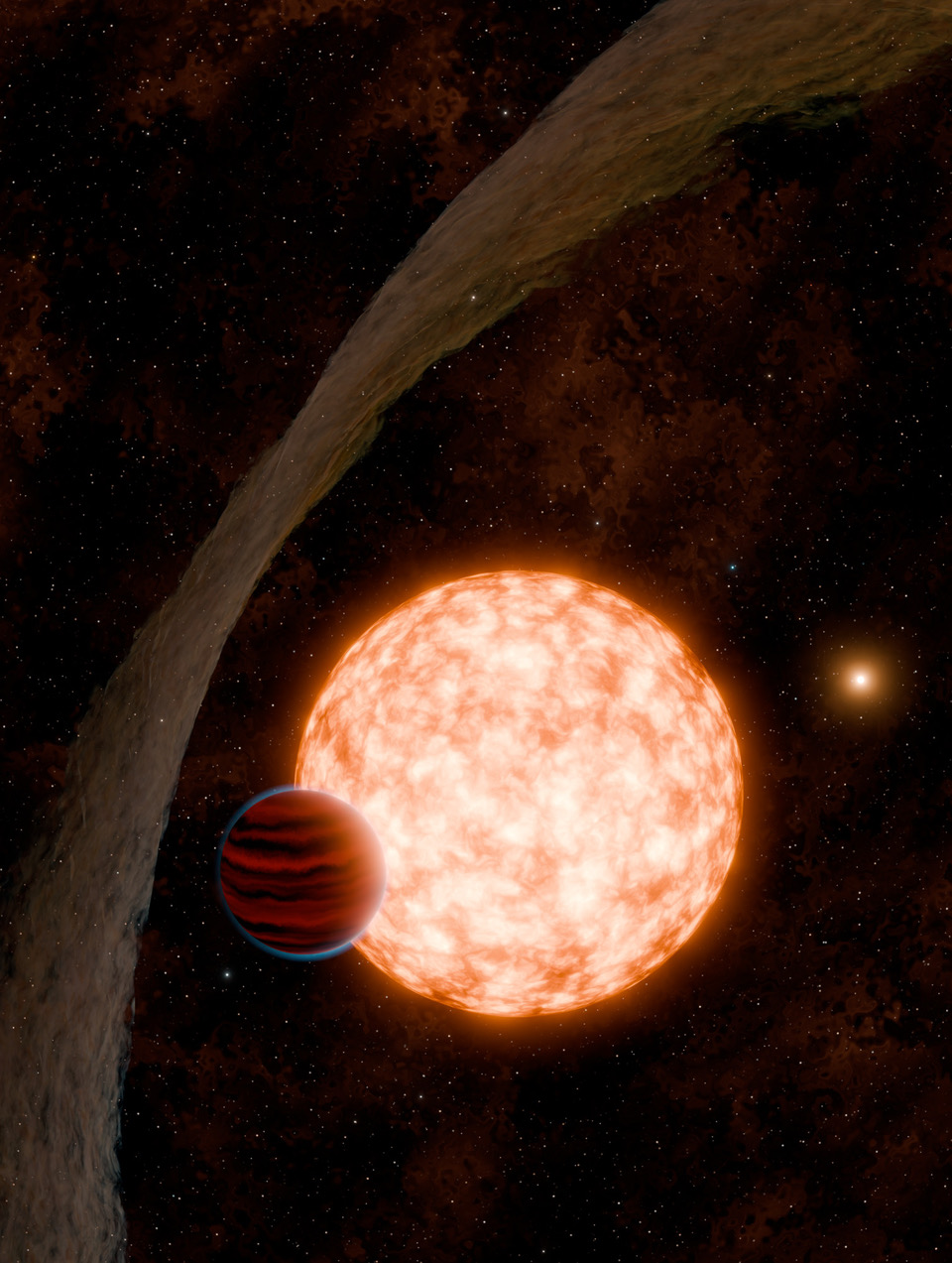

The crew remained in lunar orbit an additional day taking photographs. On the return trip to Earth the crew also photographed a solar eclipse. However this one was of the Earth eclipsing the sun.

Yankee Clipper splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on Nov. 24, 1969, and was recovered by the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.

One of the primary achievements of the second lunar landing was an exercise in pinpoint targeting. Apollo 12 succeeded in landing at its intended objective, perfecting a skill that would prove crucial for upcoming Apollo missions. Precision landings in future Apollo missions would foster exploration in regions where the lunar surface is fraught with landscapes including obstacles such as mountains and canyon-like rills. These sites provided some of the most geologically valuable findings, unlocking secrets to better understand both the moon and planet Earth.