A lot of power means a lot of heat. NASA’s future missions to explore the Moon and Mars will require enormous amounts of electrical power and hardware to support astronauts and drive new technologies. This increase in power, however, also increases the amount of heat generated—and then that heat needs to be removed so all the spacecraft systems can function.

To remove heat efficiently and reduce the mass of the cooling system, NASA is investigating new methods of transferring heat in space. One of the most effective methods for removing heat from its source is flow boiling, a two-phase process that uses the heat to boil a moving liquid until it changes it into a vapor and then flows that vapor away from the source.

The heat can also be transferred by changing a moving vapor back into a liquid in a process called flow condensation. Two-phase heat transfer systems, such as refrigerators, are very effective here on Earth, but more research is needed to understand how they will function in microgravity.

“Because a liquid/vapor mixture and interface behave differently in space, scientists need to investigate how boiling and condensation change in microgravity and obtain the data needed to apply what we’ve learned to design future heat transfer systems,” said NASA Glenn Research Center Engineer Nancy Hall.

Hall is the project manager for the Flow Boiling and Condensation Experiment, or FBCE, which will launch to the International Space Station in August, aboard Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus on the company’s 16th commercial resupply services mission for NASA.

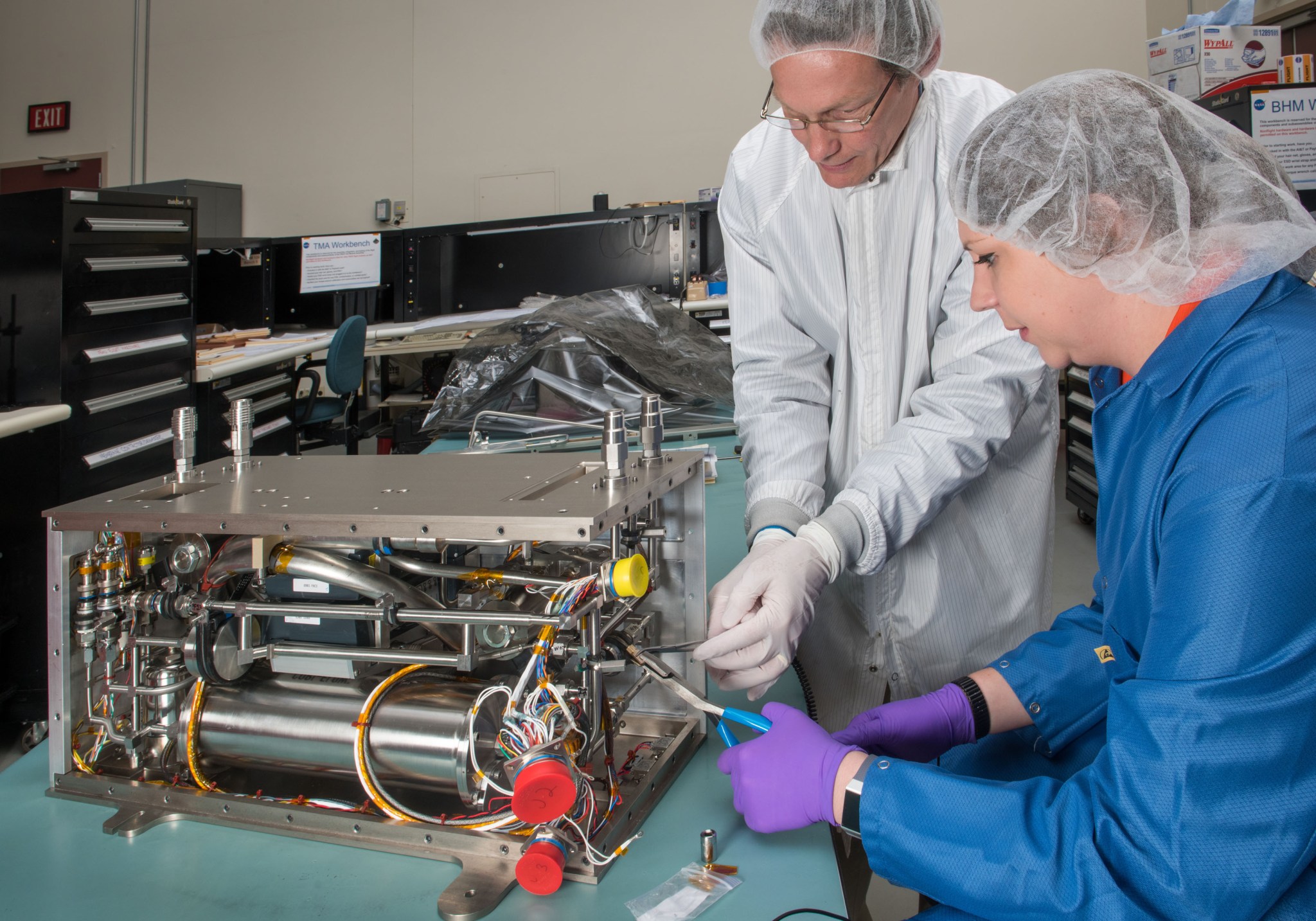

Built and tested at NASA Glenn in Cleveland, FBCE will conduct a variety of experiments on the space station to investigate flow boiling and condensation in microgravity conditions. This research is a joint effort between Glenn and the Purdue University Boiling and Two-Phase Flow Laboratory, funded by the NASA Science Mission Directorate’s Biological and Physical Sciences Division.

“When it comes to microgravity condensation and flow boiling heat transfer, data and models are extremely limited,” said Monica Guzik, FBCE chief engineer. “This experiment is critical to future NASA missions that require increased efficiency beyond the current single-phase systems.”

The FBCE consists of seven boxes, or modules. These modules are connected by cables for data communication and electrical power. Five of the modules are connected with flexible hoses to allow circulation of the fluids upon final integration. Once the hardware is on the space station, astronauts will integrate the FBCE into the Fluids and Combustion Facility Fluids Integrated Rack. After passing operational readiness reviews, FBCE is expected to become functional later this year. The experiment will then be operated and monitored by staff in Glenn’s Telescience Support Center.

“Our team has dedicated 10 years to developing this experiment,” said Hall. “FBCE is the first spaceflight hardware of this complexity built in-house at NASA Glenn in 20 years.”

Doreen Zudell

NASA Glenn Research Center

/quantum_physics_bose_einstein_condensate.jpg?w=1024)