Credit: NASA

On a recent afternoon at the Johnson Space Center, Bill Paloski, Ph.D., Director of NASA’s Human Research Program (HRP), commented on HRP’s mission to protect the health and safety of astronauts. He reflected on some of the human hazards of space, including radiation, isolation and confinement, distance from Earth, altered gravity, and hostile/closed environments.

“We still have a lot to learn about these hazards,” says Paloski. “For instance, how long does it take for space radiation to damage the human body? When you’re isolated, and can’t get home or talk to your family, how long can you stay positive? NASA’s Human Research Program exists to ensure the safety of brave people who are navigating unfamiliar territory in very stressful conditions. We need this program and its research teams to develop strategies to protect our explorers and pioneers who represent the front line of our nation’s space program.”

Paloski’s dedication to improving the lives of this “front line” has provided benefit to other sectors of the federal government, including those who serve the nation in high-risk missions and those in our military services. In recognition of these benefits, Paloski recently received the prestigious Robert M. Yerkes Award for significant contributions to military psychology by a non-psychologist.

Isolation and Confinement: Being Alone and Cramped in the Infinity of Space

According to Paloski, much of NASA’s human research in the past was focused on understanding and overcoming the effects of long-term exposure to microgravity. Scientists set guidelines for engineers to maintain a pressurized cabin for crewmembers to be able to work in the unforgiving conditions of space. Of engineering necessity, the design of crew living quarters on any space vehicle has resulted in a very small, very crowded, and often very uncomfortable habitat compared to what we are accustomed to on Earth.

As we begin to venture into deep space, new stressors – including extreme isolation and unimaginable distances from Earth – offer the potential to diminish the adaptability and resiliency of someone living in such close quarters. These stressors impact the human body and mind in several ways.

“Isolation and confinement is like being alone in a cramped space,” says Paloski. “And that feeling worsens over time. It’s an occupational hazard similar to working on a submarine. The longer and longer a person spends in that kind of environment, there is a potential for bigger and bigger problems.”

As a result, HRP has been investing significantly in studies related to individual resilience, crew composition and selection, and tools to help astronauts cope with the loneliness, helplessness, and anxiety that affect all humans separated from friends and families for long periods. This work is highly relevant to the military, especially to special operations forces, submariners, and soldiers deployed in high-risk environments, facing hostile actions halfway around the world. NASA’s research on mitigating the effects of isolation and confinement is also relevant to increasing our understanding of issues facing our aging population here on Earth. Examples of similar stressors: some elderly find themselves isolated and confined, living alone with mobility issues; others feel isolated while living in senior facilities without regular access to family and friends. NASA can both learn from, and potentially contribute insight with regard to, mitigating the stress experienced by these members of our population as well.

A Team Effort

As a respected NASA scientist who has conducted numerous studies on how spaceflight affects the inner ear, as well as how artificial gravity might be used to offset those effects, Paloski appreciates the challenges of carrying out complex human spaceflight investigations. His years of organizational leadership at the branch and division levels within NASA also provide Paloski with insight into the management aspects of research. With an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering, and advanced degrees in biomedical engineering, Paloski spent several years as a junior faculty member at the Boston University College of Engineering before joining NASA and, more recently, several more as a senior faculty member and founding Director of the University of Houston’s Center for Neuromotor and Biomechanics Research. He was drawn back to NASA to direct HRP because of the opportunity to contribute in a significant way to the success of the most challenging expedition ever planned: a human mission to Mars. He likens his current role to that of an executive producer, particularly as NASA wrestles with the challenge of astronauts living in space for months or years on end.

“My job is to work for all these people around me,” Paloski said. “Working not only with the HRP leadership team, but also for them – securing access to funds, facilities, and partnerships necessary for scientists to carry out the critical research required to ensure that astronauts will be able to stay healthy and perform their jobs in space throughout missions to destinations as distant as Mars.”

Integrating Human Research

Paloski has witnessed how investigations in one area of human research often lead to breakthroughs in other areas of science. According to Tom Williams, Element Scientist for the Human Factors and Behavioral Performance Element at the Johnson Space Center, Paloski’s support of “crossover research” has advanced the field of psychology.

Williams notes that astronauts currently working on the International Space Station spend a large part of their days connecting with people on Earth. They consult with Mission Control in Houston. They talk with scientists, doctors, reporters, students, family, and friends. That luxury won’t be available to humans traveling to Mars, where the distance makes real-time interactive communication impossible. He says astronauts like Scott Kelly who spent one year in space miss the people they know best. They often compare the experience to service members on long deployments. Astronauts also miss home in a sensory way (the smell of grass, the sight of a sunny day, the feel of their feet on the ground). When those familiar experiences are taken away, it impacts a person’s motivation. Over extended periods of time, it can even affect the ability to make decisions. Scientists are concerned that altered gravity and radiation, combined with isolation and confinement, could pose real psychological hardships, leading to further danger for the crew in space.

“The spaceflight hazards are menacingly synergistic, creating cumulative effects,” says Williams. “These combined effects are likely to pose an even graver risk to the mind and body as humans travel farther from Earth.”

To manage that risk, NASA is looking at hazards in combination as well as separately. Paloski has contributed to an integrated approach to the study of physical and mental health in space.

Impacting the Future of Health on Earth, as Well as in Space

The Yerkes awards committee recognized the significance of Paloski’s contributions as a non-psychologist in advancing research of wide relevance. According to Williams, Paloski has championed research plans that incorporate behavioral health – acknowledging potential risks to sensorimotor functions, nutritional impacts on morale, and the ability to perform under demanding conditions, especially over long periods of time. Paloski has advocated for partnerships between military, health and medical institutes, and NASA research programs. These partnerships promote human resiliency in the face of adversity.

While the Yerkes award is being presented to Paloski, he feels that the award recognizes a vast team of people.

“This recognition is a tribute to the great work that the people supporting the HRP Elements have done. Characterizing and mitigating the risks posed by psychological factors to individuals engaged in expeditionary operations in high-demand, extreme environments, as well as those experiencing isolation or confinement for long periods of time, allows us to support safe, productive human space travel,” says Paloski.

For both Paloski and Yerkes, results have demonstrated the value of psychology in support of a national level mission that includes members of our astronaut corps as well as our military service members and their families. Paloski’s advocacy for integrated research is reducing the risk posed by psychological vulnerabilities, with a goal to increase human adaptability and resiliency. Previous recipients of the Yerkes award have included Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, Senator Daniel Inouye, and Senator Elizabeth Dole.

Like Yerkes, Paloski’s award recognizes his promotion of psychology as a science of relevance to promoting the well-being of our society. Paloski’s vision has helped establish the value of psychological support to health on Earth, as well as in space.

______

In February, 2018, Bill Paloski spoke at the 2018 Investigators Workshop. To hear his remarks, click here. For further insight on spaceflight hazards, listen to Paloski’s panel discussion of Biomedical Challenges in the Humans2Mars Conference, sponsored by the National Institute of Aerospace. For information about the NASA Human Research Program, click here.

______

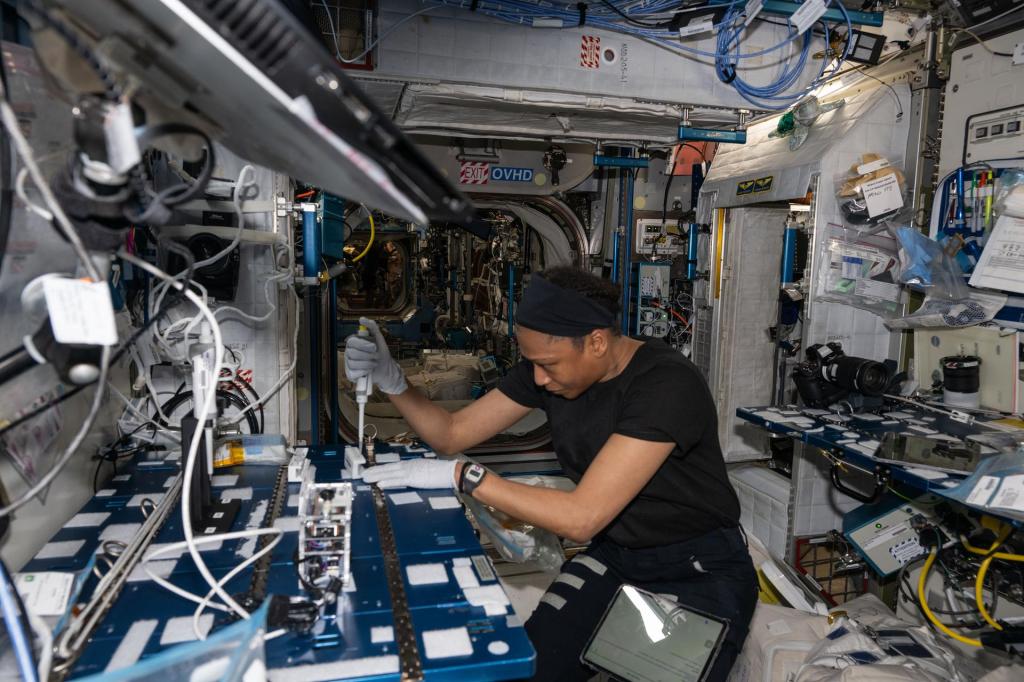

NASA’s Human Research Program, or HRP, pursues the best methods and technologies to support safe, productive human space travel. Through science conducted in laboratories, ground-based analogs, and the International Space Station, HRP scrutinizes how spaceflight affects human bodies and behaviors. Such research drives HRP’s quest to innovate ways that keep astronauts healthy and mission-ready as space travel expands to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.