Since the 1960s, NASA partnerships with commercial companies have enabled world-wide coverage of international events such as Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee and the Olympics. While global television coverage is common today, it is a technology born the day Telstar was launched 50 years ago this summer.

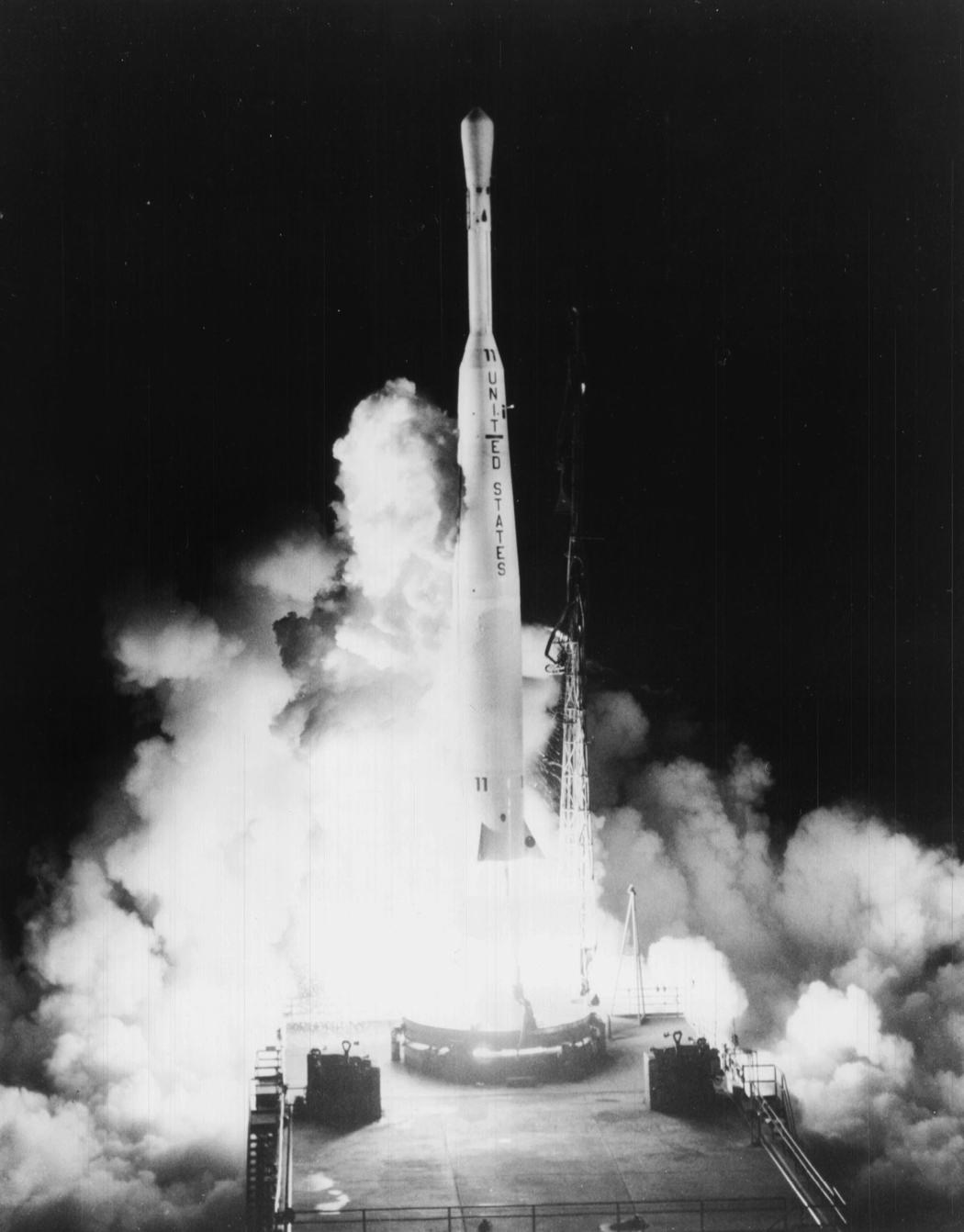

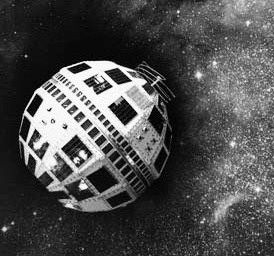

Telstar 1 was the first satellite capable of relaying television signals from Europe to North America. The 171-pound, 34.5-inch sphere loaded with transistors and covered with solar panels was placed in orbit by a Delta rocket launched from Cape Canaveral on July 10, 1962.

“Liftoff came at 2:35 a.m.,” said John Neilon, NASA’s deputy launch director for the Telstar mission. “It was also the first launch attempt,” he noted since it frequently took several tries in those days.

Once in a 3,503-mile by 593-mile elliptical orbit, the first tests con-firmed the spacecraft was functioning properly.

History was made just hours after Telstar’s launch when it relayed the first live television pictures to France – a U.S. flag waving outside the Andover, Maine, receiving station. Telstar later broadcast the first live transatlantic television seen by American TV viewers. In addition to television broadcasts, Telstar also relayed telephone calls, data trans-missions and picture facsimiles.

“We were pretty excited when it worked,” Neilon said. “Today, you expect things to work. Back then, we ‘hoped’ it would work. I was re-ally proud to be a part of it.”

Neilon was Bob Gray’s deputy director of Unmanned Launch Operations for over ten years and succeeded Gray as director in 1970. Neilon later served as Kennedy Space Center’s director of Shuttle Payload Operations, retiring in 1986 after 28 years with NASA.

President John F. Kennedy had high praise for “our American communications satellite” launched during the “heat” of the Cold War.

“This (is an) outstanding symbol of America’s space achievements,” the president said.

The international impact of technical success was immediate. A U.S. Information Agency poll showed that Telstar was better known in Great Britain than Sputnik had been in 1957.

While commercially sponsored spacecraft are now widely accepted, Telstar was the first privately financed satellite. Bell Laboratories designed and built the spacecraft which was paid for by the American Telephone and Telegraph Corp., under a NASA-AT&T agreement.

The Goddard Space Flight Center had oversight for the project for NASA.

While watching live broadcasts now seems commonplace, that convenience was not the case when Queen Elizabeth’s coronation took place in London’s Westminster Abby on June 2, 1953. American TV crews recorded the event, then developed and edited film while on an aircraft headed to New York from London. The film was aired on American television later that same day.

By contrast, Telstar led to television broadcasts as events happened on other continents.

“Telstar is the best known of all (communications satellites) and is probably considered by most observers to have ushered in the era of satellite communications,” wrote Leonard Jaffe, director of the NASA’s Satellite Communications Program in 1966.

The era of “live via satellite” TV opened opportunities for news coverage regularly from almost any place on the globe thanks to Telstar’s communications satellite successors. Elections, wars, sporting events — on any continent — are now viewed instantly around the world.

Telstar’s limitation was that it was available for broadcasts for only about 18 minutes at a time as its orbit passed over the Atlantic Ocean. The much larger communications satellites of today are always available due to a proposal by British inventor and science fiction author Sir Arthur C. Clarke.

In a 1945 article published in Wireless World magazine, Clarke proposed satellites be placed in orbit 22,300 miles above the Earth. This “geosynchronous” position allows the spacecraft to stay over the same point providing constant television communications between continents.

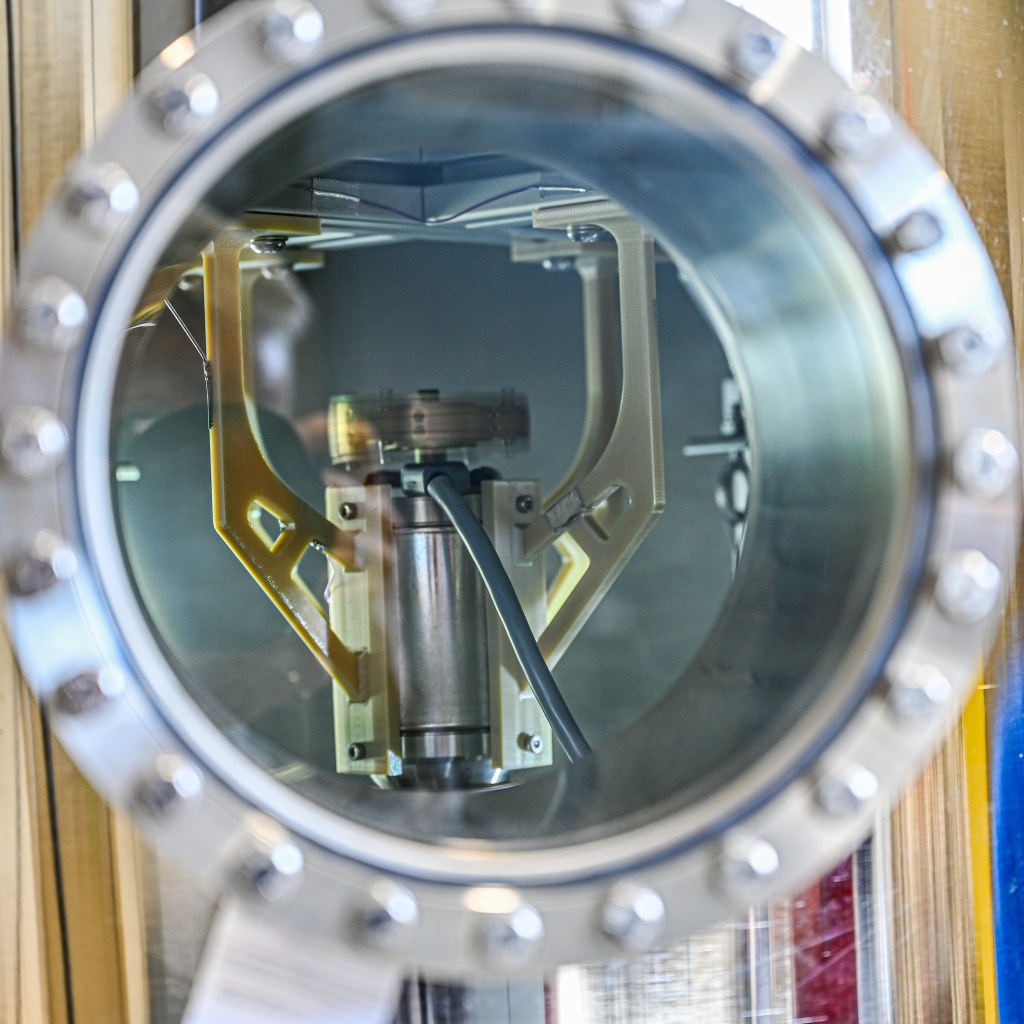

Telstar was just slightly larger than a beach ball. On the other hand, the satellite receiving stations in Andover, Maine; Pleumeur-Bodou, France; and Goonhilly Downs, Great Britain, were enormous.

“I had a chance to go up to An-dover and see that antenna,” Neilon said. “The size of that thing was really something to see.”

The Andover horn antenna was seven stories high and weighed 340 tons. Compare that to satellite antennas the size of an umbrella atop many homes bringing in signals from today’s commercial TV satellites.

When the Summer Olympics begin July 27, millions will be watching around the world “live via satellite.” That technology began a half-century ago with a beach ball-size spacecraft named Telstar.