By Linda Herridge

NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center

Forty years ago, on April 12, 1981, NASA’s Space Shuttle Columbia, attached to an external tank and twin solid rocket boosters, lifted off on the first shuttle mission, STS-1, at 7 a.m. Eastern, from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. This historic flight paired veteran astronaut and Commander John W. Young with Pilot Robert L. Crippen, who was heading to orbit for the first time.

“One of the things that [the shuttle] really allowed us to do is to fly a diverse group of people into space. We didn’t need just test pilots anymore,” Crippen said. “It opened the field in the astronaut corps and brought us a broader range than we’d ever had before. It allowed us to fly an enormous amount of people into space. Much more so than any of our previous vehicles.”

The space shuttle’s 135 missions flew 355 astronauts from the U.S. and 60 different countries.

STS-1 was Young’s fifth spaceflight. His previous missions included Gemini 3 and 10, and Apollo 10 and 16. Young walked on the Moon during Apollo 16. Crippen remembered his first flight on the inaugural space shuttle mission like it was yesterday.

It was probably one of the most exciting things in my life.

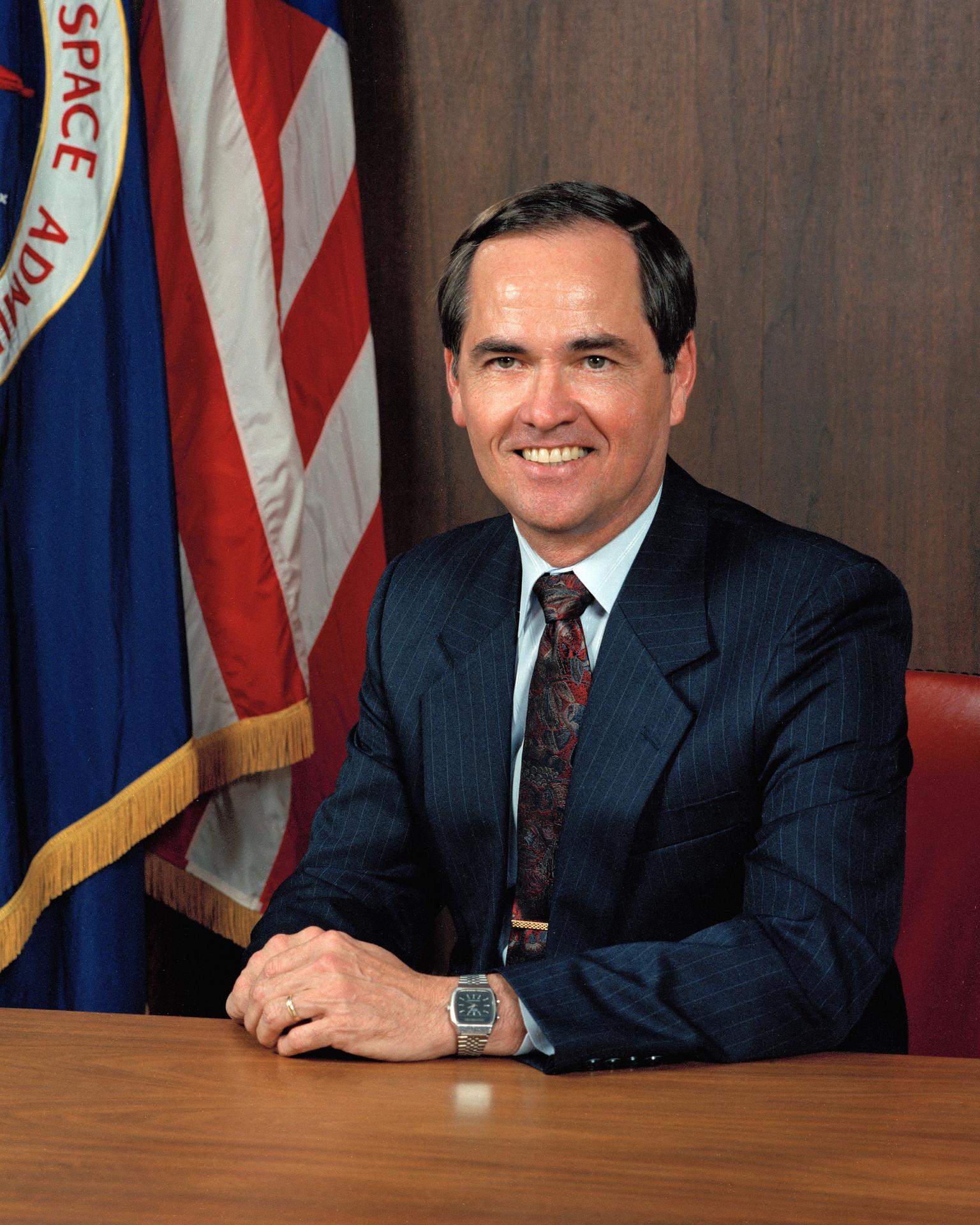

Robert L. Crippen

NASA Astronaut

“It was probably one of the most exciting things in my life,” Crippen said during a recent interview. “It was rather noisy and shaky for about two minutes after liftoff.”

STS-1 was a pure test mission to prove the shuttle system would work. The astronauts’ job was to launch, get to orbit, check out all the systems on the spacecraft, and bring it in safely for a landing.

“We didn’t carry any satellites, or things of that nature. We carried a lot of special recording equipment. Our job, basically, was just to make sure that the vehicle would do what we wanted it to do. And it lived up to all of our objectives,” Crippen said.

Payloads included the Developmental Flight Instrumentation (DFI) and the Aerodynamic Coefficient Identifications Package (ACIP) pallet containing equipment for recording temperatures, pressures, and acceleration levels on the vehicle at various points in the flight.

During the mission, Columbia orbited Earth 37 times in 54.5 hours. “Looking back at Earth was remarkable,” Crippen said.

Columbia glided to a landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California on April 14, 1981, completing its historic mission. Several days later, the shuttle was mated atop the 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), and flown across the United States for return to Kennedy. The orbiter, atop the SCA (tail number NASA 905), touched down at the center’s Shuttle Landing Facility on April 28, 1981. At the landing facility’s mate-demate device, Columbia was removed and towed to the Orbiter Processing Facility to be processed and prepared for its next mission, STS-2.

The orbiter sustained some tile damage during launch and from the overpressure wave created by the solid rocket boosters. Columbia lost 16 tiles, and 148 tiles were damaged. Subsequent modifications to the water sound suppression system eliminated the problem.

“The legacy of the space shuttle is going to be written by the historians,” Crippen said. “It flew longer than any of our other space programs (Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo) and Skylab.”

Columbia’s journey began long before its launch, when it arrived at Kennedy on March 24, 1979, aboard the 747 aircraft. It spent the next 20 months in an orbiter processing facility, completing work on its thermal protection system. On Nov. 24, 1979, Columbia rolled into the Vehicle Assembly Building, was lifted into the high bay, lowered and mated to its awaiting external tank and solid rocket boosters on a mobile launcher platform. Columbia emerged from the Vehicle Assembly Building on Dec. 29, 1980, and began the hours-long trek along the crawlerway to Launch Pad 39A, carried by the crawler-transporter.

Crippen said the space shuttle was a fantastic flying machine, but it also was a fragile one. “It took lots of TLC, and the people at Kennedy Space Center were very good at that,” Crippen said. “When Atlantis landed after the last flight, that vehicle was in as good a condition as it could possibly have been and was certainly capable of flying some more.”

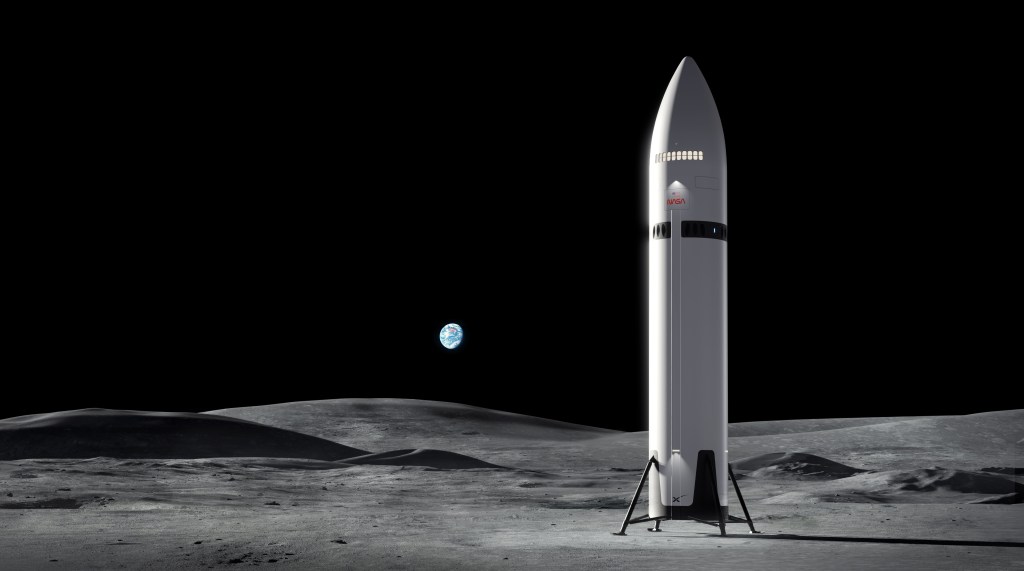

Crippen looks forward to NASA’s Artemis missions to the Moon, and then on to Mars. “We do need to get out of Earth orbit. We need to go back to the Moon. It is the right thing to do. We need to learn to live and work off this planet. There are still some great things we can do on the Moon. And then, eventually fly on to Mars.”