On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union surprised the world with the launch of a 23-inch-diameter, 184-pound ball designated Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite. For many in the United States, this news came as a profound shock and produced a considerable crisis of confidence.

The news hit especially hard in Huntsville. Dr. Eberhard Rees, who would later become Marshall Space Flight Center’s second center director, recalled how he learned about Sputnik on the evening of October 4. Both he and Dr. Wernher von Braun decided to remain after work in their ABMA offices that evening. Neither saw the need to go home since both had already planned to attend a reception on Redstone Arsenal.

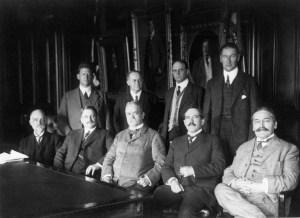

“Von Braun came over to my office and said he’d just got a telephone call of a report of the Russians,” Rees recalled. Rees also recalled how Von Braun carried news regarding Sputnik with him to the reception later that evening where Maj. Gen. John Medaris, commandant of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, was hosting Neil Hosier McElroy, who in a few days would be succeeding then Secretary of Defense Charlie Wilson.

Armed with the news about Sputnik, Von Braun decided to use the reception as an opportunity to impress on McElroy ABMA’s readiness and willingness to use the Jupiter-C to place America’s first satellite in orbit.

Peter T. Chew, writing in the National Observer five years after the event, recounted von Braun’s comments to McElroy at the reception: “Mr. Secretary. When you get back to Washington, you’ll find that all hell has broken loose. We can put up a satellite in 60 days—once you give us the go-ahead.”

General Medaris interjected: “Make it 90 days, Wernher.”

“Okay, make it 90 days.” said Von Braun.

Referring to the confidence he and others at ABMA had regarding Jupiter-C, Rees stated that, “We could have beaten the Russians easy by half a year or so.” Like Dr. Rees, most Americans had assured themselves of a perceived scientific and technological superiority over its Cold War enemy. With their confidence shattered by the success of Sputnik, Americans demanded a response to restore the balance of power.

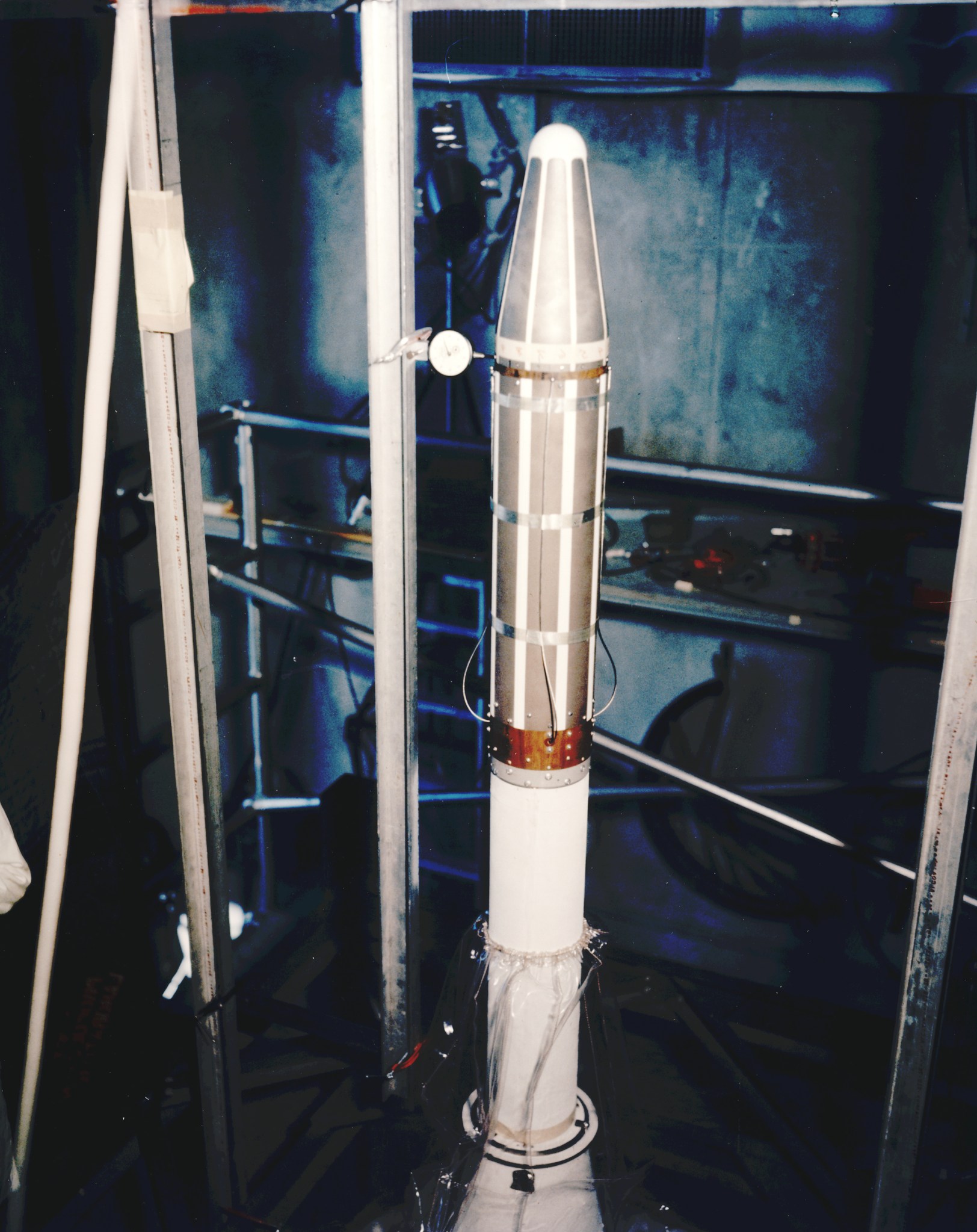

Back in Huntsville, the Army’s rocket team lead by Major General John B. Medaris and Dr. Wernher von Braun argued that their own Jupiter-C (Juno I) rocket was capable of that response. But it was the launch of the 12-pound Sputnik 2 carrying dog “Laika” in late 1957 and the public failure of the Navy’s Project Vanguard launch on December 6, 1957 that compelled the Department of Defense to turn to the Army for an answer.

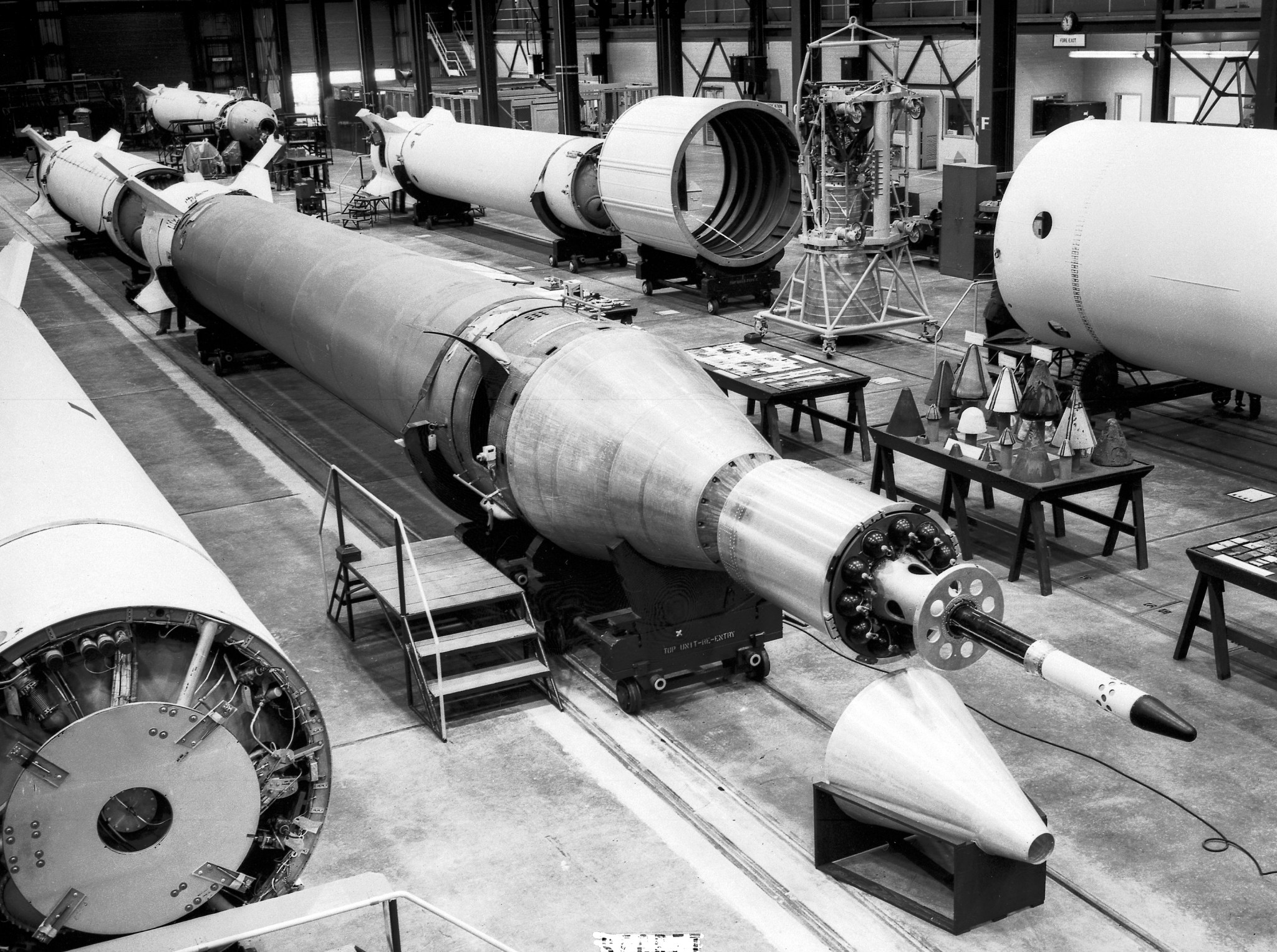

Back in 1954, the Army had proposed the use of the Redstone to launch an Earth-orbiting satellite as part of Project Orbiter. Despite the decision to go with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) proposed Project Vanguard, Dr. Wernher von Braun and his fellow ABMA rocket scientists in Huntsville continued to expand the Redstone into the modified Jupiter-C version, fired for the first time in September 1956. The ABMA group quietly placed the hardware in storage, maintaining it at a high state of readiness.

In a February 1972 letter to von Braun, Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger remembered the time leading up to the launch of Explorer I when a “distinguished gentleman” from Washington visited Redstone to discuss the status of the rocket program. During the visit, the visitor issued a stern warning to the team saying, “Wernher, now listen. There is much talk about satellites these days. Satellites are not for you! I want you to keep your hands off. Do you hear me?” Stuhlinger then recalled a latter “desperate telegram” from the same visitor asking:

“Can you launch a satellite quickly?” It so happened you could. Following your own built in guidance system, supported by good friends who shared your enthusiasm, you had been working on that satellite and its four-stage rocket already for a year, and you were prepared to put it in orbit when it was needed.”

To accomplish the mission, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) teamed with Dr. William H. Pickering, the Director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California and Dr. James van Allen of the University of Iowa, whose “Proposal for Cosmic Ray Observations in Earth Satellites” was configured for both the Vanguard and Jupiter-C.

At 10:48pm on January 31, 1958, the Jupiter-C (Juno 1) lifted off from Cape Canaveral and successfully deployed Explorer I. Von Braun was not in the blockhouse at Cape Canaveral. Instead, he had travelled to Washington, D.C. to be with Pickering and van Allen for a press conference on what they hoped would be a successful mission. But in a letter to his father two days later, the Marshall Center Director expressed his remorse at not being at the launch saying, “When one has worked for 28 years on such a thing and now expects the culmination, it was a fairly bitter pill.”1

One hundred and eight minutes after launch, JPL’s Frank Goddard confirmed Explorer I’s successful orbit saying, “We’ve got the bird.” At 2:00am, von Braun, Pickering, and van Allen attended the press conference and photo event at the National Academy of Science. The next morning, the headline in the Huntsville Times read, “Jupiter-C Puts Up Moon.”

Explorer I relayed information from space to Earth stations until May 23, 1958, when its batteries were exhausted. It continued to orbit for several years before finally reentering the Earth’s atmosphere on March 31,1970.

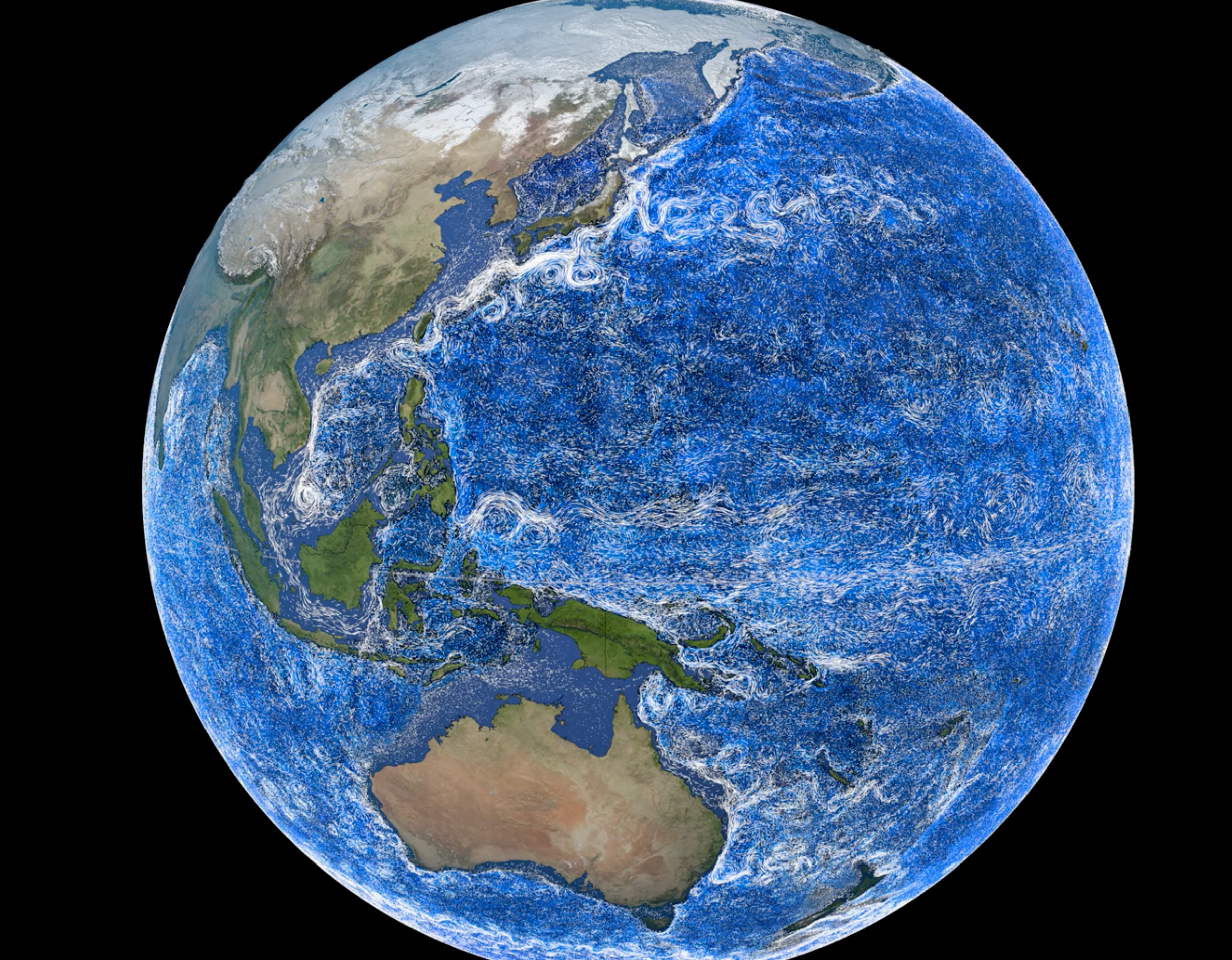

It is easy to forget the rationale behind the launching of orbiting satellites. Explorer I and Sputnik were both part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), an international effort at scientific cooperation that by the end of 1958 included 67 countries. Dr. Van Allen’s instrument, a simple cosmic ray detector, designed to measure the radiation environment in Earth orbit, initiated the discovery of the surrounding belts of charged particles held in place by the Earth’s magnetic field, today known as the Van Allen radiation belts.

On the day the satellite disintegrated upon reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere, Dr. van Allen declared its success to be “one of the landmarks in the technical and scientific history of the human race.” The satellite had indeed “revealed the existence of radiation belts around the Earth and opened a massive new field of scientific exploration in space” and “inspired an entire generation of young men and women in the United States to higher achievement and propelled the Western World into the Space Age.”2

Today, NASA is developing the Space Launch System (SLS), a powerful, advanced launch vehicle that is to be the enabling technology for our national goal of deep space exploration. With its unprecedented power and capabilities, SLS will launch crews of up to four astronauts in the agency’s Orion spacecraft on missions to explore multiple, deep-space destinations. Standing on the foundations laid by Explorer I in the initial foray into space, SLS seeks to open a new era of deep space exploration and scientific discovery.

Footnotes

[1] Quoted in Mike Neufeld, Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War, New York: Knopf, 2007.

[2] Quoted in “Explorer’s Legacy” at the University of Iowa Library, http://explorer.lib.uiowa.edu/

Bibliography

Bille, Matthew A. and Erika Lishock. The First Space Race: Launching the World’s First Satellites. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004.

Dickson, Paul. Sputnik: The Launch of the Space Race. Toronto: MacFarlane Walter & Ross, 2001.

Foerstner, Abigail. James Van Allen: The First Eight Billion Miles. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2007.

Green, Constance M. and Milton Lomask. Vanguard: A History. Washington, D.C.: NASA Historical Series, 1970.

McDonald, Frank and John E. Naugle. “Discovering Earth’s Radiation Belts: Remembering Explorer 1 and 3.” EOS Vol. 39:23 (23 September 2008) 361-376.

Mieczkowski, Yanek. Eisenhower’s Sputnik Moment: The Race for Space and World Prestige. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Mudgway, Douglas J. William H. Pickering, America’s Deep Space Pioneer. Washington, D.C.: NASA Historical Series, 2008.

Neufeld, Michael J. Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War. New York: Knopf, 2007.