By Linda Herridge

NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center

(with NASA Historical Mission Information)

Fifty years ago this month, NASA’s Apollo 13 mission would have been the agency’s third Moon landing and lunar exploration mission. A movie and several books relate the story of this challenging mission which has been described as a “successful failure.”

Apollo 13 started long before launch, with final processing, testing and verification of the command and service module (CSM) and the lunar module (LM) in the high bay of what was then called the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (now the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. This process had been performed for all of the previous Apollo missions.

“The Apollo command and service module, called Odyssey, and lunar module, called Aquarius, each arrived as two pieces, and we stacked them together,” said Bob Sieck, former NASA project engineer for the Apollo spacecraft. “The O&C was a busy place. It was home to us.”

The mated CSM and LM were transported to the Vehicle Assembly Building, where they were integrated with the Saturn V rocket. The Apollo 13 stack rolled out to Launch Pad 39A on March 24, 1970.

Sieck said processing of the hardware was normal with no major hiccups. The team did know that one of the liquid oxygen tanks on the service module had a potential issue as the result of a handling incident in California.

A Countdown Demonstration Test was conducted at the pad, which included loading of cryogenic propellants, resulting in the occurrence of a significant event that was different from all other previous flow tests. The test team was unable to offload the CSM fuel cell liquid oxygen from tank #2 after completion of the test.

“We contacted the subject matter experts at Johnson Space Center, who were available 24/7 even when there wasn’t a mission, and government and contractor subject matter experts from around the country and other NASA centers,” Sieck said. “They advised us to use the tank’s heaters to boil off the liquid oxygen. We did and it worked.”

John Tribe was the North American-Rockwell (NAR) manager for the Apollo CSM propulsion systems. “I was in the Automatic Checkout Equipment Station in the O&C during the offloading test, and I remember the consternation, discussions and telecons that ensued as the team struggled to offload the liquid oxygen tank.”

While using the heaters to boil off the liquid oxygen, the temperature gauge in the oxygen tank could not track temperatures above 80 degrees. The tank’s pressure remained normal. But, Sieck said unknown to the team, the temperature inside the tank reached 1,000 degrees Farenheit and melted some of the insulation on the wiring.

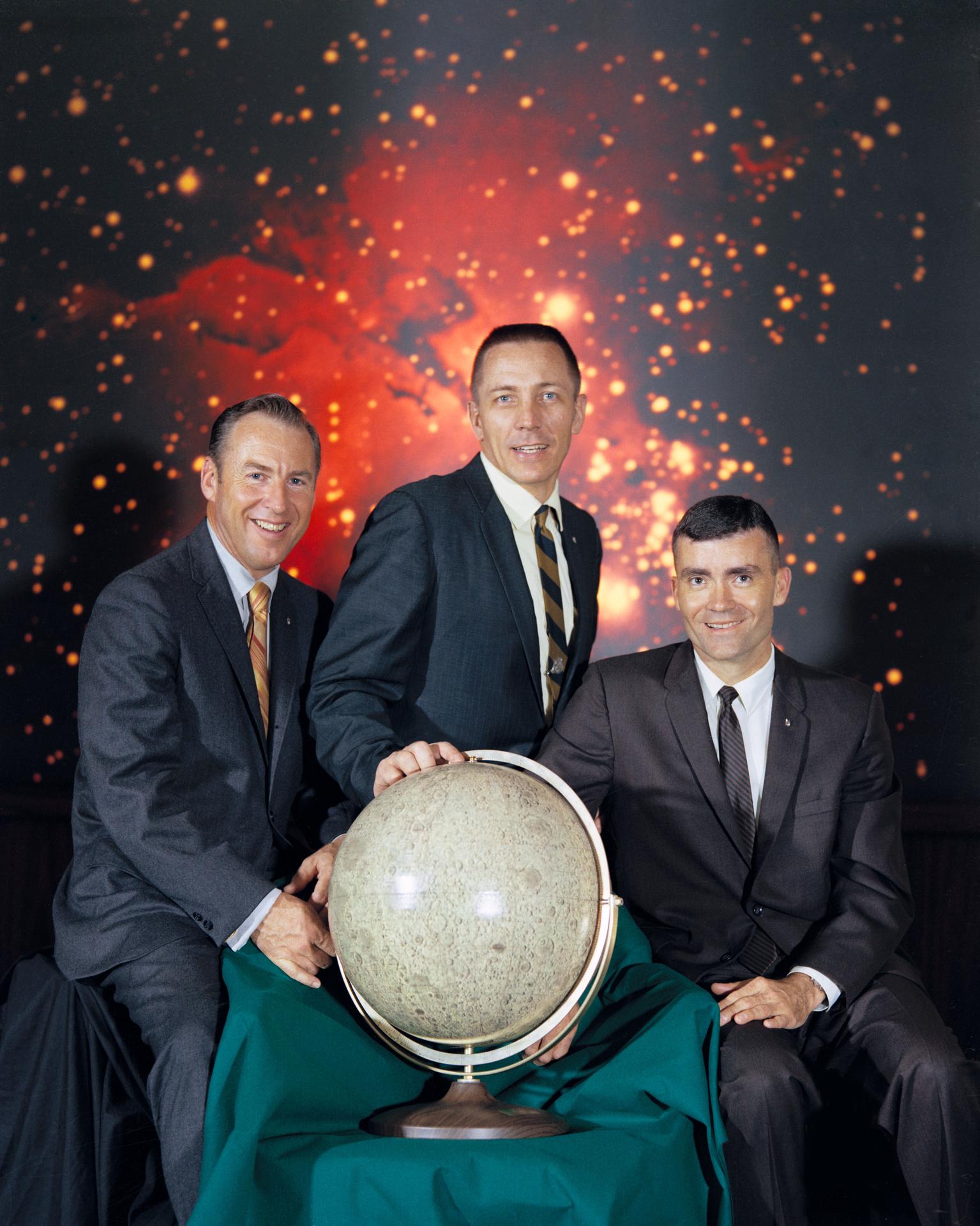

On April 11, 1970, the Saturn V rocket (designated SA-508) lifted off from Launch Pad 39A at Kennedy, carrying Apollo 13. Launch was at 2:13 p.m. EST. Inside the command module were James A. Lovell Jr., commander; John “Jack” Swigert Jr., command module pilot; and Fred W. Haise Jr., lunar module pilot. Of the three, only Lovell had flown in space.

Selected as an astronaut in 1962, Lovell was making his fourth spaceflight and second trip to the Moon, the first person ever to achieve these milestones. He served as pilot of Gemini VII in December 1965, command pilot of Gemini XII in November 1966, and command module pilot of Apollo 8 in December 1968, the first piloted mission to the Moon.

Both Haise and Swigert were selected as astronauts in 1966. Swigert served as a member of the astronaut support crew for the Apollo 7 mission and backup crew for Apollo 13, until called upon to join the crew for this mission. After his spaceflight, Haise was called upon to serve as commander for the Shuttle Approach and Landing Tests conducted in 1977.

Nearly three minutes after launch, the first stage engines shut down, it separated from the second stage, and fell back to Earth, where it impacted the Atlantic Ocean. The second stage ignited, but the center engine shut down a little earlier than planned due to some vibrations in the propulsion/structural system. This early shutdown caused considerable deviations from the planned trajectory. The remaining second stage engines burned 34 seconds longer than planned, then shut down and separated.

The Saturn IVB, also called the third stage, ignited at nearly 10 minutes into flight and then burned 9 seconds longer than planned, placing the Apollo CSM into orbital insertion. The crew and launch team verified the vehicle and spacecraft systems were ready to leave Earth orbit and head to the Moon about 1.5 hours into flight. The second maneuver occurred about 2.5 hours into flight. The crew performed transposition and docking with the lunar module, then the CSM and LM separated from the S-IVB stage. Unlike previous missions, where the third stage passed by the Moon and went into a solar orbit, this third stage impacted the Moon so that vibrations resulting from the impact could be sensed by the Apollo 12 seismic station on the lunar surface and telemetered to Earth for study.

During the first 46 hours of the mission, as the spacecraft was about a third of the way to the Moon, the crew observed that oxygen tank 2 was performing normally. They routinely turned on the fans, and in about three seconds, the tank’s quantity indicator read “off the scale” at more than 100 percent. Another request to cycle the oxygen tanks was performed by the crew. Telemetry from the spacecraft was lost almost totally for 1.8 seconds. During that loss, the caution and warning system alerted the crew to a low voltage condition. At that time, the crew heard a loud bang and realized there were problems.

“It went in various sequence,” said Jim Lovell, during an oral history project interview in May 1999. “The light came on. Something was wrong with the electrical system. We eventually lost two fuel cells. We couldn’t get them back. Then we saw our oxygen being depleted. One tank was completely gone. The other tank had started to go down. Then I looked out the window, and we saw gas escaping from the rear end of the spacecraft.”

Lovell said it was Jack Swigert who said it first: “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”

“At the time of the explosion, I was in the lunar module,” said Fred Haise during an oral history project interview in March 1999. “I knew it was really happening, and I knew it was not normal, and serious just at that instant. I did not know that it was life-threatening.”

An array of warning lights came on. Haise said looking over the instrument panel it became very clear in short order that the pressure meter, the temperature, and the quantity meter needles for one of the oxygen tanks was down in the bottom of their gauges. “It effectively told me we had lost one oxygen tank,” Haise said.

What began as a mission to land on the Moon, became a mission to survive and return safely to Earth.

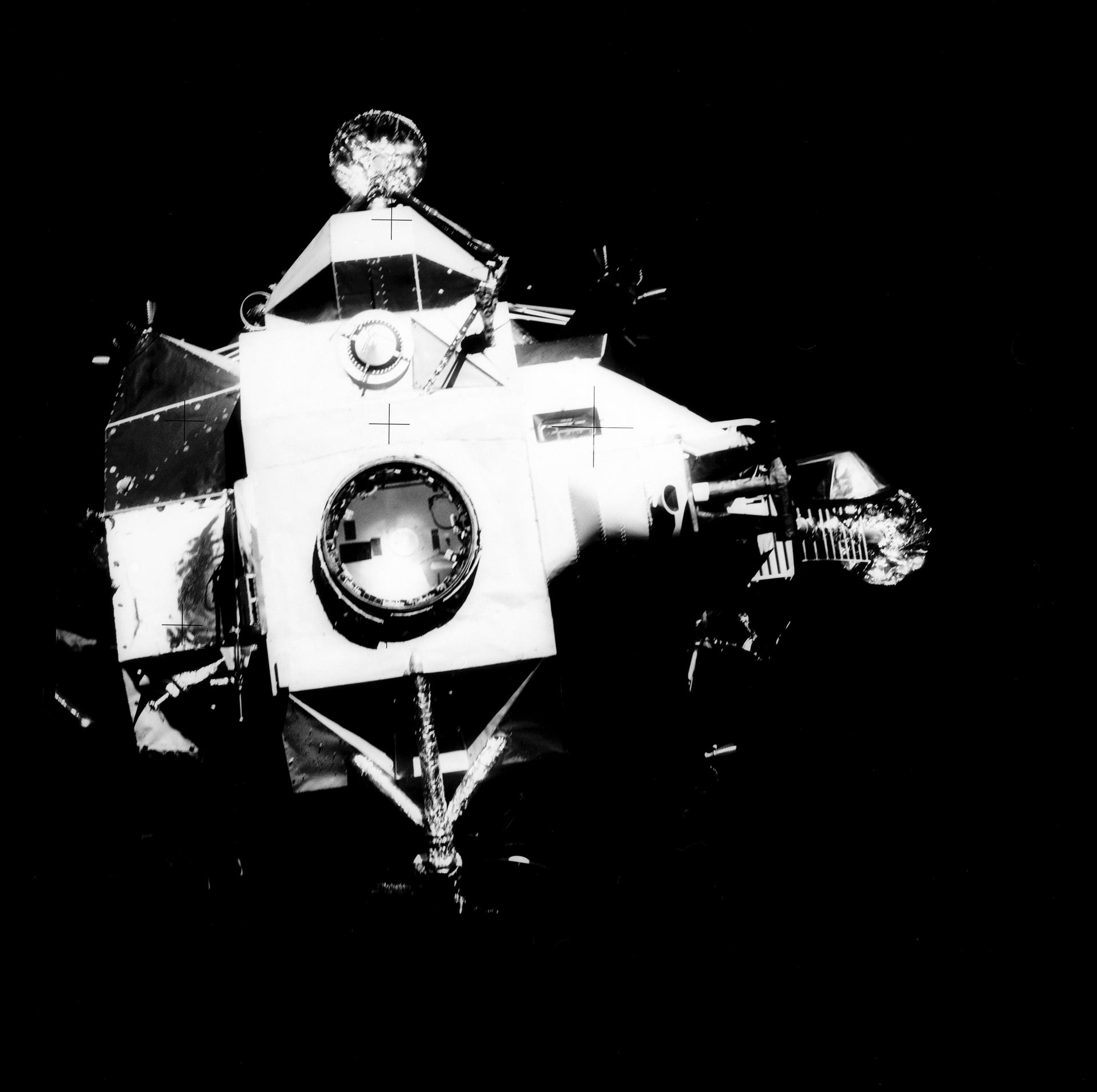

Realizing the implications of the damaged oxygen tank, the crew quickly went to work shutting down the fuel cells and power on the command module and transferring into and powering up the lunar module, a “lifeboat,” where they remained for the duration of the mission as they waited for the plan to return home.

Mission Control at Johnson Space Center decided the best course of action was for the crew to slingshot around the Moon and use it for a free return trajectory back to Earth. During the remainder of the mission, the crew completed two main activities: planning and conducting the necessary propulsion maneuvers to return the spacecraft to Earth, and managing the use of consumables so the LM would support three crew members and serve as the actual control vehicle for the time required.

The most critical consumables were water, used to cool the CSM and LM; battery power needed for use during re-entry; the LM batteries needed for the rest of the mission; oxygen for breathing; and lithium hydroxide filter canisters to remove carbon dioxide from the spacecraft cabin atmosphere.

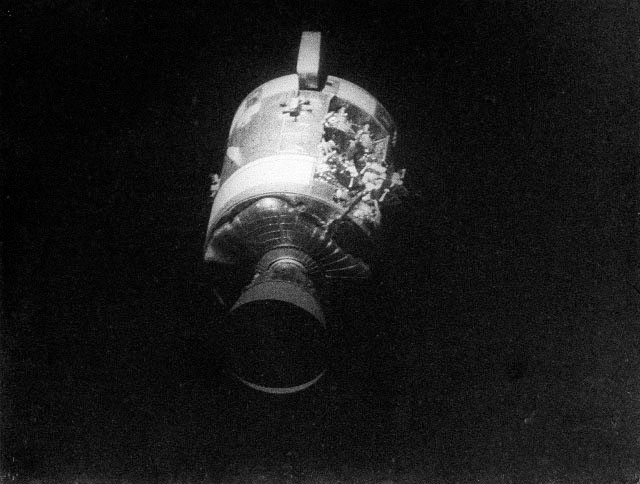

After firing the LM descent engine, the CSM looped behind the Moon and was out of contact for 24 minutes and 35 seconds. At about 138 hours into the mission, the crew jettisoned the service module from the command module. “When we jettisoned the service module and it floated by, we saw this big, gaping hole, this panel blown out. That worried us that our heatshield was damaged, because it was right next to our heatshield,” Lovell said.

The lunar module was retained until about 70 minutes before entry into Earth atmosphere. A few pieces of the LM survived entry and they struck the open sea between Samoa and New Zealand. The CM re-entered Earth’s atmosphere at about 142 hours into the mission, at a velocity of 36,210 feet per second.

The command module splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on April 17, 1970, at 1:07 p.m. EST. The crew was retrieved by helicopter and transported to the recovery ship, the USS Iwo Jima. Total flight time for Apollo 13 was 5 days, 22 hours, 54 minutes and 41 seconds.

“My favorite memory from this mission was watching the crew hop out of the helicopter and onto the ship after being retrieved from the ocean,” Sieck said. “I call the mission Lucky 13, because if the crew had started up the lunar module and headed on a path to the Moon, which would have used up their consumables needed to return to Earth, the ending may have been different.”

After the in-flight tank failure, Tribe was directed by his company to head up their Kennedy investigation team supporting the formal NASA investigation. “I worked some of the longest hours in my career, coordinating with NAR in Downey, California, Houston, the fuel cell and tank manufacturers at Pratt and Whitney and Beech Aircraft. We helped to establish the trail of events and errors that caused the explosion,” Tribe said. “Corrective actions were taken over the next nine months to preclude such an event occurring in the remaining Apollo flights.”

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 13 mission, NASA is now bringing that historic flight effectively back to the future through the agency’s Apollo Challenger Columbia Lessons Learned Program (ACCLLP). The ACCLLP, through numerous innovative methods, shares the lessons learned from Apollo 13 with a wide array of agencies, industries, companies and academic institutions across the world.

“Apollo 13’s iconic mission will forever be enshrined into our collective history. However, through ACCLLP, the lessons learned from the accomplishments of the crew and ground teams that brought them home, now have an essential role to play in successfully returning America back to the Moon and on to Mars,” said Mike Ciannilli, ACCLLP Program manager. “We are reaching a new generation of space explorers.”