The excerpts below are taken from Discovery Program oral history interviews conducted in 2009 by Dr. Susan Niebur and tell the story of the hurdles the MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) mission team faced with the technical requirements of visiting Mercury, budget challenges, and schedule impacts —all while keeping their mission goals in mind on the way to launch.

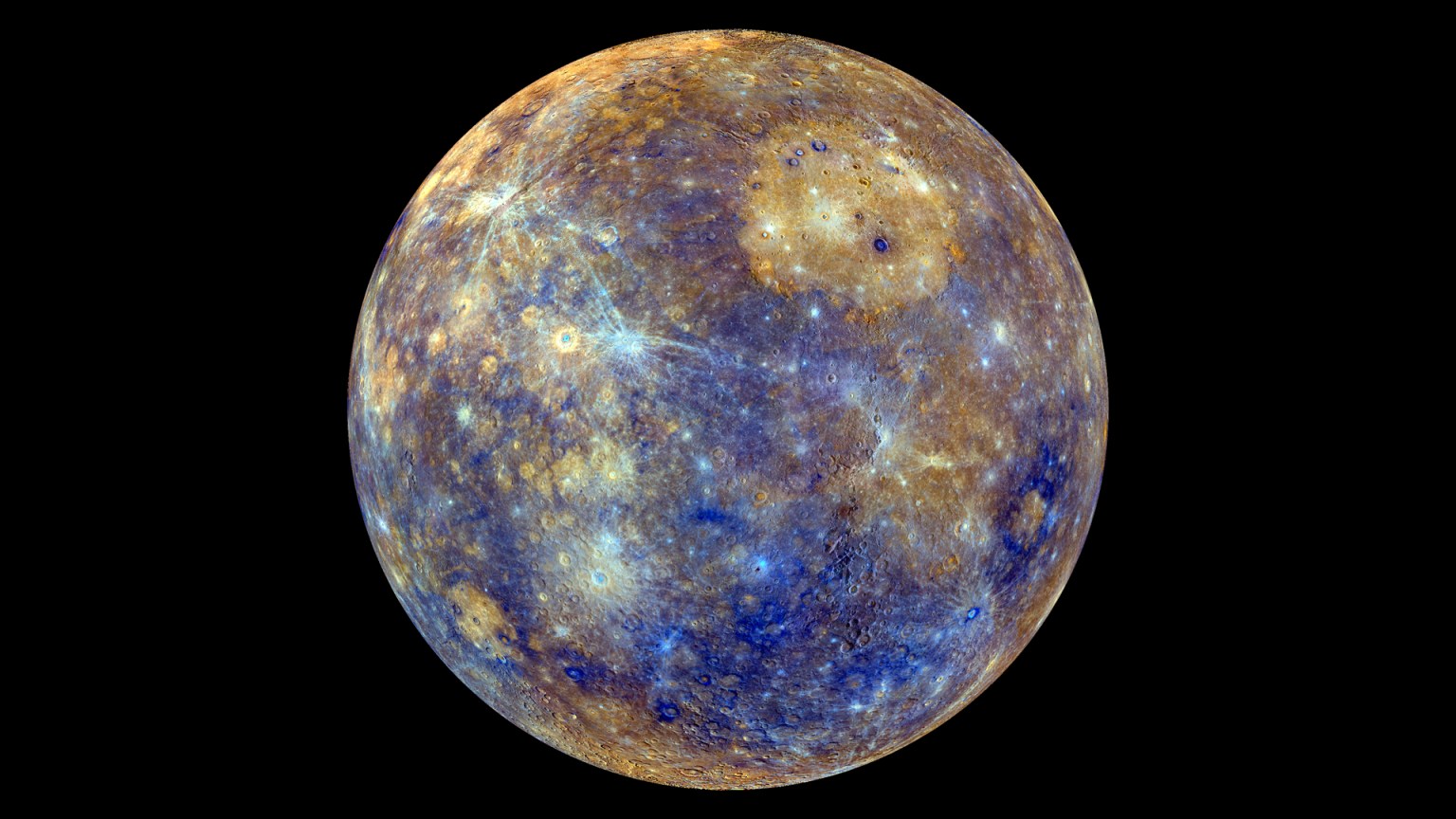

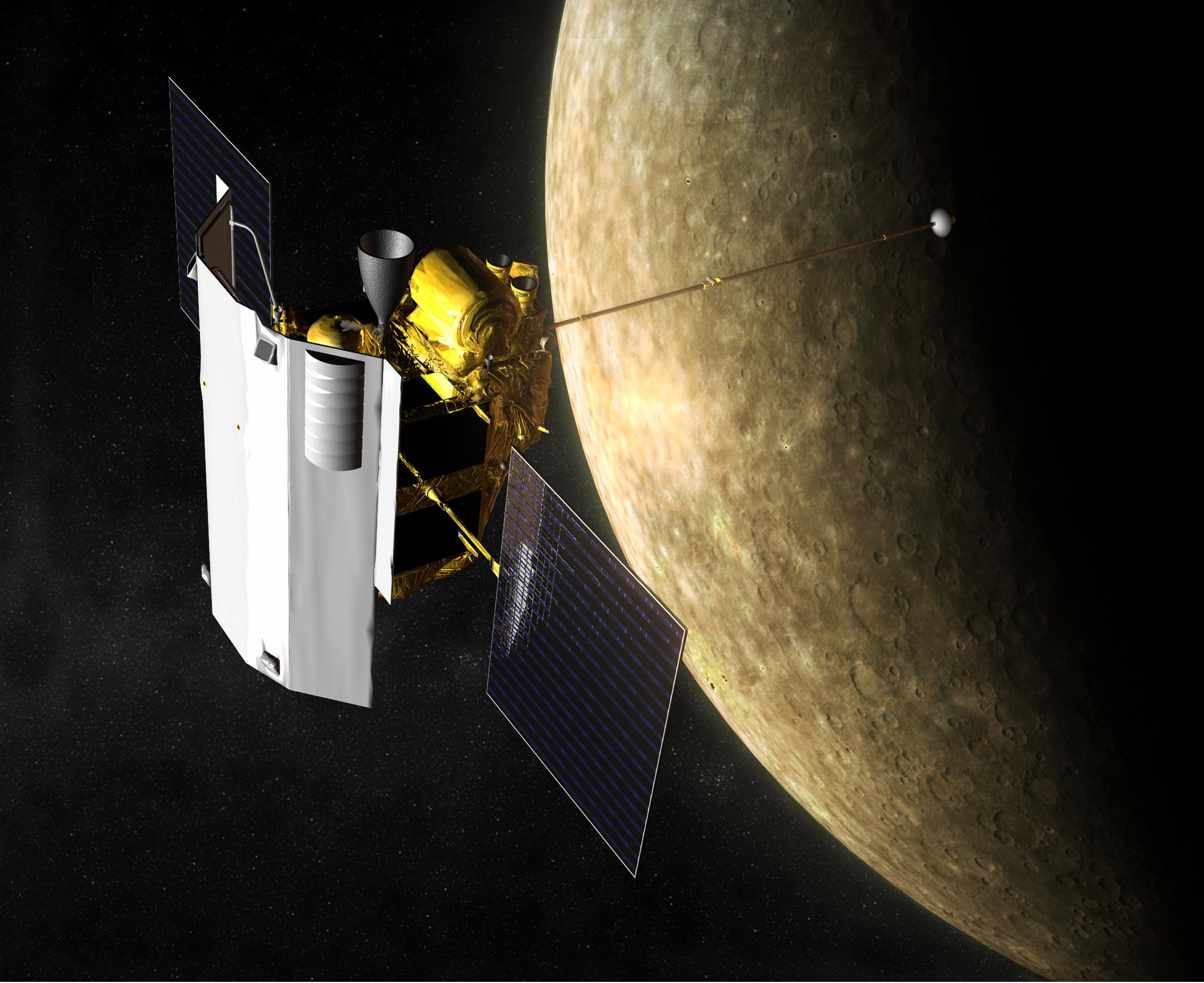

The MESSENGER mission followed a long road from conception to launch with multiple detours and obstacles along the way. First conceived by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) after NASA’s 1996 Discovery Program Announcement of Opportunity, the mission to Mercury proposal, if accepted, would be the first spacecraft to visit the planet since Mariner 10’s flybys in 1974. A critical step for APL was finding the right principal investigator (PI) to lead the mission.

"These projects are so huge"

Andrew F. Cheng, MESSENGER Co-Investigator

“There’s not that many people out there, especially in the early days when the PI [principal investigator-led] mission paradigm itself was just getting set up. You didn’t want to screw up. You didn’t want to have a problem. …Scientific qualifications are necessary, but that’s not even the biggest part of it. It’s knowing something about missions and seeing how they work with engineers and also how they handle Headquarters and how they handle the program management. It’s a whole variety of things.

“Number one is the cachet to help you win the mission. And then there’s the consideration, ‘Okay, what if we win and we’re actually stuck with this guy? All right, he better be able to work with the engineers, better know how to listen, better realize that, yes, you’re in charge, but you’re not really.’ PIs don’t know everything and they have to know how to delegate. These projects are so huge…they can’t get their fingers into everything.”

"This sounded like fun"

Sean Solomon, MESSENGER Principal Investigator

“APL decided that they thought they could do a Mercury orbiter mission. They were doing NEAR [Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous] at the time. They had ambitions to do more things in solar system exploration.

“I got a call from John Appleby, who was the head of development for the APL space department at the time. He said, ‘We are looking to put together a team of scientists for a Discovery proposal, a Mercury orbiter. Would you be interested?’

“I said sure. …This sounded like fun. I hadn’t given a great deal of thought to Mercury for almost 20 years, then. This is spring of 1996. But it was something I had wanted to do for 20 years. It was a chance. …The next thing I knew I got a call from Tom Krimigis, …and he said, “Can you come out to APL?” I had never been to APL. So I drove out there and I was late because I didn’t know how bad the beltway traffic would be. I came into this room with 10 people waiting for me, and the gist of it was, they asked me, ‘Would you like to be PI? You already said you would be on the science team for the mission, how about being PI?’…

“I was naïve in a lot of ways. I didn’t appreciate all of the aspects of the things I would have to know. For instance, when we wrote that first proposal. The first time we wrote it, it got accepted [and moved] to the second round [of competition]. I put a lot of effort into the science rationale, which was the first 25 pages of the proposal. But I had to accept that the engineering team really knew what they were doing. I wasn’t in a position to critically evaluate the confidence with which they had solutions to particular technical challenges. I didn’t know that much then about risk management. I didn’t know how to ask all of the questions that I learned how to ask about. Nor did I know how to evaluate project managers, the first time around.

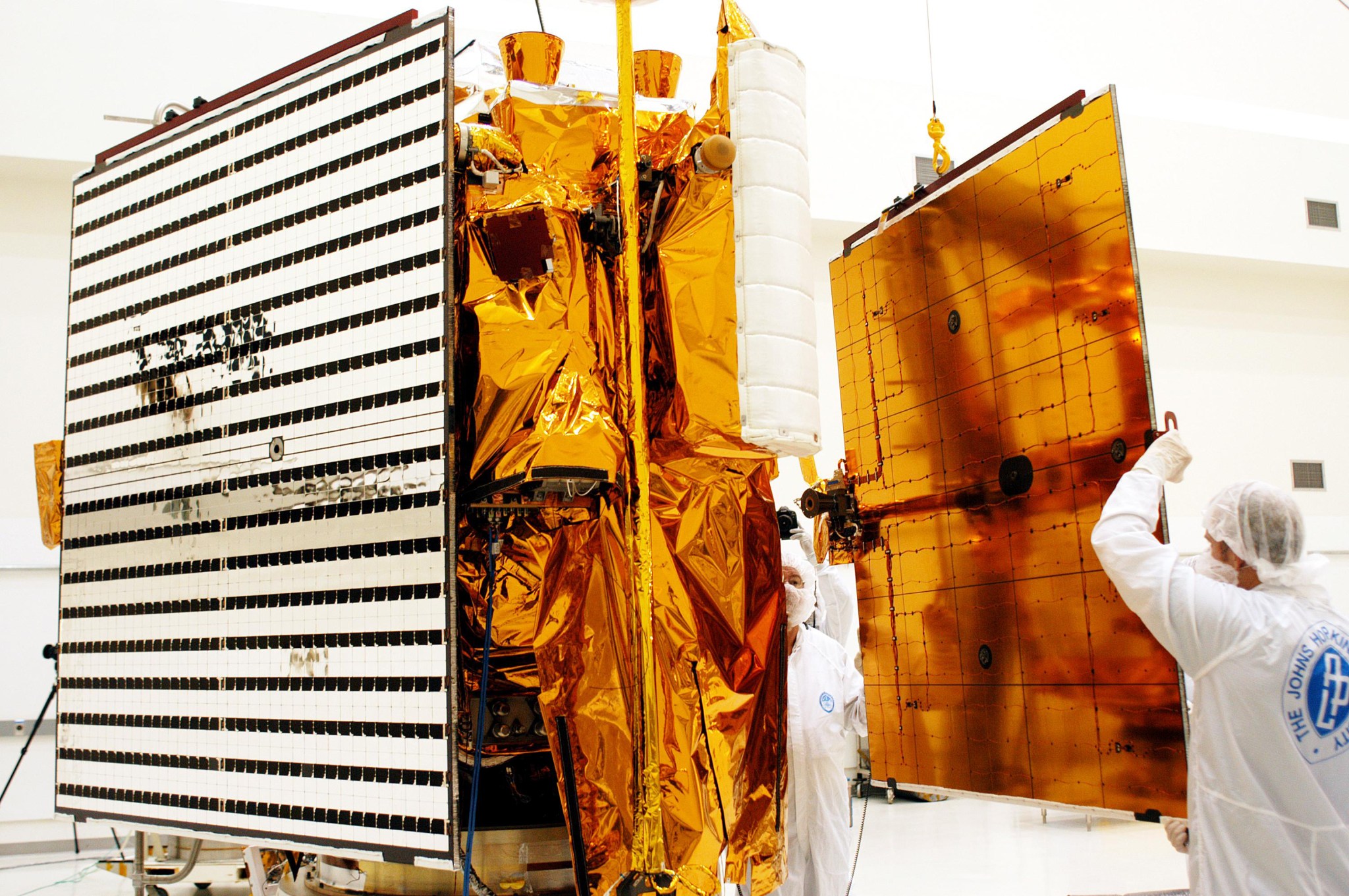

“At the time of our site visit [a requirement during the second round], we had a development path for the solar arrays, which was worked out, but in the questions and answers it was clear we didn’t have a sufficient contingency plan. If any of the testing proved that our assumptions were not appropriate…we didn’t have a deep plan for what to do next. And so we were really sharply dinged on the solar arrays, which have to face the Sun. We hadn’t done enough testing to be absolutely confident to the level of being able to persuade a legitimately skeptical review panel that we had the right solution.

“The other place we got hammered was that the budget did not come together. This was the project manager’s fault. It didn’t come together in a way that could be shared with the team, including the PI, before the site visit. The budget was so late that he didn’t put all the numbers together until the night before the presentation, and some of that information that had gone out to the site review team didn’t add up. …And there was nobody there who could help him because nobody had seen it. It had been put together so last minute….I wasn’t sufficiently skeptical in the areas where I was ignorant. So I certainly bear a lot of responsibility [for not being chosen].”

After that first disappointment, the MESSENGER team regrouped and proposed again in 1998 after some changes to the team and after addressing significant problems that were identified in the first proposal. The second proposal was accepted for development on July 7, 1999.

"Somebody who knew about risk"

Sean Solomon, MESSENGER Principal Investigator

“We had a meeting and agreed that we would re-propose. I said I want a new project manager…we had to have a rapport, someone who could work well with his own engineers. Somebody whose budgets I believed. Somebody who knew about risk. Somebody who had had some experience. They said, ‘We think we have somebody for you. We would like you to meet Max Peterson.’ Max and I hit it off. So he became the proposal manager and the project manager for the second proposal.

“We had to solve the solar array problem. And APL did that by doing the testing. They developed a testing protocol. They put the resources in. They figured out how to do the test at NASA Glenn [Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio]. So by the time we wrote our second proposal, and particularly by the time of the second site study, we could say, ‘Not only do we have a solution for the solar arrays, here are all the tests that validate our models.’

“So, the first time we proposed we were low risk in round one and high risk after the site visit, high risk being the solar arrays and not having a good project manager. But we were low risk both times the second time through.”

Two separate Mars missions lost their spacecraft to failures in 1999 — the Mars Climate Orbiter in September and the Mars Polar Lander in December. As a result, NASA set up the NASA Integrated Action Team [NIAT] to study these failures and make recommendations going forward for all small missions, including the Discovery missions. For the newly selected MESSENGER mission, this imposed a significant effect on the planned budget and timeline because of the added mandates for risk avoidance.

"Reviews upon reviews upon reviews"

Tom Krimigis, APL Space Department head

“Well, needless to say, we felt sort of punished, even though we were innocent. Some of that also was very disappointing because we did have several of these reviews, and they pointed out certain things that needed to be done. But they were imposed on the system, and at the same time not paid for, and also not relaxing the schedule in any way, because we had a specific deadline to launch and so on. So, these were mandates. And that’s part of the problem with the reviews upon reviews upon reviews, that there is no incentive for the review teams to somehow be mindful of the schedule and the cost.

“I complained to Headquarters at one time that we had a third of the staff acting on the recommendations from the previous review; another third preparing for the next review; and the final third was actually doing work. I mean, it was really horrendous.”

"Keep marching forward"

Ralph McNutt, MESSENGER Project Scientist

“I think what did happen was then the NIAT report came out, and it was like we were told, ‘Well, things are going to happen differently.’

“And of course, we were in the middle of trying to get this thing pulled together when all of this was going on. Quite frankly, I think looking back on it, it’s not that we didn’t take it seriously, it’s just that if you’re going to keep your budget down, you’ve got a certain number of people. And unfortunately there are only 24 hours in the day and occasionally it’s probably good to sleep during some of those.

“So we had [asked for] an original amount of money, which we got, which was, looking back on it, way too small considering what was going to be coming down the pike at us. And as all of this started coming together about what the implications really were. ‘Wait a minute. We’re not going to make it.’ And we got into a bit more hardball with some of the powers that be at that point.

“We didn’t get nearly all of what we’d asked for. And we said, ‘Well, we’re not going to give up. We’re going to keep marching forward.’ And we did have to go back and ask for more money. Sean ended up giving presentations to four of the different NASA advisory subcommittees down at NASA Headquarters.

“All the committees agreed that it should go forward. There were some other people down at NASA Headquarters that weren’t very happy with that assessment. …I think everybody was frustrated. It wasn’t like we felt like we were coming up roses. …I don’t know that it was so much a feeling of vindication as the feeling that we had managed to evade the executioner’s blade.”

As the mission development continued, delivery delays from subcontractors presented another schedule and cost impact. And the cost reviews at NASA Headquarters were causing more worry for the team.

"Not a standard review"

David Grant, MESSENGER Project Manager

“My first meeting was called a Risk Retirement Review. It was covered by an independent assessment team that had been following the program for some time. I went to the review and I began to sense that there were some serious problems going on in the program. The review was not a standard review. It was requested by Colleen Hartman, and I believe her title at the time was Director for the Division of Planetary Science.

“And so we get into the details and it was clear from the start that there was a very big struggle to try to keep the program cost under the [budget] cap. It was a very big concern about that.

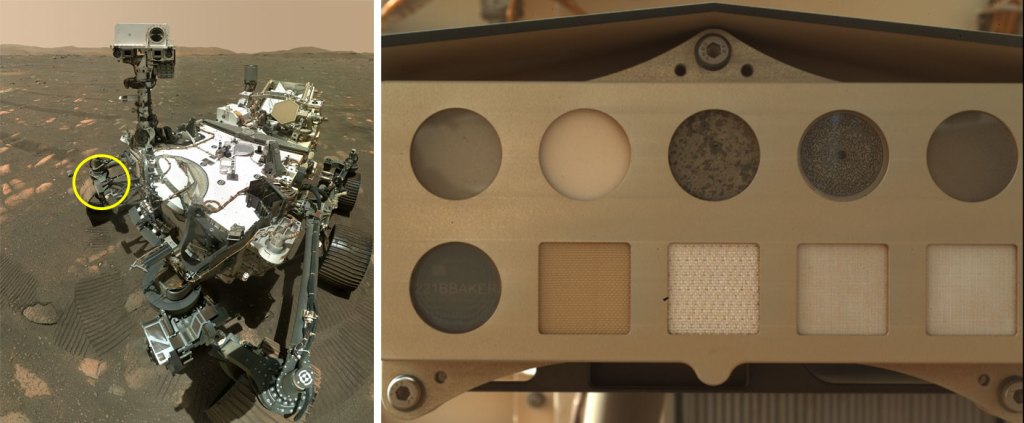

“There were problems. We had problems with the IMU [Inertial Measurement Unit]. It was very late and Northrup Grumman was having a heck of a time with it. Also, just as I came in the door, they had announced that one of the solar array substrates had cracked in testing. What were they going to do about that $100,000 rebuild? We had an autonomy system to protect the spacecraft that was stuck. It was a very comprehensive system, trying to do everything. Everywhere I looked there were cost and schedule problems.

“Now you have to understand, MESSENGER is a very tough mission. You have to keep your eye on the spacecraft weight, on the propulsion, and on the thermal. An awful lot of technology. The guys that were working the job were very good people, but it was a very tough job. So, I really wasn’t surprised to see that there were problems. I mean this is a program with an awful lot of technology development. An awful lot. And we were having problems. So, we had the review and came out of it with some recommendations. But it was clear to me, very clear, that we had blown the cost cap. This was something that my own management did not want to hear, but there was no way that we could complete the work and stay under the program cap.”

The delays and cost mounted, but the team still worked toward their March 2004 launch date. The stress of the situation affected work schedules and team morale, and the mission leadership had to find ways to keep people motivated and moving forward.

"We wanted to get to Mercury sooner"

Sean Solomon, MESSENGER Principal Investigator

“We were projecting delays at that point in key subsystem deliveries that came to pass. One of the most painful was the spacecraft structure. That was subcontracted to an outfit called Composite Optics in California, because APL had never done a structure made out of composites. But we did it to keep the dry mass of the spacecraft down. Composite Optics is a fine company, but they’re a small company, and the mission that they had to finish before us was MER [Mars Exploration Rover]. MER was four months late on the delivery of their spacecraft, the bus that flew the MER to Mars. And there was nothing we could do.

“So that set our integration and test schedule four months in arrears from the beginning. Because the spacecraft structure had to go to the propulsion system guys, who integrated it. And then those guys delivered an integrated propulsion system and structure to APL. So that put us deeper in the hole.

“But there were other things going on at the time. We were really sweating the inertial measurement unit. There was a company that built these things outside of Santa Barbara in Goleta, California. They were bought by Northrup Grumman. And Northrup Grumman decided to close the Goleta plant, and they tried to get people who knew how to do this to move down to Woodland Hills. Well, nobody who lives in Santa Barbara wants to live in LA. So none of them moved. So they had to reproduce the expertise to build these very complicated gyros. All new people.

“They missed every deadline…. But there were other technical issues, and they were all eating away at our schedule. Still, we were working toward a schedule that would have had us go in our first launch window, which was March of 2004. There was another window in May of 2004. There was a third, less desirable window in August of 2004. So we had three windows, by good fortune, in 2004.

“We particularly didn’t want to have the August launch, because that was the energetically least favorable launch. The March and May launches involved cruise times of 5 years. The August launch, which is the one we eventually used, was a 6 ½-year cruise. And so not only would we get to the planet much later, but there would be a big Phase E cost increase. So we didn’t want to go there. We wanted to get to Mercury sooner. So, in the winter of 2003 we were still aiming for the March 2004 launch. ”

"Things kept coming up"

David Grant, MESSENGER Project Manager

“You need to have the subsystems delivered in a certain order. Well, first of all, many were being delivered late. We were shooting for a March launch. So, we made the subsystems move their delivery dates in. That took more money to get that done.

“For electrical integration and test, I had an 18-person team working double shifts, sometimes triple shift, sometimes seven days a week. There’s an impact. The thing you have to be careful about is burn out…. But we get through that summer. Now we were on schedule for launch in March of 2004.

“Well, things kept coming up. …So, around that time I met with Tom Krimigis and department management and I just told them that in my view we were not going to make the March launch date. I thought that the schedule reserve that we had was insufficient for where we were in the program. Still had nine months to go, more or less, and we didn’t have enough schedule reserve. It was diminishing, and, in my view, I thought we should notify our sponsor that we were going to recommend a schedule slip.

“So, we said, move the launch out to May of ’04. Well, there was a cost associated with that. It’s a couple more months of development time. It’ll also impact down at the Cape [Canaveral, Florida]. They were getting ready for the March launch. Now it’s May. Okay, the launch day was going to be different but they have to keep the team together and that affects everything.

“We got into the final stages of development. We completed integration and test and then the environmental tests over at Goddard and we had our pre-ship review here and everybody in creation was at it. We went through the pre-ship review and we go by the numbers. I present, the system engineer presents, the subsystem people present, autonomy people got up and spoke and said we’ve completed testing. We’re very confident of where we are, we’re good to go, and ready to launch in May 2004.

Now you could have cut the tension with a knife in the room — very high tension

David G. Grant

MESSENGER Project Manager

“Now you could have cut the tension with a knife in the room – very high tension. So, the reviewers had a private room they all went into and voted. They came out and they say, ‘Okay, Dave, we’re going to ship.’ So we got the team going and they packed the whole thing up, and we shipped it all to the Cape.

“But something was wrong. Management was not at ease. We were not at ease…. Not everybody was comfortable and I could sense that.

“We shipped it and then the first weekend it was there and I got a call Sunday night from Mike Griffin [the new head of the APL Space Department] and he says that NASA was concerned about autonomy. ‘Well, there’s concern that we haven’t done enough testing of the autonomy system. They want you to do more testing in several areas.’

“I said, ‘Well if NASA wants us to do the testing, we’ll do the testing. But they have to understand the consequences.’ If we go from May to August there’s a development cost…. We have an Earth flyby, two Venus flybys and three Mercury flybys before we get into orbit. Also, five major propulsive burns. That’s a lot more difficult trajectory than the May launch was. It’s a much higher risk trajectory. Also, the cost impact could be as much as $30 million.

“In addition, the margins on the spacecraft, the power margin, the thermal margin, were much tighter with this new mission. So, I said, ‘NASA has to recognize that the risk is from launch to orbit. And you have to take everything into account. So you can keep that spacecraft here and do another few weeks of testing and go with Flight 2, or you can go with Flight 1 as approved at the pre-ship review. NASA’s got to decide if the additional testing is worth it. It’s a much higher risk mission at a much higher cost. But if NASA wants to do it, we’ll salute and we’ll do it.’ So Mike said, ‘It’s non-negotiable.’ “

The launch window in August 2004 finally arrived, but the Florida weather made the long road a little more perilous. On the second launch attempt, August 3, 2004, MESSENGER began it’s long journey to Mercury.

"Everything was go"

Sean Solomon, MESSENGER Principal Investigator

“We launched on the second day of an almost 3-week window. Vestiges of a tropical storm had stopped us the day before. The day didn’t satisfy the constraints on clouds, but we came very close. We came within a few minutes of liftoff. We were out there at night, watching. And then the next night everything was go. Which was good, because another storm came through a day or two later that turned into a hurricane.”

After a successful launch, the team had to do come catching up on mission and science planning because of the delays in launch and the effect of those delays on the mission itself.

"An excellent spacecraft"

David Grant, MESSENGER Project Manager

“So right after we launched, we had to do the whole mission planning all over again, analysis that we had done before launch. Ordinarily you’d have it all packaged up good to go. All the science planning had to be done again. All the mission design had to be done again. And. in the meantime, we had to learn how to fly the spacecraft, which involves a level of trial and error.

“Initially, the spacecraft was difficult to operate. We didn’t know where the center of the gravity was. So when we did little thruster burns, for trajectory correction, there were errors, and they were significant enough that they had to be corrected. We had to learn how to deal with that. We had plume impingement—that wasn’t anticipated prior to launch. We had to deal with that. And in the meantime, there are literally thousands of different parameters onboard. Were they all right? No, there were a few that needed adjustment. Some were approximations.

“The first time we tried something, it didn’t work exactly the way we had hoped it would, so we had to go back and correct it. Each of these events were characterized as anomalies; they had to be corrected. And we spent a lot of time doing that. The shakedown cruise for MESSENGER was much more difficult than I thought it was going to be.

“Well, a lot of new technology, and the first time out flying. It’s like anything complex and new. But the engineering team stayed with it. They ran every problem to ground. They understood the reasons for the anomaly and fixed it. They were very thorough and diligent. And finally, one day, we all realized all the problems were pretty much fixed and that MESSENGER was an excellent spacecraft.”

/quantum_physics_bose_einstein_condensate.jpg?w=1024)