A native of Emaus, Pennsylvania, Margaret W. ‘Hap’ Brennecke was the first female welding engineer to work in the Materials and Processes Laboratory at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. A true trailblazer in the field of aluminum alloys – a skill set critical to the success of the Apollo program – Brennecke spent her long career building large structures and breaking barriers in a previously male-dominated field.

Following completion of a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the Ohio State University in 1934, Brennecke conducted graduate work in metallurgy at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the University of Pittsburgh, and the University of California in Los Angeles. Brennecke spent the following 22 years as a research metallurgist with the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) Process Development Laboratory investigating new processes for using aluminum in large structures and developing new alloys. Over these years, Brennecke also embraced a love of travel spending time in Russia in 1958 and taking trips aboard freighters travelling to and from bauxite mines on the Caribbean island of Trinidad.

It was World War II that provided Brennecke with the opportunity to move from chemistry to the field of welding and alloy fabrication. During the war, Brennecke worked to determine alloys and joining methods for aircraft, railroad equipment, bridges, pontoons, and landing craft like those used during the 1944 Normandy invasion. Along with many other women in the era, Brennecke seized upon the opportunities offered by the rapidly expanding wartime economy and a shrinking male labor force which was fighting in Europe and the Pacific theaters. Discrimination on the basis of her gender followed Brennecke throughout her career. Brennecke noted that her nickname, “Hap,” allowed her to disguise her gender in written reports and correspondence beyond the laboratory.

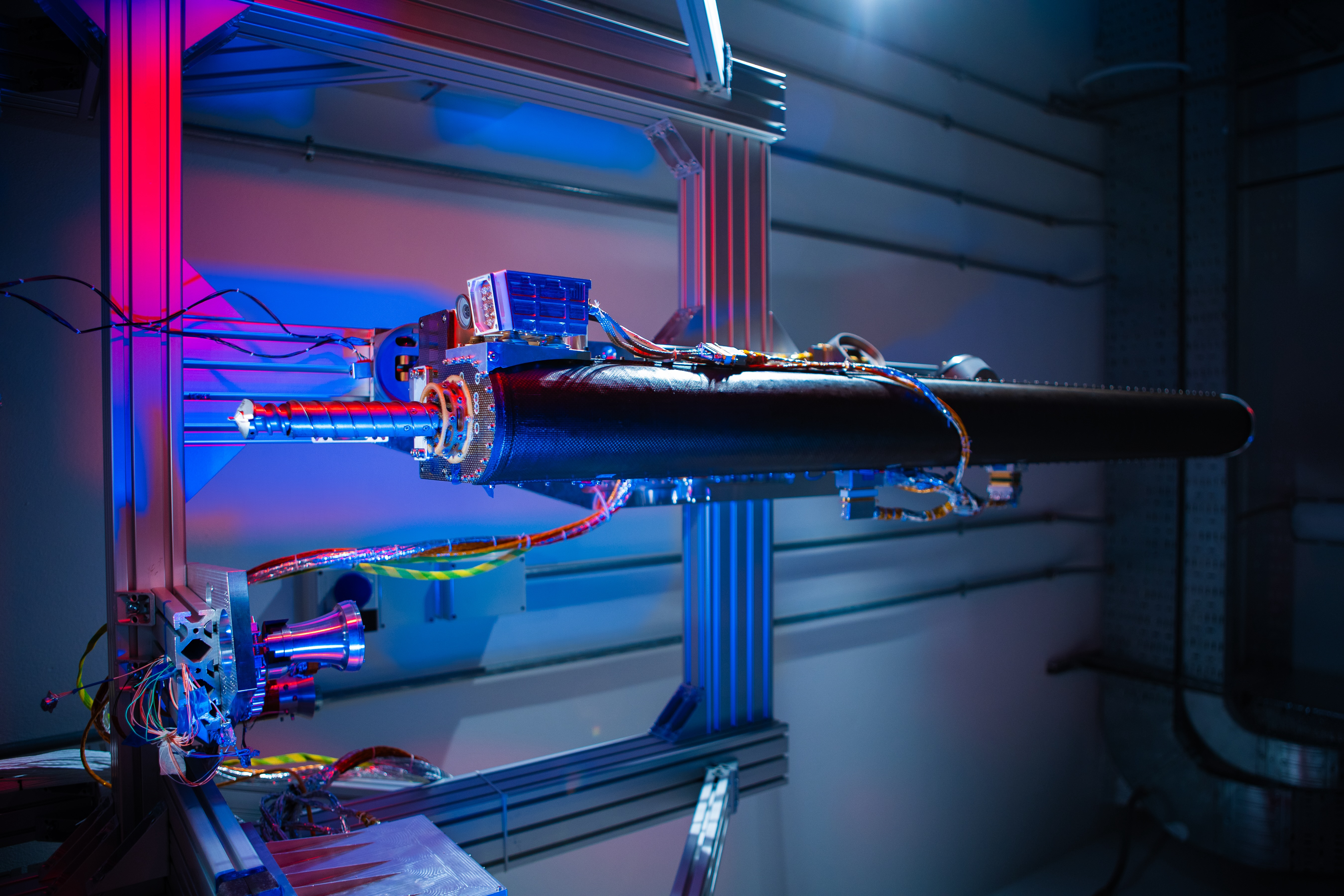

In 1961, Brennecke joined the Marshall Space Flight Center in a position of welding expert, bringing with her a vast knowledge of aluminum alloys and TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) and MIG (Metal Inert Gas) welding processes. Throughout the Saturn era, Brennecke was called upon by center management to make critical decisions on the selection of lightweight high-strength metals and welding techniques for the huge Saturn stages. Specifically, Brennecke provided metallurgical engineering support for solving the problems of obtaining the required heat treatments, cold work, and metallographic structure leading to high strength and reliability in thick aluminum welds of cryogenic fuel tanks. She also contributed to the important research efforts leading to optimal thermal-aging treatments for those high-strength aluminum alloys.

Brennecke published several articles during this period – one entitled, “Electron Beam Welding of 2219 Aluminum” in the January 1965 issue of Welding Journal and a NASA Technical Report on the “Evaluation of 2021 Aluminum Thermal Treatments” in May 1968. Brennecke held memberships in the American Society of Metals, American Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, American Welding Society, and the Society of Aerospace and Materials Process Engineering. She was also a fellow in the Association for the Advancement of Science. Brennecke also held a 1957 Canadian patent for the aluminum alloy 7277.

Following the Saturn program, Brennecke was assigned to the Metallic Materials Division of the Center’s Materials and Processes Laboratory where she worked on metallic material and process selection and evaluation for Spacelab hardware and the solid rocket boosters for the Space Shuttle Program. Brennecke brought her immense experience to the selection of high strength steels, both in terms of data from experienced users to information on primary and secondary forming capabilities across the country. In 1974, Brennecke was a member of the committee responsible for rewriting the Military Handbook 5, the Metallic Materials and Elements for Aerospace Vehicle Structures – the most authoritative source for aerospace metals and alloys data.

Throughout her career, Brennecke fielded many cliched questions regarding women in the workplace. As part of an interview with the Marshall Star in 1962, Brennecke was asked “How does a woman invade a so-called man’s world?” Brennecke’s answer continues to ring true in the twenty-first century – “Establish yourself on the basis of what you can contribute, not of the basis of being a gal.”