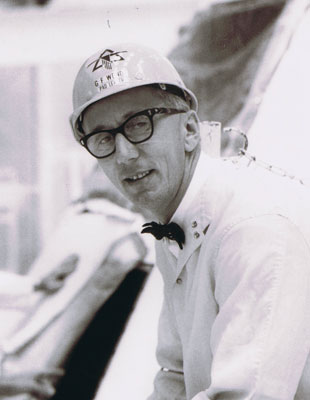

Guenter Wendt

May 3, 2010 (Courtesy NASA) Guenter Wendt, the legendary pad

leader who

often was the last person astronauts saw before going into space, died

at his home Monday morning in Merritt Island, Fla., within a few miles

of NASA's Kennedy Space Center. Wendt had been hospitalized with

congestive heart failure and suffered a stroke. He was 85.

He worked at Kennedy for 34 years.

Wendt, a naturalized American originally from Germany, spoke with a thick accent and made a reputation as a strict overseer of the launch pads and of the spacecraft the astronauts flew. Those traits earned him the nickname "Pad Fuhrer." He also was the first pad leader for crewed spacecraft.

The movie "Apollo 13" made famous the line about the pad leader when Tom Hanks, as astronaut Jim Lovell, asked, "I wonder where Guenter Wendt?"

Fact was, Wendt was never far from the space program. He stood watch over the Mercury and Gemini missions. The contractor for the Apollo spacecraft did not retain him as a full pad leader, Wendt recorded in his memoirs. So, Wendt was at home when the Apollo 1 fire erupted and killed Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee as they ran through a countdown test at Launch Pad 34.

Afterward, astronauts including Wally Schirra insisted on Wendt's return. Wendt was in charge of the White Room and launch pad when Schirra and his crew lifted off on Apollo 7, the first crewed Apollo mission after the fire. Wendt saw all the Apollo astronauts off on their way to the moon, too, before working as the head of flight crew safety for the Space Shuttle Program. He later served on the investigation board that reviewed the Challenger accident.

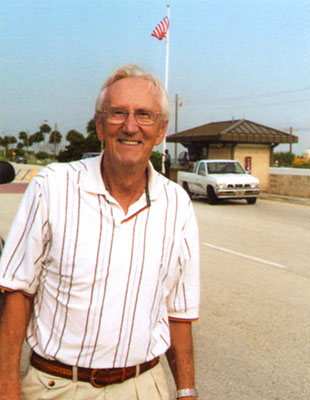

He retired in 1989, but still didn't leave the space program far behind. He worked as a consultant on Hanks' production "From the Earth to the Moon," and also worked with the team that recovered the Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. That was the Mercury capsule Gus Grissom flew into space, but the spacecraft filled with water after splashdown and sunk.

He also returned to Kennedy on occasion and spoke with today's spaceflight engineers, technicians and specialists.

In May 2009, Wendt told them to establish credibility, learn from mistakes and "think outside the box." He also told them, "Don't fake it. Always have the facts to back up your statements," and "never take things for granted."

Wendt is survived by three daughters.

He worked at Kennedy for 34 years.

Wendt, a naturalized American originally from Germany, spoke with a thick accent and made a reputation as a strict overseer of the launch pads and of the spacecraft the astronauts flew. Those traits earned him the nickname "Pad Fuhrer." He also was the first pad leader for crewed spacecraft.

The movie "Apollo 13" made famous the line about the pad leader when Tom Hanks, as astronaut Jim Lovell, asked, "I wonder where Guenter Wendt?"

Fact was, Wendt was never far from the space program. He stood watch over the Mercury and Gemini missions. The contractor for the Apollo spacecraft did not retain him as a full pad leader, Wendt recorded in his memoirs. So, Wendt was at home when the Apollo 1 fire erupted and killed Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee as they ran through a countdown test at Launch Pad 34.

Afterward, astronauts including Wally Schirra insisted on Wendt's return. Wendt was in charge of the White Room and launch pad when Schirra and his crew lifted off on Apollo 7, the first crewed Apollo mission after the fire. Wendt saw all the Apollo astronauts off on their way to the moon, too, before working as the head of flight crew safety for the Space Shuttle Program. He later served on the investigation board that reviewed the Challenger accident.

He retired in 1989, but still didn't leave the space program far behind. He worked as a consultant on Hanks' production "From the Earth to the Moon," and also worked with the team that recovered the Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. That was the Mercury capsule Gus Grissom flew into space, but the spacecraft filled with water after splashdown and sunk.

He also returned to Kennedy on occasion and spoke with today's spaceflight engineers, technicians and specialists.

In May 2009, Wendt told them to establish credibility, learn from mistakes and "think outside the box." He also told them, "Don't fake it. Always have the facts to back up your statements," and "never take things for granted."

Wendt is survived by three daughters.

Guenter Wendt, 85,

'Pad Leader' for NASA's moon missions, dies

May 3, 2010 — Guenter Wendt, the original pad leader

for NASA's manned space program who was the last man the Apollo

astronauts saw before launching to the moon, died at his home in

Merritt Island, Fla., early Monday morning after being hospitalized for

congestive heart failure and then suffering a stroke. He was 85.

Reporting to Cape Canaveral as a McDonnell Aircraft Corp engineer working on missile projects soon after gaining his American citizenship in 1955, Wendt, who was born and educated in Berlin, became part of the effort to launch the first U.S. astronauts into space. As pad leader -- or "pad führer" as the astronauts came to affectionately call him due to his strong German accent and unwavering rules -- Wendt oversaw the spacecraft on the launch pads and all who had access to them to ensure the safety of all those involved. Read more about Wendt in this 2002 interview: A Vital Link: Guenter Wendt and the meaning of responsibility As he recalled in "The Unbroken Chain," Wendt's memoirs released in 2001, "If you came up to the spacecraft, you didn't touch it without my permission. During emergencies, I wouldn't have time to form a committee. I had to make sure I had the authority to make the decision whenever anything became critical." "Simply put, in an emergency the buck stopped with me," Wendt shared with his co-author Russell Still. But when a fire broke out in the Apollo 1 spacecraft on the pad, an emergency that ultimately claimed the life of three astronauts, Wendt was not there. After serving as the pad leader for the Mercury and Gemini missions, a change in contractors resulted in Wendt being reassigned. "I showed them my previous job description," Wendt wrote about North American Aviation, "and explained my need to have complete control in the white room." "They simply could not give that type of authority to a new comer [to the company]," Wendt described, adding that he was offered a "watered-down version" of the position, but had to decline. So it was by television that Wendt learned of the fire on the pad on Jan. 27, 1967. "I remember the sudden weight I felt in my shoulders," he described in his book. "I slumped down in my chair as if I weighed a thousand pounds." "It seemed the blackest moment of my entire life and I cried at their loss," Wendt revealed. After the accident, NASA, and in particular Apollo 1 back- up astronaut Wally Schirra who was to command the next mission, demanded North American hire Wendt and give him full control of the white room and spacecraft. Wendt's first task was to identify the changes and develop the emergency procedures for the flight crew and his team on the pad, so that such an emergency would not happen again.  It was his commitment to their safety that earned Wendt the respect of the astronauts. "Guenter was always a welcome sight in the white room," wrote the late Gordon Cooper, one of the first seven U.S. astronauts and the last to fly a solo Mercury mission. "He was the very essence of integrity and reliability and gave us a terrific boost in confidence on every launch." But even the spacemen were under Wendt's rule when in and around the spacecraft. "It's easy to get along with Guenter," shared Pete Conrad. "All you have to do is agree with him." Wendt was more than the astronauts' launch pad manager though, he was also their friend and a familiar face to see them off. Though he didn't close the hatch to the spacecraft himself ("that was my technicians"), Wendt was always the last to lean in and make sure the moon-bound crews were ready to go. "I [would] lean in and ask each astronaut, 'Are you happy with your straps, with everything?' Everybody says 'Okay,' we shake hands, 'Good luck, guys,'" Wendt said in a 2002 interview. Wendt and the astronaut crews exchanged more than just pleasantries on the pad, they also traded gifts -- and not just any gifts, but gag gifts. Looking to relieve some of the pressure off the astronauts during what was a highly stressful time, Wendt presented them with handmade 'gotchas' and they answered in kind. "Thinking of the ceremonial 'key to the city' that frequently was given by politicians to visiting dignitaries, I came up with the idea of a key to the moon," Wendt related in his book about the styrofoam crescent moon he fashioned for Neil Armstrong. "Armstrong gave me a small card that was stuck under the wristband of his Omega watch. It was a ticket for a space taxi ride, good 'between any two planets.'" Wendt never had the chance to redeem the ticket and ride into space himself, although he continued to oversee the safety of the astronauts through the end of the Apollo program and beginning flights of the space shuttle. He retired from the space program in 1989, after serving on the accident review board convened at Kennedy Space Center to investigate the loss of Challenger.  Even after his departure, Wendt remained active in space activities. In addition to authoring "The Unbroken Chain," he served as a technical consultant for Tom Hanks' HBO miniseries "From the Earth to the Moon," even making a cameo appearance. Wendt was also recruited for the raising and recovery of the only U.S. manned spacecraft to be lost at sea, Liberty Bell 7, the Mercury spacecraft flown by Gus Grissom. He was there when the capsule was lifted off the ocean floor. "Let me just go ahead and touch it after 38 years," Wendt said, as the spacecraft he helped launch sat before him in 1999. Most recently, Wendt traveled just last month for the 40th anniversary of Apollo 13, taking part in a panel discussion hosted by the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center in Hutchinson. One of the white rooms in which Wendt spent his time preparing spacecraft is exhibited at the museum. Wendt is survived by three daughters. |