Chapter 15

Return to Flight: Richard H. Truly

and the Recovery from the

Challenger Accident1

by John A. Logsdon

Seventy-three seconds after its 11:37 a.m. liftoff on September 29,

1988, those watching the launch of the Space Shuttle Discovery and

its five-man crew breathed a collective sigh of relief. Discovery

had passed the point in its mission at which, on January 28, 1986, thirty-two

months earlier, Challenger had exploded, killing its seven-person

crew and bringing the U.S. civilian space program to an abrupt halt.2

After almost three years without a launch of the Space Shuttle,3

the United States had returned to flight.

Presiding over the return-to-flight effort for all but one of those

thirty-two months was Rear Admiral Richard H. Truly, United States Navy.

Truly was named Associate Administrator for Space Flight of the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on February 20, 1986. In that

position, he was responsible not only for overseeing the process of returning

the Space Shuttle to flight, but also for broader policy issues such as

whether the Challenger would be replaced by a new orbiter, what

role the shuttle would play in launching future commercial and national

security payloads, and what mixture of expendable and shuttle launches

NASA would use to launch its own missions. He served as the link between

the many entities external to NASA the White House, Congress, external

advisory panels, the aerospace industry, the media, and the general public

with conflicting interests in the shuttle's return to flight. In addition,

he had the tasks of restructuring the way NASA managed the Space Shuttle

program and restoring the badly shaken morale of the NASA-industry shuttle

team.

The citation on the 1988 Collier Trophy presented to Admiral Richard

H. Truly read: "for outstanding leadership in the direction of the recovery

of the nation's manned space program." This essay recounts the managerial

and technological challenges of the retum-to-flight effort, with particular

attention to Richard Truly's role in it. However, as Truly himself

1. This essay's findings and conclusions are the responsibility of

the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of NASA or the George

Washington University. The author wishes to acknowledge with gratitude

the dogged research assistance of Nathan Rich; without his efforts, the

task would have been much more difficult.

2. This essay is not an account of the Challenger accident,

but rather the process of recovering from that mishap. For such an account,

see Malcolm McConnell, Challenger: A Major Malfunction (Garden City,

NY: Doubleday, 1987).

3. The formal name for the combined Shuttle orbiter, Space Shuttle

main engines, external tank, and solid rocket boosters, plus any additional

Spacelab equipment mounted in the orbiter's payload bay, is the Space Transportation

System(STS). In this essay, the terms Shuttle or Space Shuttle

are often used as an alternate way of identifying the STS.

345

346 RETURN TO FLIGHT

|

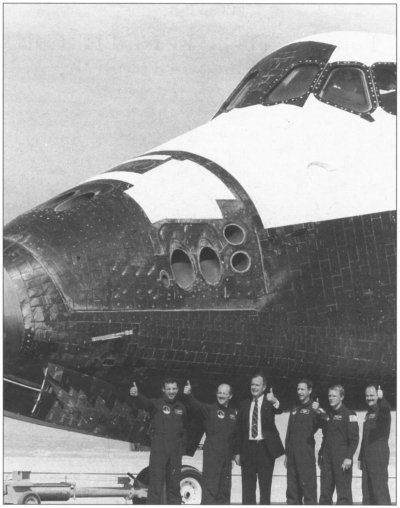

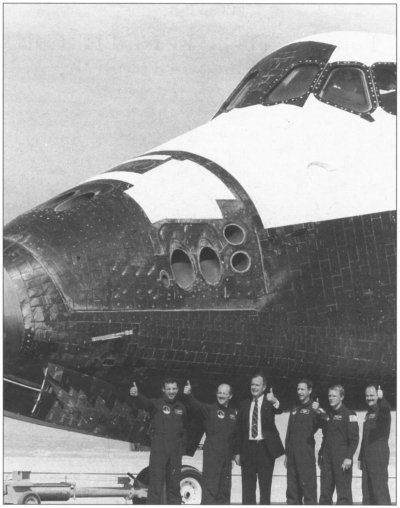

| It's thumbs up for the shuttle as the STS-26 Discovery

crew celebrate their return to Earth with Vice President George Bush. The

orbiter completed a successful four-day mission with a perfect touch down

on October 3, 1988, on Rogers Dry Lake Runway 17. In this picture, from

left to right, are: Mission Specialist David C. Hilmers, Commander Frederick

H. (Rick) Hauck, Vice President George Bush, Pilot Richard O. Covey, and

Mission Specialists George D. Nelson and John M. Lounge. (NASA photo no.

88-H-497). |

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 347

recognized, the recovery program was a comprehensive team effort;4

as the first post-Challenger flight approached, he sent a memorandum

to the "NASA Space Shuttle Team," saying:

As I reflect over the challenges presented to us, and our

responses to them, my overriding emotion is one of pride in association.

You the men and women who compose and support this unique organization

should take great pride in having renewed the foundation for a stronger,

safer American space program. I am proud to have been a part of this effort;

I am proud to have witnessed your extraordinary accomplishments.5

Immediate Post-Accident Events6

When Truly was named NASA Associate Administrator for Space Flight,

he told the press that in the three weeks since the Challenger accident

he had not "had one moment" to review information about the mishap.7

Whether he realized it or not, Truly was entering a very chaotic situation.

At the time of the accident, NASA Administrator James Beggs was on a leave

of absence to deal with a Federal indictment unrelated to his NASA duties.

(Beggs was later completely exonerated of any wrong doing and even received

a letter of apology from the Attorney General for being mistakenly indicted.)

Acting as Administrator was NASA Deputy Administrator William Graham, a

physicist with close ties to conservative White House staff members but

no experience in civilian space matters prior to being proposed for the

NASA job. A few weeks earlier, Graham had been named Deputy Administrator,

a White House political appointment, over the objections of Beggs and other

senior staff at NASA; in his short time on the job he had remained largely

isolated from career NASA employees. When Challenger exploded, NASA was

thus bereft of experienced and trusted leadership.

Graham was in Washington when the accident occurred. Later in the day,

be flew to the Kennedy Space Center with Vice President George Bush and

Senators John Glenn and Jake Garn. The latter three flew back to Washington

after consoling the families of Challenger crew members and meeting

with the Shuttle launch team. Graham stayed behind; in a series of phone

calls to the White House during the night, a decision was made to have

the President appoint an external review commission to oversee the accident

investigation. Although Graham had been briefed by his NASA staff on how

the investigation after the 1967 Apollo 1 fire had been handled,

he apparently did not argue that the NASA Mishap Investigation Board, set

up immediately after the accident, should continue to lead the inquiry.

This naming of an external review panel was in marked contrast to what

had happened nineteen years earlier, on January 27, 1967. When he learned

that a fire during a launch pad test had killed the three Apollo 1

astronauts, NASA Administrator James Webb immediately notified President

Lyndon Johnson, and told him that NASA was best qualified to conduct the

accident investigation. Webb later that evening told his associates that

4. Of those who worked closely with him in the return-to-flight effort,

Truly singles out for particular praise Arnold Aldrich, Richard Kohrs,

and Gerald Smith. Each of them, he notes "deserve an arm or a leg of the

Collier Trophy." Personal communication to the author, August 14, 1995.

5. NASA, Memorandum from M/Associate Administrator for Space Flight

to NASA's Space Shuttle Team, "Return to Flight," June 10, 1988.

6. Unless otherwise cited, this narrative of the return-to-flight effort

is based on accounts in the leading trade journal Aviation Week &

Space Technology (hereafter AW&ST), New York Times,

and the Washington Post. All three gave detailed coverage to the

effort.

7. New York Times, February 21, 1986, p. A12.

348 RETURN TO FLIGHT

"this is an event that we have to control .... We will conduct the investigation.

We will get answers. There will be no holds barred. We'll issue a report

that can stand up to scrutiny by anybody." Meeting with the President the

next day, Webb told him "They're calling for investigations.... A lot of

people think it's a real issue for the future, and that you ought to have

a presidential commission to be clear of all influences." But, argued Webb,

"NASA is the best organization [to do the investigation]."8

Johnson concurred in Webb's approach; NASA had already selected the initial

members of the accident review panel, and they set to work immediately.

Certainly there were external reviews of the Apollo fire, particularly

by NASA's congressional oversight committees. However, their starting point

was the NASA-led investigation.

By not even attempting to retain control of the Challenger accident

inquiry at the start, NASA found itself subject to searching external scrutiny

and criticism, and the space agency had to share decision-making power

during the return-to-flight effort with a variety of external advisory

groups overseeing its actions. Dealing with, on one hand, the desire to

get the Shuttle back into operation as quickly as possible and, on the

other, the recommendations of advisory groups who gave overriding priority

to safety concerns and organizational restructuring, was one of Richard

Truly's greatest challenges between February 1986 and September 1988. This

was particularly the case as the accident investigation quickly changed

from one focused on the technical causes of the Challenger mishap

to one broadly concerned with NASA's organization and decision-making procedures.

On February 3, President Ronald Reagan announced that the investigation

would be carried out by a thirteen-person panel chaired by former Secretary

of State William P. Rogers; the group quickly became known as the Rogers

Commission. Reagan asked the Commission to "review the circumstances surrounding

the accident, determine the probable cause or causes, recommend corrective

action, and report back to me within 120 days."9

Within a few days after the accident, NASA investigators had pinpointed

a rupture in a field joint10 of the

shuttle's right Solid Rocket Motor(SRM) as the proximate cause of the Challenger

explosion. As the Rogers Commission began its work, there appeared to be

little controversy on this issue. However, in a closed meeting at the Kennedy

Space Center on February 14, Commission members were "visibly disturbed"

to learn that engineers from the firm that manufactured the SRM, Morton

Thiokol Inc., had the night before recommended against launching Challenger

in the cold temperatures predicted for the next morning; that their managers,

at the apparent urging of NASA officials from the Marshall Space Flight

Center, had overruled their recommendation; and that more senior NASA managers

responsible for the launch commit decision were unaware of this contentious

interaction. This was a "turning point" in the investigation; the Commission

immediately went into executive session. It decided that the NASA team

working with the Commission should not include any individual who had been

involved in the decision to launch Challenger. It decided to broaden

the scope of its investigation to include NASA's management practices,

Center-Headquarters relationships, and the chain of command for launch

decisions-in effect, shifting the focus of the inquiry from a technical

failure to NASA itself. At the end of its executive session, the Commission

issued a damning statement suggesting that NASA's "decision-making process

may have been flawed."11

8. Webb is quoted in W. Henry Lambright, Powering Apollo: James

E. Webb of NASA (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995),

pp. 144 and 146. Lambright provides an account of the Apollo fire investigation

on pp. 14288 of his book.

9. AW&ST, February 10, 1986, p. 24.

10. So-called because it was assembled at a NASA field center (Kennedy

Space Center) rather than at the manufacturer's plant.

11. AW&ST, February 24, 1986, pp. 22-25, and Boyce Rensberger,

"Shuttle Probe Shifted Course Early," Washington Post, March 17,1986,

pp. Al and A8. After a public hearing a week later in which much the same

testimony took place, William Rogers told the press that in his opinion

the decision-making process definitely "was flawed."

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 349

This indictment of shuttle management provided the backdrop against

which Richard Truly would work in succeeding months. As the Rogers Commission

tried to fix responsibility for the "flawed" decision to launch Challenger,

the agency was rampant with internal conflicts and finger-pointing. The

New York Times reported on its front page that the Marshall Space Flight

Center, the key organization for diagnosing and fixing the SRM problem,

was "seething with resentment, hostility, depression, and exhaustion."12Aviation

Week described the U.S. space program as being "in a crisis situation."13

Truly remarked in his first press conference "I have a lot to do"; he was

certainly not overstating the situation.

Truly Takes Charge

While he may have been unfamiliar with the details of the Challenger

mishap, Richard Truly was no stranger to the space agency; he had been

a NASA astronaut from 1969 to 1983, had piloted several of the early unpowered

tests of the shuttle, and had flown as pilot on the second shuttle mission

in November 1981 and as commander of the eighth shuttle mission in August-September

1983. He left NASA on October 1, 1983, to become the first head of the

Naval Space Command; it was from that position that he returned to NASA

to assume control of the Office of Space Flight. Truly was an engineering

graduate of the Georgia Institute of Technology and an experienced Naval

aviator. To most, the combination of his technical background and astronaut

experience and his absence from NASA for the period preceding the accident

made him well qualified to head the return-to-flight effort.

Truly spent his first weeks as Associate Administrator becoming familiar

with the situation he had inherited, organizing his immediate office, and

establishing a close working relationship with the Rogers Commission. As

soon as he entered office, Truly became chair of the "STS 51-L Data and

Design Analysis Task Force,"14 which

had been set up by Acting Administrator Graham to provide NASA support

to the Rogers Commission. One of Truly's crucial early decisions was to

bring in J. R. Thompson as vice-chair and day-to-day head of this task

force; in effect, this put Thompson in charge of NASAs part in the accident

investigation. Like Truly, Thompson had been a long-time NASA employee,

but had been in another job in the years preceding the Challenger mishap.15

Other members of the task force were astronaut Robert Crippen; Col. Nathan

Lindsay, Commander, Eastern Space and Missile Center; Joseph Kerwin, Director,

Space and Life Sciences, Johnson Space Center; Walter Williams, Special

Assistant to the NASA Administrator; and the leaders and deputies of the

six task force teams on development and production, pre-launch activities,

accident analysis, mission planning and operations, search, recovery and

reconstruction, and photo and television support that had been set up to

parallel the organization of the Rogers Commission investigation. The task

force in turn drew on all relevant resources of NASA.

Between intensive task force efforts during March and April 1986 and

the equally intense activities of the fifteen-person investigative staff

of the Rogers Commission (plus a parallel investigation by the staff of

the Committee on Science and Technology of the

12. New York Times, March 16, 1986, p. Al.

13. AW&ST, February 24,1986, p. 22.

14. The Challenger mission had been designated 51-L; as noted

above, STS was the acronym for the Space Transportation System, the official

name for the Space Shuttle.

15. Thompson had spent twenty years at the Marshall Space Flight Center

as an engineer and manager, but at the time of the accident had been for

three years the deputy director of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

in Princeton, New Jersey.

350 RETURN TO FLIGHT

House of Representatives),16 it

was unlikely that any aspect of the accident would go unexamined. This

was especially the case given the constant media scrutiny of the investigation.

By the end of March, Richard Truly was ready to go public with his return-to-flight

strategy. In a March 24 memorandum which he later described as a "turning

point" in the recovery effort,17 he

listed the "actions required prior to the next flight":

-

Reassess Entire Program Management Structure and Operation

-

Solid Rocket Motor (SRM) joint Redesign

-

Design Requirements Reverification

-

Complete CIL/OMI Review

-

Complete OMRSD Review

-

Launch/Abort Reassessment

Truly also spelled out the "orderly, conservative, safe" criteria for the

first post-accident Shuttle launch. These included: a daylight launch and

landing, a conservative flight profile and mission rules, conservative

criteria for acceptable weather, a NASA-only flight crew, engine thrust

within the experience base, and a landing at Edwards Air Force Base in

California. He closed the memo by noting that "our nation's future in space

is dependent on the individuals who must carry this strategy out safely

and successfully... It is they who must understand it, and they who must

do it."18

Truly reviewed his strategy before an audience of over 1,000 at the

Johnson Space Center; his remarks were televised to other NASA Centers.

He argued that "the business of flying in space is a bold business. We

cannot print enough money to make it totally risk-free. But we are certainly

going to correct any mistakes we may have made in the past, and we are

going to get it going again just as soon as we can under these guidelines."

The New York Times reported that "his upbeat words appeared to be meant

to lift spirits at the beleaguered agency and to turn the staff's eyes

forward to the shuttle's future. . . ."19

In just over a month after taking office, and well in advance of any

recommendations from the Rogers Commission and the Congress, Richard Truly

had set out the general outlines of the strategy he would follow over the

following two and one half years. However, that it would take that long

to return the Space Shuttle to flight was likely inconceivable to him and

his associates at the end of March 1986. NASA planning at the time called

for at worst an 18-month delay to July 1987 in launching the next shuttle.

Left to its own devices, it is possible that NASA and its industrial contractors

could have met this schedule. NASA was no longer a free agent, however;

the Challenger accident and the resulting external scrutiny of NASAs decisions

had changed the agency's freedom of

16. The report of the House investigation did not appear until October

and, with some differences in emphasis, basically reiterated the major

criticisms of the Rogers Commission. See House of Representatives, Committee

on Science and Technology, Investigation of the Challenger Accident,

House Report 99-1016, October 29,1986.

17. Personal communication from Richard Truly to author, August 14,

1995. In this communication, Truly noted that "in my view, the strategy

outlined in this memo (and in my JSC speech about it) was the turning point

in the recovery. Although I had taken great care to brief the strategy

to both Bill Graham and Bill Rogers, it significantly preceded any conclusions

of either the Rogers Commission or the Congress . . ., and therefore did

much to give NASA the leeway to implement it. Time and again, it was used

by me and others to keep the people, the program and the budgets on track;

in 1989, after the first year of successful flights were under our belt,

I went back and reviewed it carefully. Despite all that happened in the

interim, we had done almost precisely what was laid out in the March 24,

1986 memorandum."

18. Memorandum from M/Associate Administrator for Space Flight to Distribution,

"Strategy for Safely Returning the Space Shuttle to Flight Status," March

24, 1986. With respect to the acronyms used in Truly's memo: CIL=Critical

Items List; OMI=Operations and Maintenance Instructions; and OMRSD=Operational

Maintenance Requirements Specification Documents.

19. New York Times, March 26, 1986, p. D24.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 351

action forever. Over the coming months, Truly would have the almost

impossible task of balancing the pressure to fly as soon as possible in

order to get crucial national security and scientific payloads into space

while convincing the agency's watchdogs that a return to flight was adequately

safe. It was not to be an easy assignment.

Trying to Get Flying Soon

As mentioned earlier, it was clear within a few days of the accident

that the direct cause of the mishap had been a failure in the joint between

two segments of one of the shuttle's two solid rocket motors. That failure

was in turn quickly traced to the failure of the "O-rings" designed to

prevent the escape, through the joint, of the hot gasses generated during

SRM firing. On March 11, Acting NASA Administrator Graham told a congressional

committee that a redesign of the SRM joint and seals would be needed, and

estimated the cost of the redesign at $350 million.20

Responsibility within NASA for overseeing the SRM lay with the Marshall

Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. On March 25, Truly, acting

on his memorandum of the previous day, announced the creation of a Solid

Rocket Motor Team "to recommend and oversee the implementation of a plan

to requalify the solid rocket motor (SRM) for flight, including the generation

of design concepts, analysis of the design, planning of test programs and

analysis of results, and any other initiatives necessary to certify flight

readiness." The following day, Truly named James Kingsbury, Director of

Science and Engineering at Marshall, to head the team on an interim basis

.21

Within a few days, Kingsbury told The New York Times that he

believed a redesigned solid rocket motor could be ready for flight within

twelve months, and would not require ordering substantial new hardware.

"We can use everything we have, and just modify it," he told the Times.

In particular (though it was not publicly acknowledged at the time), NASA

hoped to be able to use 72 steel casings for the SRM that had been ordered

six months before the Challenger accident. As would become evident

in the course of the accident investigation, NASA had been aware for some

time of problems with the original design of the field joint; these casings

had been planned to accommodate a new joint design incorporating a "capture

fixture" that had been suggested as an improvement on the original joint

design as early as 1981. 22

In its eagerness to get started on the return-to-flight process, NASA

appeared to be getting ahead of the findings and recommendations of the

Rogers Commission, which was not scheduled to report to the President until

early June. For example, Truly had said on March 25 that it was probably

infeasible to add a crew escape pod to the shuttle orbiter, but "certainly

if the Presidential Commission concludes we should do that, we will do

it."23 Particularly troubling to the

Commission was the speed with which a redesign of the SRM field joint was

being proposed. On May 7, the Orlando Sentinel, in an article headlined

"Red Flags Fly Over Joint Redesign," reported that "engineers redesigning

the shuttle's flawed booster joint will submit a preliminary plan to NASA

today, but members of the

Challenger

20. Washington Post, March 12, 1986, p. Al.

21. NASA, "STS 51-L Data and Design Analysis Task Force: Historical

Summary," June 1985, pp. 3-75 and 3-76. In this essay, the term Solid Rocket

Motor(SRM) is used except when the context is clearly one that deals with

the overall Solid Rocket Booster(SRB), which incorporates not only the

SRM but other elements such as parachute recovery systems and an aft skirt

that contains the bolts which bold the Shuttle to the launch pad until

the time of launch.

22. New York Times, March 30, 1986, p. Al, September 22, 1986,

p. Al, and September 23, 1986, p. Al.

23. Ibid. Truly, in an August 14, 1995 personal communication

to the author, notes "I don't remember making a public comment like that

about a crew escape pod, and if I did, it was certainly an ill-advised

statement, since a pod was totally out of the question for several technical,

budgetary, and schedule reasons."

352 RETURN TO FLIGHT

Commission say the agency is moving too fast on the project and could

repeat its mistakes." Some Commission members, the article claimed, "are

so concerned about Marshall botching the redesign that they want an independent

panel of experts to approve the new joint."24

NASA had little choice but to respond to the Commission's concerns,

particularly once they had become public; the agency in the wake of the

Challenger

accident had lost the ability to act counter to those reviewing it from

the outside. The commission's concerns were communicated in a private meeting

with NASA's top officials, and a response followed quickly. On May 9, Truly

announced that James Kingsbury would be replaced as head of the solid rocket

motor redesign team by John Thomas, who had been Spacelab Program Office

manager at Marshall before being assigned to the 51-L Data and Design Analysis

Task Force in March. This was a switch that had been in the works for some

time, but it may have been accelerated by Kingsbury's bullish approach

to SRM redesign. Truly also announced that "an independent group of senior

experts will be formed to oversee the motor redesign" and that this group

would be involved in all phases of the redesign effort, "will report directly

to the Administrator of NASA, and will thoroughly review and integrate

the findings and recommendations" of the Rogers Commission in carrying

out its responsibilities.25 The interactions

between this external panel, which was appointed by the National Research

Council (NRC) in June, and NASA during the redesign and testing of the

SRM would be a key determinant of the pace of the return-to-flight process.

On May 12, Richard Truly got a new boss. James Beggs had long since

resigned as NASA Administrator. The White House, in March, had nominated

James C. Fletcher as his replacement. NASA Administrator from 1971-1977,

the period during which the Space Shuttle had been approved and developed,

Fletcher was quite familiar with the program. It took two months for Fletcher's

nomination to be approved by the Senate. After being sworn in by Vice President

Bush, Fletcher told the press that, if necessary changes to make the shuttle

safe were not completed by the July 1987 target date for the next launch,

"we just won't fly."26

In effect, any chance of a next launch before early 1988 had vanished

with NASA's acceptance of the oversight role of an external advisory group,

though it took several months before the agency fully recognized that reality.

If there had been any prior doubt, it was now clear that the recommendations

of the Rogers Commission, due out in early June, would be the defining

context for NASA's return-to-flight effort, at least in the public mind.

It was clear, moreover, that those recommendations would go well beyond

the need for a redesign of the SRM to many other suggestions on how the

Space Shuttle should be operated and managed; The New York Times commented

that, with such a broad set of recommendations combined with White House

and congressional pressure for full compliance with them, "the complexity

of NASA's [and thus Richard Truly's] task appears to have been greatly

magnified."27

24. Mike Thomas, "Red Flags Fly Over Joint Redesign," Orlando Sentinel,

May 7,1986, p. 1.

25. NASA Release 86-58, "Thomas Assumes Responsibility for SRM Redesign,"

May 9, 1986.

26. Washington Post, May 13, 1986, p. A10. Fletcher brought

with him to NASA some baggage that was to complicate matters in subsequent

months. Before coming to NASA for his first term as Administrator, Fletcher,

a Mormon, had been President of the University of Utah. Congressional critics,

particularly Senator Albert Gore, charged that there was a "Utah conspiracy"

that had resulted, both in the original 1973 choice of the contractor for

the SRB and in the plans for its redesign, in favoritism towards the Utah-based

facilities of Morton Thiokol Inc. This bias, they claimed, was leading

NASA to give limited attention to SRB re-design proposals from contractors

other than Morton Thiokol. In particular, Aerojet had proposed a SRB cast

in one piece, without field joints, that would eliminate the need for a

joint redesign altogether. See coverage of this issue in The New York

Times, July 19, 1986, p. Al; September 23, 1986, p. A23; December 7,1986,

p. Al; December 8,1986, p. Al; and in a December 9, 1996 editorial, p.

A20. According to Richard Truly, these attacks "deeply and personally"

troubled Administrator James Fletcher, "but they really had zero effect

either on the recovery program or the redesign." Personal communication

to author, August 14, 1995.

27. New York Times, June 12, 1986, p. Al.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 353

The Rogers Commission Report

The Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident

(the official name of the Rogers Commission) submitted its report to President

Ronald Reagan on Friday, June 6; the report was released to the public

the following Monday. The over 200-page document, which contained detailed

assessments of the causes of the accident and of NASA's overall failings

related to the mishap, culminated in nine recommendations. Among them were:

Recommendation I - "The faulty Solid Rocket Motor

joint and seal must be changed. This could be a new design eliminating

the joint or a redesign of the current joint and seal." Also, "the Administrator

of NASA should request the National Research Council to form an independent

Solid Rocket Motor design oversight committee to implement the Commission's

design recommendations and oversee the design effort. "

Recommendation II - "The Shuttle Program Structure should

be reviewed. " Also, "NASA should encourage the transition of qualified

astronauts into agency management Positions. "28

Recommendation III - "NASA and the primary shuttle contractors

should review all Criticality 1, 1R, 2, and 2R items and hazard analyses.

"

Recommendation IV - "NASA should establish an Office of Safety,

Reliability and Quality Assurance to be headed by an Associate Administrator,

reporting directly to the NASA Administrator."

Recommendation VI - "NASA must take actions to improve landing

safety. The tire, brake and nosewheel system must be improved. "

Recommendation VII - "Make all efforts to provide a crew

escape system for use during controlled gliding flight. "

Recommendation VIII - "The nation's reliance on the shuttle

as its principal space launch capability created a relentless pressure

on NASA to increase the flight rate ... NASA must establish a flight rate

that is consistent with its resources. "29

In carrying out its mandate, the Rogers Commission had inter-viewed

more than 160 people and held more than 35 formal investigative sessions,

generating more than 12,000 pages of transcripts. The full-time staff grew

to 43, plus some 140 part-time support specialists. In the end, the report

toned down any strong criticism of NASA's overall performance and responsiveness;

such a harsh approach had been proposed by Commissioner Richard Feynman.30

Rather, the report's recommendations were followed by a conciliatory "concluding

thought": "the Commission urges that NASA continue to receive the support

of the Administration and the nation.... The findings and recommendations

presented in this

28. Criticality 1 items were those where a failure could cause loss

of life or vehicle; Criticality 1R, where a failure of all redundant hardware

items could have the same effect; Criticality 2, where failure could cause

loss of mission; Criticality 2R, where failure of all redundant hardware

items could have the same effect.

29. Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident,

Report

to the President, June 6, 1986, pp. 198-201. Other recommendations

dealt with the need to improve internal communications within NASA, particularly

at the Marshall Space Flight Center, and improving maintenance procedures

for Shuttle parts.

30. Washington Post, June 8, 1986, p. Al and New York Times,

June 8, 1986, p. Al. See Richard P. Feynman, "An Outsider's Inside View

of the Challenger Inquiry," Physics Today, February 1988, pp. 26-37

for Feynman's views of the investigation and report. Feynman's critical

views of NASA were published as an appendix to the full Rogers Commission

report, but the volume of the report in which they appeared was not printed

until well after the release of the main text of the report itself.

354 RETURN TO FLIGHT

report are intended to contribute to the future NASA successes that

the nation both expects and requires as the twenty-first century approaches."31

On June 13, President Ronald Reagan directed NASA Administrator Fletcher

to implement the Rogers commission recommendations "as soon as possible,"

and asked for a report within thirty days on a plan for doing so.32

NASA's response came on July 14; Administrator Fletcher told the President

that "NASA agrees with the [Rogers Commission] recommendations and is vigorously

implementing them." On June 20, in a memorandum to Richard Truly, Fletcher

said that he would take direct responsibility for implementing recommendation

IV on a new safety organization to replace what the Rogers Commission had

characterized as NASA's "silent safety program."33

Fletcher told Truly that "the Office of Space Flight is directed to take

the action for all other Commission recommendations." Fletcher asked him

to "status me on your progress on a weekly basis."34

While submitting its report to the President, NASA released a schedule

for the return-to-flight effort that slipped the earliest possible date

for the first launch by 6-8 months, to early 1988. Administrator Fletcher

noted that some within and outside of NASA were urging that the three remaining

Space Shuttles be returned to flight immediately, with constraints on the

conditions under which they could be launched, but that, although he was

"uneasy" and disappointed "about the additional delay," in view of the

large visibility of the accident ... when we start flying again we want

to make sure that it is really safe."35

Implementing the recommendations of the Rogers Commission, and modifying

them when justified, would occupy much of the time of Richard Truly and

his Space Shuttle team for the next twenty-six months. They worked in the

glare of constant congressional and media scrutiny and outside reviews

of their actions. There was little margin for error in their task. This

was in marked contrast to the situation in the months following the Apollo

accident, where, after one round of congressional hearings on the NASA

accident report, the space agency made the required technical and management

fixes without anyone looking over its shoulder. Indeed, NASA in August

1968 even secretly made a decision to send the second post-accident mission,

Apollo

8, around the moon. This decision came before the modified Apollo capsule

had been tested on the October 1968 Apollo 7 flight.

Fixing the Solid Rocket Motor

As mentioned earlier, a Solid Rocket Motor Team based at Marshall (but

including personnel from other NASA centers, particularly Johnson), and

led since May by John Thomas, had gotten an early start on SRM redesign.

Sharing leadership with Thomas was Royce Mitchell, another Marshall engineer.

Working with the NASA team was a parallel group of engineers from the SRM

manufacturer, Morton Thiokol.

This group was headed by Allan J. McDonald, who had been one of those

vociferously opposing the launch of Challenger on the night of January

27. McDonald's testimony to

31. Presidential Commission, Report to the President, p. 201.

32. Washington Post, June 14, 1986, p. A2.

33. Fletcher announced on 8 July that he was establishing a new Office

of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance, reporting directly to the

NASA Administrator. This office would be an internal watchdog with respect

to the actions of Truly's Office of Space Flight. Washington Post,

July 9, 1986, p. A10. Because the operation of this office was outside

of Richard Truly's responsibility during the return-to-flight effort, it

is not discussed in detail here. However, the inputs of the Office of Safety,

Reliability, and Quality Assurance into Truly's management decisions were

clearly an important consideration in that effort.

34. NASA, Actions to Implement the Recommendations of The Presidential

Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, July 14,1986,

pp. v, 43.

35. New York Times, July 15, 1986, p. Al.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 355

the Rogers Commission about the events of that night had brought him

much positive media attention. Following that testimony, however, Morton

Thiokol had reassigned McDonald and another senior engineer who had opposed

the launch, Roger Boisjoly, to jobs not related to the SRM. Congressional

outrage at such a reassignment and NASA pressure had led the firm to restore

McDonald to a central role in the SRM effort.36

The Marshall and Morton Thiokol teams played the central role in developing

an approach to SRM redesign and testing; from late 1986, the team worked

out of temporary quarters near the Morton Thiokol facility in Brigham City,

Utah, north of Salt Lake City. The SRM redesign effort received two overall

directives from Truly's office: most fundamentally, "to provide a solid

rocket motor that is safe to fly," and, secondarily, "to minimize the impact

of the schedule by using existing hardware if it can be done without compromising

safety."37

Thomas revealed on July 2 that the redesign effort was focusing on two

alternatives for fixing the field joint, both of them based on using the

previously ordered castings.38 On

August 12, he announced an over-all plan for SRM redesign, which included

not only changes in the field joint but also fixes to the SRM nozzle-to-case

joint and to the nozzle itself. The redesign proposed for the field joint

incorporated the capture feature that had been discussed since before the

Challenger accident, added a third O-ring, and made other modifications.39

NASA's plan was controversial. For example, the front page of The New

York Times, on September 23, reported "rising concerns that it [NASA] may

be discarding more reliable designs in an effort to save time and hundreds

of millions of dollars."40

Among those with reservations about the path NASA was taking were members

of the NRC Panel on Technical Evaluation of NASA's Redesign of the Space

Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster. This was the external review group that had

been established in June at the urging of the Rogers Commission; the eleven-man

Panel was chaired by H. Guyford Stever, a highly respected engineer who

had been Director of the National Science Foundation and Science Adviser

to President Gerald Ford.

The Stever Panel's first report was submitted to James Fletcher on August

1. It acknowledged that, of the factors driving SRM redesign, "safety is

the prime consideration," but that "the critical national need for the

launch capability of the shuttle makes time a close second." The Panel

expressed early concern that the test program for the redesigned motor

"meets only a minimal requirement."41

Over the next two years, the Stever panel would keep constant pressure

on NASA to explore alternative designs and to conduct an extensive test

program.42 The panel's next report

was submitted on October 10, after NASA had announced its choice for the

redesign of the field joint. The Panel gave only a tepid endorsement to

NASA's plans, noting that "if this approach is successful, i.e., if the

test program succeeds and the level

36. Washington Post, May 4, 1986, p. A4; The New York Times,

June 4, 1986, p. A23.

37. NASA, Report to the President: Implementing the Recommendations

of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident,

June 1987, p. 13.

38. New York Times, July 3, 1986, p. Al.

39. AW&ST, August 18, 1986, pp. 20-21. For a detailed description

of the SRM redesign, see NASA's June 1987 report of how it was implementing

the recommendations of the Rogers Commission cited above.

40. New York Times, September 23, p. Al. See also the Washington

Post, November 10, 1986, p. Al and November 29, 1986, p. A3.

41. Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems, National Research

Council, Collected Reports of the Panel on Technical Evaluation of NASA's

Redesign of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster (Washington, DC:

National Academy Press, 1988), pp. 2, 5. This document is hereafter referred

to as NRC, Collected Reports.

42. Richard Truly remarks that: "Guy Stever and his NRC group were

without doubt the most helpful outside advisors" of "any commission, council,

group, or Congressional committee. They stayed with NASA all the way to

the end, and were constructively critical every time they needed to be."

Personal communication to the author, August 14, 1995.

356 RETURN TO FLIGHT

of safety is judged acceptable, the shuttle flight program can resume

at the earliest time." The Panel expressed some skepticism about the likelihood

of such success, however, urging that "NASA maintain a program to explore

and develop original, possibly quite different designs ... for the contingency

that the baseline design may not offer sufficiently good performance and

margin of safety." It noted that if the design competition had not been

constrained by the desire to use the previously-ordered castings, "we believe

that more basic alternatives to the basic design would probably be preferred

once thoroughly analyzed." The Panel also told NASA "we believe that the

planned test program requires significant augmentation with additional

facilities and tests."43

NASA, after spirited internal debate, concluded that the panel's suggestions

were well-founded, and added a number of partial and full-scale tests to

its plans. On October 16, NASA also announced that it would follow the

Panel's recommendation and build a second facility for full-scale tests

of the SRM.44 NASA did get Panel endorsement

of its decision not to follow one of the Rogers Commission recommendations.

At the urging of member Joseph Sutter of Boeing Aircraft, the Commission

had suggested that the redesigned SRM be tested in a vertical position,

since that was thought to more closely simulate the various conditions

during actual SRM use. Constructing a stand for such a test would have

cost twenty million dollars and added at least a year to the time before

the next shuttle launch. Both the NASA Marshall team under John Thomas

and Allan McDonald at Morton Thiokol argued that a horizontal test could

be conducted in a way that better simulated flight stresses than would

a vertical test. The Stever Panel concurred "that horizontal testing can

be appropriate."45

Between 1986 and August 1988, the NASA-Morton Thiokol team conducted

a test program that included eighteen full-scale but "short burn" tests

of SRM joints; seventy-six tests of subscale motors; fourteen SRM assembly

tests; and five full-duration tests of the redesigned SRM. Flaws in SRM

insulation and seals in joint areas were deliberately introduced in a number

of tests; particularly severe flaws were created for the last full-scale

SRM firing before return to flight, in August 1988. 46

The test program did not always go smoothly, and on occasion produced

results that forced the team to revise their baseline design. As a result,

the date for the first launch slipped twice from a February 1988 target,

to June 1988 and then to the August-September period. Early subscale tests

convinced the team to stay with the original O-ring material, rather than

introduce a substitute. The first full-scale firing was delayed from February

to May 1987. The redesigned joint was first tested in a subscale firing

in early August 1987; the full scale test came on August 30. (Richard Truly's

reaction to the successful test was "a couple of grins.") 47

December 23 test of the new design at temperatures close to those at the

time of the Challenger launch was at first called a success, but

a few days later engineers discovered that the redesigned outer boot ring

at the junction between the SRM nozzle and the rest of the motor had failed.48

After this test, even though it had not identified the specific cause of

the failure, in order to save time the redesign team abandoned the new

design and returned to one that was a modification of the pre-Challenger

design and had performed well in the August test. A successful fourth full-scale

test on the

43. NRC, Collected Reports, pp. 7, 13, 12, and 14.

44. NASA Release 86-146, October 16, 1986,

45. Washington Post, October 3, 1986; NRC, Collected Reports,

p. 10.

46. Allan McDonald, "Return to Flight with the Redesigned Solid Rocket

Motor," AIAA paper 89-2404, July 1989, p. 13.

47. New York Times, August 31, 1987, p. Al.

48. Washington Post, December 30, 1987, p. A1 and January 5,

1988, p. Al.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 357

new test stand that had been suggested by the Stever Panel came in June

1988; it simulated the bending, vibrations, and other stresses of an actual

liftoff.

The final full-scale test came on August 18; it was the most demanding

and controversial of the series. The need for such a test, introducing

the "worst credible" flaw, had been urged on NASA by the Stever Panel as

"essential."49 The redesign team used

a putty knife and shoelaces, among other means, to introduce holes in the

primary SRM seals; these flaws allowed the seepage of gases in order to

check whether backup seals would actually work. Such deliberately induced

major flaws were unprecedented in the history of solid rockets, and "months

of internal debate" within NASA and Morton Thiokol had preceded Richard

Truly's decision to accept the NRC recommendation and approve the politically

very risky $20 million test. (If there had been a failure during the test,

NASA certainly could not have launched Discovery a month later,

even though the test motor contained flaws well beyond anything likely

to appear in Discovery's SRMs.) Although there were some within

NASA who favored the test, most did not; that Truly approved it suggests

the power the Stever Panel had over the character and pace of the return-to-flight

effort.50

As the test ended, Allan McDonald and Royce Mitchell, the NASA engineer

who had shared leadership of the SRM redesign effort with John Thomas,

leapt on the still smoking booster to check for joint failure. There was

no evidence of it. In the crowd watching the test, Truly shouted "we did

it!"51

A few weeks later, a Morton Thiokol spokesman announced that the test

had been "as near perfect ... as you can imagine."52

With that outcome, NASA judged the redesigned SRM ready for use. In its

September 9 report to the NASA Administrator, the Stever Panel concurred,

noting that "risks remain.... Whether the level of risk is acceptable is

a matter that NASA must judge. Based on the Panel's assessment and observations

. . ., we have no basis for objection to the current launch schedule for

STS-26." 53

To its great relief, NASA was now felt both technically and politically

ready to return the Space Shuttle to flight. Successfully redesigning the

solid rocket motor had been the "long pole in the tent" of the return-to-flight

effort; with the muted endorsement by the Stever Panel of the redesign

effort, the last obstacle to an initial post-Challenger flight had

been removed.

One person close to the program suggested that the redesign and testing

work between early 1986 and August 1988 "exceeded, by four or five times,

the amount of work put into original motor work in the mid-1970s." 54

While Richard Truly was necessarily removed from the day-to-day engineering

details of the enterprise, he at its outset focused efforts on only those

redesign activities that were mandatory for requalifying the SRM for use

on the first post-accident flight, and resisted pressures from many fronts

to introduce changes, including new designs, additional tests, and different

contractors, that would

49. The recommendation came in the June 22, 1987 panel report to Administrator

Fletcher. See NRC, Collected Reports, p. 27.

50. Washington Post, August 19, 1988, p. A3. Truly remarks that,

after the "fierce" internal debate, he decided that the Stever panel was

correct, and that the risk of the test was "worth taking." He also suggests

that "I wouldn't have hesitated to go the other way had I believed that

they were wrong." Personal communication to author, August 14, 1995.

51. Ibid.

52. New York Times, August 31, 1988.

53. NRC, Collected Reports, p. 58.

54. Morton Thiokol assistant general manager for space operations Richard

Davis, quoted in AW&ST, September 26, 1988, p. 17.

358 RETURN TO FLIGHT

have delayed resumption of shuttle flights even more. 55

Truly defended the NASA-Morton Thiokol effort to a sometimes hostile Congress.

He accepted the risk that the proposed "minimum necessary change" approach

to redesign would not be successful, and authorized ordering SRMs incorporating

the baseline design changes for the first post-Challenger flights

at the time the redesign reviews were completed, but before major tests

of the redesign had begun. If there had been a major design failure in

the test program, NASA would have had to go back to square one, and those

SRMs redesigned or scrapped.56 When

the pre-launch test program concluded with the August 18 success, Richard

Truly had reason to be excited.

A New Management Structure

Putting a new management structure in place was second in importance

to redesigning the SRM as a prerequisite to clearing the Space Shuttle

for its return to flight. Richard Truly made a reassessment of the entire

shuttle program management structure the first item in his return-to-flight

strategy in March 1986, and the Rogers Commission listed such a review

as its second recommendation. In May 1986, newly reinstalled NASA Administrator

Fletcher had charged the former manager of the Apollo program, retired

General Samuel Phillips, with conducting an overall review of NASA organization

and management. On June 25, Truly directed astronaut Robert Crippen to

form a fact-finding group specifically responsible for assessing the National

Space Transportation System (NSTS) management structure.

A first step in reforming program management was the departure or transfer

of a number of those who had been in key management positions at the time

of the Challenger accident. By October 1986, there were new directors

at the Johnson, Marshall, and Kennedy Centers, and several other individuals

at Marshall who participated in the decision to launch Challenger

had left NASA.

The Crippen group submitted its findings in August. They were consistent

with the views of the Phillips review, and so on November 5, after extensive

consultations within NASA, Truly announced a new shuttle management structure.57Aviation

Week described it as "resembling that of the Apollo program, with the

aim of preventing communication deficiencies that contributed to the

Challenger

accident."58

The key management change was moving lead responsibility for the shuttle

from the Johnson Space Center to NASA Headquarters in Washington. Arnold

Aldrich, who had

55. NASA diverted some of the pressure for involving firms other than

Morton Thiokol in the SRM redesign effort by announcing on 18 July 1986

that it would seek to develop a second-generation Advanced Solid Rocket

Motor for use beginning in the early 1990s, and that the competition to

build this booster would be an open one. The New York Times, July

19, 1986, p. Al. NASA also asked other solid rocket manufacturers to critique

the Morton Thiokol redesign, but this did not totally relieve Congressional

and industry pressure for a more broadly-based redesign effort. AW&ST,

February 9, 1987, pp. 116-17.

56. As it was, NASA had to retrofit the SRMs intended for use in the

STS-26 mission with the design for the SRM nozzle outer boot ring that

had been tested in the August 1987 full-scale firing; the boosters had

been built with the design that had failed in the December test. This change

took almost three months and was a primary reason why the STS-26 launch

had to be delayed until August or September 1988. NASA did not know whether

the December failure was due to a faulty design or to a demanding test

that had been performed at the end of the test firing. Rather than wait

for the results of an analysis to determine which was the case, NASA, wanting

to launch the Shuttle as soon as possible, chose to go with a modification

of the pre-Challenger design. AW&ST, January 4, 1988,

p. 22 and January 11, 1988, p. 24.

57. Memorandum to Distribution from M/Associate Administrator for Space

Flight, "Organization and Operation of the National Space Transportation

System (NSTS) Program," November 5, 1986.

58. AW&ST, November 10, 1986, p. 30.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 359

been NSTS manager in Houston, was asked by Truly to come to Washington

as Director, NSTS in effect, the single director of the Space Shuttle

Program, with all shuttle-related activities at the Johnson, Marshall,

and Kennedy Centers reporting to him. He in turn would report directly

to Truly. Aldrich, who was the only top-level shuttle manager who retained

his position after the Challenger accident, would have two deputy

directors, one for the NSTS Program based at Johnson, and one for NSTS

Operations, based at Kennedy. Richard Kohrs was named to the first deputy

position; Robert Crippen, the second. The Director, NSTS would have "approval

authority for toplevel program requirements, critical hardware waivers,

and for budget authorization adjustments .... "59

Truly in his memorandum also noted that "a key element in the ultimate

success of the Office of Space Flight is a revitalization of the OSF Management

Council."60 This body included the

Associate Administrator for Space Flight and the Directors of Johnson,

Kennedy, and Marshall (and the much smaller National Space Technology Laboratories).

It had not been very active in the pre-Challenger period. This top-level

group, lead by Truly, began to meet on a monthly basis, and served as the

forum for overseeing the return-to-flight effort in the months following.

Its meetings were described as "free-wheeling, no-holds-barred," at which

"programme issues are flushed into the open and relentlessly pursued to

resolution."61

A secondary aspect of the Rogers Commission recommendation on management

changes was that "NASA should encourage the transition of qualified astronauts

into agency management positions." Richard Truly was himself a former astronaut,

and it might have been expected that implementing this recommendation would

have been a straightforward matter.

The reality turned out to be somewhat different. In the wake of the

Challenger

accident, the public discovered that the image of the astronaut corps was

very much at odds with reality, and that the group was racked with "longstanding

strains and resentments," and with "low morale, internal divisions, and

a management style that uses flight assignments as a tool to suppress discussion

and dissent."62 Chief astronaut John

Young, who had commanded the first shuttle mission, was particularly critical

of NASA's approach to flight safety. 63

Truly's first challenge, then, was rebuilding a positive attitude among

his former astronaut colleagues. He met with them privately in March 1986,

and made sure that Crippen considered astronaut views as he reviewed shuttle

program management. He was not totally successful; some in the astronaut

office believed he was too ambitious in trying to return the shuttle to

flight by February 1988, and was planning on too many launches per year

once the shuttle was back in operation. They were critical of the measured

pace of the recovery effort, given a launch target only sixteen months

in the future, pointing out that after the Apollo 1 fire, the command

module was redesigned in only eighteen months and suggesting that "management

has either got to cut back what they want to do before restarting flights,

or get a 'tiger team' approach to pick up momentum."64

By July 1987, NASA noted that "ten current or former astronauts hold

key agency management positions."65

One of them had been Rick Hauck, who served from August 1986 to January

1987 as NASA's Associate Administrator for External Relations before he

returned to Houston to train for the STS-26 mission. It was rather well

known that Hauck was likely to command the first post-accident shuttle

flight; he was thus a convincing spokesman for the safety

59. Richard Truly memorandum, November 5,1986.

60. Ibid.

61. L.J. Lawrence, "Space Shuttle-Return to Flight," Spaceflight,

September 1988, p. 352.

62. New York Times, April 3, 1986, p. B9 and Washington Post,

April 1, 1986, p. Al.

63. See, for example, Memorandum from CB/Chief, Astronaut Office to

CA/Director, Flight Crew

Operations, "One Part of the 5 1-L Accident-Space Shuttle Program Flight

Safety," March 6, 1986.

64. AW&ST, October 20,1986, pp. 34-35.

65. NASA, Implementation of Recommendations, July 1987, p. 32.

360 RETURN TO FLIGHT

aspects of the return-to-flight effort. Other astronauts brought into

management positions had "some difficulties in adjusting to the realities

of bureaucratic life," but felt that "their presence had made a difference,

pointing with pride to influence on key policy issues."66

Other Changes to the Shuttle

Even before the Rogers Commission submitted its report, Richard Truly

made one key decision related to reducing the risks of future shuttle operation.

Some in NASA, even before the accident, were concerned about the wisdom

of using a modified Centaur rocket, fueled by highly combustible liquid

hydrogen, as an upper stage to carry satellites from the shuttle's payload

bay to other orbits. Among the payloads for which the Centaur was to be

used were two solar system exploration missions, Ulysses to explore

the Sun's polar regions and Galileo to orbit Jupiter; several classified

Department of Defense payloads were also scheduled to employ the Centaur

upper stage.

A combination of congressional pressure and the more stringent safety

criteria being applied to the shuttle after the accident led to a NASA

reassessment of Centaur. Although over $700 million had already been spent

on modifying the Centaur for shuttle use, and its unavailability would

cause major delays in the solar system exploration program, Truly recommended

cancelling the Shuttle Centaur program. Administrator Fletcher agreed and

announced the decision on June 19, 1986. 67

Another key decision was to terminate planning for launching the shuttle

into polar orbit from the Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. This

decision meant that the very expensive Shuttle Launch Complex 6 at Vandenberg

would be mothballed and that the number of overall Department of Defense

(DoD) flights on the shuttle reduced (DOD would use a Titan IV expendable

launch vehicle for payloads originally scheduled for a shuttle launch from

Vandenberg). This decision reduced overall schedule pressure on a four-orbiter

shuttle fleet, and eliminated the need for a lighter, filament-wound SRM

case.68

The third recommendation of the Rogers Commission had directed NASA

and its industrial partners to review, in terms of safety and mission success,

all Criticality 1, 1R, 2, and 2R items and hazard analyses. Richard Truly

had called for an even more extensive risk review in his March 1986 return-to-flight

strategy. The Rogers Commission had also separately recommended a series

of actions to improve landing safety.

That the shuttle had been flying with a number of less-than-optimum

systems and components was well known to those close to the program, but

the pressures of maintaining an ambitious launch schedule and budget constraints

had blocked any extensive review and upgrading of the shuttle before the

accident. When it became clear that the shuttle would be grounded for some

time, Arnold Aldrich, at the time still in charge of the shuttle program

at the Johnson Space Center, had on March 13, 1986, initiated a comprehensive

review aimed at identifying possible shuttle upgrades. By the end of May,

this review had identified "44 potentially [critically] flawed components

of the space shuttle ... that may have to be fixed before shuttle flights

can resume."69

The conduct of a comprehensive Shuttle Failure Modes and Criticality

Analysis and the audit of the resulting Criticality 1 and 2 items recommended

by the Rogers Commission was an extensive and complex process. In its July

1986 report on implementation of the

66. New York Times, June 2, 1987, p. C2.

67. New York Times, June 20, 1986, p. Al.

68. Comment on draft of this essay by Richard Kohrs, July 19, 1995.

69. Washington Post, May 28, 1986, p. A5.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 361

Rogers Commission recommendation, NASA indicated that "the overall reevaluation

is planned to occur incrementally and is scheduled to continue through

mid-1987. "70 By the time Discovery

was ready for launch, the list of Criticality 1 items had grown from the

617 items at the time of

Challenger to 1,568; each of those items

had to pass particularly rigorous review before Discovery was cleared

for flight. The number of Criticality 1R items had also grown dramatically,

from 787 to 2,106 .71

Similar to his situation with respect to SRM redesign, Richard Truly

found an external review committee assessing NASA's actions with respect

to risk assessment and management. The National Research Council created

a Committee on Shuttle Criticality and Hazards Analysis Audit in September

1986; the Committee was chaired by retired Air Force General Alton Slay.

In its initial report, submitted to James Fletcher on January 13, 1987,

the Slay Committee noted that it had "been favorably impressed by the dedicated

effort and extremely beneficial results obtained thus far." The Committee

raised a point that recurred throughout its work, that "the present decision-making

process within NASA ... appears to be based on the judgment of experienced

practitioners and has received very little contribution from quantitative

analysis." The Committee also questioned the timing of the risk review

in terms of incorporating any resulting design changes in the shuttle before

its scheduled return to flight (then February 1988), noting that there

may not be "time to incorporate any substantial design changes that may

be indicated by the outcome" of the review.72

The Slay Committee continued its work throughout 1987 and submitted

its final report to Administrator Fletcher in January 1988, although the

report was not made public for two months. While generally positive in

tone, it criticized NASA's risk assessment activities as still too "fragmented"

and "subjective," and for not taking advantage of widely used quantitative

techniques such as probabilistic risk assessment. 73

But, most important to Richard Truly and his associates, the Committee

found "absolutely no show-stoppers" from a risk assessment perspective

in terms of NASA's return-to-flight plans.74

Richard Truly had relieved much of the pressure of implementing the

separate Rogers Commission recommendation on improving landing safety by

mandating in his March 24, 1986, return-to-flight strategy that the first

flight would land on one of the extremely long runways at Edwards Air Force

Base in the California desert. In its 1987 report to the President, NASA

said that it had identified several design improvements "to improve the

margins of safety for the landing/deceleration system. Some of these improvements

are modifications to existing designs and will be completed prior to the

next flight." But, added NASA, improvements involving more extensive design

changes would have to be certified for flight and then introduced "later

in the program."75

In fact, this was the philosophy followed for almost all design changes

to the shuttle in the aftermath of the Challenger accident which were not

related to SRM redesign. The first post-accident shuttle flight was launched

as soon as possible after the requalification

70. NASA, Actions to Implement the Recommendations, July 14,

1986, p. 19.

71. Washington Post, August 23,1988, p. A3; NASA, "NSTS SR&QA

Assessment," September 13-14,1988.

72. National Research Council, Committee on Shuttle Criticality Review

and Hazards Analysis Audit, Post-Challenger Evaluation of Space Shuttle,

Risk Assessment and Management, (Washington, DC: National Academy Press,

January 1988), pp. 98-100.

73. This was not a new criticism of NASA. Staff of the White House

Office of Science and Technology had made similar criticisms in 1962 as

NASA evaluated various ways of carrying out a manned mission to the moon.

See John M. Logsdon, "Selecting the Way to the Moon: The Choice of the

Lunar Orbital Rendezvous Mode," Aerospace Historian, June 1971.

74. Washington Post, March 5, 1988, p. A6; New York Times,

March 5, 1988, p. B2; Science, March 11, 1988, p. 1233.

75.NASA, Implementing the Recommendations, July 1987, pp. 55-56.

362 RETURN TO FLIGHT

of the SRM for flight; the introduction of other redesigned shuttle

elements as a result of the risk reviews or of Arnold Aldrich's examination

of desirable shuttle improvements did not have significant influence on

the shuttle launch schedule. However, the post-Challenger reviews

did have other important impacts, both before and after return to flight.

The system was overall much safer and reliable on September 29, 1988, than

it had been in the 1981-1986 period. The shuttle's main engines were upgraded,

its brakes improved, and the valves in the orbiter that controlled the

flow of fuel to the orbiter's engines modified to prevent accidental closure.

But the result was a "shuttle in transition"; "the hard truth," said Aldrich,

" is that the really major changes take years."76

Adding an Escape System

As a former astronaut, Richard Truly gave particular, personal attention

to the Rogers Commission recommendation that an escape system be added

to the shuttle to allow its crew to leave the vehicle in an emergency while

it was in controlled gliding flight (i.e., after the SRMs had finished

firing and been jettisoned and the shuttle's main engines shut down). In

fact, a search for a viable escape system had begun in March 1986; as the

search progressed astronaut Bryan O'Connor played a key role in assessing

various options. Alternatives considered included ejection seats, "tractor

rocket" extraction of seated crew members, bottom bail out, and tractor

rocket extraction through the side hatch. All but the last alternative

were eliminated by the end of 1986, but in its July 1987 report to the

President on how it was implementing the Rogers Commission recommendations,

NASA said that a decision to implement the side hatch, rocket-powered escape

approach "had not been made." 77

NASA in December 1986 had in fact made a tentative decision to go forward

with this approach, if it could be shown satisfactory in tests and installed

in time for the next launch.78 By

September 1987, due to delays in the testing program and the possibility

that an adequate supply of parts for the system might not be available

on a timely basis, NASA began to consider a simpler alternative-one using

a telescoping metal pole extending nine feet beyond the shuttle escape

hatch. In an emergency, crew members would attach themselves to the pole

and slide away from the shuttle orbiter's wing before they parachuted to

Earth.79

Based on tests of the two systems, Truly in April 1988 selected the

pole escape approach. This was perhaps the last major pre-launch choice

stemming from a Rogers Commission recommendation. One factor in the decision

was avoiding the additional risks created by installing the pyrotechnic

tractor rockets in the shuttle cabin; also, the STS-26 crew preferred the

pole system. The escape system could be used only with the shuttle in controlled

flight at a less than 20,000 foot altitude, with landing on a primary or

emergency runway impossible. (Whether in an emergency to push the shuttle's

main engines beyond their design limits to enable the orbiter to reach

a trans-Atlantic abort site, or to bail out was a controversial issue up

almost to the time of the Discovery launch. Astronauts and mission

controllers favored a bail out option, but they were overruled by Truly

who wanted to avoid losing another orbiter in an ocean ditching.)80

Bailing out of the shuttle was considered far preferable to trying to survive

a water landing; one individual responsible for the escape system commented,

"the orbiter doesn't survive ditching very well."81

76. New York Times, December 28, 1986, p. 1.

77. NASA, Implementing the Recommendations, p. 67.

78. AW&ST, January 5, 1987, p. 27 and July 6, 1987, p. 28.

79. AW&ST, September 7,1987, p. 125.

80. AW&ST, September 26,1988, p. 63.

81. Ibid., April 11, 1988, p. 31.

FROM ENGINEERING SCIENCE TO BIG SCIENCE 363

Setting a Flight Rate

The Rogers Commission had identified "the relentless pressure to increase

the flight rate" as a major contributing factor to the Challenger

accident. Though not directly related to getting the shuttle ready for

its first post-accident flight, determining the appropriate schedule for

shuttle launches after the STS returned to flight occupied much of the

time of Richard Truly and his staff at NASA Headquarters while the shuttle

was grounded.

A first consideration was what payloads the shuttle would carry as the

launch rate was reduced; it was clear that critical national security payloads

would have first priority. After a series of intense debates within the

Reagan administration-over NASA's objections-the President announced on

August 15, 1986, that, except in situations where there were overriding

national security, foreign policy or other reasons, the shuttle would no

longer be used to launch commercial communication satellites.82

This decision and plans for its implementation announced two months later

removed a major category of payloads from the shuttle manifest; prior to

the accident, eleven of the twenty-four earlier shuttle missions had carried

one or more commercial communication satellites.

In October 1986, NASA released a shuttle launch schedule that called

for a buildup to fourteen or sixteen launches per year, four years after

the STS returned to flight, and after a replacement orbiter had entered

service.83 This was more ambitious

than the launch rate thought reasonable by yet another National Research

Council review committee. At the request of NASA's House Appropriations

Subcommittee, the NRC created a panel to carry out a "post-Challenger

assessment of Space Shuttle flight rates and utilization." In its October

1986 report, the panel concluded that with a four-orbiter fleet NASA could

sustain a launch rate of eleven to thirteen launches per year, but only

if there were significant improvements in various aspects of the shuttle

program. Without such improvements, the panel estimated, the maximum rate

was eight to ten launches per year. The panel noted that only "under special

conditions" might the launch rate surge to fifteen launches per year.84

Balancing the desire to get flying again on a regular basis, the pressure

to launch critical national security and scientific payloads as soon as

possible, and the need to ensure continued safe and reliable operation

of the Space Shuttle was a constant challenge for Richard Truly. He recognized

that "we will always have to treat it [the shuttle] like an R&D test

program, even many years into the future. I don't think calling it operational

fooled anybody within the program.... It was a signal to the public that

shouldn't have been sent and I'm sorry it was."85

Media watchdogs were quick to report perceptions that NASA was "putting

schedule over safety."86 But, as Truly

had said on many occasions, "the only way to operate the shuttle with zero

risk is to keep it on the ground." That was not his intent.

Return to Flight

The Space Shuttle Discovery was rolled out from the Vehicle Assembly

Building to launch pad 39B on July 4, 1988; as a morale-boosting measure,

throughout the day Kennedy Space Center workers and their families were

allowed to drive around the pad.

82. Ibid., August 18,1986, pp. 18-19.

83. Ibid., October 13, 1986, pp. 22-23.

84. National Research Council, Committee on NASA Scientific and Technical

Program Reviews, Post-Challenger Assessment of Space Shuttle Right Rates

and Utilization (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, October 1986),

pp. 7-8.

85. AW&ST September 26,1988, p. 16.

86. Time, February 1, 1988, p. 20.

364 RETURN TO FLIGHT

There were no waivers (permissions to launch even though specifications

were not met) on any hardware element, and an internal NASA committee had

found a "positive change in attitude" with respect to safety considerations

and a "healthy redundancy of safety reviews and oversights." The group

found no safety issues that would adversely affect the launch of STS-26,

then set for September 6. 87