On Oct. 3, 1962, astronaut Walter M. “Wally” Schirra completed America’s third and then-longest orbital spaceflight during the Mercury-Atlas 8 mission. Naming his spacecraft Sigma 7, Schirra completed six orbits of the Earth, conducting engineering tests of his spacecraft and several experiments including photography of the planet. After he made the first splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, recovery teams brought Sigma 7 with Schirra inside aboard the prime recovery ship the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Kearsarge. From there, Schirra returned to Houston by way of Hawaii. He described his mission as a “textbook flight” during a press conference at Houston’s Rice University. His hometown of Oradell, New Jersey, feted him with a parade and President John F. Kennedy hosted him at the White House.

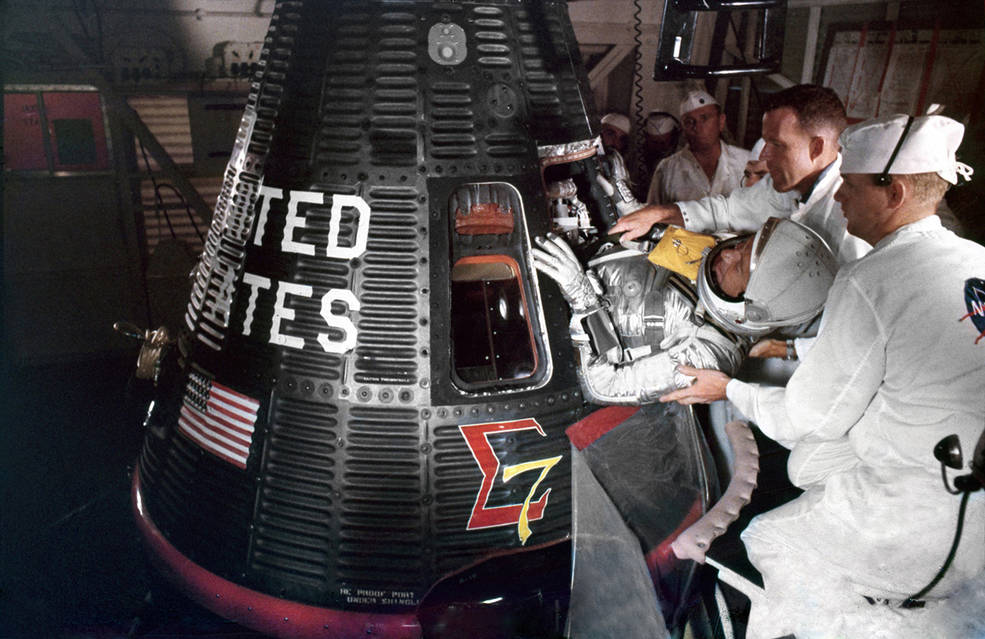

Left: Astronaut Walter M. “Wally” Schirra, the prime astronaut assigned to the Mercury-Atlas 8

mission. Middle: Astronaut L. Gordon Cooper, assigned as Schirra’s backup. Right: Workers

prepare Schirra’s Mercury capsule in Hangar S at Cape Canaveral, Florida.

On June 27, 1962, NASA announced that Schirra would fly six orbits during the nine-hour Mercury-Atlas 8 mission, with L. Gordon Cooper serving as his backup. Following the tradition of earlier Mercury astronauts, Schirra named his capsule Sigma 7, after the Greek letter Σ often used in engineering and mathematics to symbolize summation, and the “7” representing the seven Mercury astronauts. Schirra chose Sigma to represent the summation of work by thousands of scientists and engineers across the country to make Project Mercury a reality. After his Mercury spacecraft’s arrival in January 1962, some of those very engineers in Cape Caneveral’s Hangar S prepared it for flight. Others readied the Atlas rocket after its arrival at Launch Pad 14 on Aug. 13.

Left: Static fire at Launch Pad 14 of the Atlas rocket prior to installation of the Mercury capsule.

Middle: Pad workers lift the Mercury capsule for mounting atop the Atlas rocket. Right: Astronaut

Walter M. Schirra, left, tours President John F. Kennedy at Cape Canaveral’s Launch Pad 14.

On Sept. 9, workers at Launch Pad 14 successfully carried out an 11-second static firing of the Atlas rocket’s engines to verify a new fuel feed system. The next day, workers hoisted the Mercury capsule and installed it atop the rocket. On Sept. 11, during his visit to Cape Canaveral as part of his two-day whirlwind tour of space facilities that also included his famous speech at Rice University in Houston, President John F. Kennedy viewed the assembled rocket, with Schirra serving as his tour guide. Meanwhile, halfway around the world, recovery forces of the U.S. Navy, led by the prime recovery ship the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Kearsarge (CVS-33), assembled northeast of Midway Island, Schirra’s expected splashdown point after a full six-orbit mission. Other ships deployed to backup recovery zones in the Atlantic Ocean in the event the mission ended early.

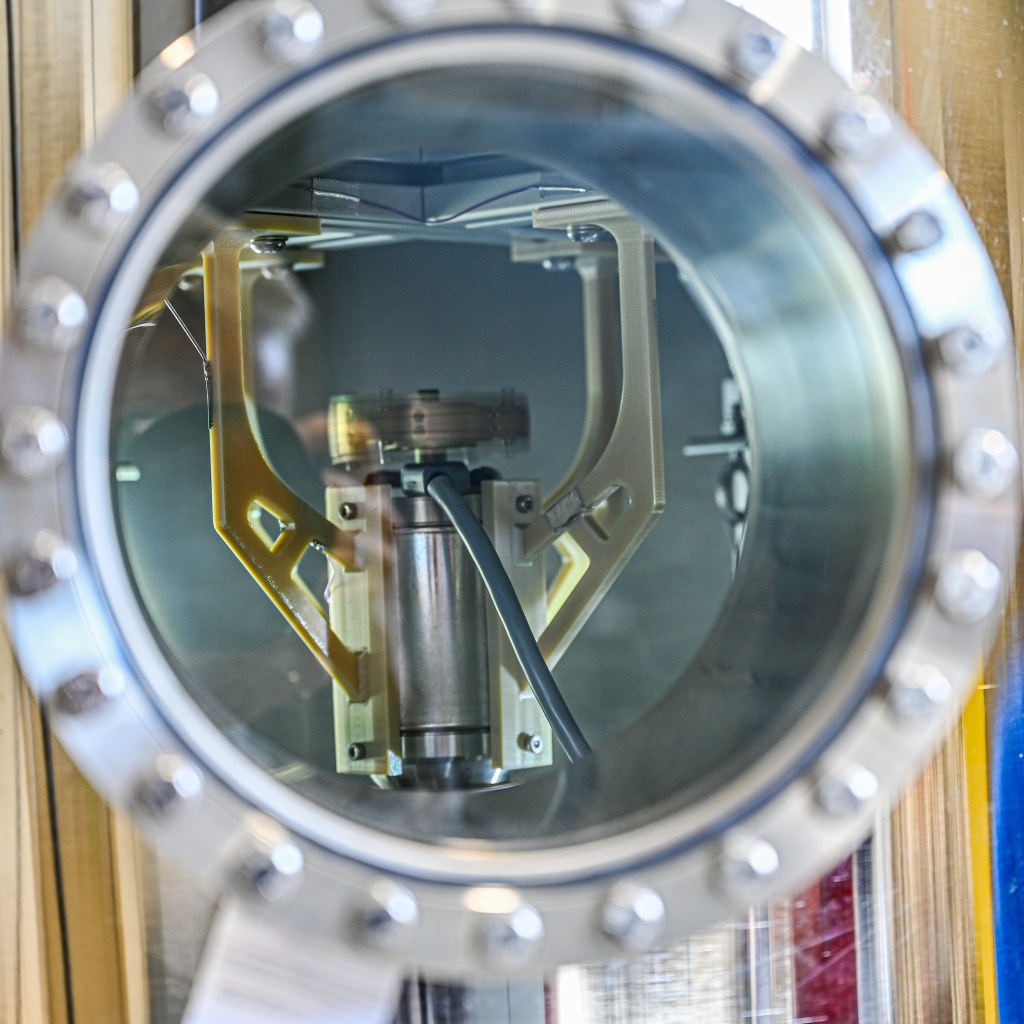

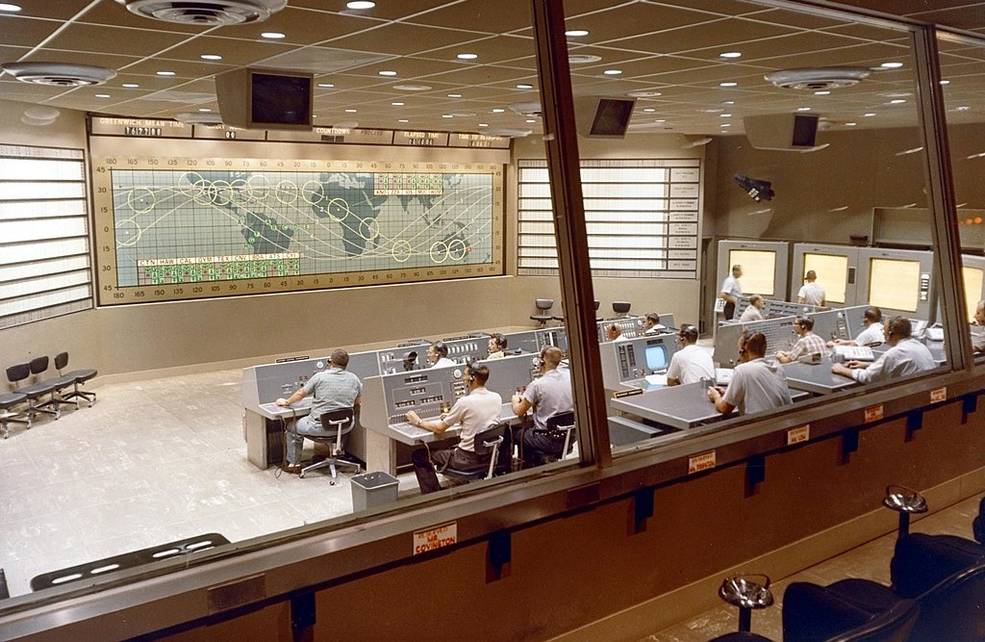

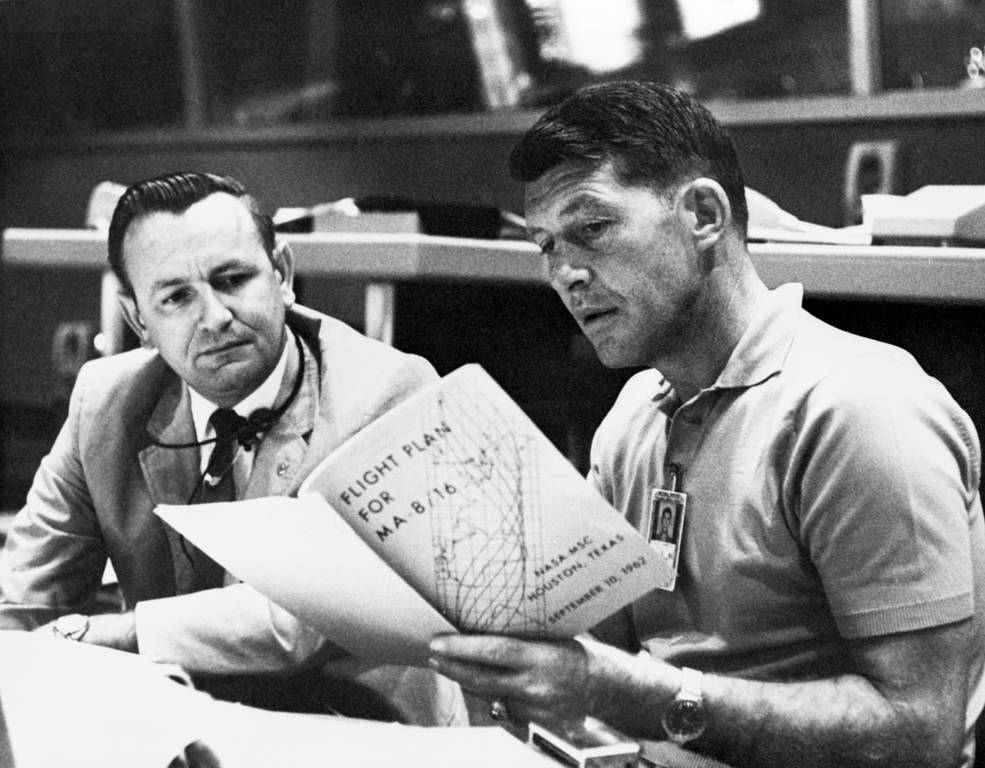

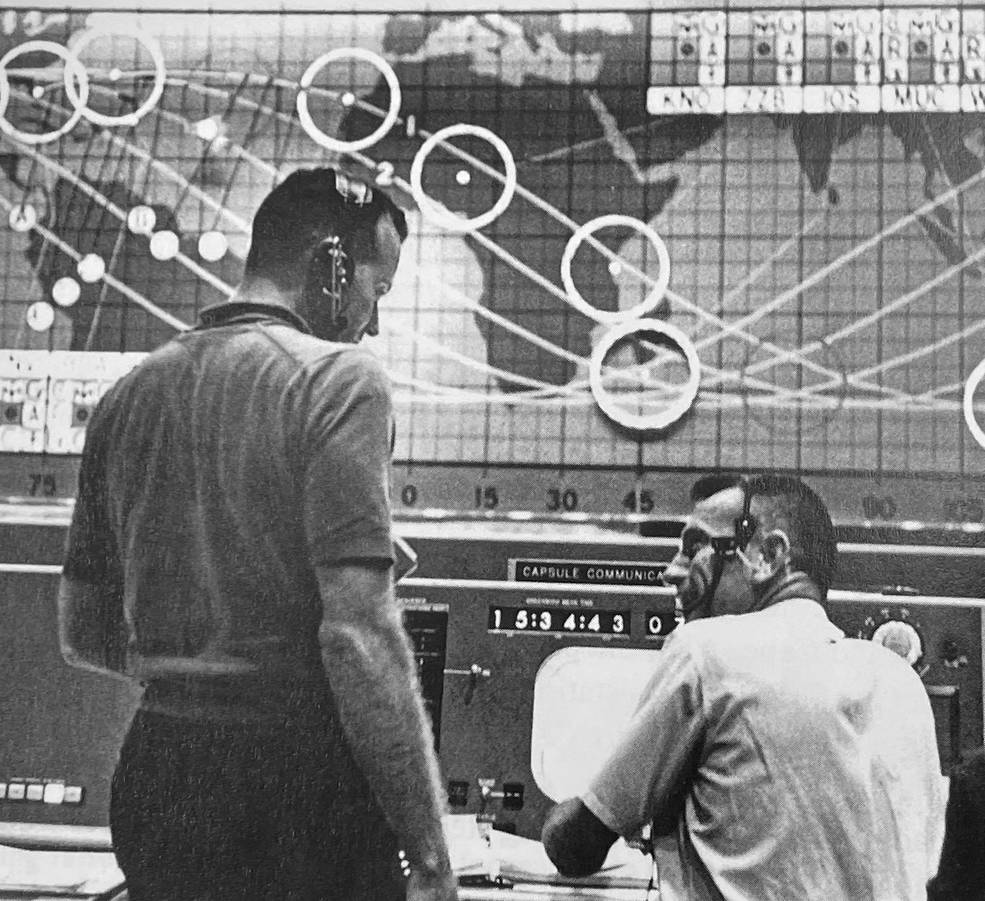

Left: A preflight simulation of the Mercury-Atlas 8 mission at the Mercury Control Center (MCC)

at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, in Florida.

Middle: Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft, left, and astronaut Walter M. Schirra

review the Mercury-Atlas 8 flight plan. Right: Backup Mercury-Atlas 8 astronaut L.

Gordon Cooper, left, and capsule communicator (capcom) astronaut Donald

K. “Deke” Slayton confer in the MCC.

Schirra participated in preflight tests of his mission in the Mercury spacecraft simulator and with the controllers in the Mercury Control Center (MCC) at Cape Canaveral. Led by Flight Director Christopher C. Kraft, these simulations gave the controllers the proficiency to react to any unforseen situation during the mission. Astronaut Donald K. “Deke” Slayton served as the capsule communicator, or capcom, the controller who talked directly with the astronaut during the mission. Backup astronaut Cooper assisted Slayton. Other astronauts deployed to tracking stations around the world to support Schirra’s mission.

Left: Artist Cecilia “Cece” Bibby, left, paints the Sigma 7 logo onto the Mercury spacecraft

as astronaut Walter M. Schirra looks on. Middle: Schirra, center, trains on the use of

the handheld camera. Right: Schirra suits up for launch and talks with Coordinator of

Astronaut Activities Donald K. “Deke” Slayton.

Schirra’s mission included engineering tests of the Mercury spacecraft to demonstrate that it could operate beyond its original design specification of three orbits, and to bridge the gap to an ultimate day-long Mercury mission. The flight plan also included four science experiments, of which Schirra operated two, including photography of the planet using a Hasselblad handheld camera modified for use in space.

Left: Astronaut Walter M. Schirra departs Hangar S at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, now

Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, for the ride to Launch Pad 14. Middle: Schirra,

accompanied by his backup L. Gordon Cooper, exits the transfer van after arriving

at Launch Pad 14. Right: Schirra, assisted by Cooper and pad

technicians, climbs aboard Sigma 7.

In Cape Canaveral’s Hangar S, Schirra’s flight surgeon awakened the astronaut in the pre-dawn hours of Oct. 3. After a brief physical, Schirra ate the now-traditional steak-and-eggs breakfast and donned his silver spacesuit. He dozed off for a few minutes during the ride to the launch pad, then rode the elevator to the spacecraft level where Cooper and pad leader Guenther Wendt helped him into the capsule and sealed the hatch. The countdown proceeded smoothly except for a brief hold to correct a technical issue at the Canary Islands tracking station.

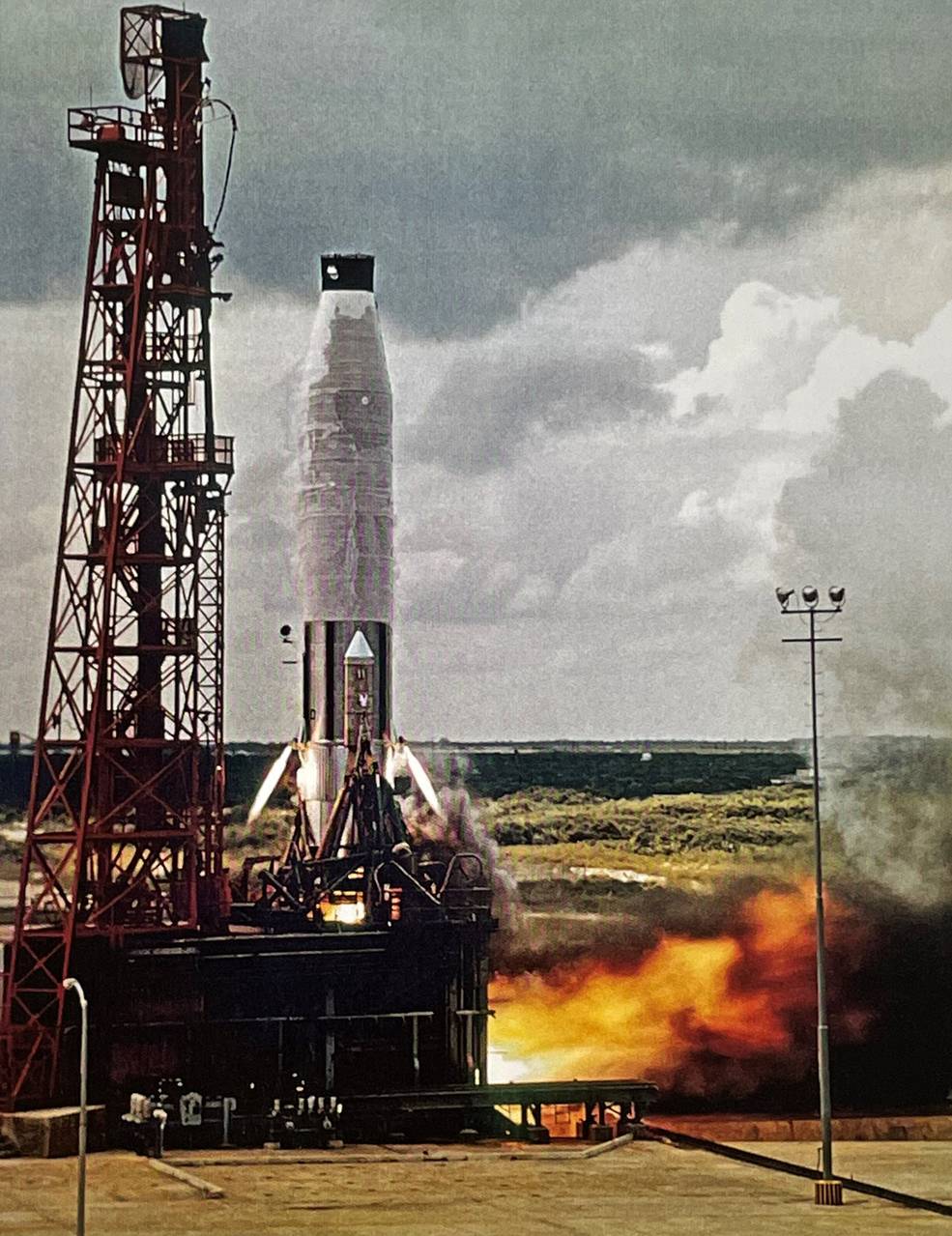

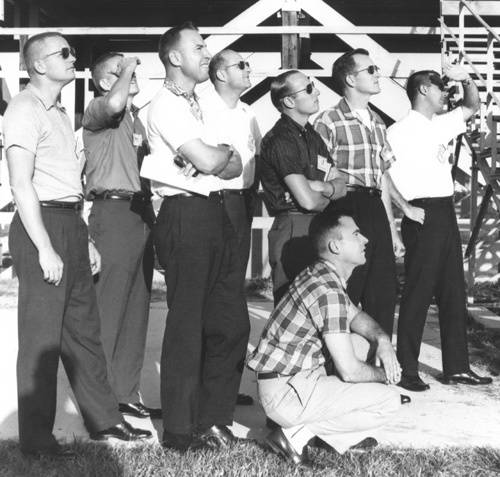

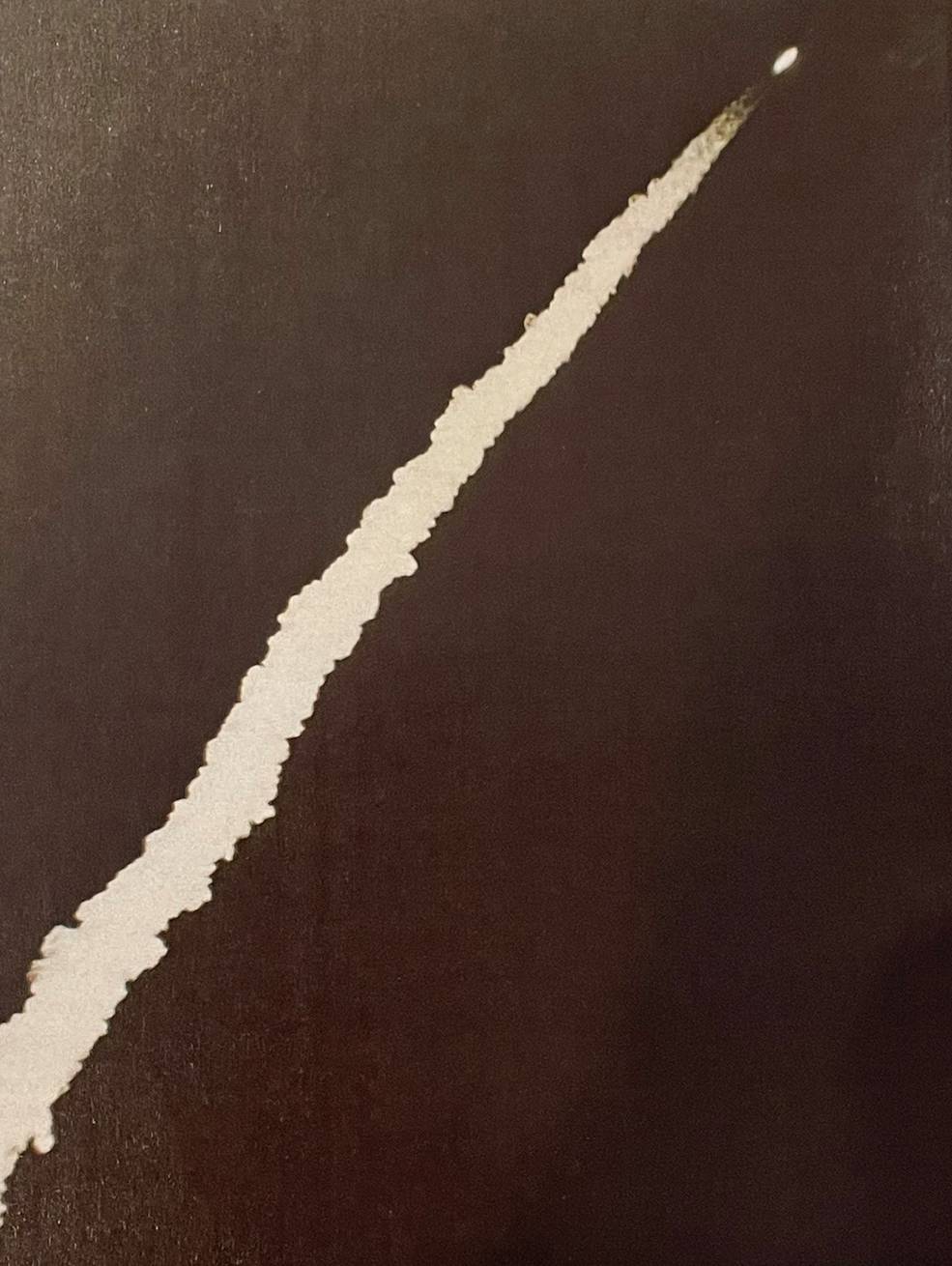

Left: Eight of the nine newly-selected Group 2 astronauts watch the launch of astronaut

Walter M. Schirra aboard Sigma 7. Middle: Liftoff of Mercury-Atlas 8 carrying Schirra

into orbit. Right: Long-range camera view of the ascent of Mercury-Atlas 8.

Cape Canaveral hosted some very special guests to witness Schirra’s launch. Eight of the nine new astronauts selected by NASA just two weeks earlier watched as the countdown ticked down to zero and the Atlas rocket carrying Schirra lifted off. Schirra reported to capcom Slayton in the MCC, “I have the liftoff. Clock had started, and she feels real nice.” While the ascent appeared normal to Schirra inside the capsule, ground controllers noticed that the Atlas rocket began to roll at a rate greater than planned. They grew concerned that if the roll persisted, it might cause the rocket to veer off course, triggering an abort and bring Schirra’s flight to a swift and premature end. Soon, the roll stopped, and the flight proceeded as planned, with the two Atlas booster engines shutting down a little more than two minutes after liftoff. The single sustainer engine continued to fire for three more minutes, placing Sigma 7 with Schirra inside into an elliptical 100-by-175-mile orbit, traveling at 17,557 miles per hour. Schirra’s spacecraft separated from the spent rocket, and he turned his capsule around so its blunt heatshield and attached retrorocket pack faced in the direction of flight. Schirra placed the spacecraft into autopilot mode to save fuel and watched the slowly tumbling rocket fade into the distance. He successfully dealt with his first in-orbit problem when his suit began to overheat, causing concern that mission controllers might cut the flight short. But Schirra had a procedure for dealing with the problem, and with the suit temperature returning toward normal, Flight Director Kraft gave a go for the second orbit, allowing the mission to proceed.

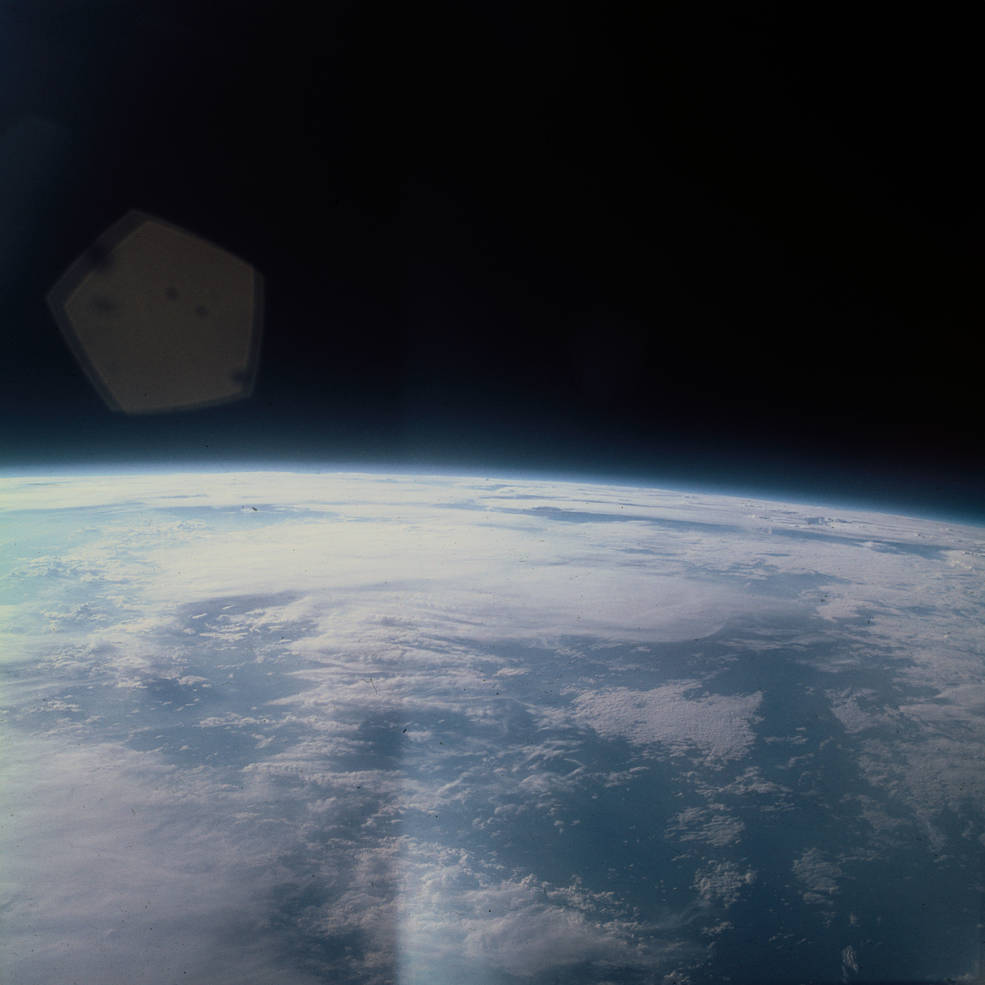

Left: Still from a film of astronaut Walter M. Schirra during his six-orbit flight.

Middle: Schirra’s photograph of South America. Right: Schirra’s photograph

of cumulus clouds.

During the second orbit, Schirra conducted tests of the attitude control system, and to conserve fuel, he put the spacecraft into free drift mode on the third orbit. He took a few photographs of the Earth, as the spacecraft’s attitude allowed. The next three orbits transpired without incident, and Schirra began preparing for the all-important retro-fire. He manually oriented Sigma 7, and then returned the spacecraft to automatic control. The retrorockets fired precisely on time to bring Schirra and his spacecraft out of orbit. As the capsule entered the atmosphere, the plasma cloud formed around it prevented communications with the ground for nine minutes. Schirra later described the reentry as “thrilling,” and the spacecraft “as stable as an airplane.”

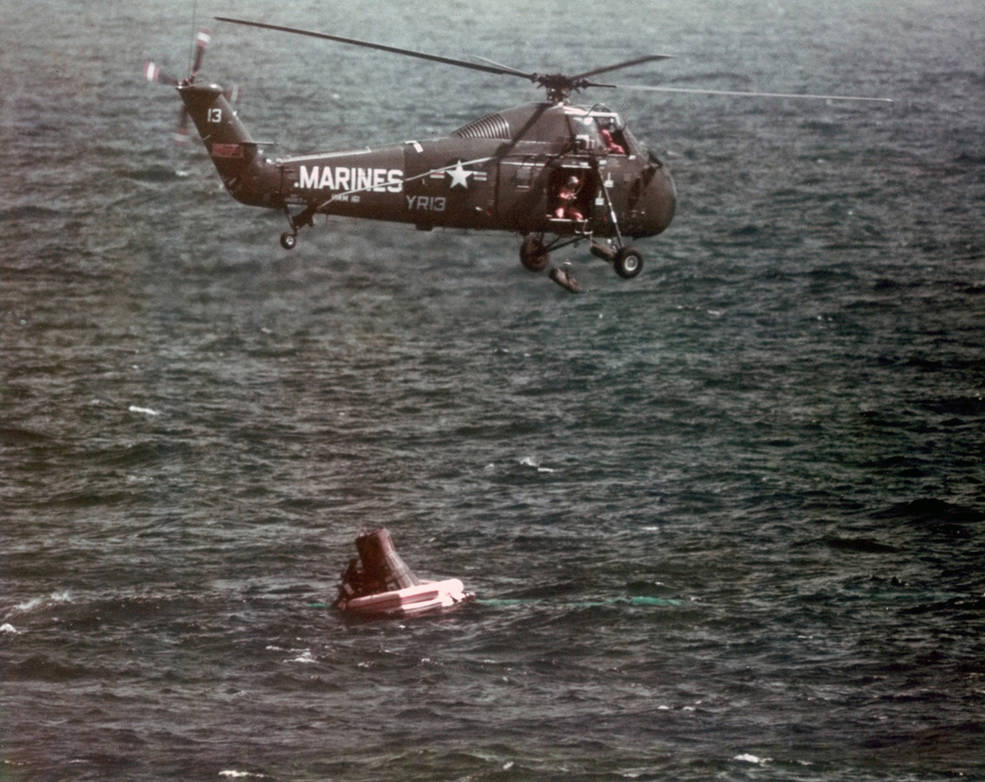

Left: Sigma 7 descending under its parachute just before splashdown, photographed from

the prime recovery ship the U.S.S. Kearsarge. Middle: Splashdown! Right: A rescue

helicopter from the Kearsarge begins the recovery operations.

At a distance of 150 miles, Kearsarge’s radar picked up the descending capsule, and because of the accuracy of its trajectory toward splashdown, sailors on the ship could observe its descent. At 40,000 feet altitude, the capsule’s drogue parachute deployed to slow and stabilize it, followed by the main parachute at 10,000 feet. As sailors and NASA officials watched from the carrier, Sigma 7 splashed down, an event Schirra later described as a “plop.” The pinpoint-accurate landing took place four and a half miles from the Kearsarge. Schirra’s six-orbit mission had lasted nine hours, 13 minutes, and 10 seconds, at the time the longest American crewed mission.

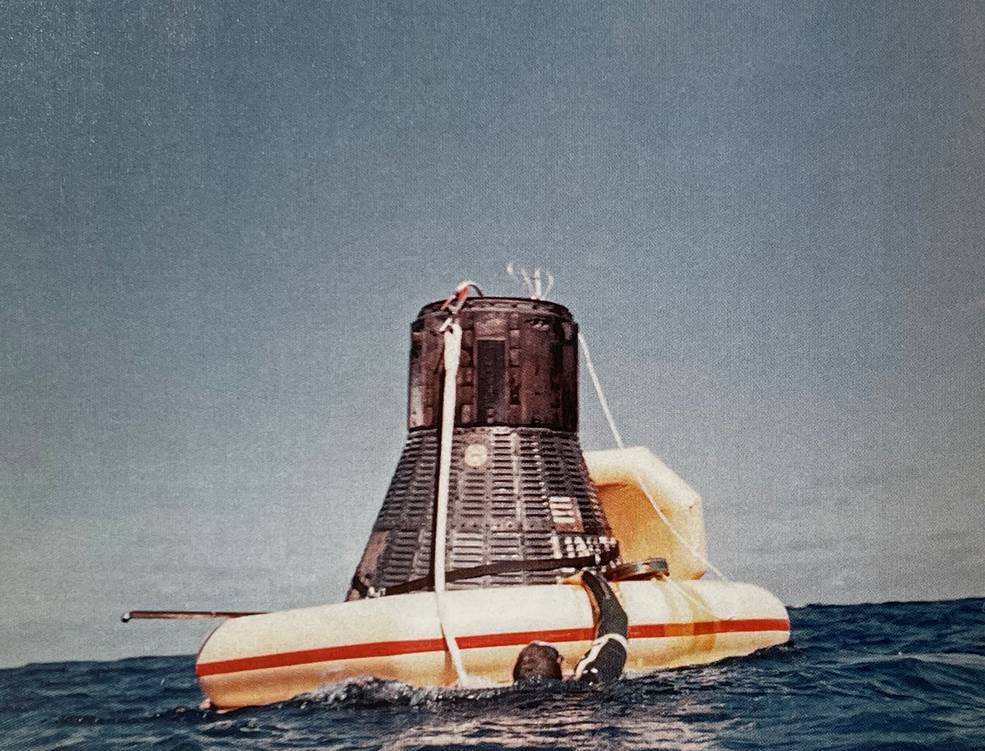

Left: Sigma 7 with its flotation collar attached, photographed by one of the Navy

frogmen in the water. Middle: A whale boat from the U.S.S. Kearsarge approaches

Sigma 7 to attach a tow line. Right: The U.S.S. Kearsarge approaches Sigma 7,

with astronaut Walter M. Schirra still inside, to hoist it aboard.

U.S. Navy frogmen jumped into the water from helicopters to attach a flotation collar around the spacecraft. Schirra elected to stay inside his spacecraft for the recovery, so Kearsarge dispatched sailors aboard a whale boat to attach a tow line to the spacecraft. Meanwhile, the carrier pulled up alongside the spacecraft and lifted it aboard.

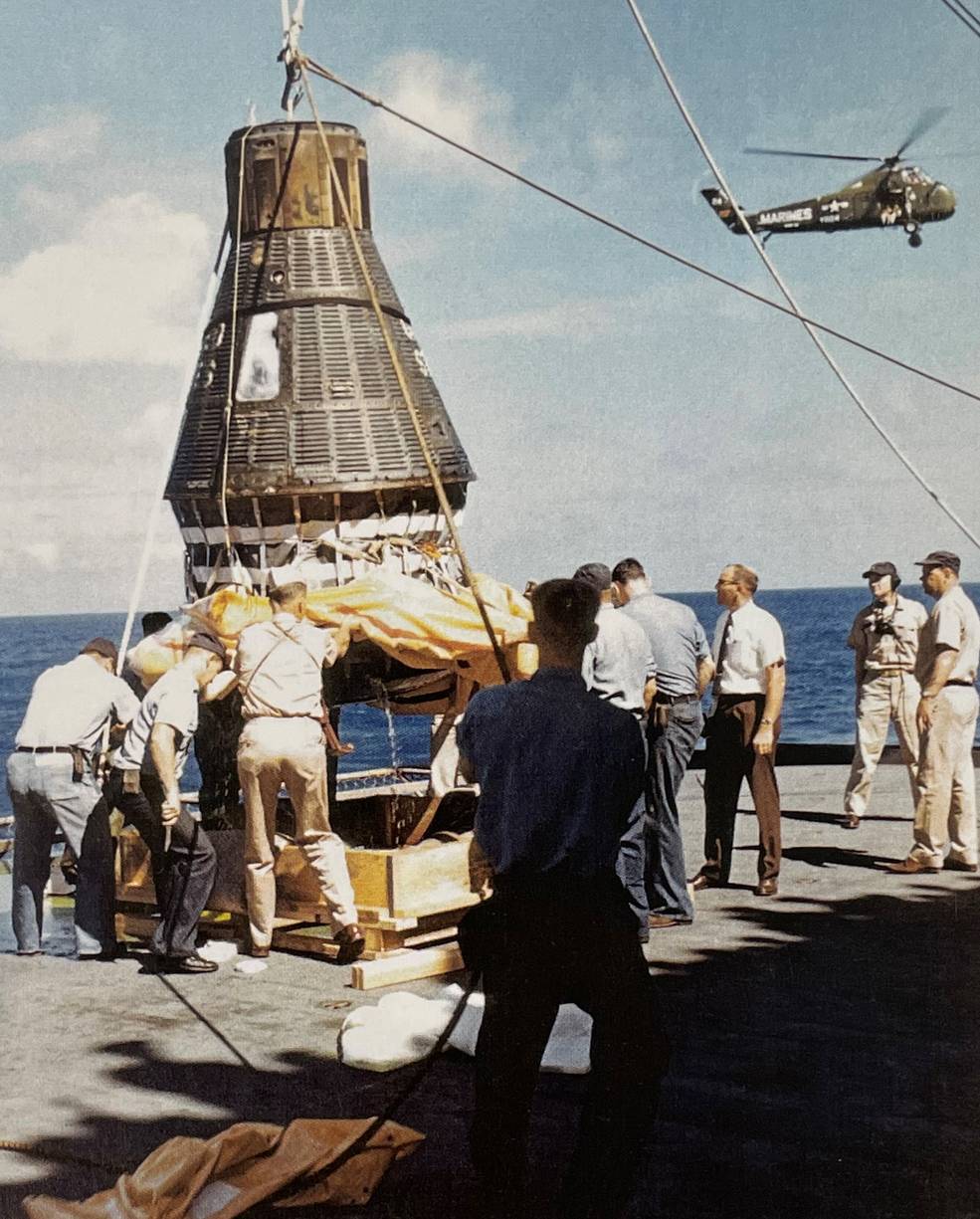

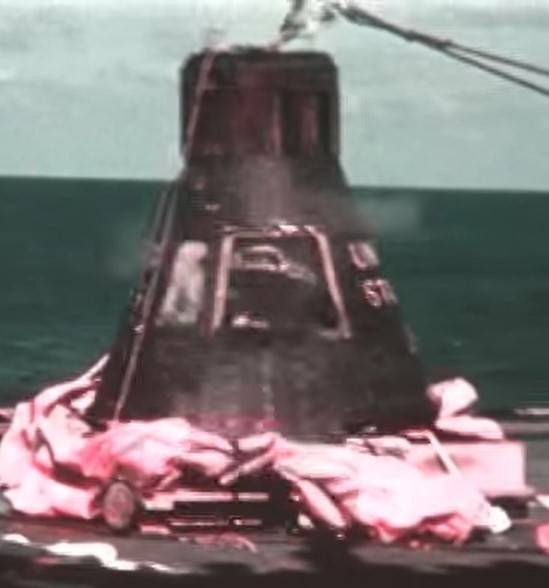

Left: Sailors lower Sigma 7, with astronaut Walter M. Schirra still aboard, onto the

U.S.S. Kearsarge. Middle: Sigma 7 the moment after Schirra blew the side hatch.

Right: Schirra emerges from the capsule.

Just 42 minutes after splashdown, Sigma 7 rested on the carrier and Schirra blew the spacecraft’s side hatch. Navy and NASA personnel assisted him out of the tight confines of the Mercury capsule, and Schirra stepped onto the deck of the carrier. He briefly examined the condition of his spacecraft. After shaking hands with the ship’s captain and waving to the assembled sailors, Schirra went below decks to the ship’s sick bay for his postflight medical examination.

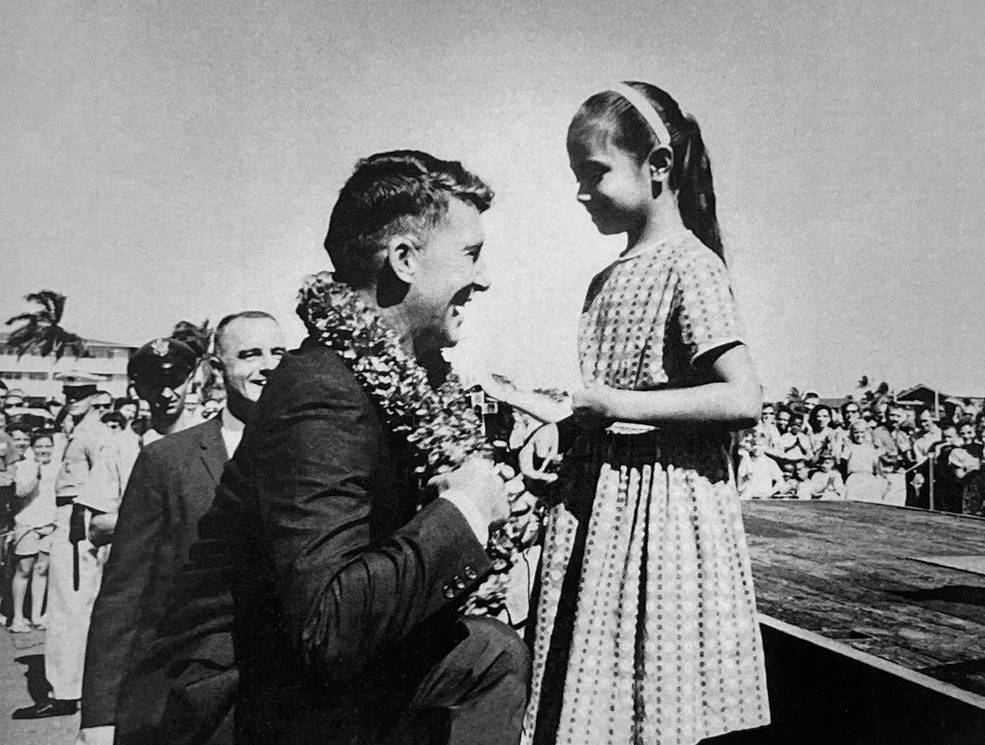

Left: Astronaut Walter M. Schirra takes a congratulatory telephone call from President

John F. Kennedy aboard the prime recovery ship U.S.S. Kearsarge. Middle: Aboard

Kearsarge, Schirra begins his post-mission debriefs with NASA managers and fellow

astronauts. Right: In Honolulu, Schirra receives a traditional lei

from eight-year old Kalani Flood.

Shortly after arriving on the carrier, Schirra took congratulatory phone calls from President Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, and his wife Jo and their two children, Marty and Suzanne. Flight surgeons thoroughly examined Schirra and declared him to be fit. They only found two minor issues, temporary orthostatic hypotension, or tendency to faint upon standing – likely caused by a combination of dehydration and being in the capsule for many hours – and a bruise on his knuckle caused by the plunger mechanism to blow the hatch once the capsule arrived on the carrier. The orthostatic hypotension had cleared by the following morning. Schirra spent the next three days aboard the Kearsarge as it steamed toward Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, with a brief stop at Midway Island to offload the Sigma 7 spacecraft for its journey back to Cape Canaveral. During that time, he held debriefs with NASA managers and five of his fellow astronauts who had arrived aboard the carrier by aircraft. On Oct. 6, a crowd of 2,000 dignitaries and well-wishers welcomed Schirra at Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu, where eight-year old Kalani Flood presented him with a traditional lei of red carnations.

Left: Astronaut Walter M. Schirra, left, shakes hands with child television actor Jay North at

the start of the parade in Houston, as his wife Jo looks on. Middle: Schirra and

his family in the motorcade through the streets of Houston. Right: Schirra

and family arrive on the Rice University campus.

From Hawaii, Schirra traveled non-stop to Houston, arriving at Houston’s International Airport, now William P. Hobby Airport, at 1 a.m. on Oct. 7. Schirra reunited with his wife Jo and their two children. Despite the hour, Texas Governor M. Price Daniel, Houston Mayor Lewis W. Cutrer, and NASA officials met him on the tarmac. The Schirras left for their new home near the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center, southeast of Houston, for some much-needed rest. Given Schirra’s busy training schedule, this was his first night in the house. Later that day, the Schirras found themselves at the Farnsworth and Chambers Building, MSC’s interim headquarters in southeast Houston. Child actor Jay North of the television series “Dennis the Menace,” in Houston on a promotional tour, dressed in a spacesuit for the occasion and posed for photographs with the Schirras. An estimated 300,000 people lined the motorcade route from MSC Headquarters through the streets of Houston to Rice University, where NASA had scheduled the postflight press conference.

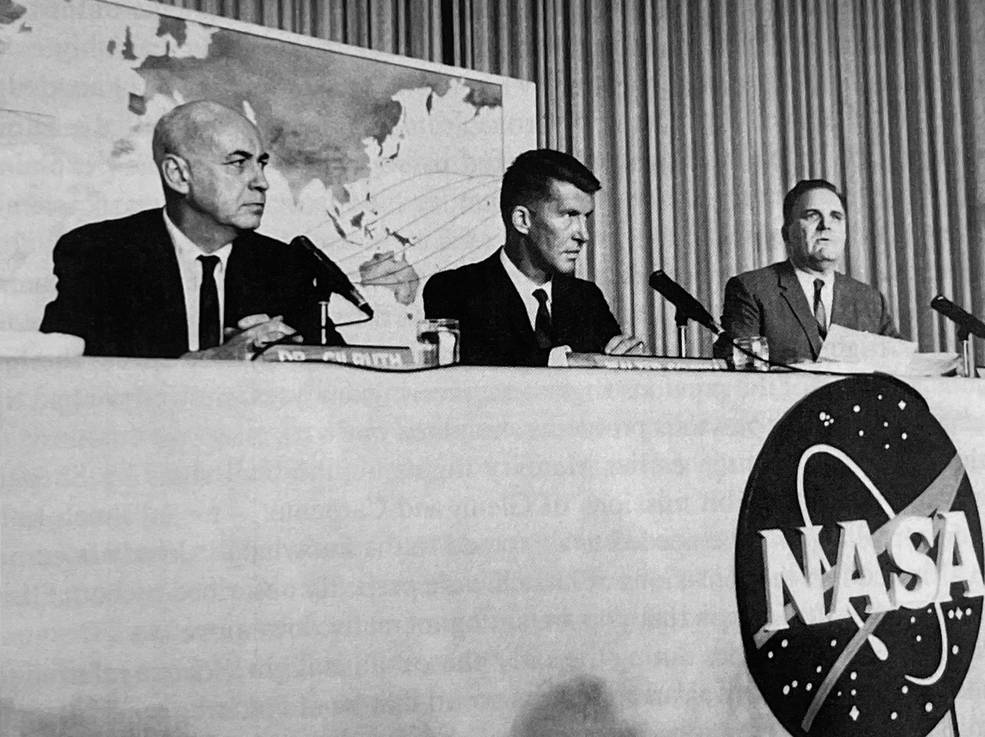

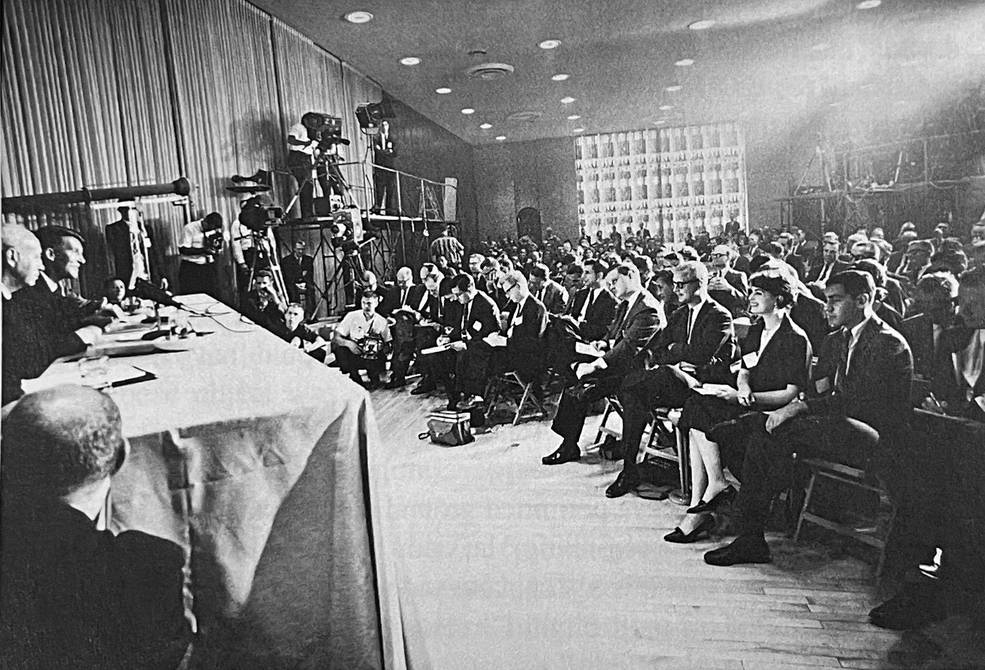

Left: Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center

in Houston, Robert R. Gilruth, left, astronaut Walter M. Schirra, and NASA

Administrator James E. Webb during the postflight press conference at Rice

University in Houston. Right: More than 300 reporters attend the

postflight press conference.

NASA Administrator James E. Webb and MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth joined Schirra on the stage. Webb led off the press conference and introduced Gilruth and Schirra to the 300 assembled reporters. Gilruth pointed out that America’s future in space depended on the success of missions like Schirra’s that called upon the collective work of thousands of individuals. Schirra first introduced his family and the five fellow astronauts in the room. He then described his mission, at one point calling it a “textbook flight.” Schirra highlighted the positive nature of his communications with MCC and with the ground stations around the world. He saw no impediment for the next Mercury mission to last a full day. Two days later, Schirra flew back to Cape Canaveral to review the data recorded during the mission with engineers and scientists.

Left: Astronaut Walter M. Schirra, left, with his wife Jo and their two children

ride in a convertible during the hometown parade in Oradell, New Jersey.

Right: Schirra, middle, his wife Jo and their two children meet with

President John F. Kennedy at the White House.

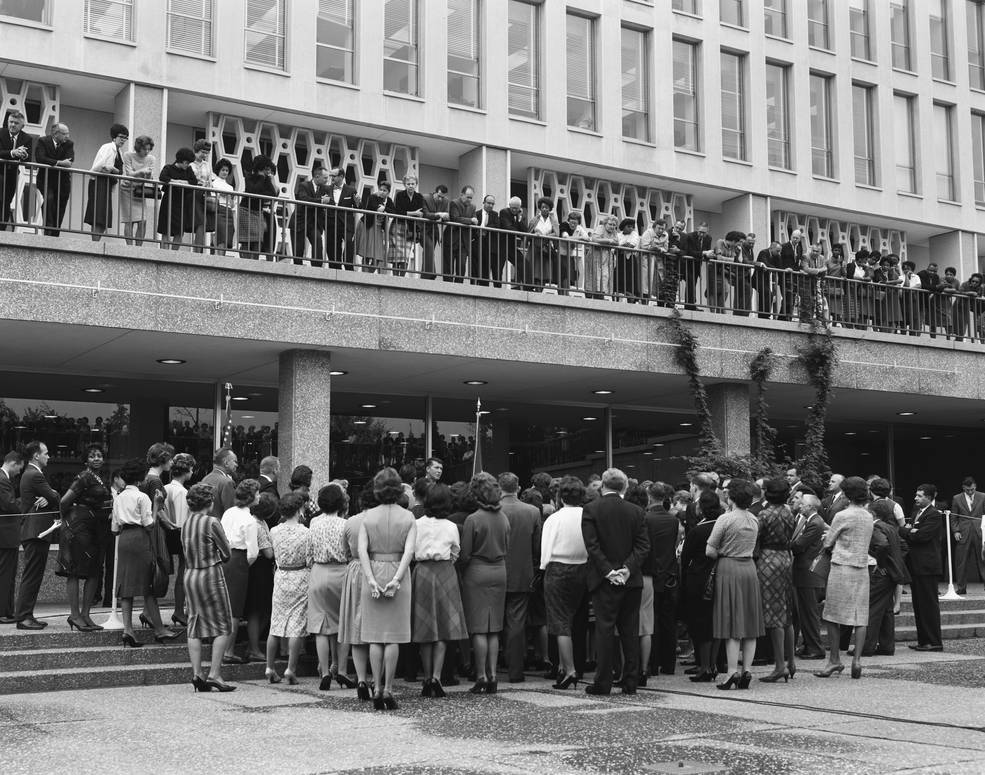

Left: Astronaut Walter M. Schirra, in the middle of the crowd, gives a speech to

employees outside NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Right: At the Pentagon,

Schirra, middle, receives his Navy astronaut wings from Secretary of the Navy

Frederick H. Korth as his wife Jo looks on.

On Oct. 14, the Schirras traveled to New Jersey for welcome home celebrations in Schirra’s birthplace of Hackensack and his hometown of Oradell. The next day, a motorcade took them through the streets of the towns, with an estimated 40,000 well-wishers lining the route. At the Oradell football stadium, where 8,000 people had gathered, NASA Administrator Webb presented Schirra with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal for successfully accomplishing the Mercury-Atlas 8 mission and read a message of congratulations from President Kennedy. That evening, the Schirras flew to Washington, D.C., where the next morning, President Kennedy hosted them at the White House. The informal ceremony took place just hours after aides had first shown the President photographic evidence of the buildup of Soviet missiles in Cuba. After leaving the White House, Schirra gave a short speech to employees outside the NASA Headquarters building and signed autographs. Later in the day, Schirra now dressed in his full-dress uniform, received his Navy astronaut wings from Secretary of the Navy Frederick H. Korth. At the end of a long day, the Schirras flew home to Houston. The next morning, Schirra left for Cape Canaveral to finish his debriefings and write his post mission report.

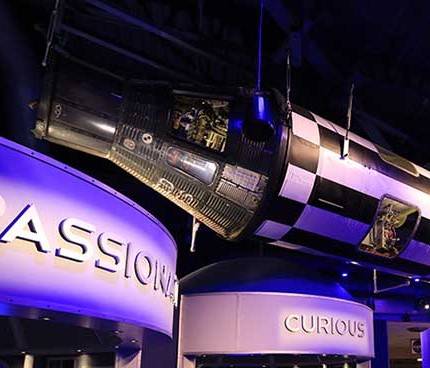

Left: Ground crews unload Sigma 7 from the U.S.S. Kearsarge on Midway Island.

Middle: Sigma 7 arrives back at Hangar S in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Right: Sigma 7 on display at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida.

Schirra’s Sigma 7 spacecraft took a different route after splashdown back to Cape Canaveral. Workers offloaded the Mercury capsule from the Kearsarge at Midway Island and placed it aboard a C-130 Hercules cargo aircraft for the flight back to Cape Canaveral. Workers in Hangar S inspected the spacecraft to assess any effects from its nine-hour orbital flight. From there, ground crews trucked Sigma 7 to its manufacturing site, the McDonnell Aircraft Corp. plant in St. Louis, where engineers gave it a more thorough inspection. After spending some time on display at the McDonnell plant, Sigma 7 went on a limited world tour until Sept. 20, 1967, when NASA transferred ownership to the Smithsonian Institution. For the next 27 years, Sigma 7 remained on exhibit at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, before transferring to the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in Titusville, Florida, in March 1990. When that facility closed in November 2015, Sigma 7 relocated to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida, where it remains on display in the Heroes and Legends Hall, oddly mated to a Redstone rocket.