On Jan. 27, 1967, with the planned launch of the first Apollo mission to carry a crew just 25 days away, Apollo 1 astronauts Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, Edward H. White, and Roger B. Chaffee were conducting a key test with their spacecraft on the launch pad. The test involved a mock countdown with the astronauts wearing spacesuits inside their capsule, sealed and pressurized with oxygen. At the time of simulated liftoff, the plan called for the spacecraft to switch to its own internal power source. The crew also planned an emergency escape drill from the spacecraft at the test’s conclusion. During the test, a flash fire swept through their spacecraft so quickly they had no time to open the hatches. The astronauts perished from toxic gases in the craft’s environmental control system.

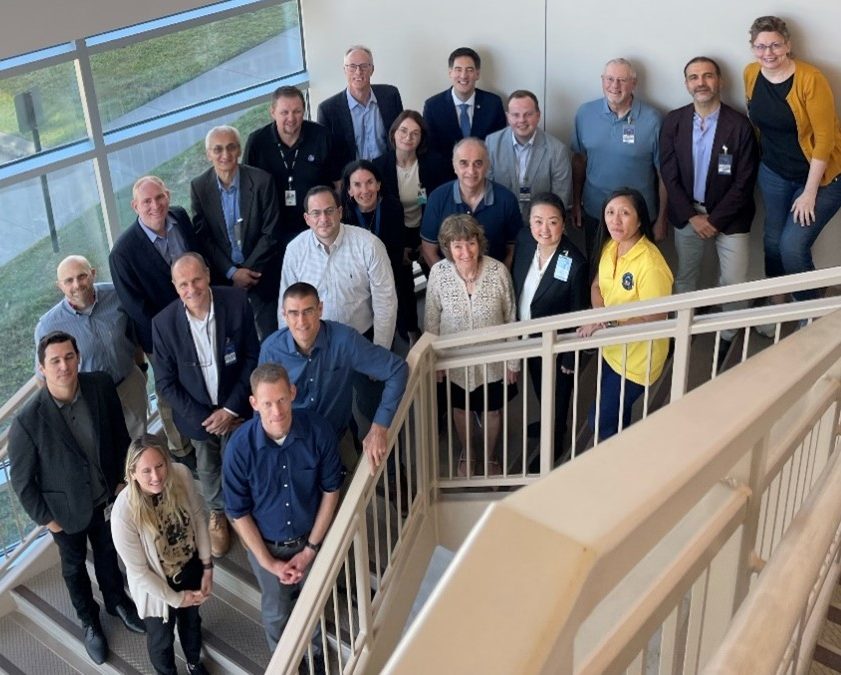

Left: Apollo 1 astronauts Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, left, Edward H. White, and

Roger B. Chaffee pose for photographers during a media event at Launch

Complex 34. Right: The mission patch for the Apollo 1 crew.

In January 1967, at the NASA-operated Launch Complex 34 (LC-34) at the Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, preflight processing of the Apollo 1 spacecraft and its Saturn IB rocket continued in preparation for the Feb. 21 planned liftoff. On Jan. 6, the spacecraft arrived at the pad where workers installed it atop the rocket and integrated it with the launch vehicle. On Jan. 25, the Apollo 1 backup crew of Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham conducted a mock countdown, with the launch pad’s service structure providing power to the spacecraft. The hatch to the capsule remained opened during the test that was plagued by a series of glitches, both with ground equipment and with the vehicle. Although the test took several hours longer than planned, it met its major objectives. On Jan. 27, Grissom, White, and Chaffee were scheduled to perform a test formally called the “Space Vehicle Plugs-Out Integrated Test” and simply referred to as the “plugs-out” test. The principal difference from the earlier “plugs-in” test performed by the backup crew was that when the countdown reached the simulated liftoff time, the spacecraft would switch from ground power sources to a simulated fuel cell power source, in a rehearsal of the actual launch. The crew requested that a spacecraft emergency egress drill be added to the end of the test.

Left: Apollo 1 astronauts Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, left, and Roger B. Chaffee arrive at

Launch Complex 34 in preparation for the plugs out test on Jan. 27, 1967.

Right: Donald K. “Deke” Slayton, Chief of Flight Crew Operations, left,

leads Apollo 1 astronaut Edward H. White after arriving at

Launch Complex 34.

The evening before the plugs-out test, Schirra met with Grissom and Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager Joseph F. Shea in the crew quarters at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Not satisfied with the number of glitches during the plugs-in test, Schirra told Grissom that if things didn’t feel right during the plugs-out test, he should end it. The morning of the test, Grissom, White, and Chaffee had breakfast with Shea and Chief of Flight Crew Operations Donald K. “Deke” Slayton. Grissom asked Shea to join them in the capsule for the day’s test to experience the glitches firsthand. Shea was willing, but after technicians explained they couldn’t hook up a fourth communications link in the capsule, he dropped the idea and flew home to Houston. At LC-34, engineers powered up the spacecraft just before 8 a.m. and verified that all its systems were in readiness for the day’s test. In crew quarters, following breakfast the three astronauts donned their spacesuits at 10 a.m. and began breathing pure oxygen from portable packs. Slayton accompanied Grissom, White, and Chaffee to LC-34 in the astronaut transfer van. First, Grissom and Chaffee rode the elevator to level A8, about 218 feet above the ground, and crossed the crew access arm that led to the White Room that provided access to the Apollo Command Module (CM), enclosed in the pad’s service structure. At 1 p.m., assisted by the White Room technicians, Grissom entered the capsule and took his position in the left hand couch, followed by Chaffee who took the right hand couch. White and Slayton followed, and White took the center couch while Slayton left to observe the test. A team of technicians remained at level A8 of the service platform outside the White Room for the duration of the test that was expected to take about two hours.

Left: Launch Complex 34 (LC-34) at Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida – the Launch Control Center, also known as the blockhouse, is the domed structure in the foreground. Middle: Interior of the blockhouse at LC-34. Right: View of the Acceptance Checkout Equipment room in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Several teams monitored the Jan. 27 test via voice, telemetry, and closed-circuit television. At the Launch Control Center, also known as the blockhouse, 1,200 feet from the rocket at LC-34, a team of engineers monitored the progress of the test, as they would on launch day, with primary responsibility for the launch vehicle. Astronaut Stuart A. Roosa served as the spacecraft communicator who talked directly with the crew, and Slayton sat with him to observe the test after getting the crew in the CM. Five miles away in the Acceptance Checkout Equipment (ACE) control room in KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building, Clarence A. “Skip” Chauvin served as the NASA spacecraft test conductor, who communicated directly with the crew along with Roosa. In the Mission Control Center at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, teams of engineers monitored the test, led by the three flight directors assigned to Apollo 1 – Christopher C. Kraft, Eugene F. Kranz, and John M. Hodge.

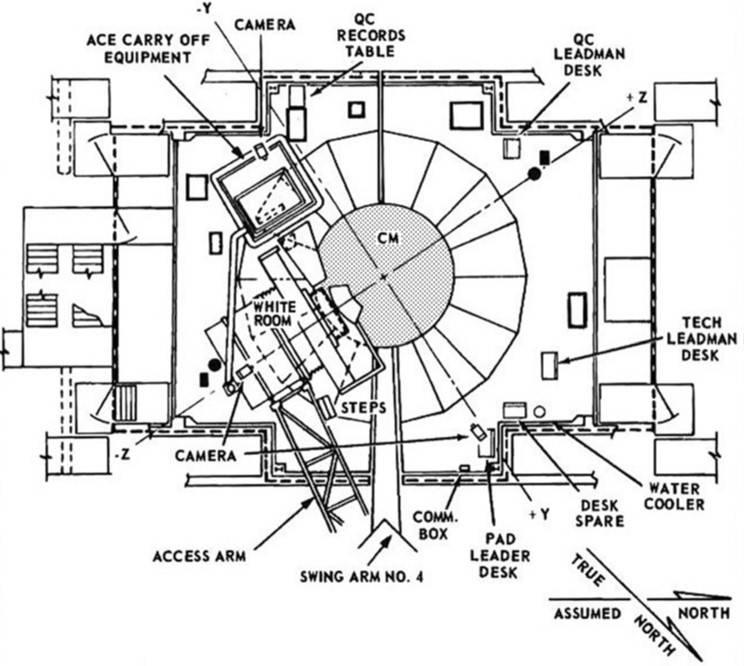

Left: Apollo 1 astronaut Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom leads fellow crew member Roger

B. Chaffee across the Crew Access Arm to the White Room to enter the Apollo

Command Module (CM) – third crewmember Edward H. White followed shortly

after. Right: Schematic diagram of level A8 at Launch Complex 34,

showing the relative locations of the CM, the White Room, the Crew

Access Arm, and the Service Structure’s adjustable platform.

Shortly after entering the spacecraft and connecting to its environmental control system, Grissom reported a sour smelling odor. The test was interrupted at 1:20 p.m. while engineers arrived at the pad to sample the air. Finding no anomalous readings, and the odor having dissipated, the test resumed at 2:42 p.m. The astronauts and pad teams closed and sealed the spacecraft’s three hatches and pressurized the capsule with pure oxygen to 16 pounds per square inch (psi), slightly higher than the outside air. For the next few hours, communications issues plagued the test. An unidentified microphone left in the open position contributed so much static that the crew and the control centers in the blockhouse and the ACE room had difficulty understanding each other. Controllers halted the test at 5:40 p.m. to let the astronauts reconfigure communications equipment in the spacecraft in an attempt to solve the problem. At 6 p.m., Chauvin instructed Grissom to proceed with a planned simulated hot fire of the CM’s reaction control system thrusters, which he completed successfully despite the ongoing communications issues. At one point after the thruster test, chatter from Miami’s air traffic control intruded on the communications link with the spacecraft. Chauvin then realized that Grissom’s hardline communications link would be lost when the spacecraft’s connections with the launch pad were pulled at the simulated liftoff time. This required reconfiguring all three astronauts’ communications systems, further frustrating an already irritated Grissom. Communications checks with each astronaut followed, but the ground still had difficulty hearing them clearly. At 6:30 p.m., the count had reached T minus 10 minutes and was holding pending resolution of the ongoing communications issues. Grissom complained, “How are we gonna get to the Moon if we can’t talk between three buildings?” White chimed in that “they [the ground] can’t hear a thing you’re saying,” prompting Grissom’s exasperated “Jesus Christ!” followed by a repeat of his earlier question.

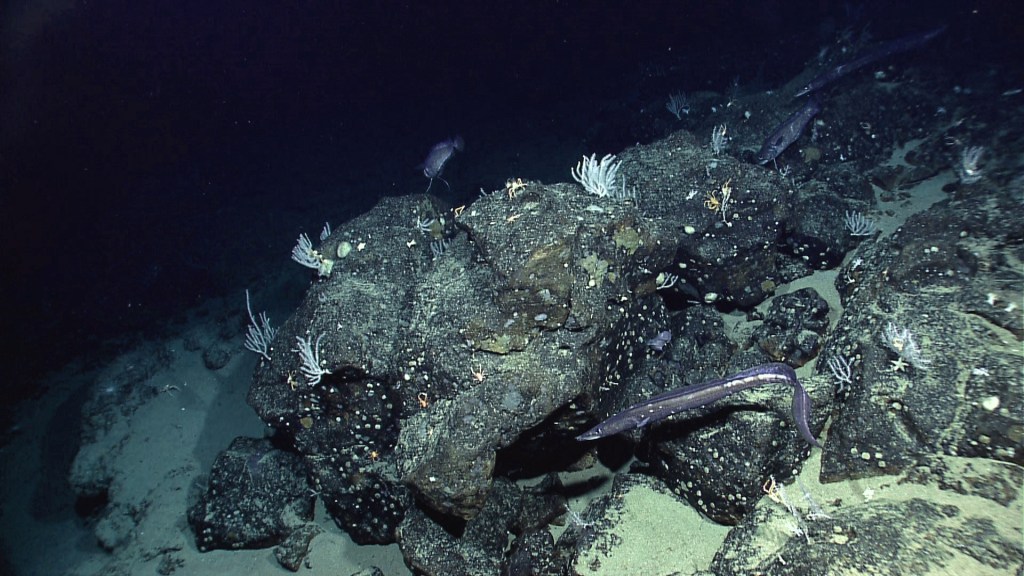

Left: View from the White Room of the charred remains of the Apollo 1

Command Module. Right: After the fire, outside the White Room, a

journalist examines two of the spacecraft’s hatches, the boost

protective cover hatch at left and the internal spacecraft

hatch (positioned upside down).

At 6:30:55 p.m., engineers monitoring telemetry from the spacecraft noted a voltage spike in one of the spacecraft’s electrical busses and other anomalous electrical signals. Ten seconds later, one of the astronauts, possibly Grissom, yelled, “Fire!” followed in two seconds by Chaffee yelling “Hey! We’ve got a fire in the cockpit!” Seven seconds later, as White tried in vain to open the inward-opening inner spacecraft hatch, Chaffee yelled, “We have a bad fire!! We’re burning up!” followed by a scream. Then radio transmissions from the spacecraft ceased, 18 seconds after the first report of the fire. In the confusion that followed, Chauvin and Roosa continued to call the crew, hoping they had a means to escape the conflagration.

Left: On level A8 of the service structure, an external view of the

Apollo 1 Command Module, showing the soot deposited from the fire.

Right: A view of level A8 of the service structure

showing fire damage.

Shocked observers watching the closed-circuit television feed from the camera trained on the spacecraft’s hatch noticed flames shooting from left to right across the window, indicating the fire started on Grissom’s side of the capsule. They also observed crew movements that looked like attempts to open the inner hatch. Within seconds the entire window turned white as the spacecraft filled with flames. The pressure built up inside the capsule to an estimated 30 psi, causing the CM pressure vessel to crack, sending flames and smoke onto level A8 of the service structure and causing concern that the flames would reach the launch escape system tower filled with highly explosive solid fuel. Three seconds later, communications from the spacecraft ceased. Upon first report of the fire, technicians rushed to the White Room to try to rescue the astronauts, but the smoke, heat, and flames frustrated their efforts. Taking turns on the access arm for fresh air, the workers first removed the outer boost protective cover hatch that was only partially installed, then opened the middle spacecraft hatch, and finally the inward opening inner hatch. Their efforts took about five minutes, and many suffered smoke inhalation and burns in their futile attempt to save the astronauts who by this time had already perished. NASA flight surgeons G. Fred Kelly and Alan C. Harter arrived shortly after the pad crew opened the hatch and confirmed that the astronauts were dead. Slayton and Roosa arrived from the blockhouse soon after along with firemen who extinguished any remaining fires. Initial attempts to remove the crew proved unsuccessful because the intense heat had fused their spacesuits with nylon netting and other materials in the spacecraft. Firemen finally removed the astronauts at 1 a.m. the morning of Jan. 28 and took them to the Biomedical Operations Support Unit, an Air Force medical clinic about a mile from the pad that now served as a temporary morgue.

Ad astra Gus, Ed, and Roger.

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center