Selected as the Prime Recovery Ship (PRS) for Apollo 12 on Aug. 17, 1969, USS Hornet (CVS-12) steamed out of her home port of Long Beach, California, on Oct. 27 and arrived at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, four days later. Hornet served as the PRS for Apollo 11 in July 1969 and her skipper Capt. Carl J. Seiberlich and crew put that experience to good use. Reflecting both the previous recovery activities and the emphasis on the safe retrieval of the astronauts, Capt. Seiberlich chose Three More Like Before as the motto for the Apollo 12 operation. The US Navy frogmen for Apollo 12 comprised a new team from Underwater Demolition Team-13 (UDT-13), with Ernest L. “Ernie” Jahncke serving as the decontamination officer.

USS Hornet (CVS-12), the Prime Recovery Ship for Apollo 12.

Credits: US Navy.

While in dock at Pearl Harbor, workers loaded two Mobile Quarantine Facilities (MQFs), highly modified Airstream trailers, aboard Hornet and other equipment required for the recovery operation. The MQFs, one prime and one backup, served as the initial quarantine location for the astronauts after splashdown until they reached the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston. The major change in the recovery protocols involved the astronauts no longer having to wear the hot and bulky Biological Isolation Garments (BIGs) worn by the Apollo 11 crew – managers decided that clean overalls and respirators provided adequate protection against back-contamination since scientists found no evidence of any pathogenic lunar microorganisms in the Apollo 11 samples. On Nov. 10, Hornet slipped her moorings at Pearl Harbor and arrived at the Apollo 12 target location in the South Pacific 375 miles east of Pago Pago, American Samoa, on splashdown day, Nov. 24.

Left: The two MQFs below decks on the USS Hornet prior to recovery operations.

Right: Recovery helicopter on the USS Hornet with the operation’s motto Three More Like Before.

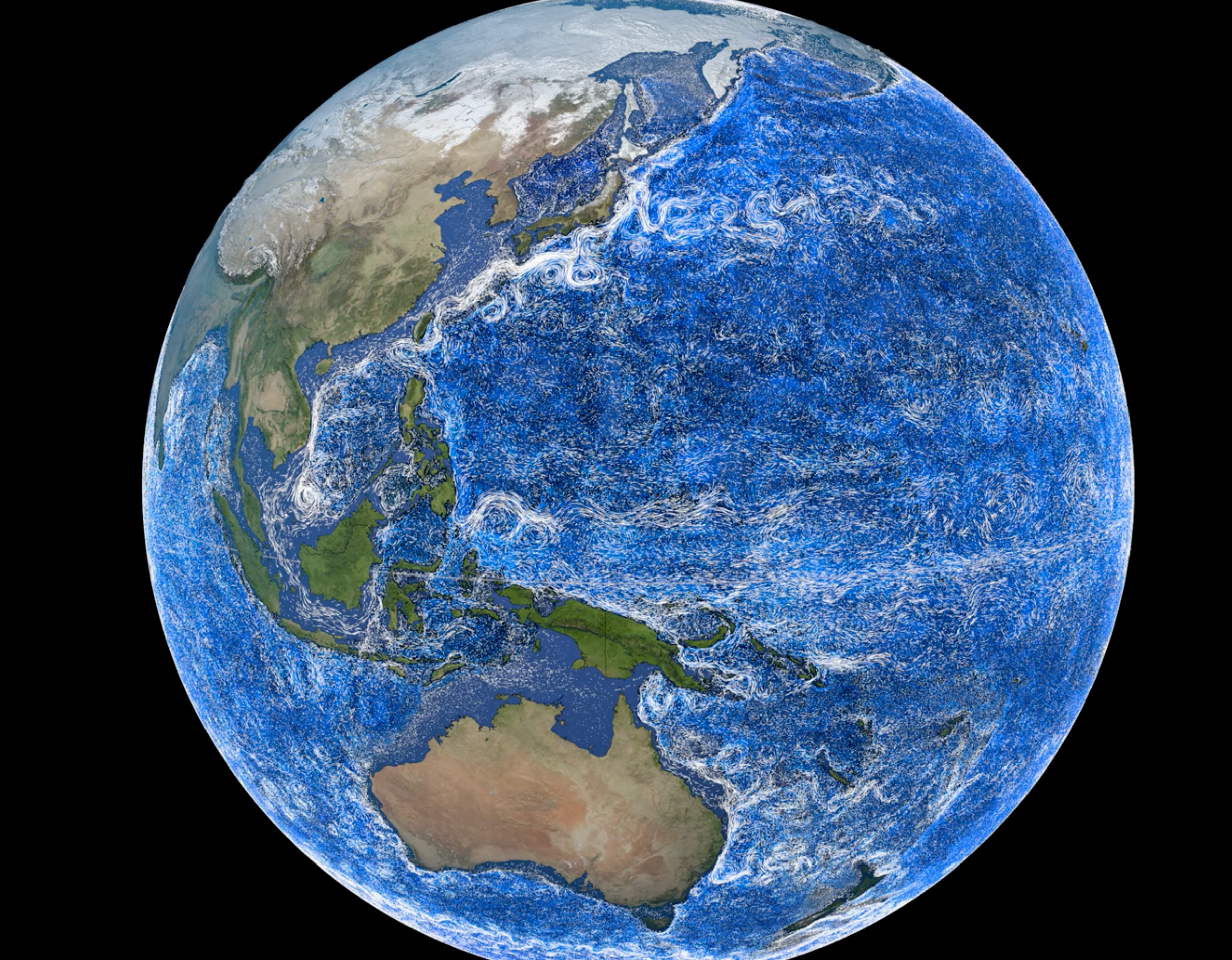

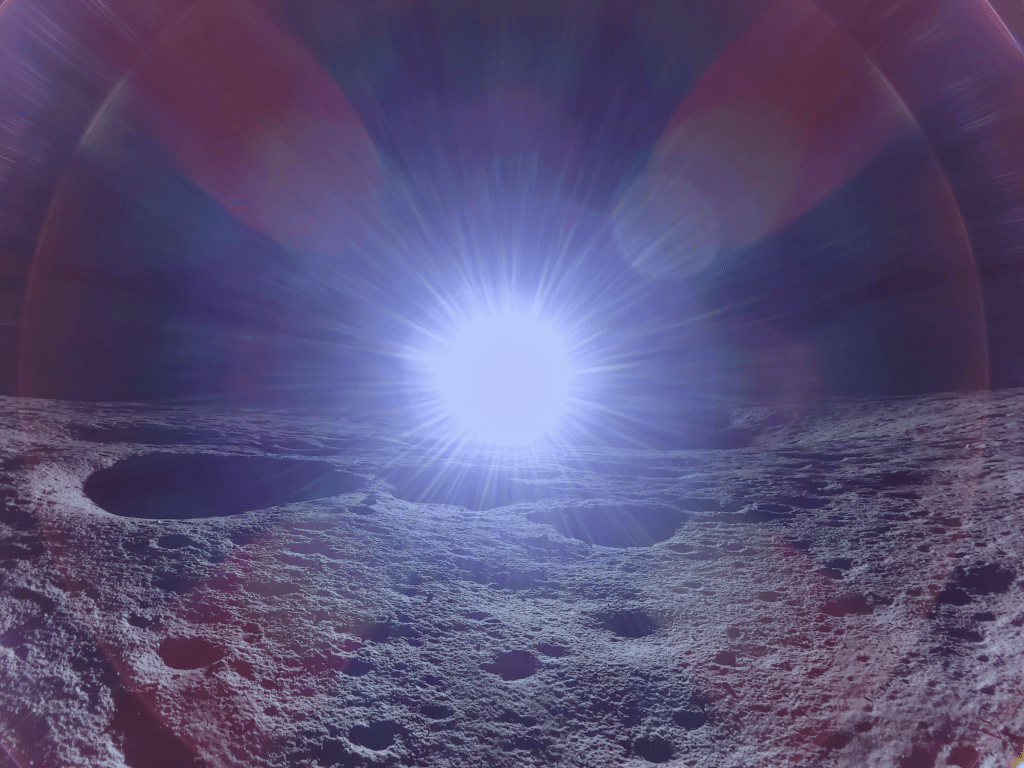

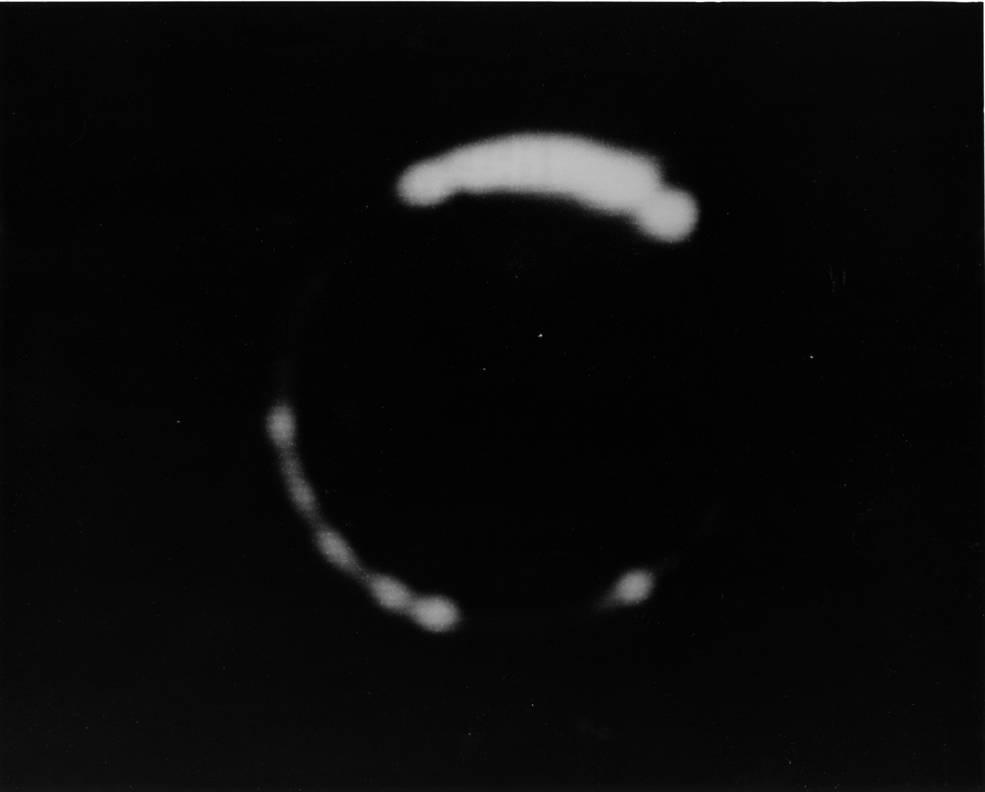

Aboard the Apollo 12 Command Module (CM) Yankee Clipper, the crew of Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean awoke for their last day in space, now only 72,000 miles from Earth and rapidly accelerating. The first order of business for the day consisted of preparing for a minor course correction, a five-second retrograde burn of the Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters to refine the spacecraft’s entry corridor into the atmosphere. And orbital mechanics had a show in store for the astronauts – their trajectory passed through the Earth’s shadow, treating them to a total solar eclipse. From their perspective, the Earth appeared about 15 times larger than the Sun. With Apollo 12 about 30,000 miles from Earth and travelling at 7,500 miles per hour, Gordon radioed Mission Control, “We’re getting a spectacular view at eclipse,” and Bean added that it was a “fantastic sight.” Conrad reported on the rapidly changing scenery, with the Sun illuminating the Earth’s atmosphere in a 360-degree ring with ever-changing colors while the planet remained pitch black. In the darkness, they could see flashes of lightning in thunderstorms appearing as fireflies. Unfortunately, they had no color film left for still photography, but used the 16 mm film camera to capture color images of the eclipse. As their eyes adapted to the dark portion of the Earth, they made out landmasses such as India and even city lights. In the center of the Earth’s dark disc they reported seeing a large bright circle that turned out to be the glint of the full Moon reflecting off the Indian Ocean. During the course of the eclipse, Apollo 12 had travelled about 10,000 miles and its speed increased to 9,000 miles per hour. Interestingly, the robotic spacecraft Conrad and Bean visited on the Moon just a few days earlier, Surveyor 3, had taken the first photographs of a solar eclipse from the lunar surface on April 24, 1967.

Left: View of the solar eclipse seen from Apollo 12.

Right: View of a solar eclipse taken by Surveyor 3 from the lunar surface in 1967.

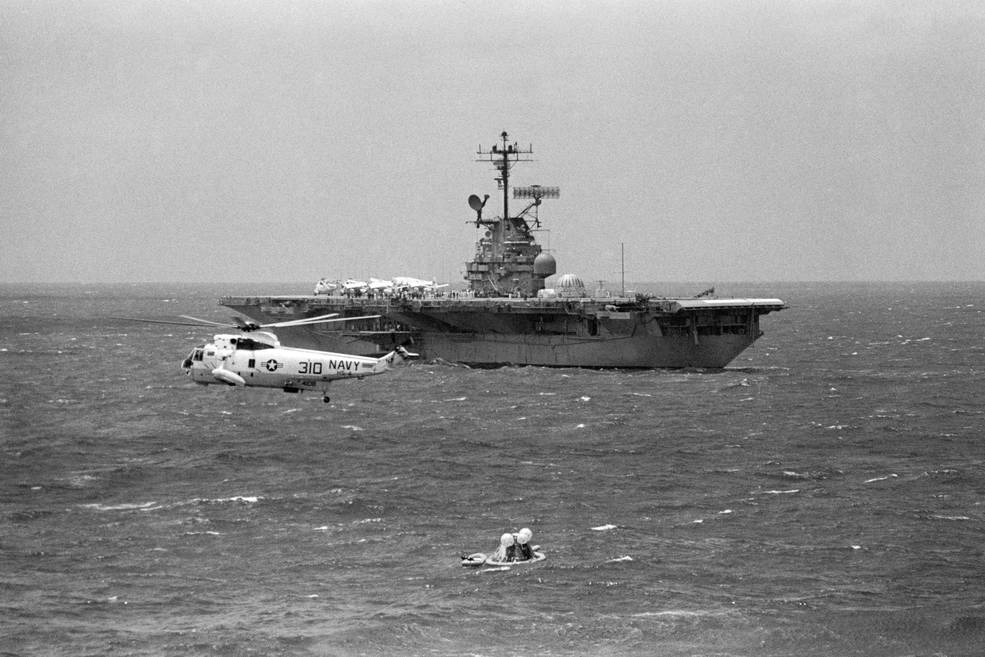

The excitement of the eclipse over, the astronauts prepared the cabin for reentry, activating and testing the CM’s thrusters. At an altitude of 4,245 miles, the CM separated from the Service Module and rotated to point its heatshield into the direction of flight. At an altitude of 400,000 feet, Yankee Clipper now travelling at 24,625 miles per hour encountered the first tendrils of Earth’s atmosphere. About four minutes of radio blackout followed as ionized gases created by the heat of reentry surrounded the spacecraft. Bean filmed the entry with a 16-mm camera mounted in Yankee Clipper’s right hand window. The spacecraft’s computer used the vehicle’s lift capability to execute a small skip maneuver to reduce heat loads on the heatshield. The astronauts experienced a peak deceleration of about 6 times the force of gravity. As Apollo 12 came out of the blackout, Hornet established radar contact with the spacecraft at a distance of 119 miles. At an altitude of about 24,000 feet, the spacecraft jettisoned its apex cover, followed by the deployment of the two drogue parachutes to slow and stabilize the capsule. At 10,000 feet, the three main 83-foot diameter orange and white parachutes deployed, with Conrad reporting, “Three gorgeous beautiful chutes.” Precisely 244 hours and 36 minutes after lifting off from Florida, Apollo 12 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean less than 4 miles from Hornet, bringing the second lunar landing mission to a successful conclusion. A NASA video of the Apollo 12 mission can be found here.

Left: Apollo 12 CM Yankee Clipper descending on its main parachutes moments before splashdown.

Right: View of Apollo 12 in the water with Hornet in the background and a recovery helicopter hovering.

Credits: US Navy.

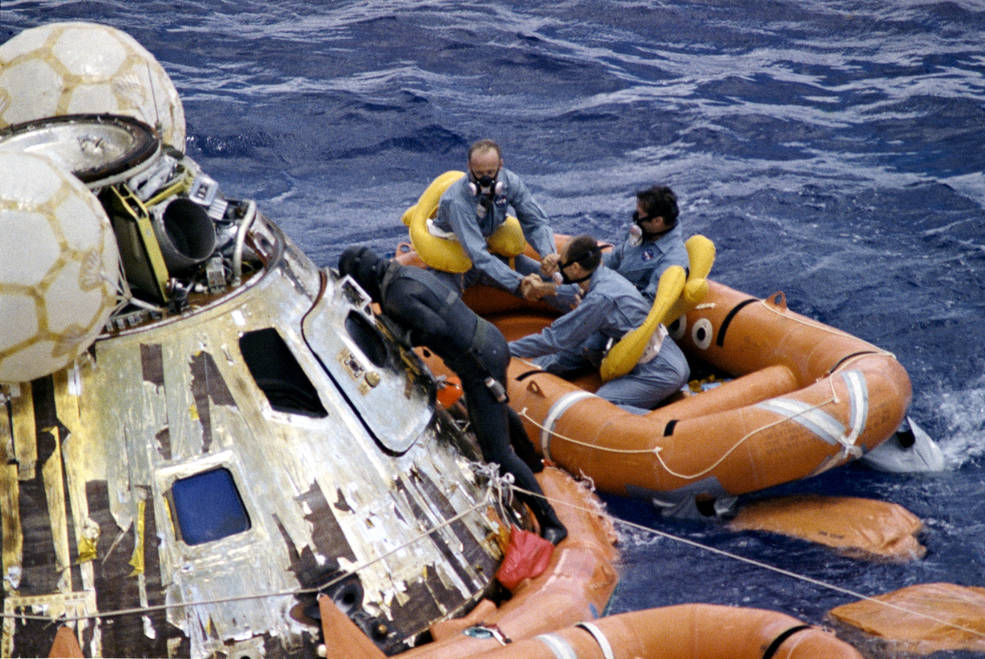

At the moment of splashdown, the CM hit a rising wave causing a harder than expected landing. The force of the impact displaced part of the heat shield and also dislodged the 16 mm film camera mounted in the window. The camera hit Bean in the head resulting in a gash and momentarily dazing him, causing him not to trip two circuit breakers to jettison the parachute lines. This resulted in the capsule assuming the apex down Stable 2 position in the water. Three self-inflating balloons righted the spacecraft into the Stable 1 upright orientation in less than five minutes. Five minutes later, a helicopter dropped the first three UDT swimmers into the water, tasked with securing a flotation collar and rafts to the spacecraft, tying a sea anchor to it for stability, and filming the recovery from the water. The process took about 10 minutes, while inside the capsule Conrad and Bean placed a bandage on Bean’s still bleeding forehead. Decontamination officer Jahncke next dropped into the water and once the crew opened the hatch, he handed them fresh flight suits and respirators. A few minutes later, the crew reopened the hatch, and first Conrad, then Gordon, and finally Bean climbed aboard one of the rafts where Jahncke used a disinfectant solution to decontaminate the astronauts and also the spacecraft. The recovery helicopter lowered a Billy Pugh net to haul the astronauts up from the raft, first Gordon, then Bean, and finally Conrad. Aboard the helicopter, NASA flight surgeon Dr. Clarence A. Jernigan gave each astronaut a brief physical examination during the brief flight back to Hornet, declaring all three of them healthy.

Left: View from the water of Bean assisted by Jahnke emerging from the capsule, with Gordon (left) and Conrad already aboard the raft. Right: View from the recovery helicopter of (left to right) Conrad, Bean, and Gordon aboard the raft as Jahncke closes the hatch and disinfects the capsule.

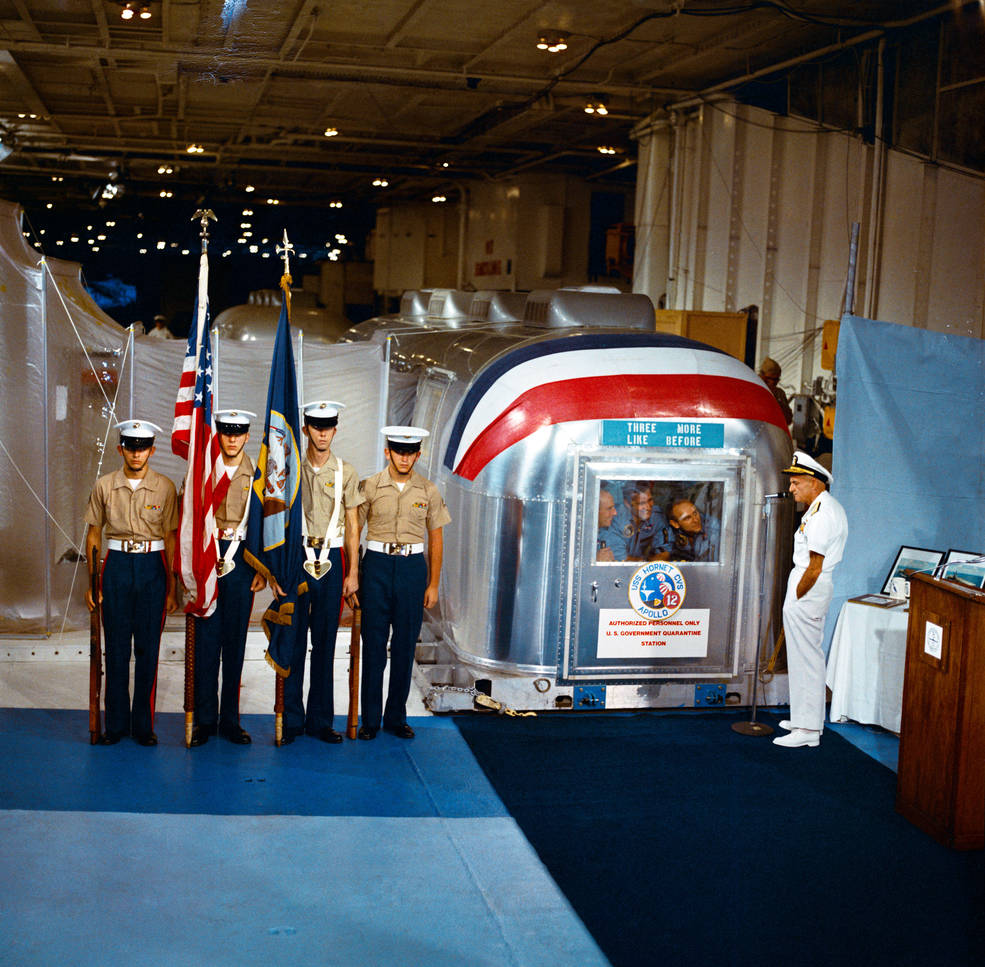

After landing on Hornet’s deck, sailors lowered the helicopter to the hangar deck, where Conrad, Gordon, and Bean, followed by Jernigan walked the few steps to the MQF where NASA engineer Brock R. “Randy” Stone awaited them. He sealed the door of the MQF exactly one hour after splashdown. The five men spent the next five days together in the MQF until they arrived at the LRL. The astronauts cleaned up and took congratulatory phone calls from President Richard M. Nixon, who field-promoted all three from US Navy Commanders to Captains, and from NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine. After the astronauts talked briefly with their families, Commander-in-Chief of Pacific Naval Forces Admiral John S. McCain formally welcomed them back to Earth, followed by brief speeches by Rear Admiral Donald C. Davis, Commander of Recovery Forces, and Capt. Seiberlich.

Left: Apollo 12 astronauts emerge from the recovery helicopter in Hornet’s hangar deck. Middle: Apollo 12 astronauts (front to back) Conrad, Gordon, and Bean walk from the helicopter to the MQF, followed by Dr. Jernigan. Right: Admiral McCain formally greets the Apollo 12 astronauts, peering out from inside the MQF – the reserve MQF is visible in the background.

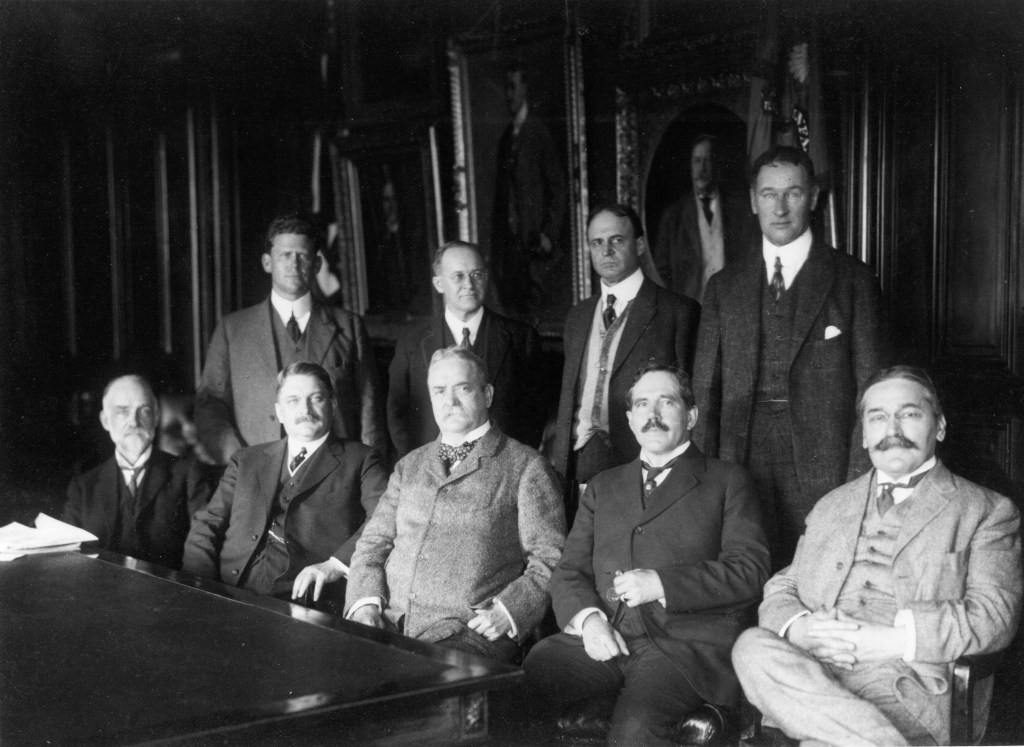

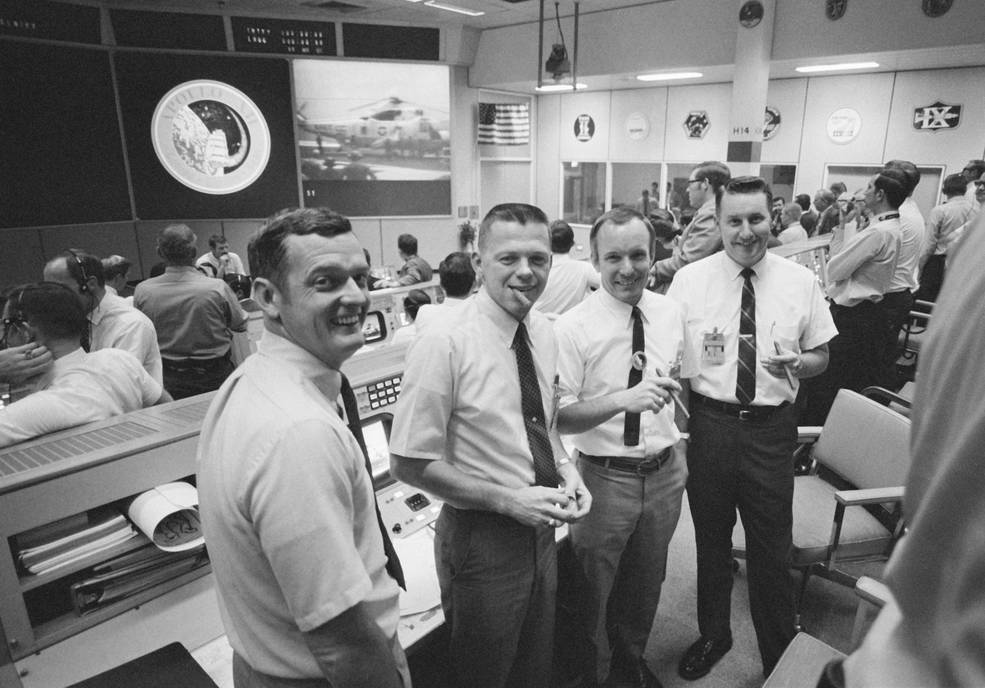

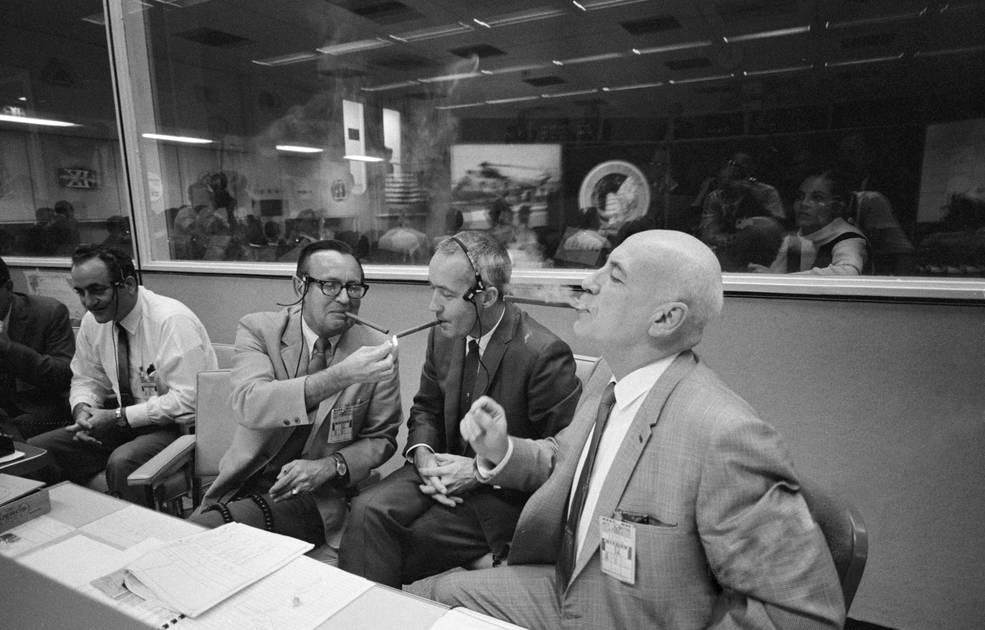

Mission Control in Houston was closely monitoring the splashdown and recovery activities, with most communications with the spacecraft being handled by Hornet’s recovery team. The room was rapidly filling to capacity as managers and engineers prepared for the celebration of a mission successfully accomplished. The four Apollo 12 Flight Directors, Glynn S. Lunney, M.P. “Pete” Frank, Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin, and Clifford E. Charlesworth, gathered to celebrate the end of the 10-day flight. Top NASA Managers such as Rocco A. Petrone, Apollo Program Director at Headquarters, Director of Flight Operations Christopher C. Kraft, Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager James A. McDivitt, and MSC Director Robert L. Gilruth, joined in the celebrations.

Left: In Mission Control, Apollo 12 Flight Directors Lunney, Frank, Griffin, and Charlesworth celebrate the successful splashdown of Apollo 12. Right: NASA managers Petrone, Kraft, McDivitt, and Gilruth celebrate the successful splashdown with the traditional lighting of cigars.

Left: UDT swimmers on Yankee Clipper as Hornet approaches for the pickup. Right: Recovery forces lift Yankee Clipper out of the water. Credits: US Navy.

Within an hour after the astronauts arrived on board Hornet, the UDT swimmers and sailors aboard Hornet hauled Yankee Clipper out of the water and towed it below to the hangar deck next to the MQF. Once the capsule was secured, Hornet set sail for Pearl Harbor, arriving there four days later. Workers attached a hermetically sealed plastic tunnel between the MQF and Yankee Clipper, allowing Stone to leave the MQF and open the hatch to the capsule without breaking the biological barrier. He retrieved the two Sample Return Containers (SRC) containing the lunar samples, the bags containing the Surveyor parts, film cassettes, and mission logs from the capsule and returned them to the MQF. Stone sealed the SRCs, film cassettes, and medical samples taken inside the MQF in plastic bags and transferred them to the outside through a transfer lock that included a decontamination wash. Outside the MQF, NASA engineers placed these items into transport containers and loaded them aboard two separate aircraft. The first aircraft, a C-2 Greyhound, carrying one SRC and a second package containing film departed Hornet within nine hours of the recovery, flying to Pago Pago 380 miles to the west. From there the two containers were placed aboard a C-141 Starlifter cargo aircraft and flown directly to Ellington Air Force Base (AFB) near MSC in Houston, arriving there late in the afternoon of Nov. 25. A second C-2 departed Hornet 14 hours after the first and included the second SRC, additional film as well as the astronaut medical samples. It flew to Pago Pago where workers transferred the containers to another cargo plane that flew them to Houston. Less than 48 hours after splashdown, scientists in the LRL were examining the lunar samples and processing the film.