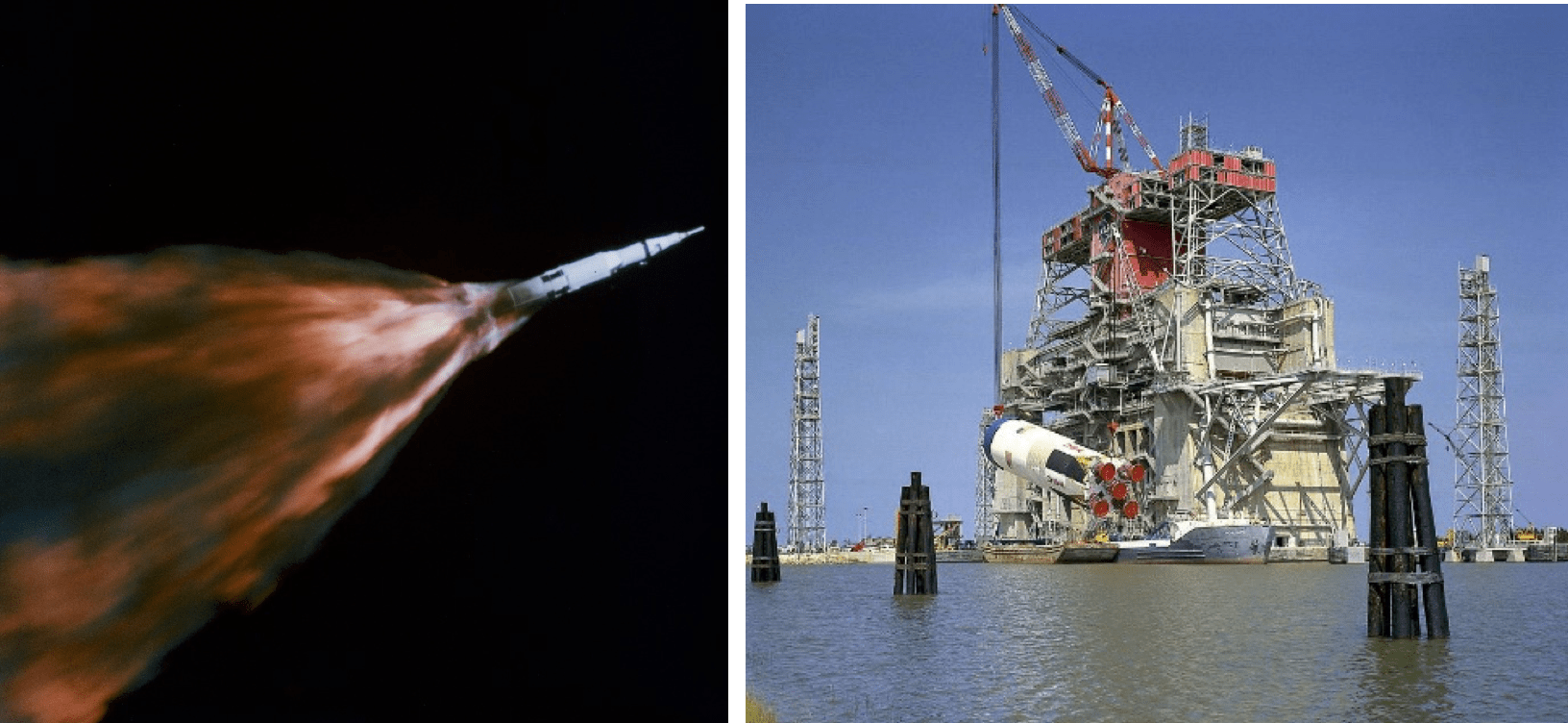

On July 18, 1968, NASA announced that engineers had found a solution to the problem that occurred near the end of the Saturn V rocket’s first stage during the uncrewed Apollo 6 mission. During the last ten seconds of that first stage burn, the rocket experienced longitudinal oscillations called “pogo effect.” Pogo occurred when a partial vacuum in the fuel and oxidizer feed lines reached the engine firing chamber causing the engine to skip. These oscillations then traveled up the axis of the launch vehicle resulting in intense vibration in the Command Module and causing some superficial structural damage to the Spacecraft Lunar Module Adaptor (SLA). Had a crew been onboard, they would have experienced severe vibrations and even possible injury.

The pogo problem was nothing new to the world of rocketry. Early launch vehicles such as the Thor, and even the Titan II used for the Gemini program, had a similar experience, as did, to a lesser degree, the Saturn V during the Apollo 4 mission. Arguing that any crew would have survived the flight aboard Apollo 6, Marshall Space Flight Center Director Wernher von Braun conceded that the “flight clearly left a lot to be desired. With [this problem], we just cannot go to the Moon.” Once NASA decided to place a crew on Apollo 8, the next flight of the Saturn V, solving the pogo issue took on critical importance. A recurrence of pogo on Apollo 8 could risk the mission being aborted and possible injury to the crew.

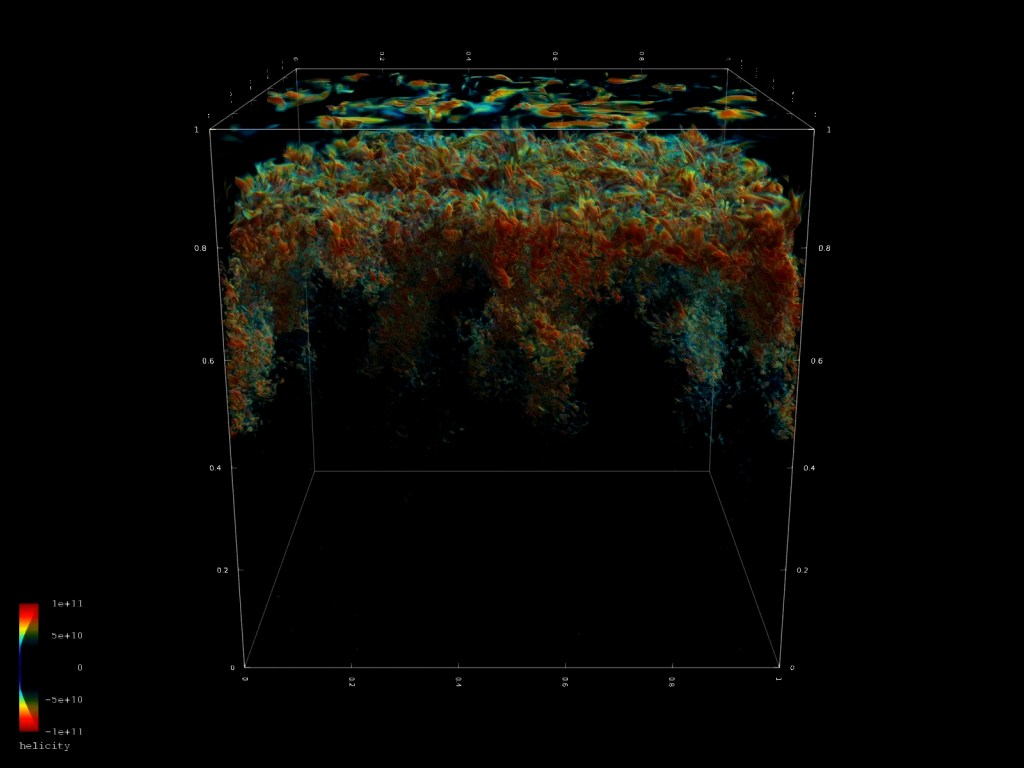

NASA formed a Pogo Working Group comprised of more than 1,000 government and industry engineers to come up with a solution capable of verification through ground testing. The Working Group organized a rigorous investigation, which determined the key to mitigating the pogo effect included ‘de-tuning’ the rocket’s engine to change the frequency of the vibration it produced by filling the prevalve cavities on the liquid oxygen (LOX) feed lines with helium gas. Injecting helium into those lines prior to ignition would effectively work as a shock absorber to prevent the oscillations from traveling up and down fuel and oxidizer feed lines.

Engineers developed mathematical models based upon previous flights and verified them through a series of tests, then conducted static test firings of first stages for upcoming missions with pogo suppression hardware installed. On July 15, Apollo Program Director Samuel C. Phillips and George Mueller, NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, concurred with the group’s solution. The success of the test program gave NASA the confidence to continue plans for a crewed Apollo 8 mission that December and the decision brought the Moon landing one step closer.