Skylab, America’s first space station and the first crewed research laboratory in space, lifted off on May 14, 1973. Skylab enabled research in several areas, including the astronauts’ physiological responses to long-duration space flight, Earth sciences, and solar physics and astronomy, with additional experiments in materials processing. During launch, Skylab lost its micrometeoroid shield that also provided thermal protection. Debris from the shield jammed one of its power-generating solar array wings and it lost the other wing completely. Managers delayed the launch of the Skylab 2 crew of Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Pilot Paul J. Weitz, and Science Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin, as engineers devised plans to save the overheating and underpowered space station. The trio launched on May 25, inspected the station, finally docked. The next day they erected a sunshade over the station to lower its temperature.

Left: Skylab 2 astronauts Paul J. Weitz, left, Charles “Pete” Conrad, and Joseph P. Kerwin

pose in front of a T-38 Talon jet at Ellington Air Force Base in Houston prior to

their departure for NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for the first launch

attempt. Right: Launch of Skylab 1, with Skylab 2 in foreground.

During its launch on May 14, 1973, the Skylab 1 space station suffered significant damage that tore off its micrometeoroid shield, that also acted as a thermal shield, jammed one of its power-generating solar array wings, and tore the other wing completely off the vehicle. After reaching orbit as planned, the station jettisoned its payload shroud and deployed the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) with its four smaller solar arrays. But controllers in Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, led by Flight Director Donald R. Puddy, grew concerned as temperatures inside the unprotected station rose to alarmingly high levels. The high temperatures would not only make it impossible for the astronauts to live and work aboard the station, but could possibly ruin sensitive film and food supplies, and even potentially cause insulating materials to give off toxic gases. Mission managers postponed the crew’s launch, planned for the following day, by at least five days so engineers could better assess the situation and devise plans to first cool the station, and then free the jammed solar array wing. As that work took longer than first anticipated, they delayed the launch another five days, to May 25. Engineers in Mission Control devised an attitude plan for Skylab that maximized power generation from the ATM’s solar arrays yet minimized direct solar exposure to keep internal temperatures as low as feasible.

Left: Dale Gentry, left, and James H. Barnett, right, assist seamstresses Elizabeth Gauldin

and Alyene Baker in the fabrication of the parasol sunshade. Middle left: Technicians in the

Technical Services Division of NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston assemble the

parasol sunshade. Middle right: JSC Director Christopher C. Kraft, left, receives a

briefing on the parasol sunshade. Right: Demonstration of

the deployment of the parasol sunshade.

Teams of engineers at JSC and at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama, came up with three possible solutions to cool the space station. One option called the twin-pole sunshade required two astronauts to conduct a spacewalk to attach it to the station’s exterior. Managers believed this would provide the best shading for the station but also deemed it too complex given the training time available, and decided to launch it but let Skylab’s second crew deploy it. A second option involved attaching a sunshade by one of the astronauts standing in the open hatch of the Apollo Command Module (CM) as another flew the spacecraft down the length of the station. While managers considered this option the most challenging, they decided to fly the hardware anyway. The third, and the one managers ultimately chose for the Skylab 2 crew, involved deploying a parasol-like sunshade from inside Skylab using one of its scientific airlocks. While they didn’t consider this a permanent solution, it seemed the least complex and would yield nearly immediate results. Jack A. Kinzler, chief of the Technical Services Division at JSC and who also designed the Apollo 11 U.S. flag, designed the parasol by attaching a 22-by-24-foot fabric sheet made of nylon, Mylar, and aluminum to the ends of four fishing rods, the folded assembly pushed through the airlock using segments of metal poles. Once the spring loaded fishing rods extended, the astronauts would retract the flat parasol so it fit snugly against Skylab’s exterior. As a downside to this solution, experiments that relied on the scientific airlock no longer had that facility available. The parasol, packed by professional parachute riggers, fit inside an 8-inch square container 53 inches long, small enough to fit inside the Apollo CM.

Left: The Skylab 2 crew of Dr. Joseph P. Kerwin, left, Charles “Pete” Conrad, and Paul J. Weitz.

Middle: The official Skylab 2 crew patch. Right: Liftoff of Skylab 2 from Launch

Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

With the three parasols and extra tools packed below their seats, Conrad, Weitz, and Kerwin climbed aboard their Apollo spacecraft. The Saturn IB rocket lifted off from Launch Pad 39B at 9 a.m. EDT on May 25, 1973. As soon as the rocket cleared the launch tower, Mission Control at JSC took over monitoring the flight, led by Flight Director Philip C. Shaffer, with astronaut Richard H. Truly serving as capsule communicator (capcom). Soon after separating from the rocket’s S-IVB second stage, the astronauts began the seven-hour chase to catch up to Skylab.

Left: View of the Skylab 1 space station, televised by the Skylab 2 crew during their

initial flyaround inspection, showing the missing micrometeoroid shield and the

one jammed solar array wing. Right: View in Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson

Space Center in Houston during the flyaround inspection.

“Tally ho the Skylab!” Conrad radioed from 1.5 miles away. As they approached even closer, they could see that as expected, Skylab’s skin was the gold Mylar, not the black and white of the now missing micrometeoroid shield, that one solar array was “completely off the bird,” and the second array only open about 15 degrees instead of the expected 90, held down by debris from the lost shield. On closer inspection, the gold material had turned black and even bubbled from the 11 days of exposure to the Sun’s scorching rays. The flyaround inspection completed, Conrad steered the CSM to the station’s forward docking port and as planned brought the spacecraft in for a soft docking, meaning the Apollo’s docking probe engaged in the drogue on the station side, but the latches did not engage. In this configuration, they ate dinner, discussed the next steps, and undocked 49 minutes later.

Left: Photograph of the damaged Skylab 1 space station, taken by the Skylab 2 crew during the

flyaround inspection, with loose wiring showing the location of the missing solar array wing,

at top, the missing micrometeoroid shield, and the jammed solar array wing, at bottom.

Middle: Closeup view of the debris from the torn micrometeoroid shield that pinned the

one remaining solar array wing. Right: External view of the Sun-facing scientific

airlock that the Skylab 2 crew used to deploy the parasol sunshade.

Conrad flew the spacecraft back to the aft end of the station near the end of the partially deployed solar array wing. They depressurized the spacecraft, opened the hatch, and with Conrad flying to keep the spacecraft in position, Weitz stood up in the hatch with Kerwin holding his legs to keep him from floating away. With Conrad flying the spacecraft sometimes as close as 2 feet from the solar wing, Weitz used a shepherd’s hook tool at the end of a 10-foot pole to try to pull the array free. He exerted enough force that the wing moved about one foot, but it stubbornly refused to open, pinned by a half-inch strap of metal. The effort also caused the Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) to pull closer to Skylab and even pulled the station closer, causing its thrusters to fire. Fearing a collision, Conrad fired thrusters to pull away, with the hook still attached to the wing, nearly pulling Weitz out of the spacecraft. They next attempted to cut the metal strap keeping the solar wing pinned, switching the hook to a double prong hook, but Weitz couldn’t get a good angle on it, and it proved too thick to cut. With orbital darkness approaching, Conrad decided to call off the attempt. They closed the hatch, repressurized the spacecraft, and headed back to the forward docking port. Their first attempt to soft dock did not succeed. Neither did their second, nor their third, nor even their fourth. Conrad attempted to dock at slower speed and faster speed, with no success. They once again depressurized the spacecraft so they could open the forward hatch to bypass some electrical connections, until finally on the eighth attempt, after using an emergency backup procedure, they achieved first a soft docking, and then a hard docking. The astronauts cleaned up the spacecraft and went to sleep, after a very eventful 22-hour day. The next morning, they sampled the air in the Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA) using a toluene diisocyanate (TDI) detector developed specifically for this mission. Levels of TDI would indicate that the heat aboard the station caused some of the insulation to break down. They opened the hatch and wearing gas masks entered the MDA to activate it and the Airlock Module and ATM. Because these two modules were still closed off to the main workshop, the temperature remained in the 50s. With Conrad beginning the process of deactivating the CSM, Weitz and Kerwin began activating the MDA and ATM, respectively.

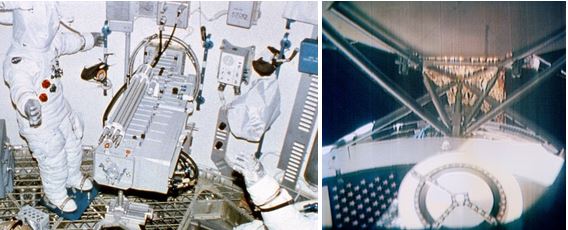

Left: The container for the parasol sunshade shown attached to the Sun-facing

scientific airlock in the Skylab workshop. Right: Still from a television downlink

of the parasol deployment as seen from the Apollo Command Module.

Wearing a mask, Weitz entered the workshop first, spending five minutes inside to activate the module’s fans. Kerwin later used the TDI detector to confirm the absence of the toxic gas in the workshop. The temperature hovered around an estimated 125-130 degrees F, but with the low humidity, Weitz later described it as feeling like a desert heat. Other than starting the activation of the station, one of the high priority tasks for this day included the deployment of the parasol to begin cooling the station. They brought the assembly from the CM and installed the canister onto the scientific airlock on the Sun-facing side of the workshop. Although they worked in the relative comfort of the pressurized workshop, the heat forced them to periodically retreat to the CM to cool off and rehydrate. Conrad assembled the components of the parasol and began pushing the rods through the airlock. With Kerwin watching from the CM, the parasol extended to its full length and its folded arms swung out, spreading out the fabric. Conrad retracted the pole so that the parasol lay flush against the workshop’s skin, although it did not fully deploy due to crinkling of the fabric. Temperatures in the workshop began to decrease. The astronauts kept all the station’s hatches and spent another night sleeping in the CM.

Three views from television downlinks of life and work aboard Skylab following the deployment of

the parasol sunshade. Left: Dr. Joseph P. Kerwin, right, drawing a blood sample from Charles

“Pete” Conrad. Middle: Conrad at the controls of the Apollo Telescope Mount in the Multiple

Docking Adapter. Right: Conrad prepares a meal in Skylab’s wardroom.

Over the next several days, as temperatures in the workshop continued to drop into more comfortable ranges, the astronauts tried to return to their preflight timelines. High priority activities included setting up the wardroom and the workshop’s water supply system so they could eat their meals in the station instead of the less efficient CM, activating the film vault, checking the status of the food supply, and activating the waste management system. For the next three nights, with the workshop still too hot, they slept in the much cooler MDA. At the start of their fourth day, May 28, the astronauts ate their first breakfast in the wardroom. That day, with temperatures still warm but dropping every hour, they began their mission’s science experiments, with Weitz completing the first session in the Lower Body Negative Device, with Kerwin observing, to track changes in his cardiovascular system. Weitz curtailed his ride on the bicycle ergometer due to the heat. Kerwin also collected the first blood sample from Conrad. They held a televised press conference from the wardroom and Mission Control completed a ground-commanded checkout of the ATM, with the first crew-tended operations on the fifth day. After spending their first night in their sleep stations in the workshop, on the sixth day they completed the first session of the vestibular experiment in the rotating chair and took the first photos with the Earth Resources Experiment Package. With the expansion of the science program, the reduced available power levels resulted in Mission Control needing to delay some activities. Getting the stuck solar array wing deployed took on greater importance to finish not only the research on this first mission but the next two longer flights as well.

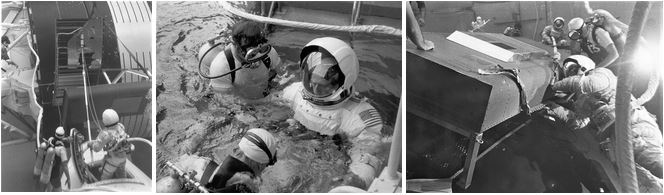

Left: Skylab 2 astronaut Paul J. Weitz training for a procedure to free Skylab’s jammed solar

array wing during a standup spacewalk in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at NASA’s

Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Middle: Skylab 2 astronaut

Charles “Pete” Conrad prepares to dive for spacewalk training in the NBS.

Right: In the NBS, backup Skylab 2 commander Russell L. Schweickart

practices cutting through a metal strap jamming

Skylab’s remaining solar array wing.

Backup Skylab 2 Commander Russell L. Schweickart led a tiger team to develop various procedures for freeing the jammed solar array. Using the televised images, crew descriptions, and other available information about the nature of the debris, most likely a half-inch wide strap with a bolt embedded into the wing itself. The first proposed attempt, Weitz’s standup spacewalk, proved ineffective. More complicated procedures involved Conrad and Kerwin conducting a spacewalk from the Skylab airlock and using a cutting tool at the end of a long pole to cut the strap. Schweickart and other astronauts practiced these techniques in MSFC’s Neutral Buoyancy Simulator. Aboard Skylab, in the days leading up to the spacewalk, on June 2 Conrad celebrated his 43rd birthday, the first American to mark an anniversary in space – Soviet cosmonaut Viktor I. Patsayev did it first aboard Salyut in June 1971.