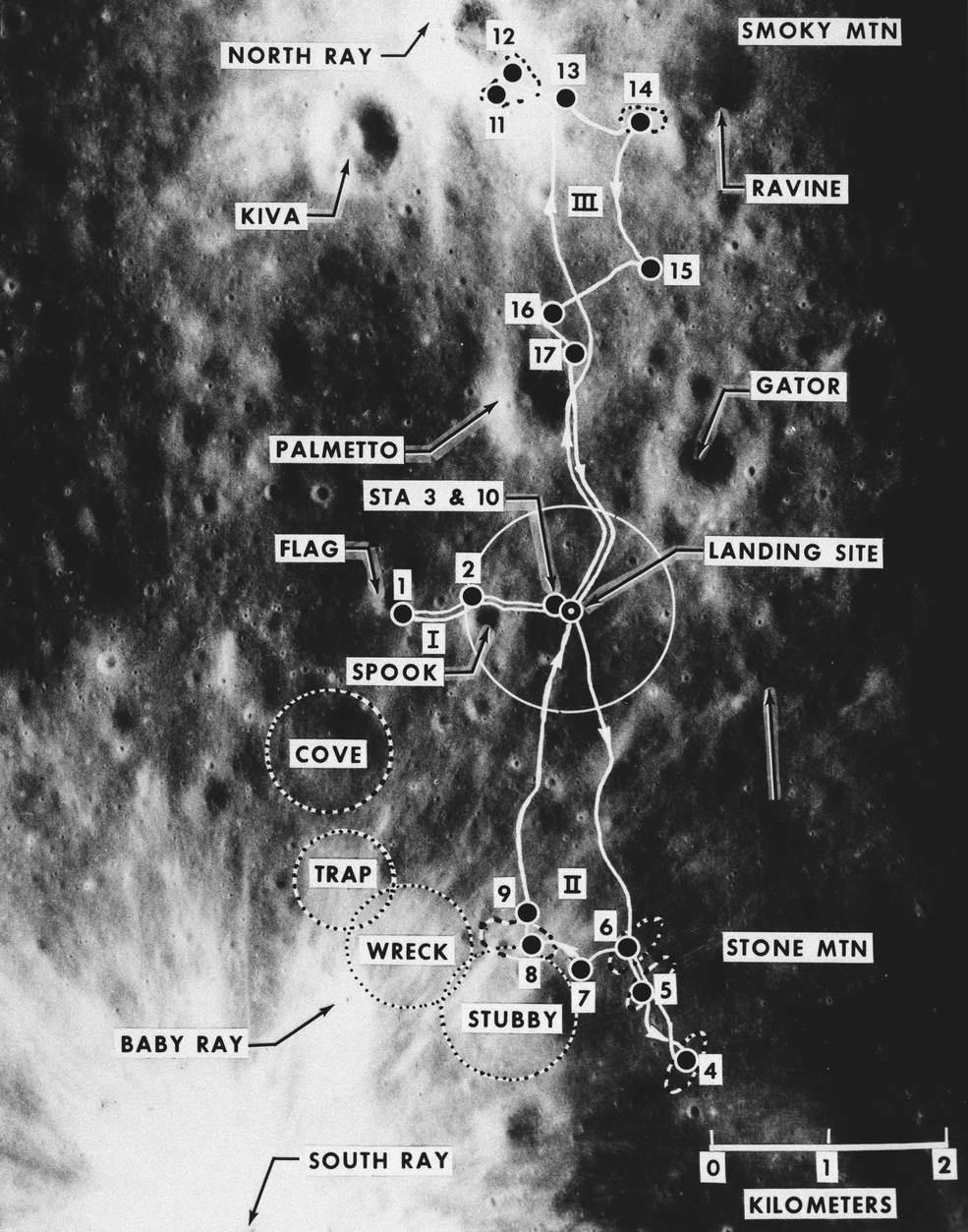

In January 1972, multiple issues led NASA managers to announce a one-month launch delay of Apollo 16 from March to April 1972. Later in the month, the mission faced even more trouble after a Command Module fuel tank damaged during a test required a rollback of the Saturn V stack from the launch pad to execute a replacement. With extra time, the crew of Commander John W. Young, Command Module Pilot Thomas K. Mattingly, and Lunar Module Pilot Charles M. Duke and their backups Fred W. Haise, Stuart A. Roosa, and Edgar D. Mitchell, continued training for the fifth lunar landing, a 12-day mission to the Descartes site in the Moon’s highlands. In addition to extensive simulator training, the astronauts prepared for the three lunar surface traverses and orbital observations.

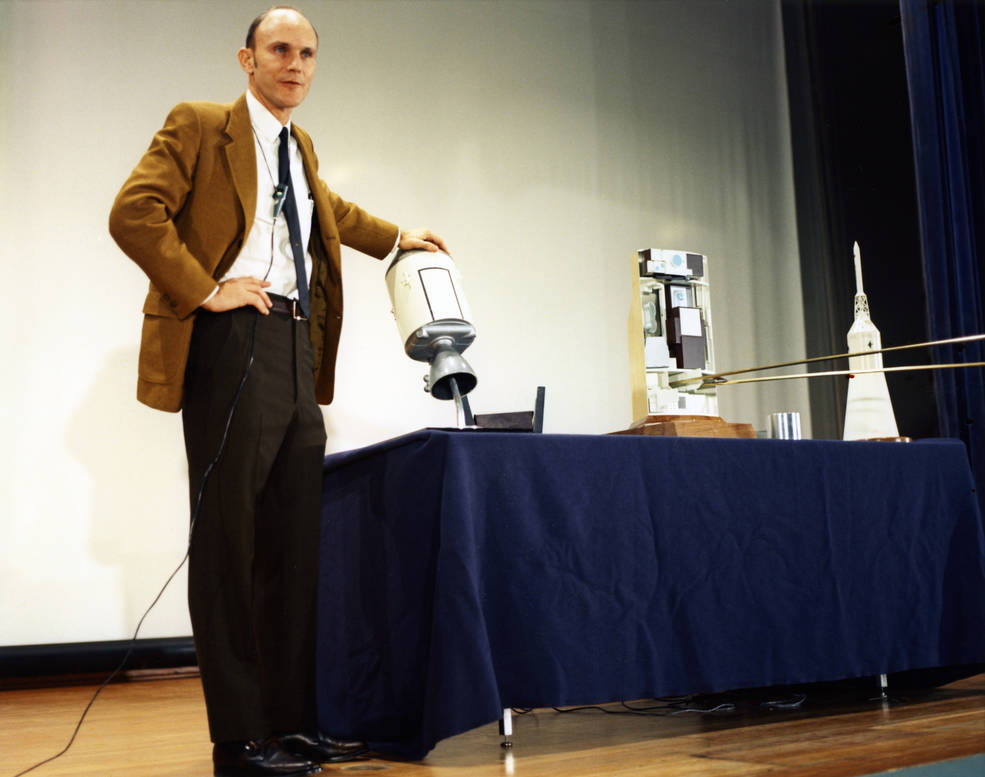

Left: Apollo 16 astronaut Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly uses models of the Command and Service Modules and the Scientific Instrument Module during a press conference at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: Apollo 16 astronauts Charles M. Duke, left, and John W. Young practice lunar surface activities at KSC. Right: A diagram of the three planned Apollo 16 lunar surface traverses at the Descartes landing site.

The year started off on a sour note for Duke. He had begun to feel ill during the crew’s December 1971 geology field trip to Hawaii. He managed to fly to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on Jan. 3, but his condition worsened. The next day, doctors diagnosed him with double bacterial pneumonia and admitted him to the Patrick Air Force Base hospital near KSC for treatment. The other crew members were not affected by Duke’s illness and continued their activities while he spent a week in the hospital recovering. On Jan. 6, Mattingly held a press conference at KSC to discuss his role in the mission. As the Command Module Pilot, Mattingly stayed in orbit while Young and Duke explored the lunar surface, conducting visual and photographic observations and using instruments in the Service Module’s Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay. He described how Young and Duke might obtain samples of the Moon’s original surface at the Descartes site. In the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) Water Immersion Facility, Mattingly and his backup Roosa practiced the deep-space spacewalk to retrieve film cassettes from the SIM-bay instruments. Young and Duke, and their backups Haise and Mitchell, rehearsed the lunar surface activities including driving the Lunar Roving Vehicle at KSC. Young and Haise practiced the descent to and landing on the Moon using the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle at Ellington Air Force Base near MSC. The backup crew of Haise, Roosa, and Mitchell conducted water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico on Jan. 22, an activity the prime crew completed two weeks later. All crew members received extensive geology briefings by a team of geologists.

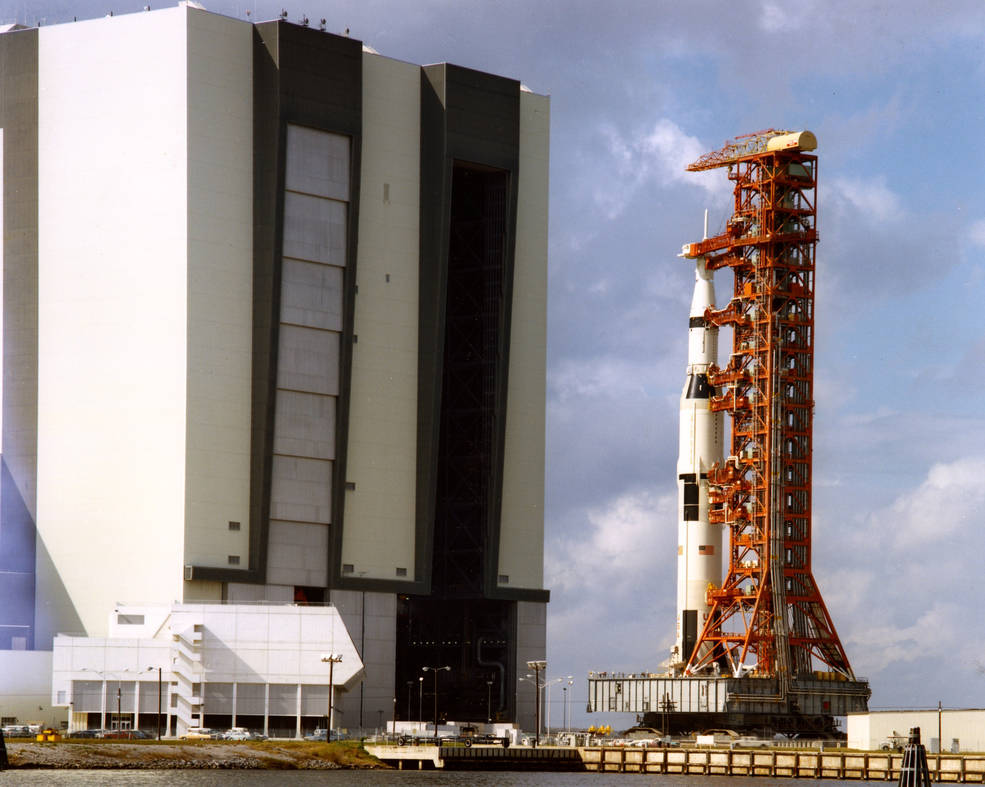

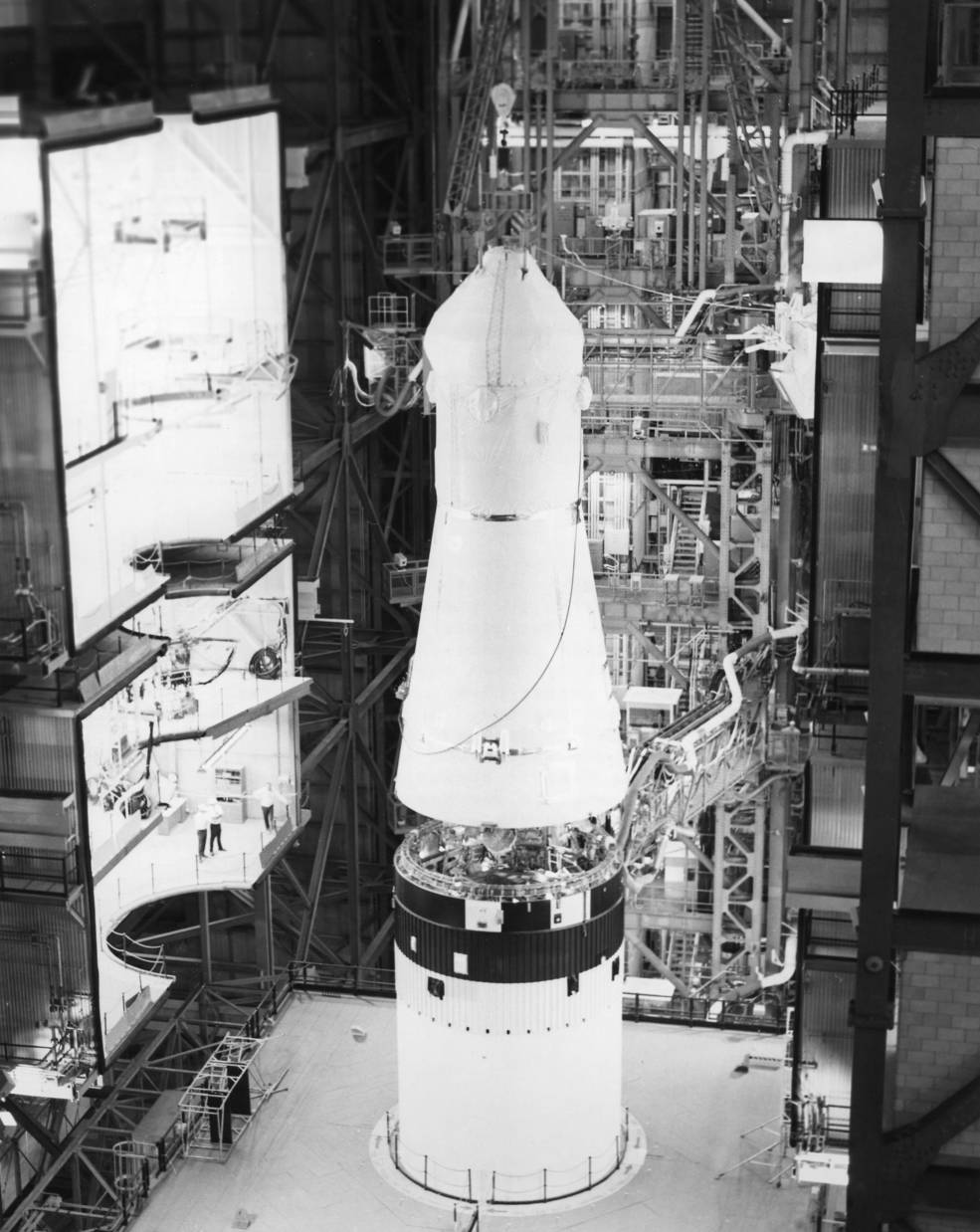

Left: The Apollo 16 Saturn V begins its rollback from Launch Pad 39A to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Right: The Saturn V nears the VAB during the rollback.

On Jan. 7, NASA managers announced a one-month slip in Apollo 16’s launch date from March 17 to the next opportunity on April 16. Several factors led to the decision to delay the launch. First, testing of modifications to Young and Duke’s spacesuits to enable them to bend more easily to pick up samples would not be completed in time to support the March launch date. Second, extensive testing of the Command Module’s docking ring jettison device was required following a failure of the device during a test for the Skylab program, and would not be finished in time for a March launch. And third, additional data were required by engineers to reverify the Lunar Module’s battery’s capacity. All these activities were completed to meet the new April launch date. Although doctors did not expect Duke’s illness to affect the original launch date, the delay gave Duke additional time to recover and resume his training. On Jan. 10, NASA released an updated Apollo 16 preliminary timeline based on the new launch date. On Jan. 25, during a test at Launch Pad 39A, workers accidentally over pressurized a fuel tank in the Command Module’s reaction control system. The resulting damage required a replacement of the tank, an activity that could not be performed at the pad. On Jan. 27, the entire Saturn V rolled back from the pad to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), only the second time a Moon rocket returned to the VAB while at the pad for testing – the first took place in June 1966, to keep the Saturn 500F test vehicle out of harm’s way of an approaching hurricane – and the one and only time with a flight vehicle.

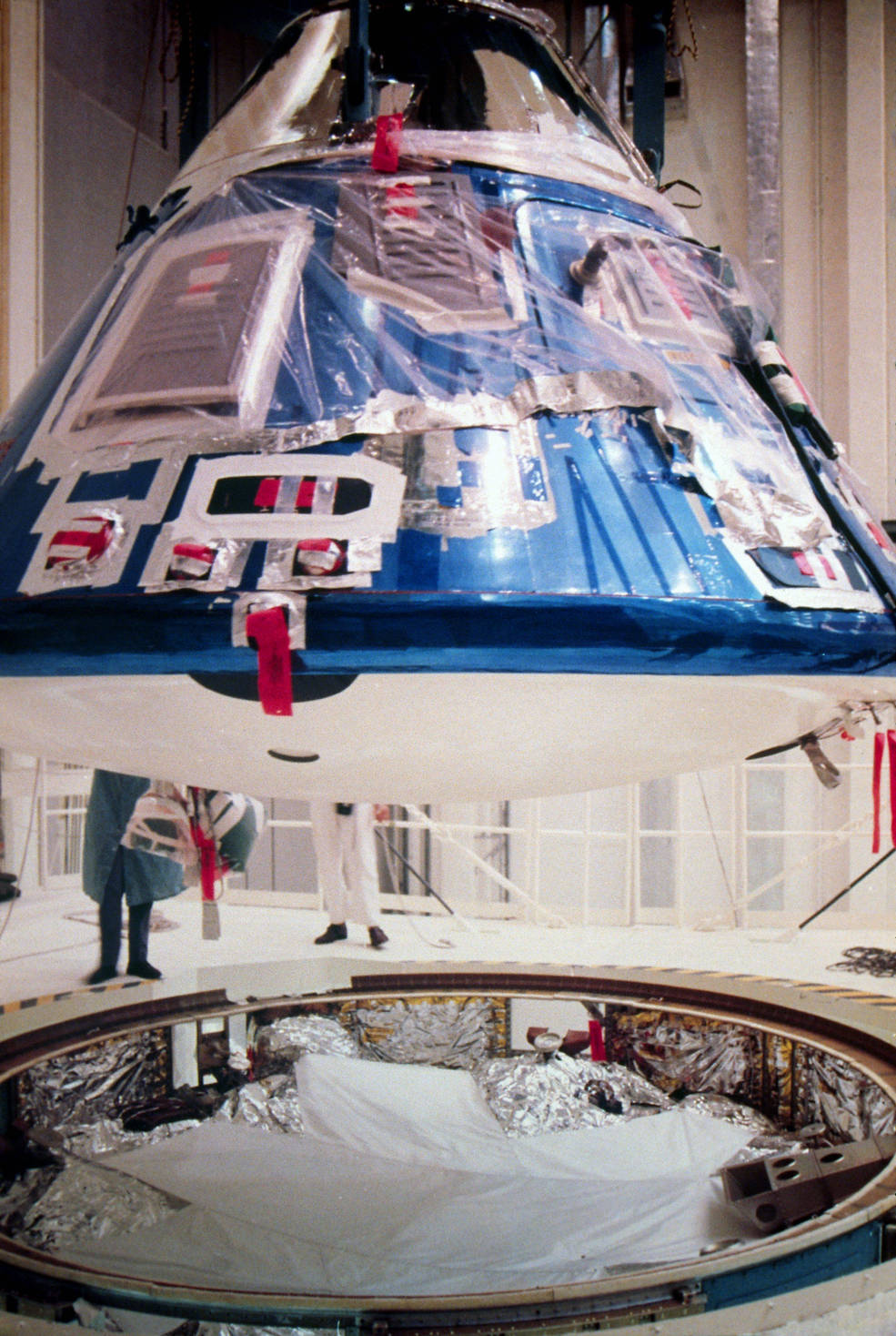

Left: Workers destack the Apollo 16 spacecraft from its Saturn V rocket in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: The Apollo 16 spacecraft exits the VAB on its way to the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB) at KSC. Right: In the MSOB, workers lift the Apollo 16 Command Module from its Service Module in preparation for replacement of the fuel tank damaged during a test.

Once in the VAB, workers first removed the Launch Escape System tower and then destacked the spacecraft from the Saturn V rocket, trucking it to the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB). In the MSOB, technicians demated the Command Module from the Service Module, removed its heat shield, and replaced the damaged fuel tank. The repair completed, workers reversed the process to reassemble the spacecraft, stacked it on top of the Saturn V rocket, and rolled the assembled vehicle back to the pad in two weeks, in time to support the April 16 launch date.

Apollo 17 astronauts Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt, left, and Eugene A. Cernan ride the Explorer, a ground-based trainer for the Lunar Roving Vehicle, during a geology field trip to Boulder City, Nevada.

While the Apollo 16 mission drew close to its launch, the astronauts for the next and final Moon landing mission, Apollo 17, already busied themselves with geology and other training. Moonwalkers Eugene A. Cernan and Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt, with support astronauts Robert A.R. Parker and Joseph P. Allen and a team of geologists, traveled to Boulder City, Nevada, for a geology field trip. President Richard M. Nixon’s Science Advisor Edward E. David and his wife attended as observers. During the two-day trip, Cernan and Schmitt practiced their second and third lunar traverses, using a ground-based training version of the Lunar Roving Vehicle called Explorer. The third Apollo 17 astronaut, Ronald E. Evans, conducted a flyover of the area to review the traverses in the context of the regional geology, much as he would from lunar orbit.

Other events at MSC in January 1972

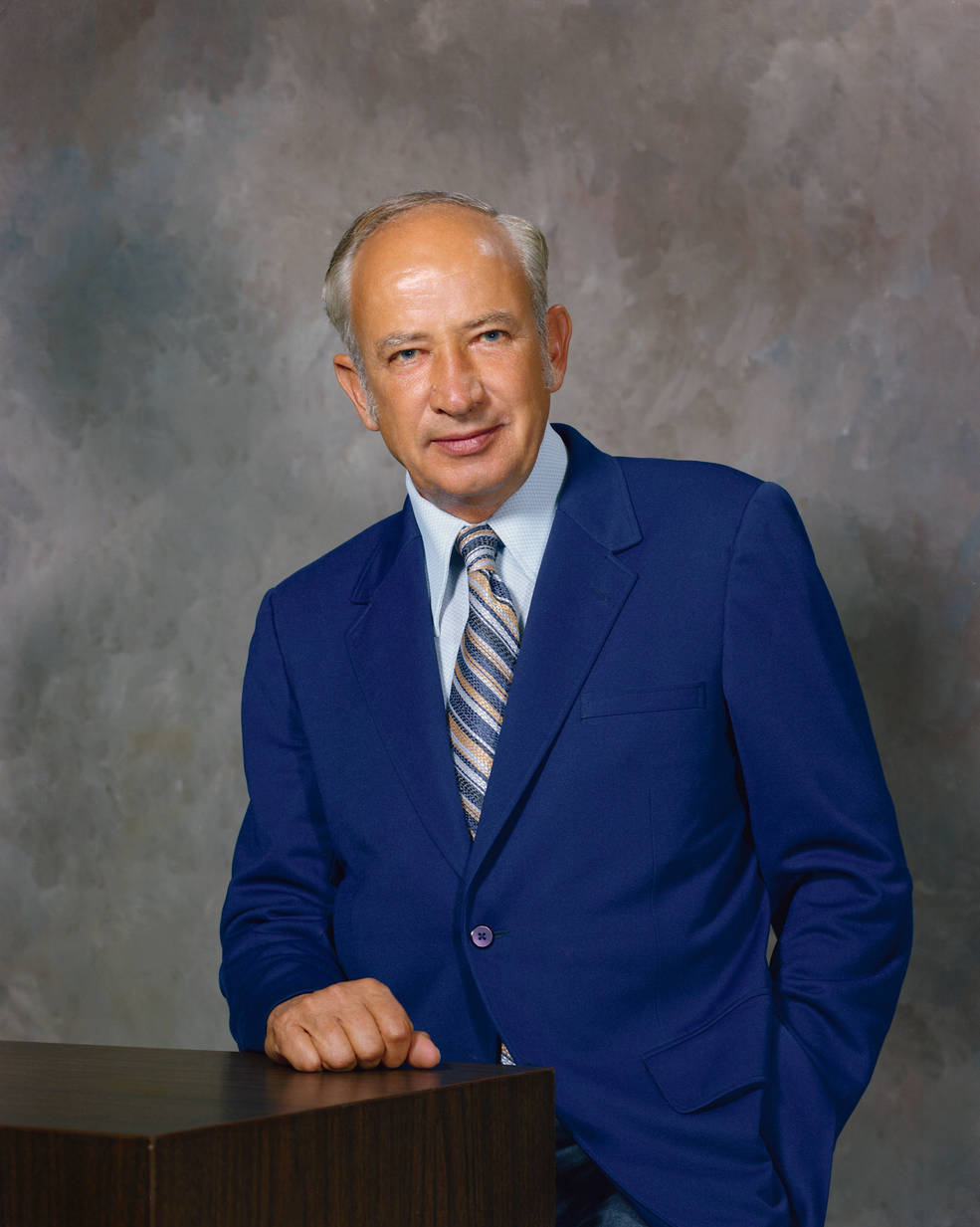

Left: Attendees at the Third Annual Lunar Science Conference mingle in the lobby outside the auditorium at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Right: MSC deputy Director welcomes the attendees to the Third Annual Lunar Science Conference.

From Jan. 10-13, more than 600 scientists from the U.S. and 13 other nations attended the third annual Lunar Science Conference, held for the first time at MSC. Deputy Director Christopher C. Kraft welcomed the attendees to the conference. Other NASA speakers included Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager James A. McDivitt and Apollo 15 astronauts David R. Scott, Alfred M. Worden, and James B. Irwin, who spoke about their personal observations of the Moon. Soviet delegates discussed the results from their Luna-16 sample return spacecraft and their Lunokhod-1 lunar rover. As part of an exchange agreement between the two nations, NASA provided the Soviet delegation with three grams of lunar soil returned by Apollo 14.

Left: Photograph of Robert R. Gilruth, the first director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, taken in Mission Control during the Apollo 11 mission. Middle: Portrait of Christopher C. Kraft, MSC’s second director. Right: Portrait of Sigurd A. “Sig” Sjoberg, named as MSC deputy director under Kraft.

On Jan. 14, NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher announced the appointment of MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth to the newly-created position of Director of Key Personnel Development. In this new position, Gilruth identified and prepared future leaders across the agency while remaining in Houston. Fletcher named MSC Deputy Director Christopher C. Kraft to succeed Gilruth as the center’s second director. On Jan. 18, Kraft named Director of Flight Operations Sigurd A. “Sig” Sjoberg as MSC’s deputy director.

Left: Joseph P. Kerwin, left, Charles “Pete” Conrad, and Paul J. Weitz, the crew of Skylab-2. Middle: The Skylab-3 crew of Owen K. Garriott, Alan L. Bean, and Jack R. Lousma. Right: Skylab-4 astronauts Edward G. Gibson, Gerald P. Carr, and William R. Pogue.

On Jan. 18, 1972, MSC announced the astronauts who would conduct long-duration missions aboard America’s first experimental space station, Skylab. The orbiting facility, then planned for launch in April 1973, would house three three-person crews for visits lasting 28, 56, and 56 days. Assigned to the first mission, called Skylab-2, were Gemini-XI and Apollo 12 veteran Charles “Pete” Conrad as commander and space rookies Joseph P. Kerwin as science pilot and Paul J. Weitz as pilot. Their backups were Apollo 9 veteran Russell L. Schweickart and rookies F. Story Musgrave and Bruce McCandless. The Skylab-3 crew consisted of Apollo 12 veteran Alan L. Bean as commander and rookies Owen K. Garriott as science pilot and Jack R. Lousma as pilot. The all-rookie crew of commander Gerald P. Carr, Edward G. Gibson, and pilot William R. Pogue made up the Skylab-4 crew. Vance D. Brand, William B. Lenoir, and Don L. Lind, all spaceflight rookies, comprised the backup crew for both Skylab-3 and Skylab-4. To prepare for space station science operations, the first Skylab experiment planning simulation began in late January in MSC’s Mission Control Center.

To be continued…

World events in January 1972

January 1 – Kurt Waldheim of Austria becomes the United Nations Secretary General.

January 3 – Mariner 9 begins its mapping mission of Mars after the global dust storm subsides.

January 5 – President Richard M. Nixon directs NASA to build the space shuttle.

January 7 – Lewis F. Powell and William H. Rehnquist are sworn in as U.S. Supreme Court justices.

January 14 – “Sanford & Son” starring Redd Foxx and Demond Wilson premieres on NBC.

January 16 – The Dallas Cowboys win their first NFL championship, defeating the Miami Dolphins in Super Bowl VI in New Orleans.

January 18 – Dr. Baruch S. Blumberg is awarded a U.S. patent for a vaccine against hepatitis B.

January 27 – The first home video game system, a two-player tennis-like game called Odyssey, is introduced by Magnavox.