On Aug. 2, 1971, following three days of exploration at the Hadley-Apennine site on the Moon, Apollo 15 astronauts David R. Scott, and James B. Irwin lifted off aboard the Lunar Module (LM) Falcon to rejoin Alfred M. Worden, who had been conducting science from lunar orbit aboard the Command Module (CM) Endeavour to characterize the Moon’s surface and environment. Part of that science included placing a subsatellite into lunar orbit shortly before the astronauts began their trip back to Earth. During the three-day voyage home, Worden conducted the first cislunar spacewalk to retrieve film canisters from cameras located in the spacecraft’s Service Module. The astronauts observed a total lunar eclipse, held an inflight press conference to provide their views of the mission for reporters, and prepared their spacecraft for reentry and splashdown.

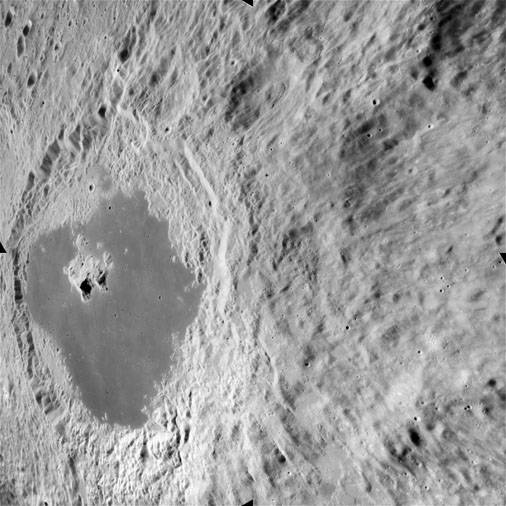

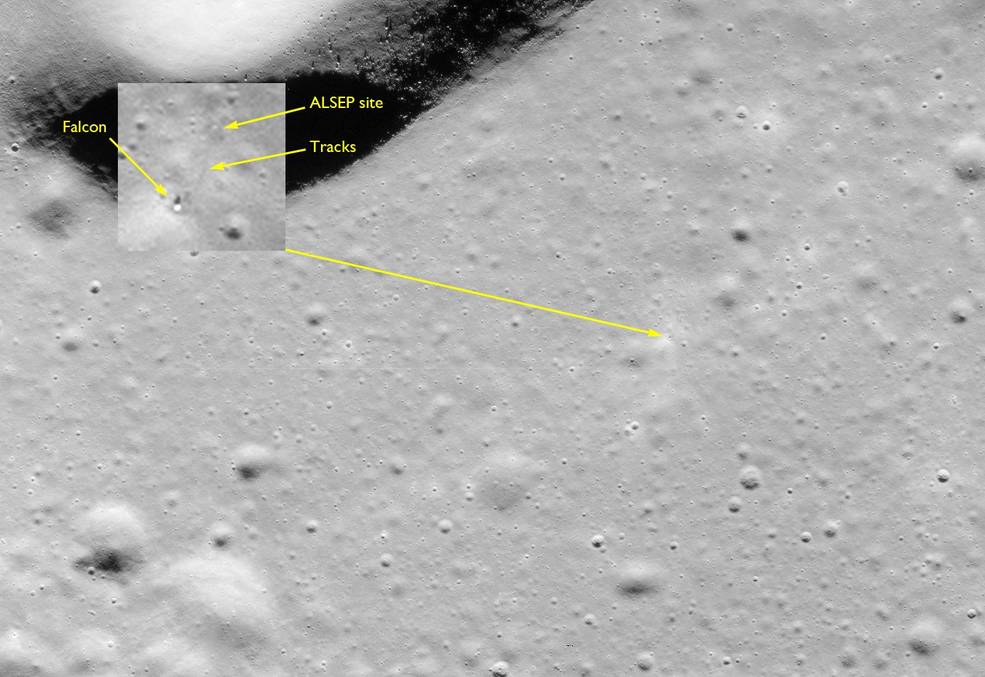

Left: The farside Tsiolkovsky Crater imaged by the Orbital Mapping Camera. Right: A detail from a Panoramic Camera image showing the Lunar Module Falcon and the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package on the Plain at Hadley, magnified in the inset, with Hadley Rille at top.

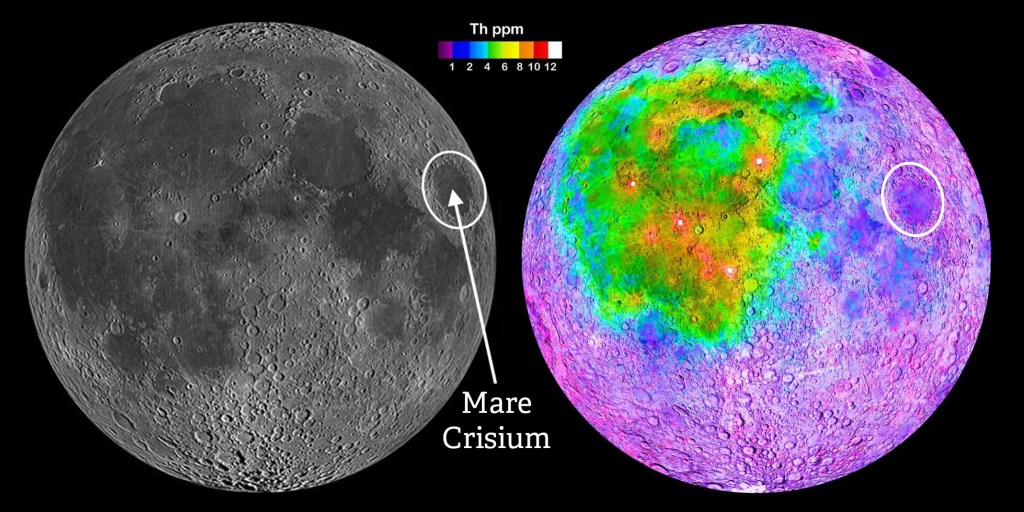

During the three days that Scott and Irwin explored the lunar surface, Worden kept busy in lunar orbit managing the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay experiments and cameras. During his 34 solo revolutions around the Moon, he photographed the lunar surface, both the nearside and the less well-documented farside, mapped the chemical composition of the lunar surface using X-ray and gamma-ray spectrometers, mapped the overall geometry of the Moon, and measured the tenuous lunar atmosphere. Precise tracking of Endeavour’s orbit allowed better characterization of mass concentrations, or mascons, beneath the lunar surface that cause perturbations in the spacecraft’s trajectory.

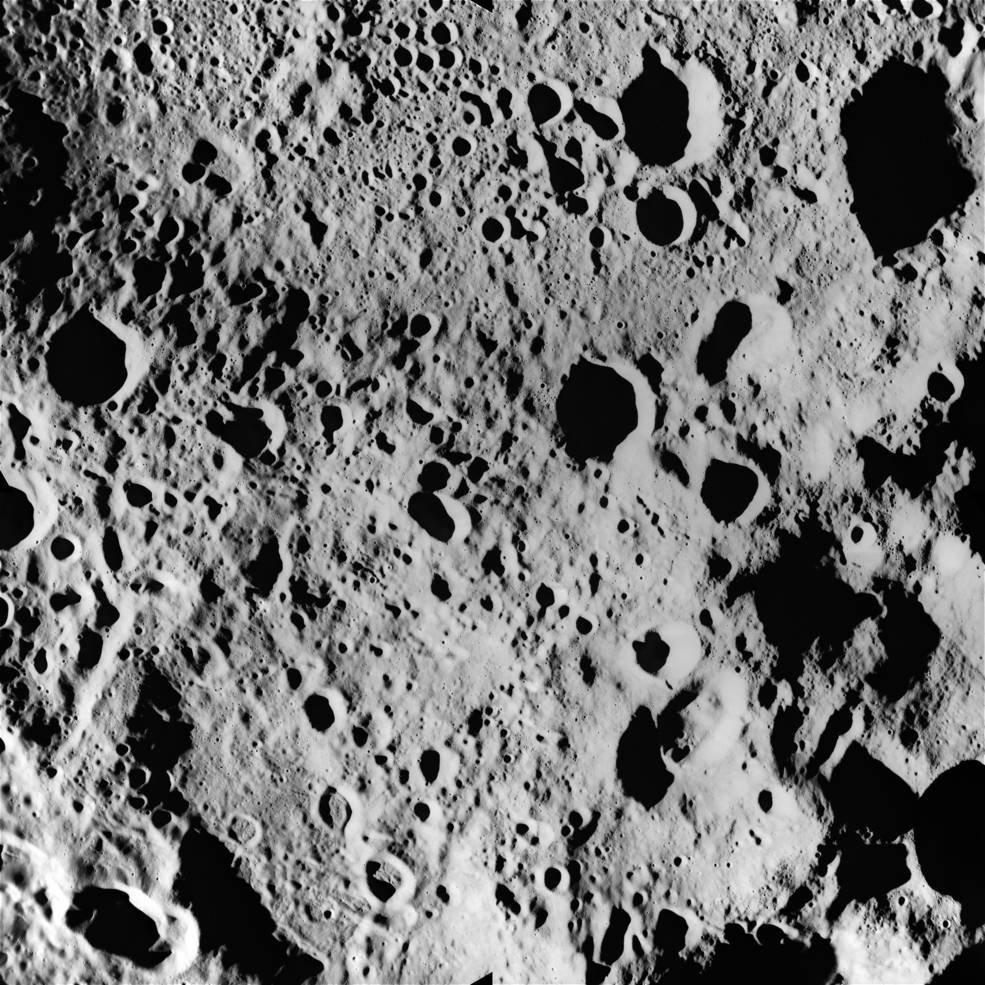

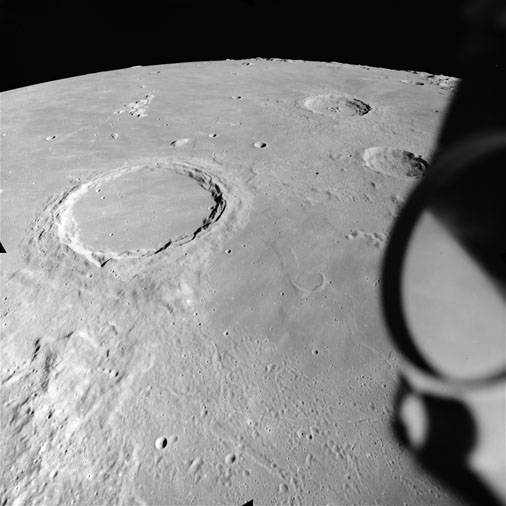

A selection from the hundreds of images Alfred M. Worden took of the Moon during his solo lunar orbital flight. Left: The rim of the farside crater Gagarin. Middle left: The crater Archimedes in Mare Imbrium. Middle right: The crater Lambert, top, and the ghost crater Lambert B at lunar sunrise. Right: The Taurus-Littrow region, the future Apollo 17 landing site.

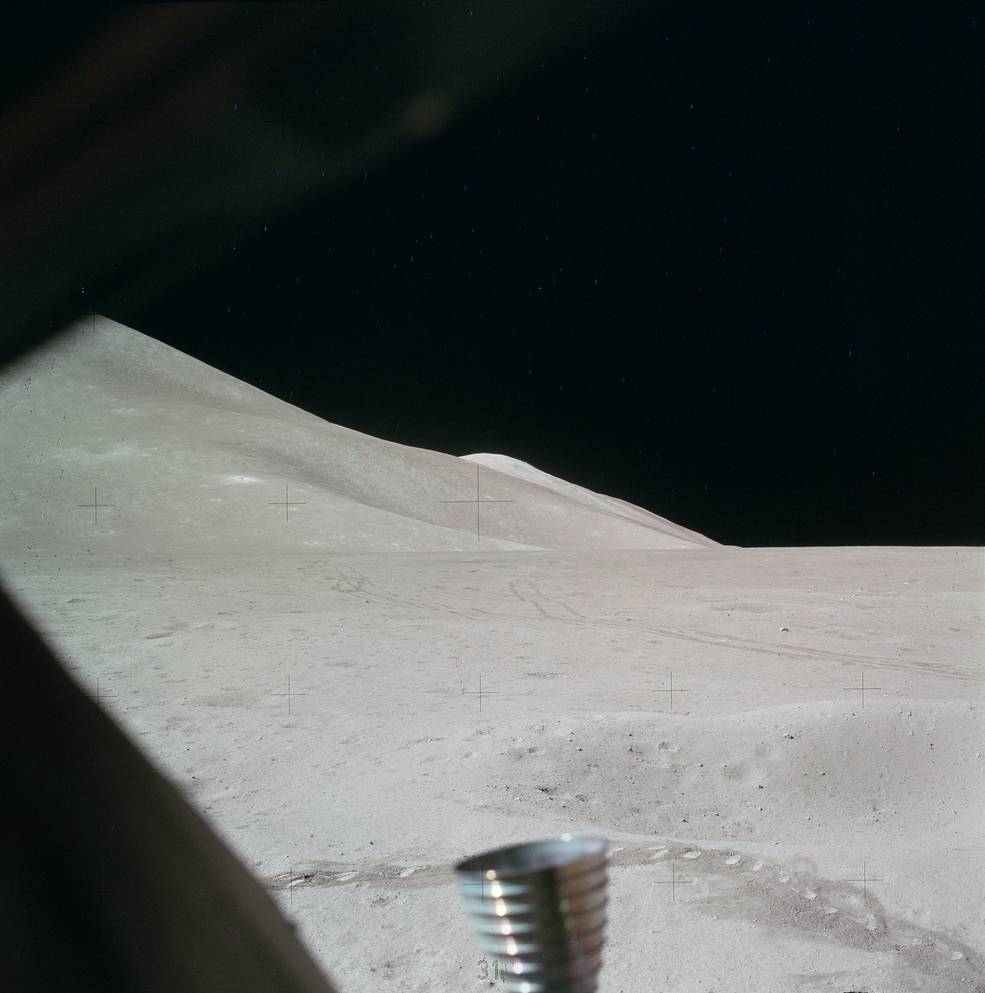

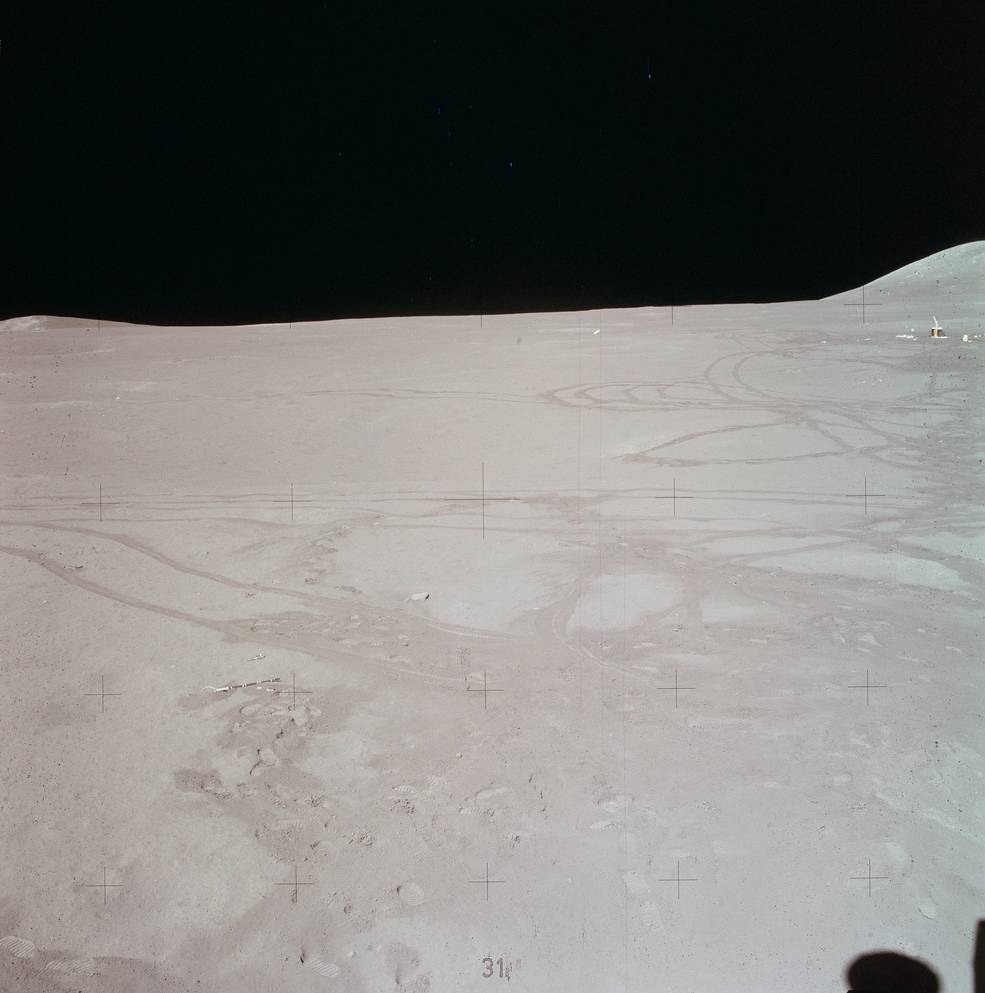

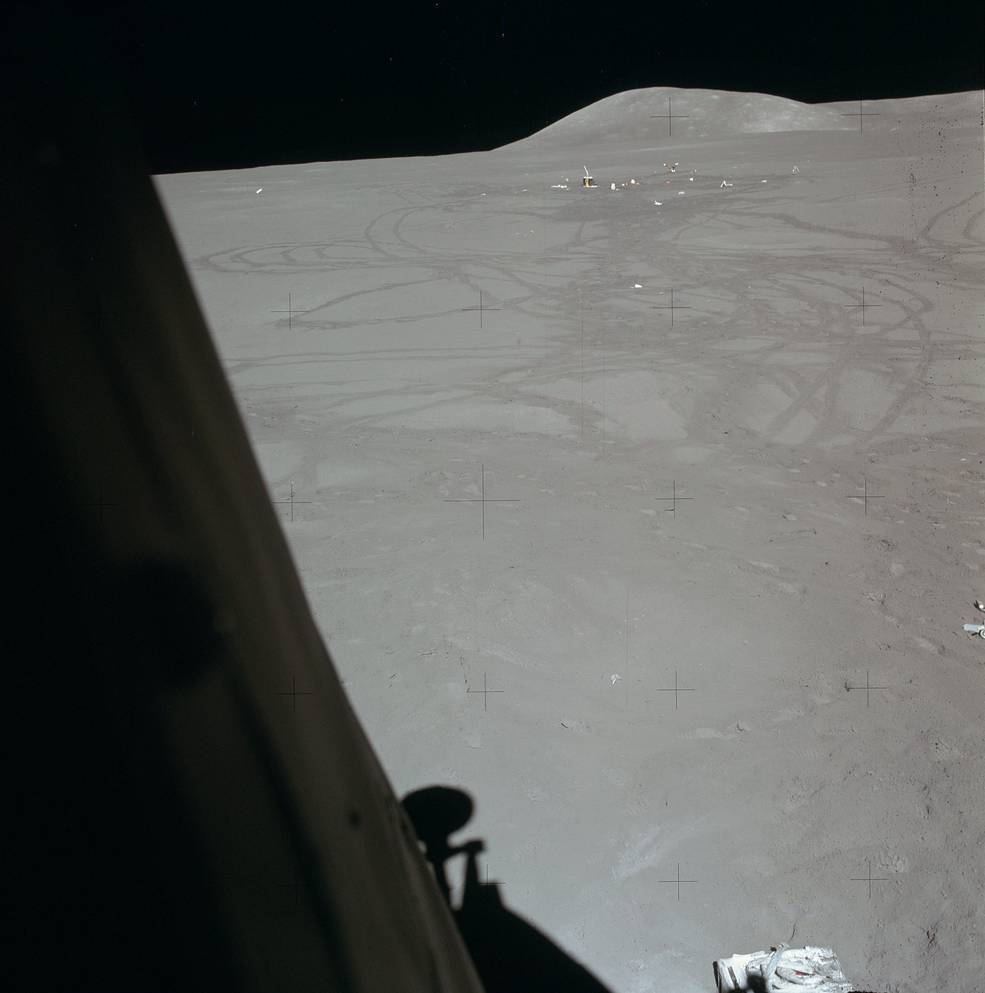

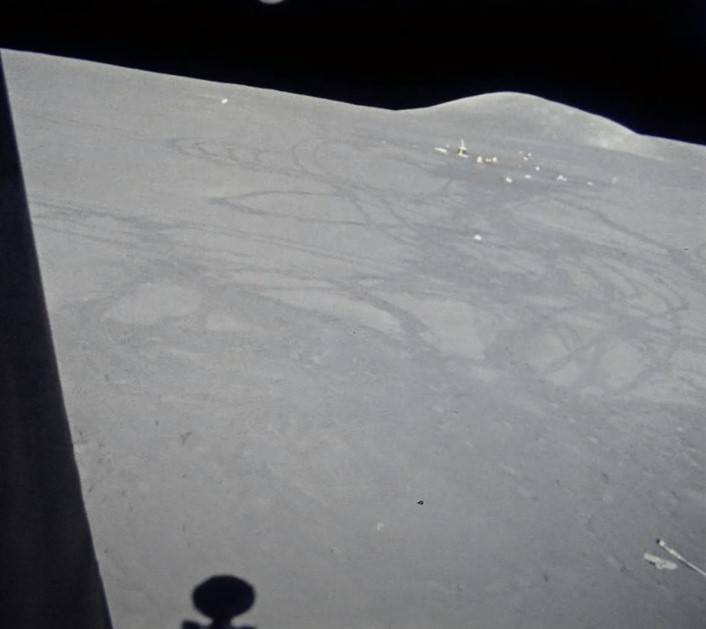

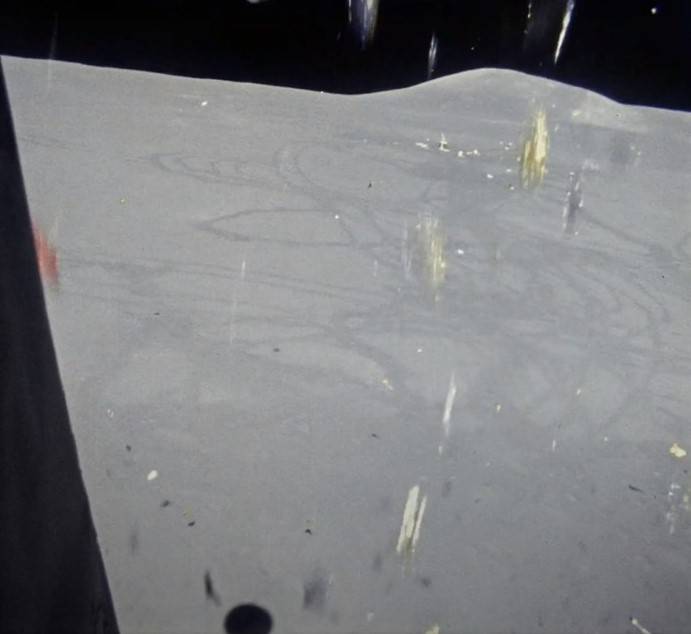

Photographs taken by Apollo 15 astronauts David R. Scott and James B. Irwin from inside the Lunar Module Falcon following their final Moon walk.

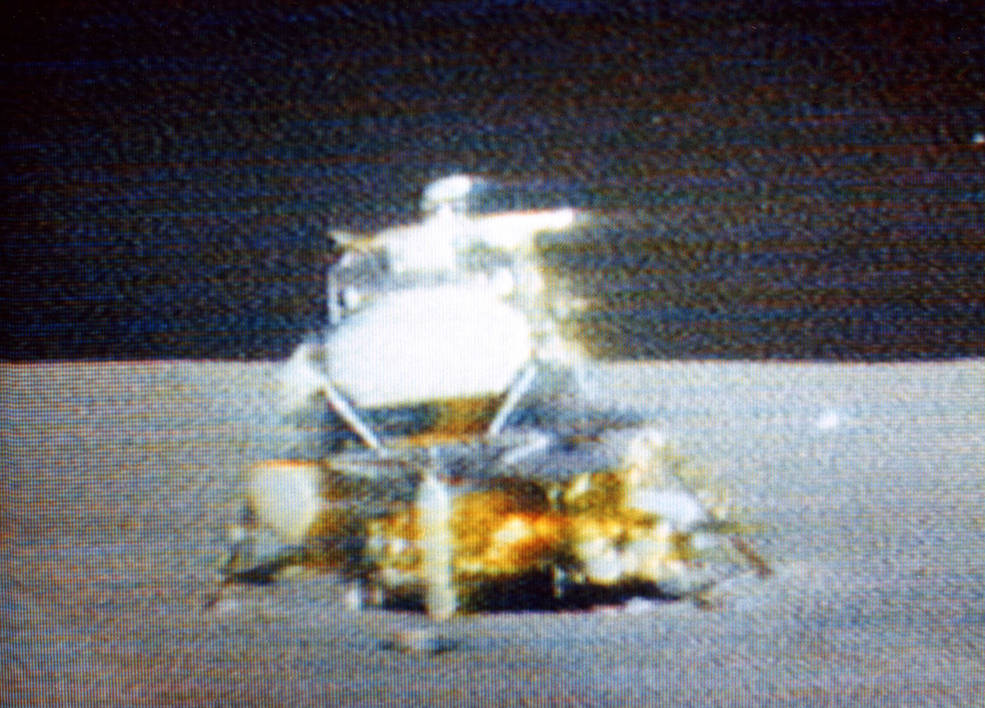

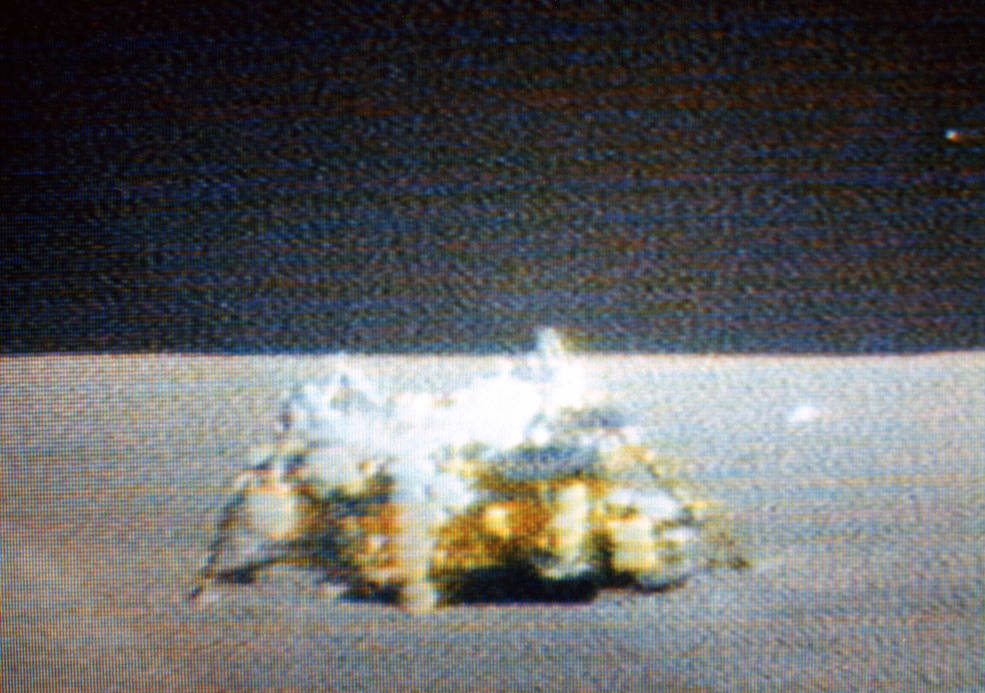

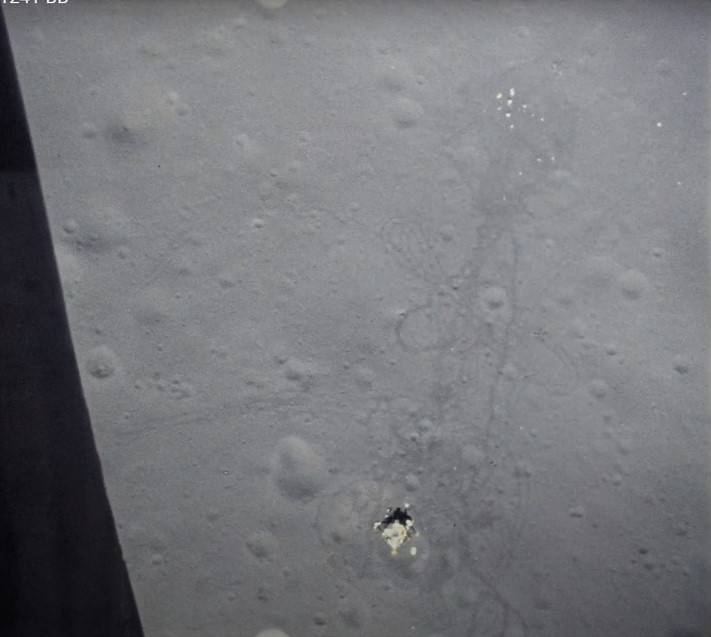

Following three days of exploring the lunar surface at the Hadley-Apennine site, at the end of the third traverse Scott and Irwin reentered the LM for the final time. They removed their backpacks and overboots and jettisoned them out the hatch. They took a series of photographs through the LM’s windows, showing ample evidence of their explorations including footprints, tracks made by the Lunar Roving Vehicle (Rover), and the science instruments they left behind. They repressurized the LM and prepared it for liftoff. This included stowing all the gear – especially the 170 pounds of lunar samples. In Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Flight Director Milton L. Windler and his Maroon Team of controllers, including capsule communicator (capcom) astronaut Edgar D. Mitchell, monitored these activities. During the final stages of liftoff preparations, Worden in Endeavour passed overhead and the three astronauts were able to talk to each other. Less than three hours after entering the LM, Falcon ignited its ascent stage engine and lifted off from the Moon after a then record-setting stay of 66 hours, 55 minutes. For the first time, Mission Control, as well as television viewers on Earth, could watch the liftoff live thanks to the TV camera on the Rover parked about 500 feet away. To underscore the event and to highlight the all-Air Force crew, Worden played a snippet from the U.S. Air Force song, often called “Into the Wild Blue Yonder.”

Still images of the liftoff of the Lunar Module Falcon, broadcast by the television camera aboard the Lunar Roving Vehicle (Rover), parked about 500 feet away.

Still images of the liftoff of the Lunar Module Falcon taken by a movie camera mounted in the spacecraft’s window, at roughly the same times as the sequence above.

View of Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, during the Lunar Module Falcon’s liftoff from the Moon, with capsule communicator Edgar D. Mitchell seated at right in striped shirt.

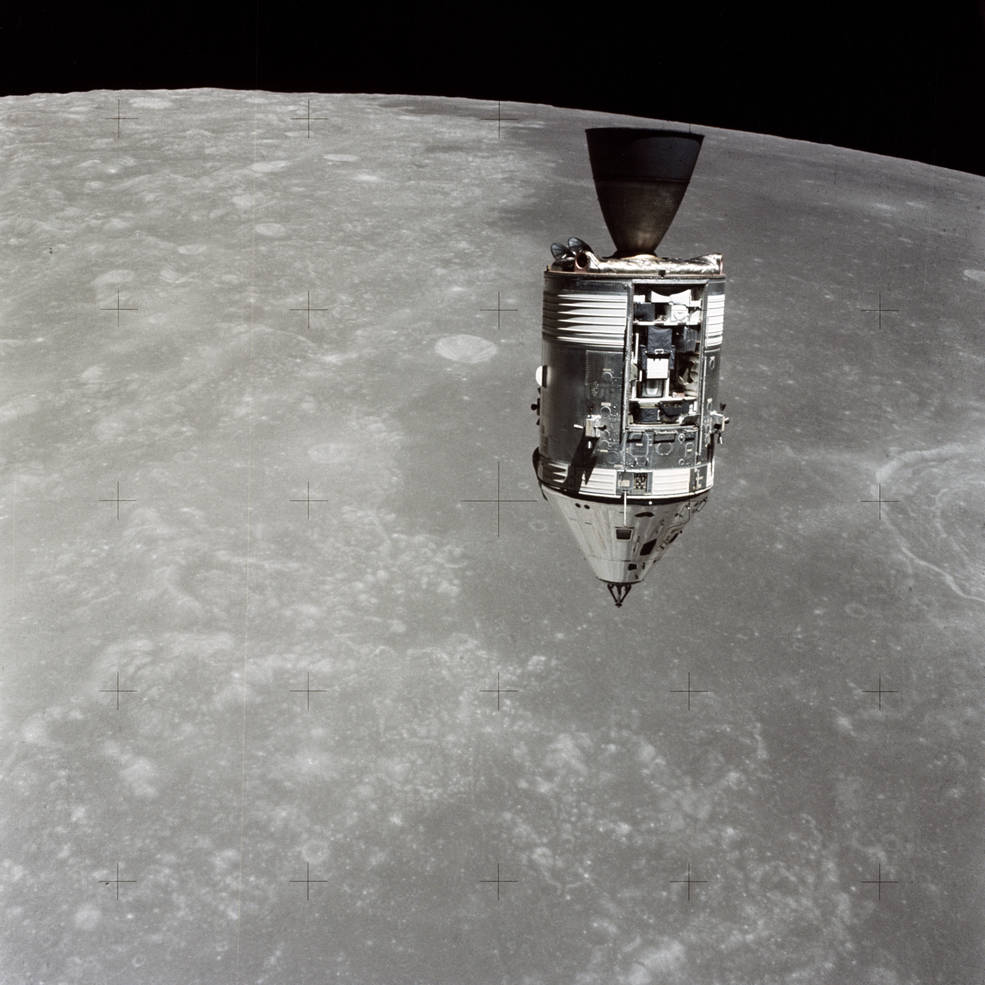

Falcon’s ascent engine burned for 7 minutes 11 seconds, putting the spacecraft into an initial 49-by-10-mile elliptical orbit. Several orbital maneuvers brought Falcon close to Endeavour, on its 49th revolution, and two hours after liftoff from the Moon, the two ships docked in lunar orbit after being separated for nearly 73 hours. The astronauts equalized the pressure between the two spacecraft to open the hatches, and Scott radioed to Houston that “The Falcon is back on its roost and going to sleep,” meaning he and Irwin were powering down the LM. Then the astronauts busied themselves with transferring the rock samples and other gear from Falcon to Endeavour and any unneeded items from Endeavour to be jettisoned with Falcon. Scott and Irwin used a vacuum cleaner to remove as much dust from their suits as possible. During previous missions, the crews removed their suits prior to returning to the CM, but following the deaths of the three Soyuz 11 cosmonauts on June 30, 1971, from a depressurization of their spacecraft after a pyrotechnic separation event, Apollo mission managers decided to be cautious and have the Apollo 15 astronauts wear their spacesuits for the jettisoning of the LM, a maneuver that also involved pyrotechnics. Finally, Scott and Irwin transferred into Endeavour and closed the hatch.

Left: The Command Module Endeavour, with the Scientific Instrument Module bay clearly visible, as seen from the Lunar Module Falcon during the rendezvous. Right: Falcon seen from Endeavour just before docking.

The jettison of the LM ascent stage was delayed by one revolution so the crew could resolve a pressure integrity issue with the CM hatch. Scott reported, “And, it’s away clean, Houston.” Capcom astronaut Robert A.R. Parker replied, “Hope you let her go gently. She was a nice one.” Endeavour fired its thrusters to distance itself from Falcon. After a very long day, the astronauts ate dinner and went to sleep. About 90 minutes after the jettison, Mission Control commanded the LM’s ascent stage engine to fire for 83 seconds until the fuel tanks were empty. This deorbit maneuver caused the ascent stage to impact on the Moon about 25 minutes later some 58 miles from the Apollo 15 landing site. The seismometers at the Apollo 12, 14, and 15 sites recorded the impact.

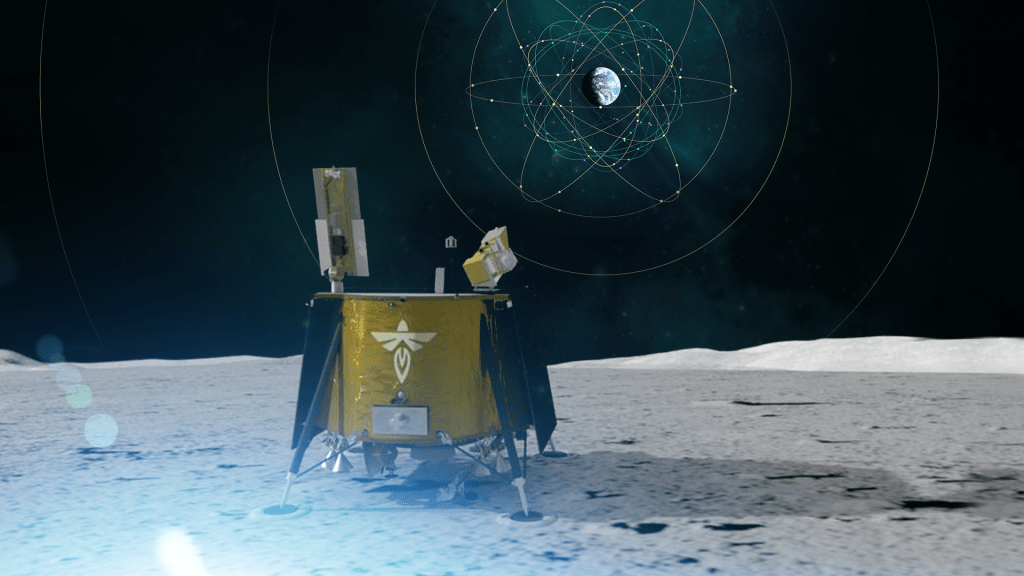

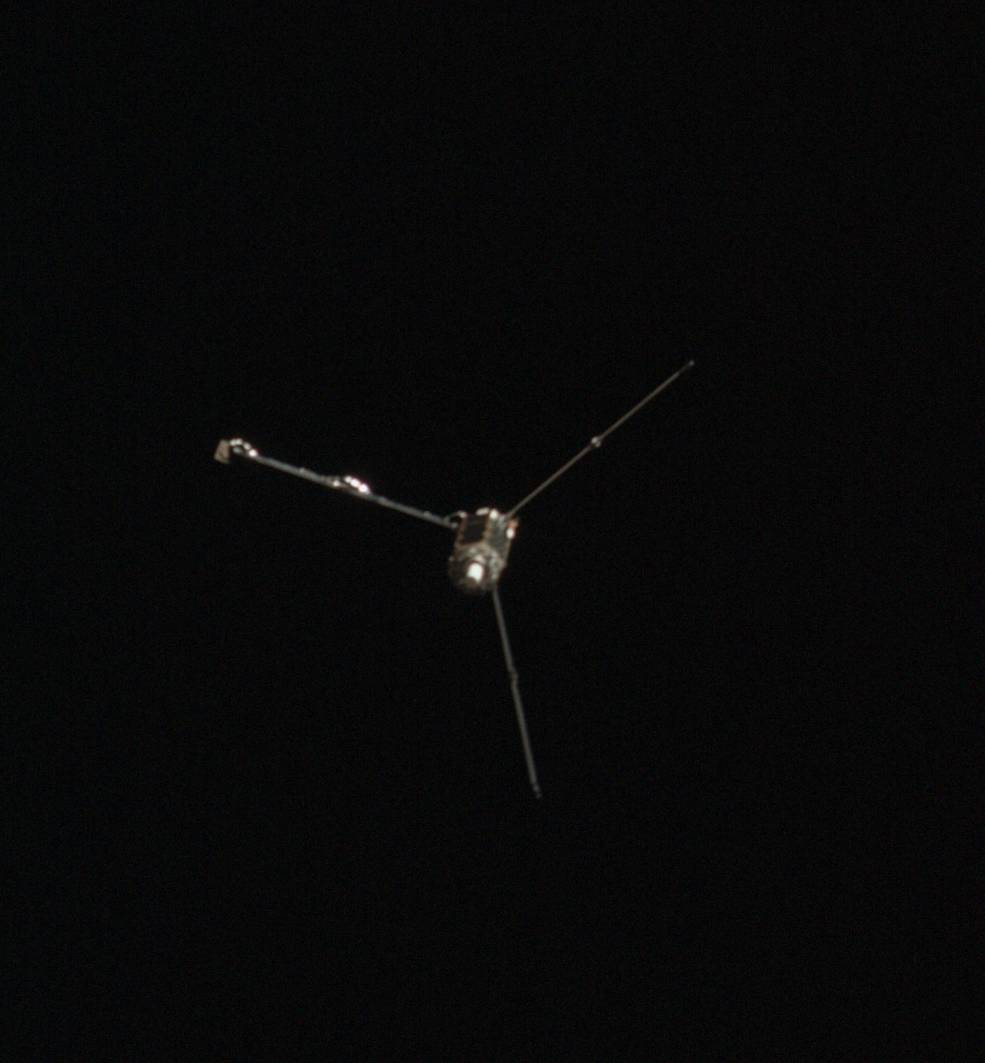

Left: Photograph of the Sea of Tranquility, with the Apollo 11 landing site just below the center of the image. Middle: From lunar orbit, the Earth seen as a thin crescent above the Moon’s surface. Right: The Particle and Fields Subsatellite shortly after its deployment into lunar orbit.

Because the previous day was so lengthy and tiring, Mission Control allowed the astronauts to sleep late, waking them up during the 58th revolution. Through this, their ninth day in space, the astronauts continued with operations of the SIM bay instruments and handheld orbital photography, and repeated the light flash experiment they conducted on the way to the Moon. They went to sleep during their 65th revolution, and after another restful night’s sleep, they awoke to begin their tenth day in space, near the end of their 68th revolution. Capcom astronaut Karl G. Henize played Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” popularized in the soundtrack of the motion picture “2001: A Space Odyssey,” as the wake-up music. The astronauts wrapped up the orbital science activities using the SIM-bay instruments and handheld photography, and on the 73rd revolution they slightly raised their orbit with a short 3.4-second burn of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine. The higher altitude provided an expected one-year orbital lifetime for the 80-pound Particle and Fields Subsatellite that they deployed from the SIM bay into lunar orbit about one hour and 20 minutes later, during their 74th and final orbit around the Moon. Fifty minutes later, Apollo 15 disappeared behind the Moon for the last time, and during this final farside pass ignited the SPS engine for 2 minutes, 21 seconds for the Trans-Earth Injection burn to send them on their way home. Endeavour spent a then record-setting 145 hours, 13 minutes in lunar orbit.

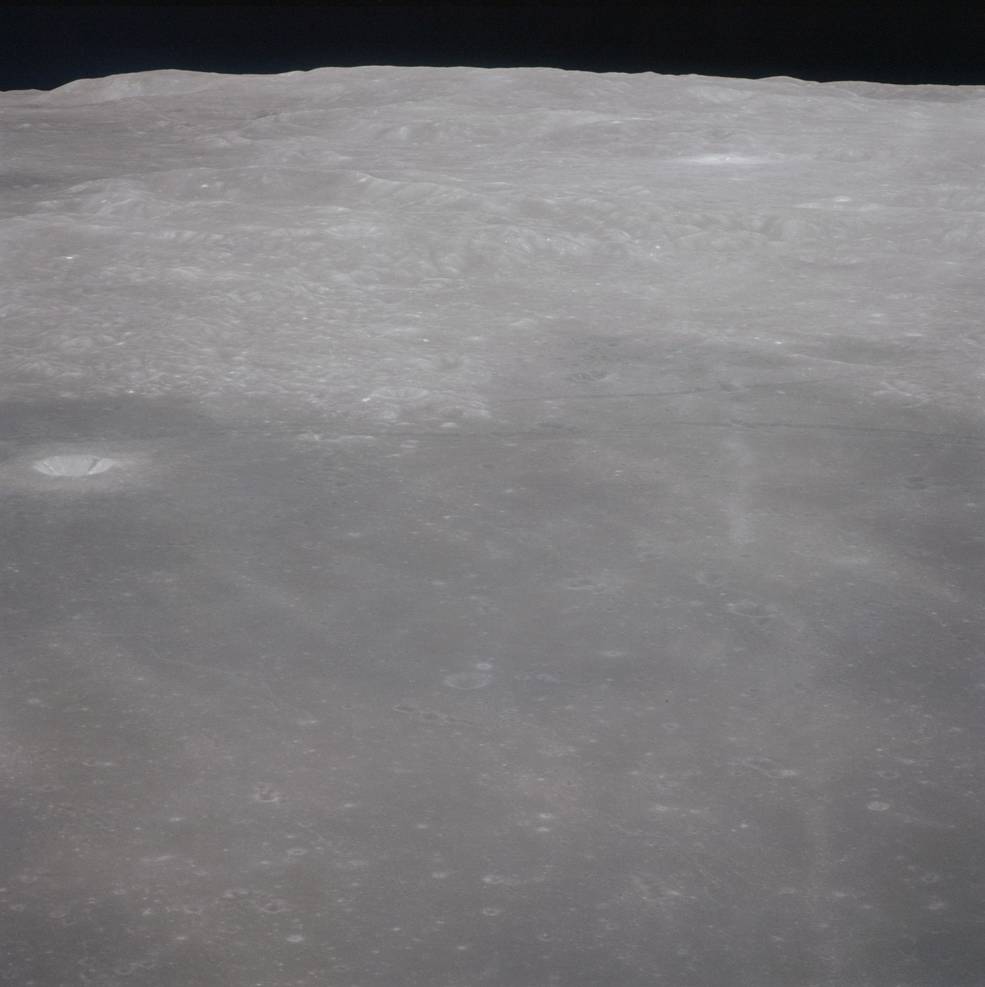

Three images of the receding Moon as Apollo 15 began its journey back to Earth. Left: Looking toward the lunar south pole from 920 miles away. Right: Looking toward the lunar north pole from 2,600 miles away. Right: The full disk from 2,700 miles away.

As Apollo 15 rounded to the nearside of the Moon, Scott radioed to Mission Control, “Hello, Houston. Endeavour’s on the way home.” For the next several hours, the astronauts described the scene of the rapidly shrinking Moon as they sped Earthward. Scott described it as, “Looks like we’re going straight out.” They took a series of photographs of the receding Moon and the SIM bay cameras continued to take images as well. To maintain thermal balance on their spacecraft, they placed it in the Passive Thermal Control, also known as barbecue mode, rotating along its long axis at three rotations per hour. By the time they went to sleep to end their 10th day in space, they had traveled 16,380 miles from the Moon.

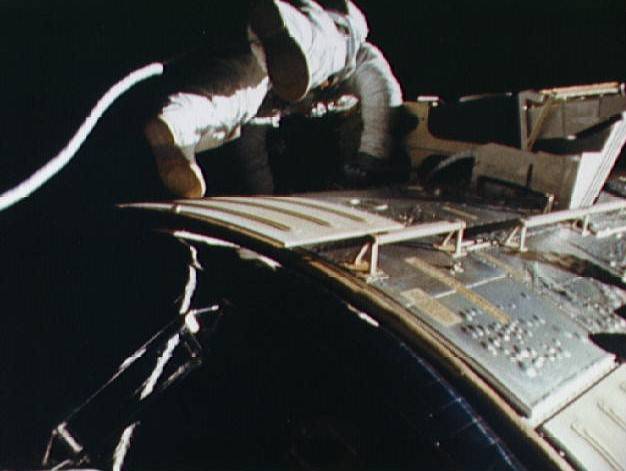

Left: During the cislunar spacewalk, Apollo 15 astronaut Alfred M. Worden translates toward the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay to retrieve film canisters. Right: Worden returning to the Command Module carrying one of the film canisters.

When the astronauts woke up for their 11th day in space, Apollo 15 had traveled more than 30,000 miles from the Moon. And because their trajectory was so precise, capcom astronaut Joseph P. Allen informed them that a planned midcourse correction maneuver that morning was not needed. Three hours after their wake-up call, Apollo 15 passed back into the Earth’s gravitational sphere of influence and began slowly accelerating toward its target, still 57 hours away. In Mission Control, Flight Director Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin’s Gold Team took over from Windler’s Maroon Team, with Henize relieving Allen as capcom. All three astronauts put on their spacesuits in preparation for Worden’s spacewalk to retrieve film canisters from cameras in the SIM bay – the first time a spacewalk was conducted in cislunar space. The entire Apollo 15 backup crew of Richard F. Gordon, Vance D. Brand, and Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt joined Allen at the capcom console to observe the novel event. With Apollo 15 200,000 miles from Earth, Scott depressurized the cabin and opened the side hatch. Worden first discarded two jettison bags filled with unneeded items. A television camera mounted on the open hatch showed Worden exiting the spacecraft and using handholds translate toward the rear of the SIM bay and step into foot restraints to anchor himself. He removed the film canister from the Panoramic Camera and translated back to the hatch, where he handed it to Irwin standing in the open hatch, who handed it to Scott inside the spacecraft. Worden repeated the process for the Mapping Camera canister. On his way back, Worden noted Irwin in the open hatch with the Moon behind him, causing him to comment, “Jim, you look absolutely fantastic against that Moon back there. That is really a most unbelievable, remarkable thing.” His tasks completed, Worden reentered the CM and closed the hatch. Scott repressurized the cabin and all three removed their spacesuits. The spacewalk lasted 39 minutes. For the remainder of the day, the astronauts busied themselves with photography and science experiments. By the time they went to sleep, they had closed the distance to Earth to about 174,000 miles.

Left: Image of the Moon as it nears totality during the lunar eclipse. Middle: Apollo 15 astronauts David R. Scott, left, Alfred M. Worden, and James B. Irwin during the televised news conference. Right: Still image from the television downlink of the Moon coming out of totality.

On Aug. 6, when Scott, Worden, and Irwin awoke for their 12th and last full day in space, the distance to Earth had decreased to 152,000 miles and their velocity continued to increase. During the night, Apollo 15 became the longest Apollo mission to that time, surpassing the Apollo 7 record of 10 days, 20 hours, and 9 minutes. For the day’s wakeup call, capcom Allen greeted the all-Air Force crew with “Anchors Aweigh,” the U.S. Navy’s unofficial song, perhaps as a reminder that in just over a day, the CM Endeavour, itself named after a sailing ship, will be bobbing in the Pacific Ocean. He informed them that their trajectory was still so accurate that a planned course correction maneuver that day was not required. The astronauts continued with science experiments, including another run of the light flash experiment. They observed a total lunar eclipse from their unique vantage point. As the eclipse neared totality, they held a televised news conference, with capcom Henize reading the questions from reporters to the astronauts, sporting 12-day-old beards. Near the end of the news conference, they mounted the TV camera in a spacecraft window, providing an excellent view of the Moon as it came out of the eclipse. They completed stowing all items in the spacecraft in preparation for the next day’s splashdown. When Scott, Worden, and Irwin went to sleep for the last time in space, the Earth was just 100,000 miles away and approaching rapidly.

To be continued…

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center