After Apollo 14 entered lunar orbit on Feb. 4, 1971, astronauts Alan B. Shepard, and Edgar D. Mitchell separated their Lunar Module Antares from the Command Module Kitty Hawk, aboard which Stuart A. Roosa remained in orbit. Shepard and Mitchell touched down in the Fra Mauro highlands region and conducted two lunar surface excursions lasting more than nine hours in total. They set up an experiment package and collected 93 pounds of rock and soil samples to return to waiting scientists on Earth. In the meantime, Roosa conducted observations and photography of the lunar surface from orbit. After their 33-hour lunar surface stay, Shepard and Mitchell rejoined Roosa in orbit, and, their mission accomplished, left lunar orbit for the three-day return trip to Earth.

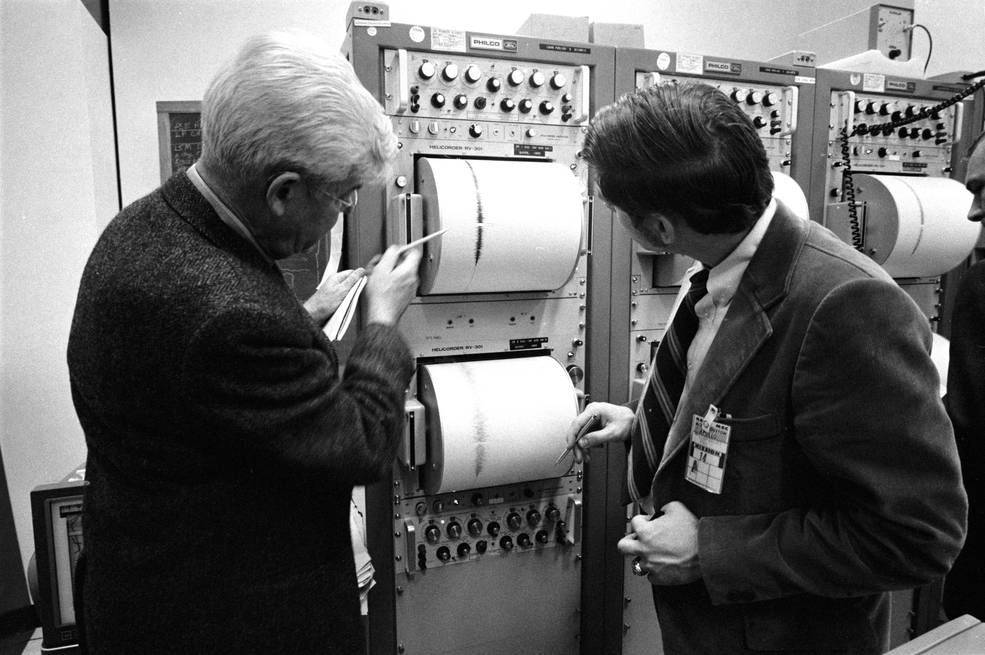

Left: In the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, with Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin at the flight director console and the seismometer tracings resulting from the intentional crash of the Apollo 14 Saturn V rocket’s third stage on the Moon displayed on the large screen in the background. Right: In an MCC support room, Maurice Ewing, director of the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory at Columbia University in New York, left, and Columbia University graduate student David Lammlein examine the seismometer tracings resulting from the crash of the Saturn V rocket’s upper stage on the Moon.

Following the Jan. 31, 1971 launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Apollo 14’s translunar coast lasted 79.5 hours. During the astronauts’ fourth day in space, their spacecraft’s trajectory took them past the leading edge of the Moon, and as they disappeared behind it, as expected, all contact with the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, was cut off. Thirty minutes later, the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine fired for more than six minutes to drop them into an elliptical 195-by-67-mile orbit around the Moon. As they rounded to the near side of the Moon, Shepard reported to capsule communicator (capcom) Fred W. Haise in the MCC that “we had an extremely fine burn.” He added enthusiastically, “Well, this really is a wild place up here. It has all of the grays, browns, whites, dark craters that everyone’s talked about before. It’s really quite a sight. … Really fantastic.” Mitchell added his first impressions of the Moon, “the description that comes to mind … is that it looks like it’s been molded out of plaster of Paris.” Roosa provided a running commentary of all the landmarks as they passed over them. Haise informed them that their Saturn V rocket’s expended third stage impacted on the Moon as expected. About 100 miles away, the seismometer left by the Apollo 12 astronauts picked up the impact, with the Moon reverberating for more than three hours.

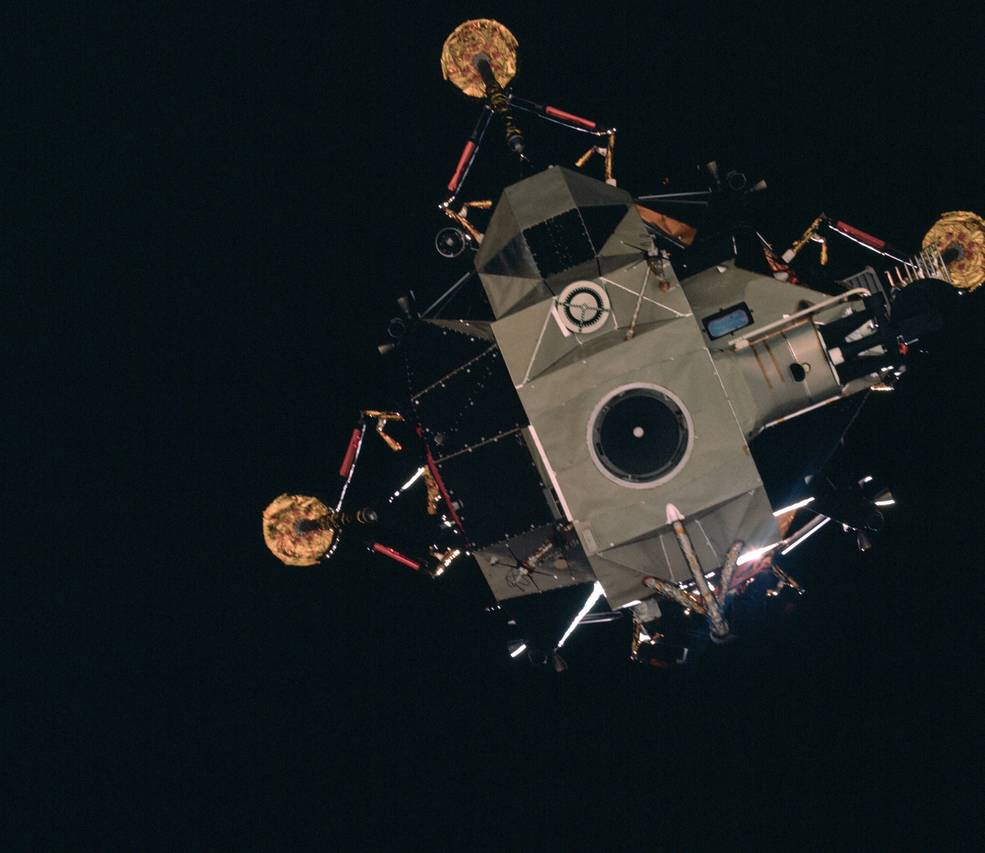

Left: The Apollo 14 Command and Service Module Kitty Hawk photographed in lunar orbit by astronauts Alan B. Shepard and Edgar D. Mitchell shortly after they separated aboard the Lunar Module Antares. Right: Antares photographed from Kitty Hawk by Stuart A. Roosa shortly after undocking.

Flight Director M.P. “Pete” Frank and his controllers known as the Orange Team took over the consoles in the MCC from Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin’s Gold Team, with NASA astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton replacing Haise as capcom. About 4 hours after entering lunar orbit, the astronauts fired the SPS engine for 21 seconds to change their orbit to one 67 miles by 10 miles, a procedure used for the first time on Apollo 14. By using the large SPS engine to reduce the low point of their orbit, the Lunar Module (LM) retained additional fuel margin for the descent to and landing on more rugged terrain than attempted on previous missions. Settled in their new orbit, the crew began their fourth sleep period of the mission.

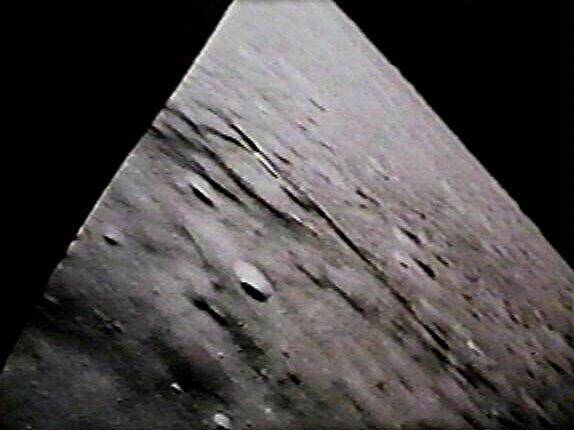

Left: Photo of the Earth rising against the lunar landscape taken from aboard the Apollo 14 Lunar Module (LM) Antares before beginning the descent to the surface. Middle: A still image from a 16 mm film taken from the LM’s right hand window during the descent to the surface, showing Cone Crater just to the left of the center. Right: A still from the 16 mm film showing one of the Triplet Craters, a landmark near the touchdown point.

The fifth day included the critical landing on the Moon. The astronauts put on their spacesuits, and Shepard and Mitchell transferred into the LM Antares to activate its systems, including deploying its landing gear. They closed the hatches, leaving Roosa alone in the CM Kitty Hawk to conduct observations from orbit while Shepard and Mitchell explored the surface. As they came around to the Moon’s front side on their 12th revolution, the two spacecraft undocked. Roosa fired the SPS engine to put Kitty Hawk back into a circular 60-mile high orbit. Meanwhile, Antares passed over the Fra Mauro landing site on the 13th revolution, and Shepard called out that they could easily pick out landmarks for their descent and landing. Overcoming an issue with their guidance computer that threatened to cancel the landing, Shepard and Mitchell began Antares’ powered descent to the surface on the 14th revolution. In an ironic twist, capcom Haise, the astronaut who, but for the oxygen tank explosion during Apollo 13, would have landed at Fra Mauro the previous year, gave Apollo 14 the “go” to initiate the powered descent to that very site. The LM’s landing radar set in the incorrect setting gave some initial concern, but the descent then continued trouble-free. Shepard brought Antares to a soft landing with about 60 seconds of fuel remaining. The LM settled on a seven-degree slope, well within the range the vehicle could handle.

Three images taken shortly after Apollo 14’s landing at Fra Mauro. Left: Photo taken from the Lunar Module (LM) Antares’ left hand window, with the LM’s thrusters partially visible. Right: Image taken from the LM’s right hand window, with streaking on the surface caused by the descent engine’s exhaust visible. Right: Image from the right hand window, partially showing the LM’s thrusters.

Controllers evaluated the status of Antares after the landing, and cleared it to stay on the surface. Shepard and Mitchell turned off all the descent stage systems. They photographed the lunar surface through their respective windows, the slope of their landing site readily apparent. Providing commentary on their surroundings, Mitchell suggested that “there is more terrain, more relief here, than we anticipated from looking at the maps.” To which Shepard punned, referring to the successful landing, “There’s a hell of a lot of relief inside the cabin!” The two grabbed a meal and began preparations for the first of their two moonwalks on the lunar surface.

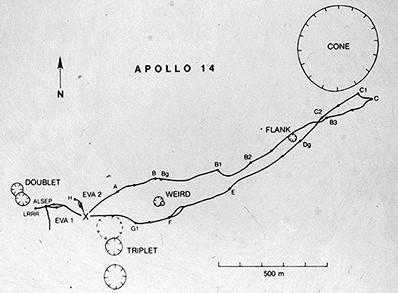

Schematic map of the Apollo 14 landing site, showing the short first excursion west of the Lunar Module Antares (marked by X) to set up the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package and the longer trek east to Cone Crater and back.

Left: At the start of the first moonwalk, Alan B. Shepard on the Lunar Module Antares’ footpad about to take his first steps on the lunar surface. Middle: Shepard on the lunar surface, photographed by Edgar D. Mitchell still inside Antares. Right: Mitchell coming down the ladder to join Shepard on the surface.

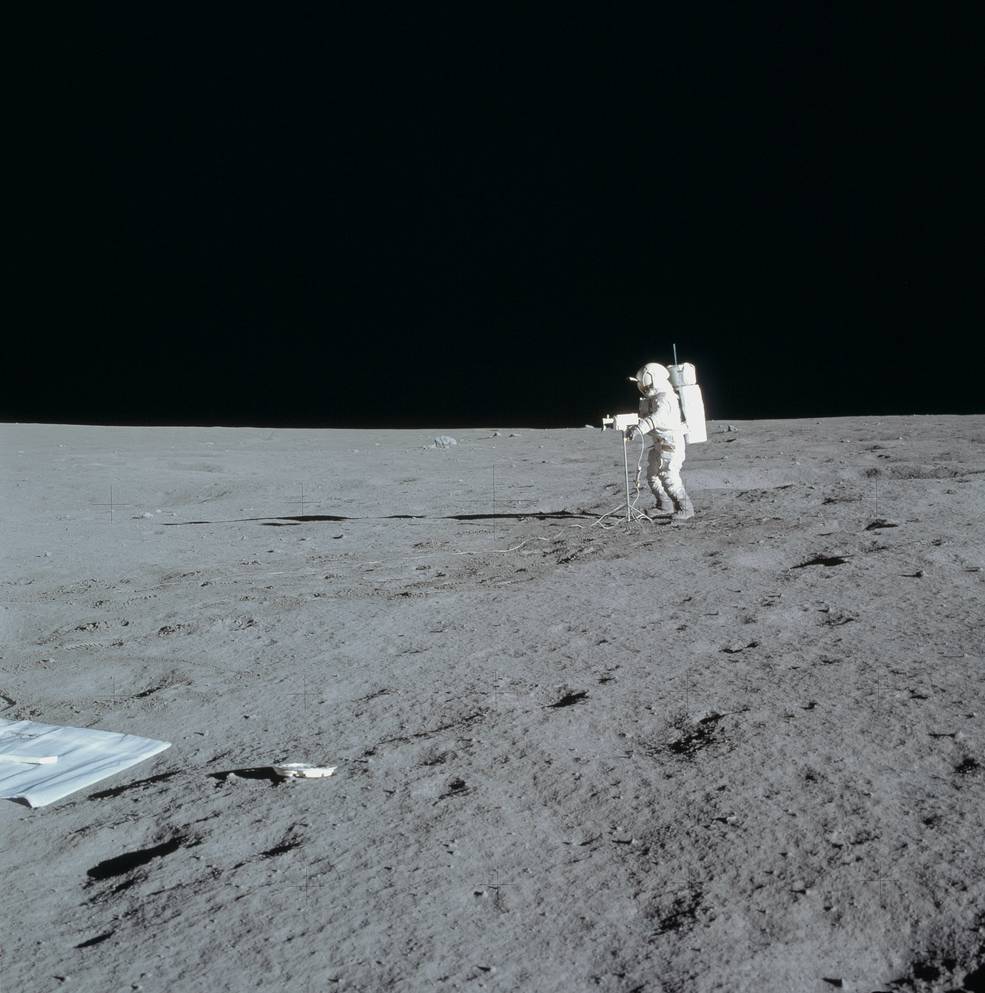

About five hours after landing, they depressurized the LM and Shepard climbed down the ladder, activating a TV camera on the side of the vehicle. The world watched him jump down from the ladder and step onto the lunar surface, becoming the fifth person to walk on the Moon. Referring to Shepard’s age of 47, at the time considered advanced for an astronaut, capcom Bruce McCandless quipped, “Not bad for an old man!” Referring to his 10-year wait to return to space after his historic Mercury-Redstone 3 flight in May 1961, Shepard replied, “And it’s been a long way, but we’re here.” Mitchell joined him on the surface five minutes later. Shepard removed the Modular Equipment Transporter (MET), a two-wheeled cart to carry their equipment, from its stowage position on the LM and placed it on one of the footpads for later use. He removed the camera from the LM and set it up on a tripod so controllers in the MCC and viewers around the world could follow their activities. Mitchell collected a contingency sample, gathered in case they had to make an emergency liftoff from the Moon. To improve communications with Earth, Shepard set up the S-band dish antenna.

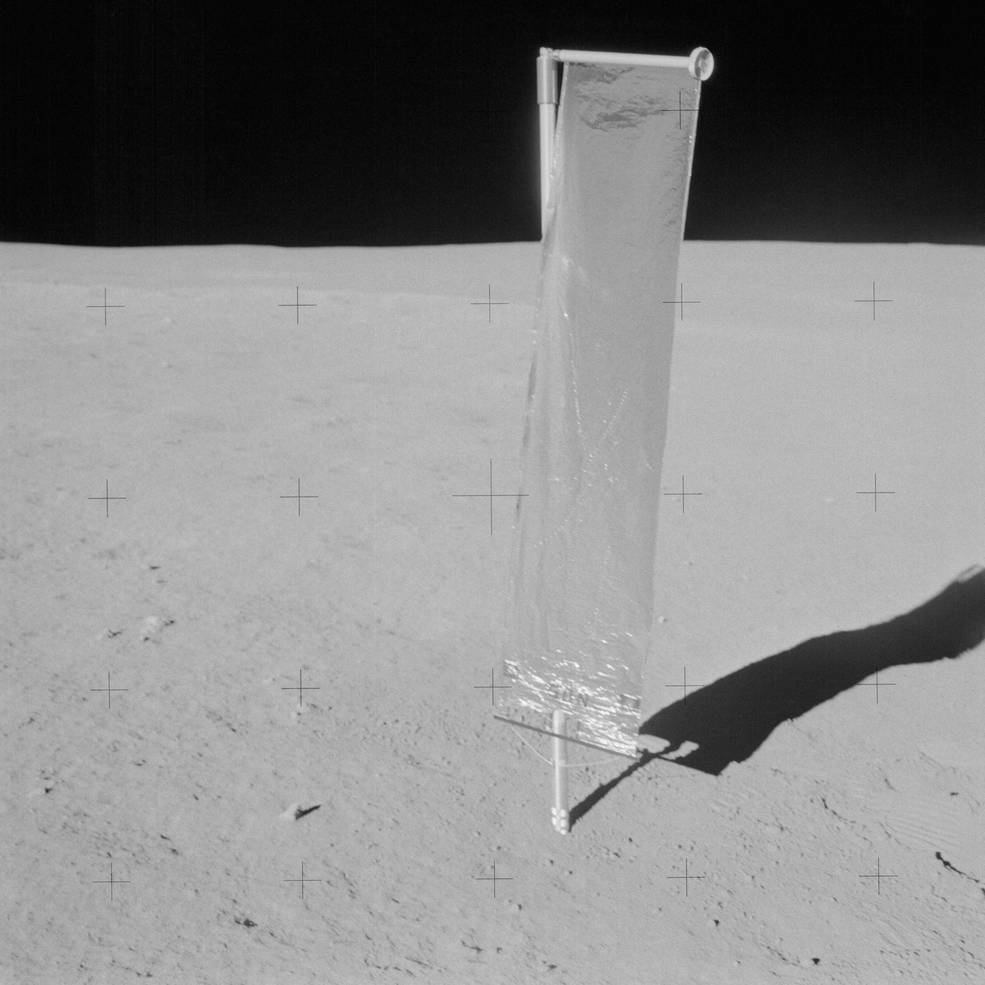

Left: During their first moonwalk, Alan B. Shepard and Edgar D. Mitchell deployed the S-band antenna to aid communications with Earth; they have temporarily positioned the Modular Equipment Transporter, still wrapped in its insulation, on one of Antares’ footpads. Middle: The deployed Solar Wind Composition experiment. Right: Mitchell conducting a panoramic tour with the television camera.

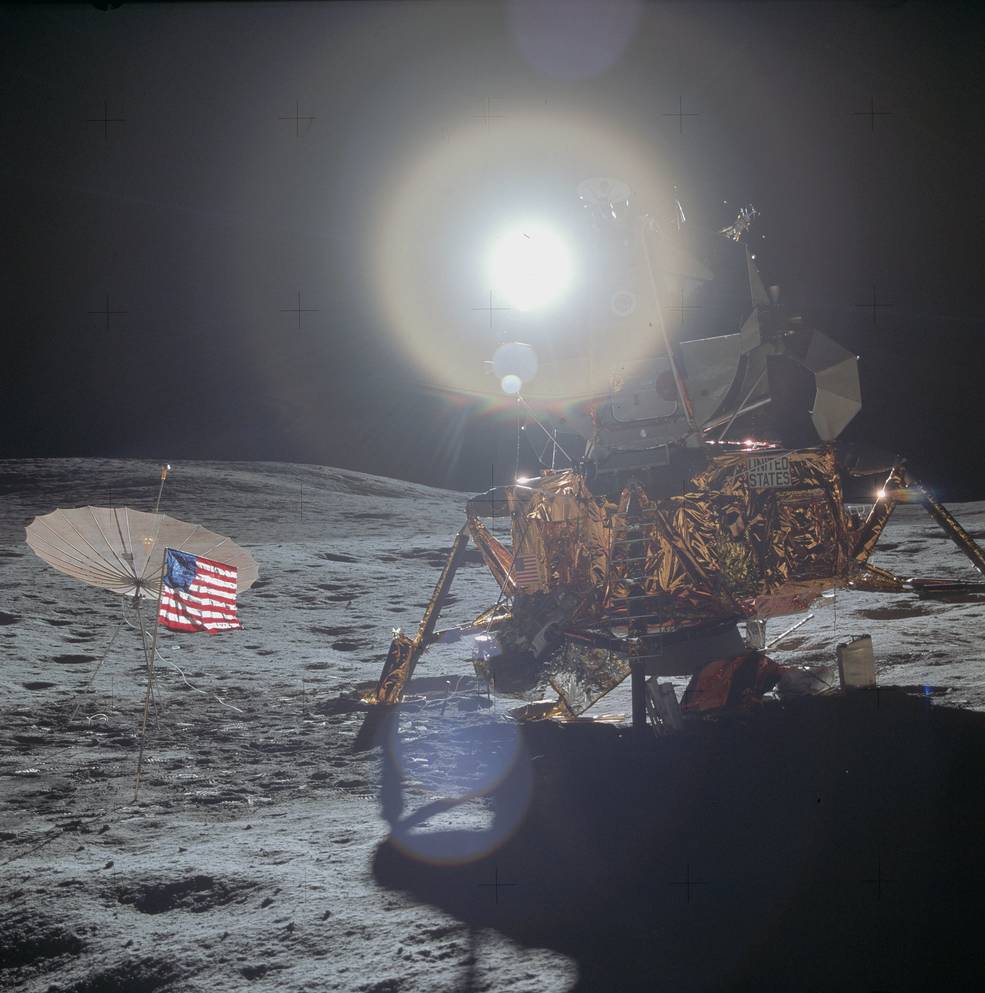

The primary focus of the first moonwalk involved setting up the surface experiments. These included the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP) and several independent investigations. Mitchell deployed the Solar Wind Composition (SWC) experiment that he later retrieved at the end of the second moonwalk for return to Earth. They planted the American flag and took turns photographing each other with it, and then photographed their surroundings and the LM itself to document its condition.

Left: Apollo 14 astronaut Alan B. Shepard with the American flag. Middle: Edgar D. Mitchell with the American flag. Right: The Lunar Module Antares on the lunar surface at the Fra Mauro site.

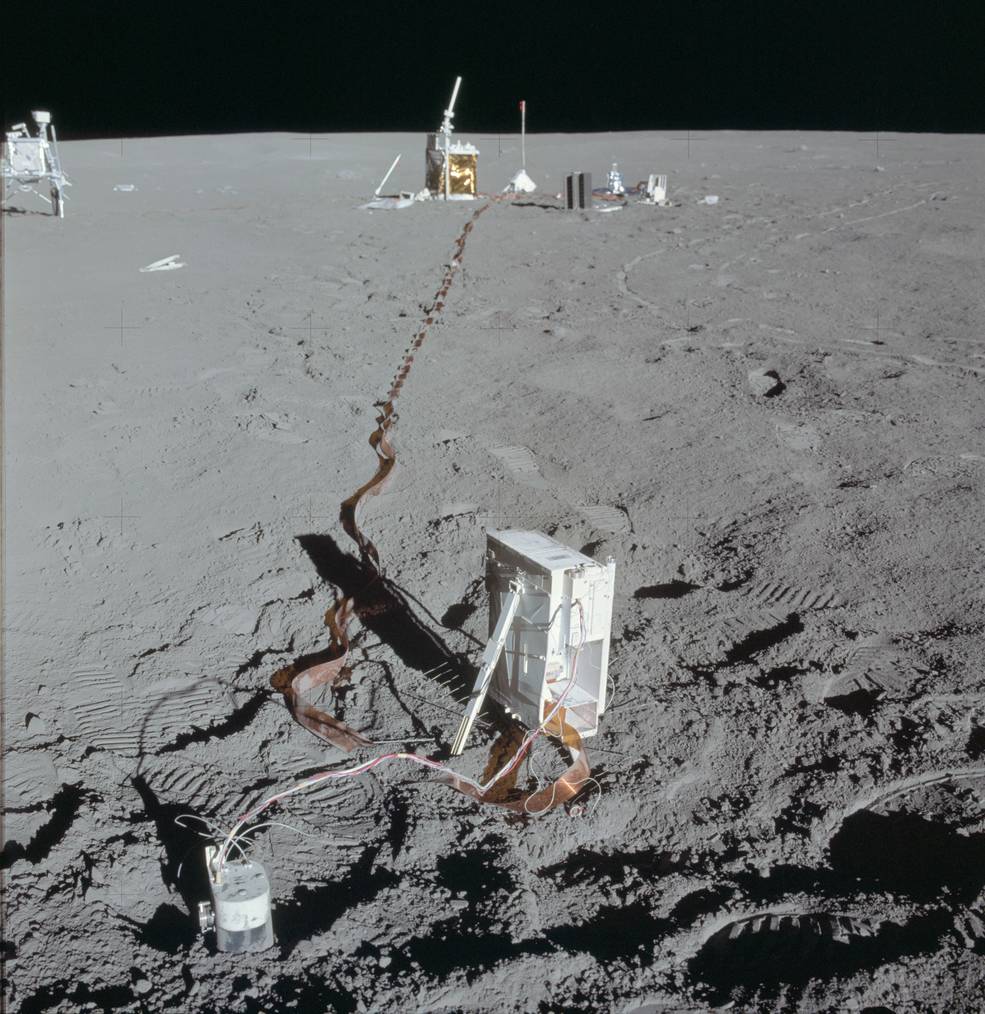

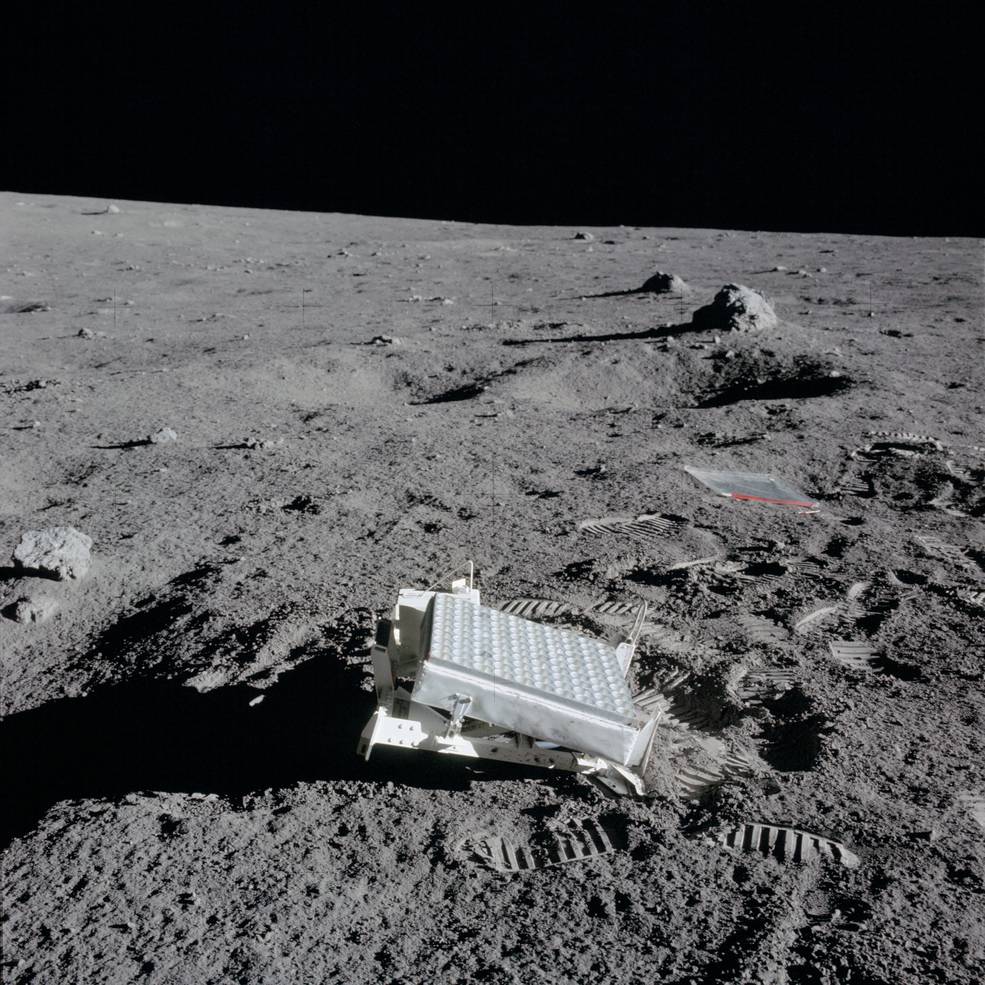

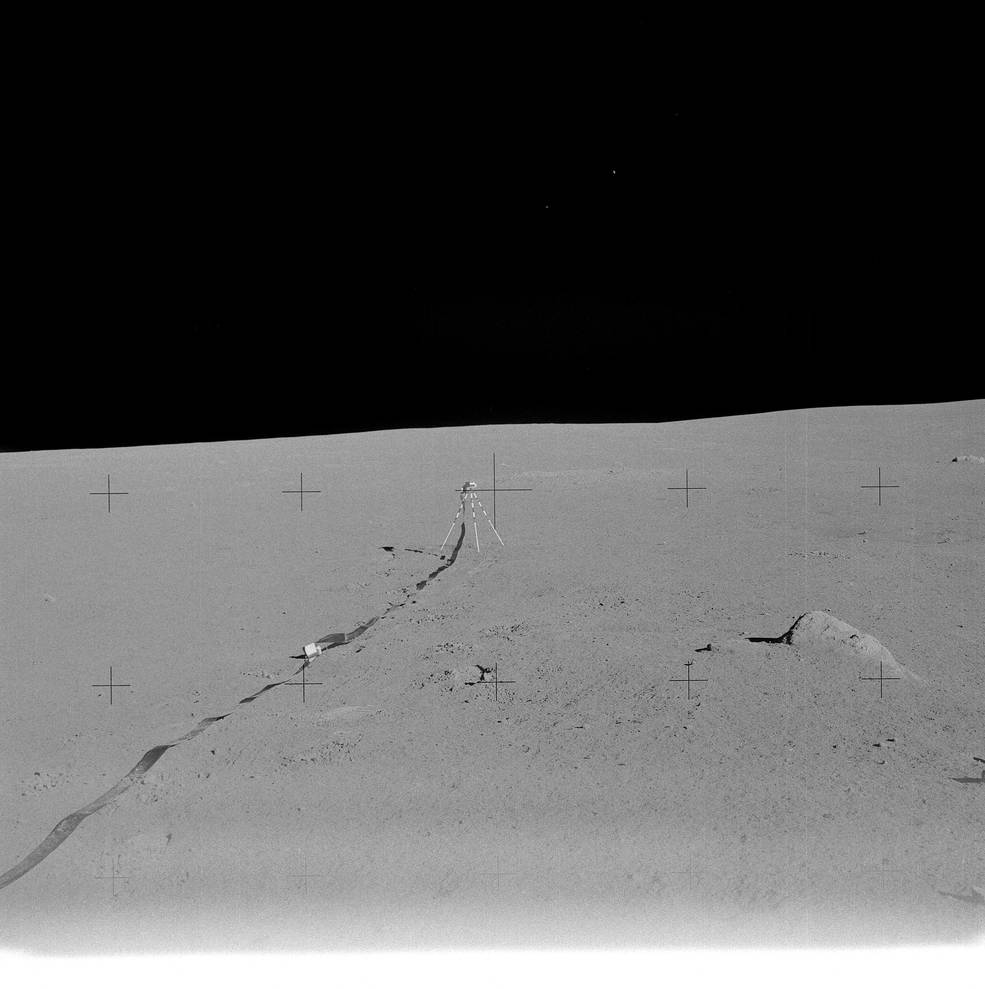

Shepard deployed the MET for their first traverse. The two retrieved the two ALSEP sub-packages from their stowage location in the side of the LM descent stage, with Mitchell retrieving the plutonium-containing cask used to power the ALSEP’s radioisotope thermal generator. They loaded some of the experiments on the MET and attached others to a barbell-like carrying device. With Shepard pulling the MET and Mitchell carrying the barbell, they set out toward the west to find a suitable flat location to set up the ALSEP experiments about 600 feet from the LM, and the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector 100 feet west of the ALSEP. The two spent the next hour and 40 minutes deploying the various ALSEP instruments, including an active seismology experiment that fired small explosive charges into the surface with geophones that recorded the resulting shock waves. Mitchell spent 48 minutes conducting this experiment that provided important clues about the Moon’s interior structure. On the way back to the LM, Shepard collected geology samples, including a football-sized rock. Back at the LM, they packed up their samples, dusted each other off, and headed back up the ladder and inside the spacecraft. They spent 4 hours and 48 minutes outside on their first moonwalk.

Three views from the television downlink during the first Apollo 14 moonwalk. Left: Edgar D. Mitchell, left, carrying part of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP) and Alan B. Shepard pulling the Modular Equipment Transporter as they begin their walk to deploy the experiments. Middle: Shepard, left, and Mitchell traverse a depression on their way to the ALSEP deploy site. Right: Mitchell, left, and Shepard have arrived at the ALSEP deployment site, about 600 feet west of the Lunar Module Antares.

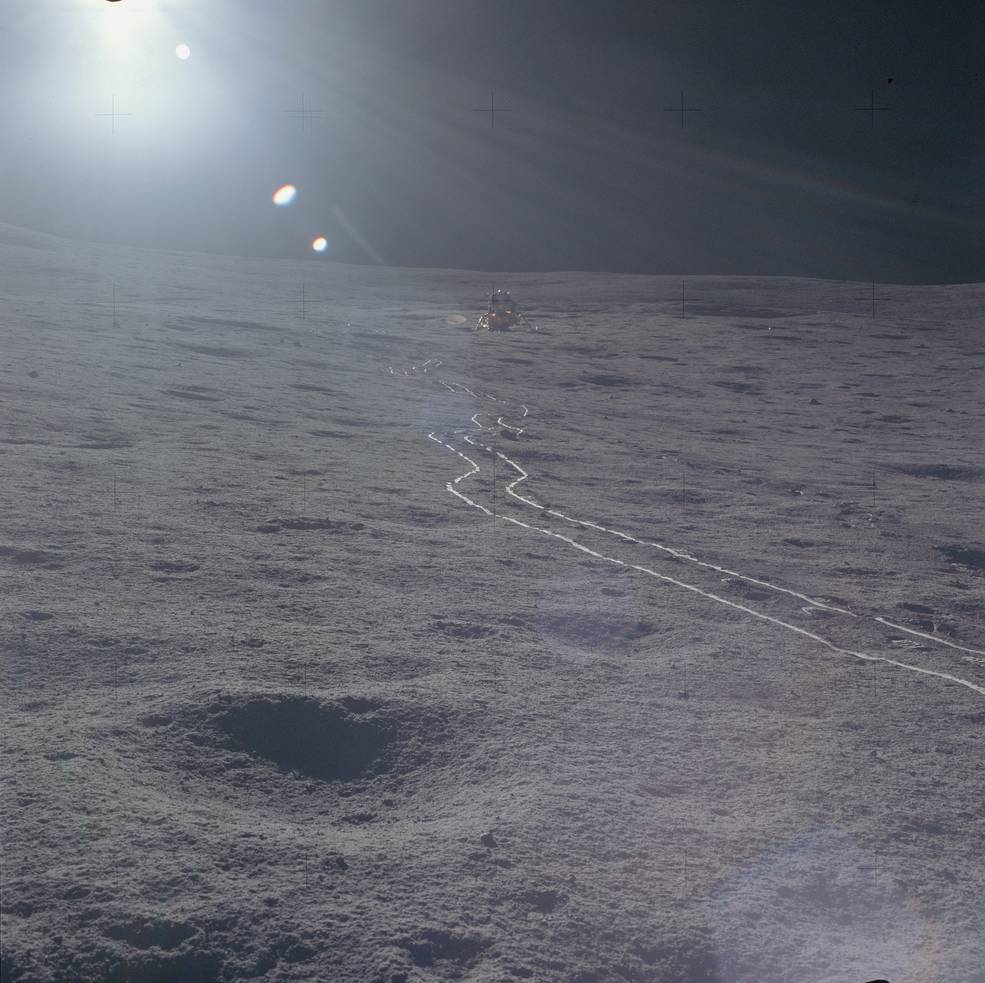

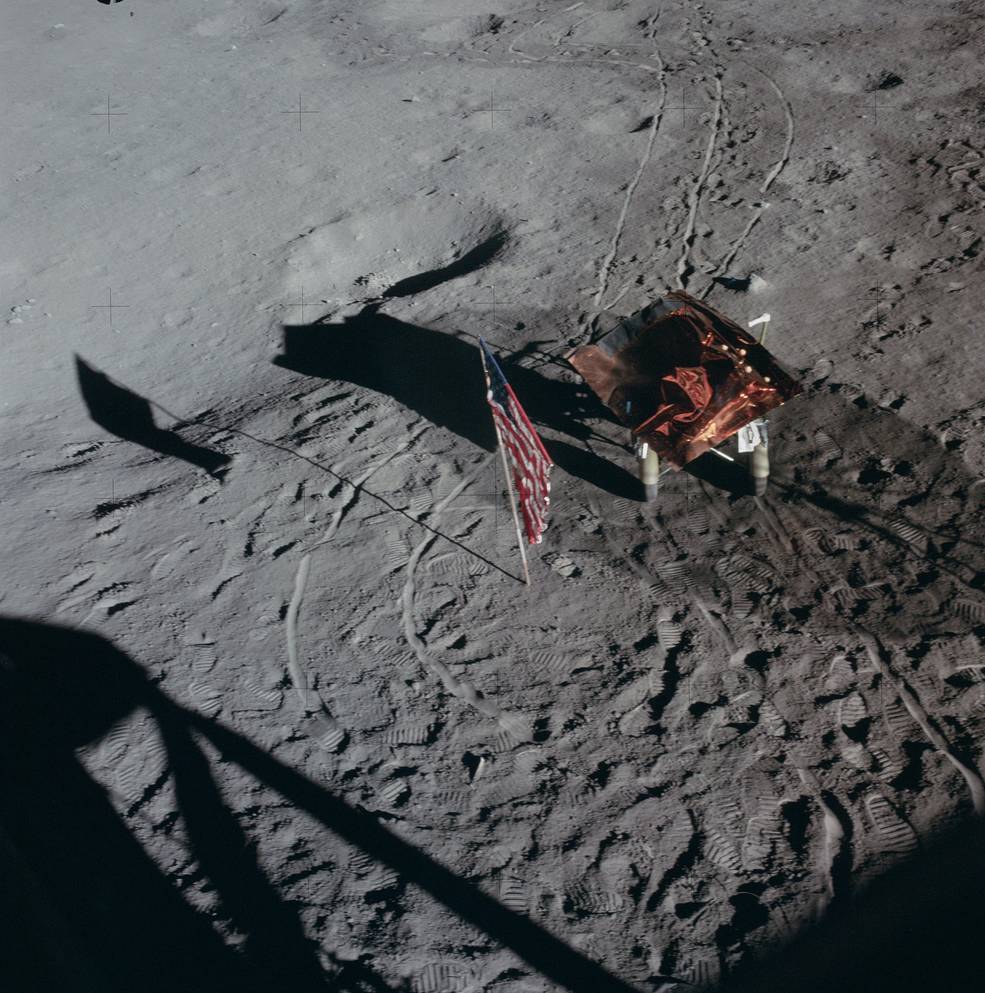

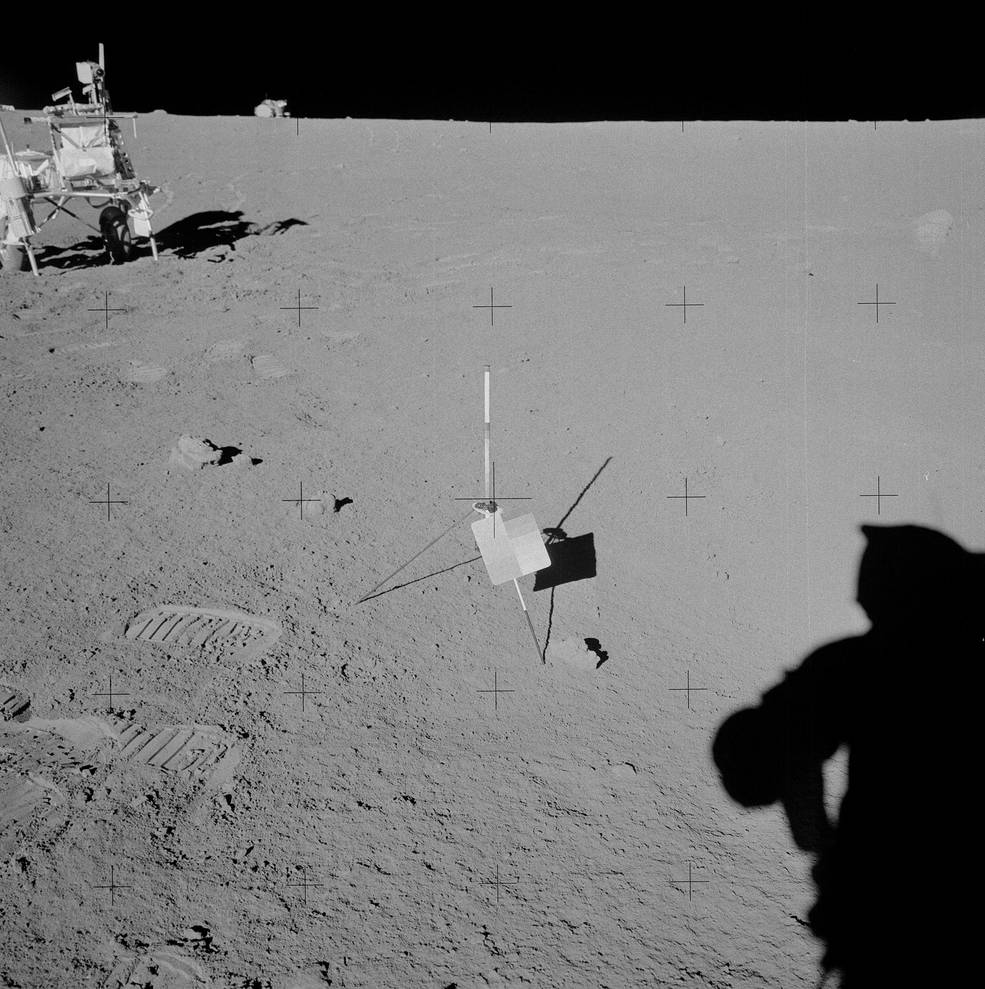

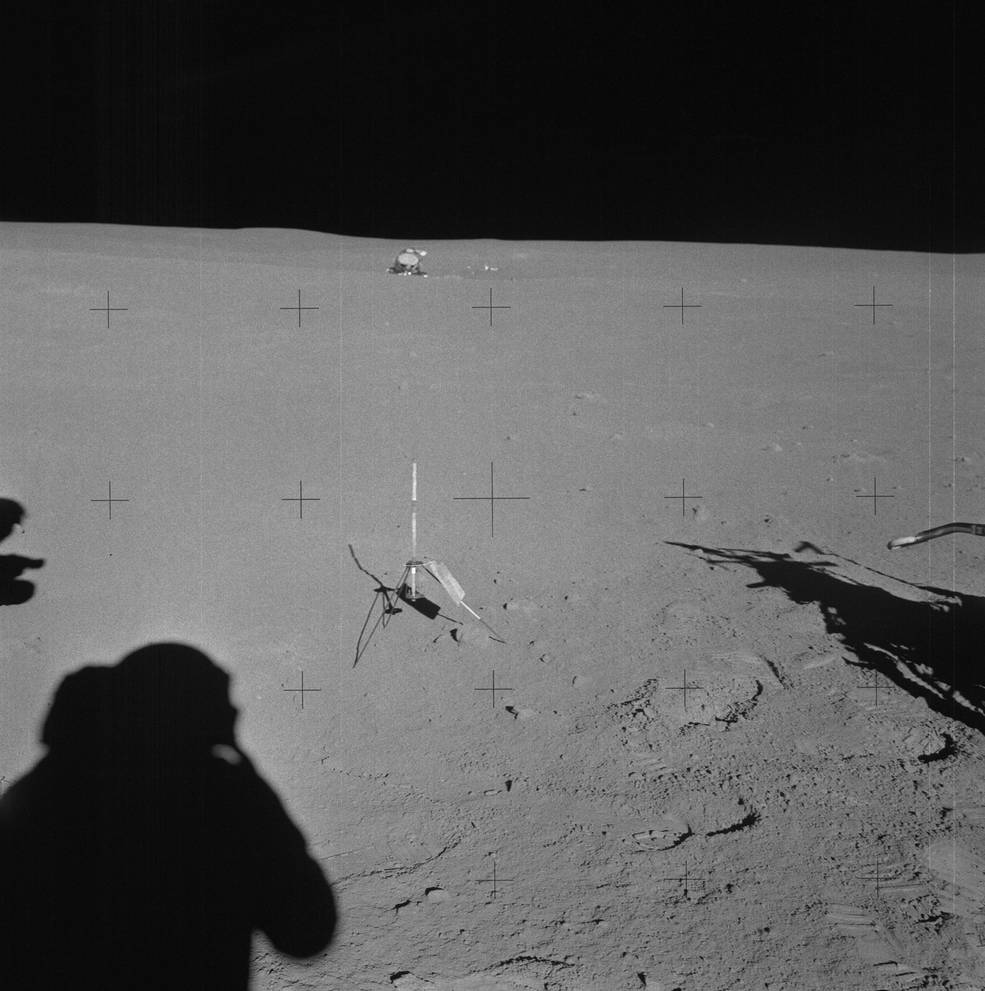

Left: Overall view of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP) set up about 600 feet west of the Lunar Module (LM) Antares. Middle: The Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector experiment set up about 100 feet west of the ALSEP. Right: View of the LM Antares, looking east from the ALSEP site and showing the tracks left by the Modular Equipment Transporter.

Left: A still image from 16 mm film showing Edgar D. Mitchell, left, holding the “thumper” device during setup of the active seismometer experiment, with Alan B. Shepard behind the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP). Middle: Mitchell at the end of 300-foot geophone line, part of the active seismometer experiment. Right: Shepard has drawn a circle in the lunar dust to mark the comprehensive sample collection site, looking back toward the ALSEP as Mitchell approaches.

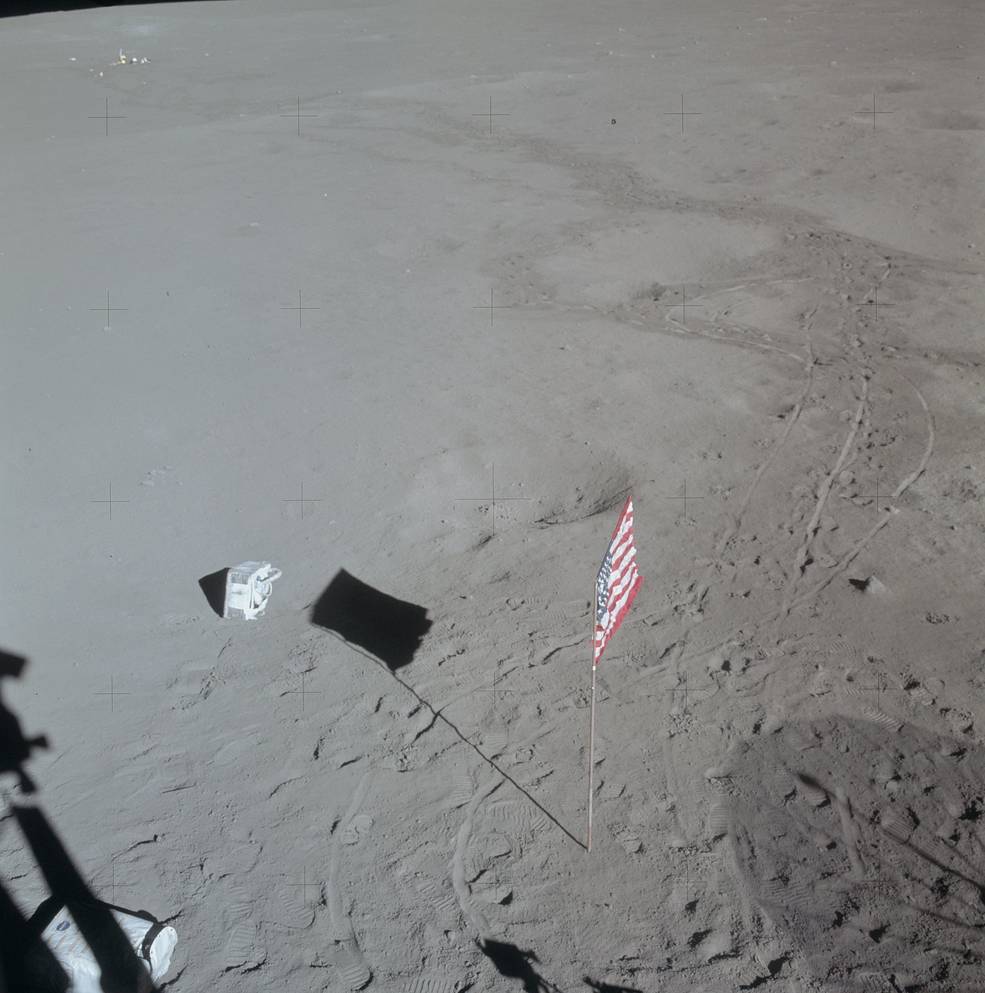

Left: Alan B. Shepard has drawn a circle in the lunar dust to mark the comprehensive sample collection site looking toward Lunar Module (LM) Antares. Middle: Documentary photograph of the football-sized rock from the comprehensive sample collection site. Right: View from LM’s right hand window after the first moonwalk showing the American flag and the Modular Equipment Transporter covered with a thermal blanket and parked in the shade of the S-band antenna.

After repressurizing the LM, Shepard and Mitchell reconditioned their spacesuits, ate dinner, strung up their hammocks, and went to sleep. Both crewmembers managed about four to four-and-a-half hours of sleep, and awoke early to begin preparations for the second moonwalk, whose main objective was the nearly 1 mile trek to Cone Crater. Geologists hoped that samples collected from near the crater’s rim, likely material from deeper layers ejected during the crater’s formation, would reveal insights about the Moon’s interior. The astronauts put their helmets and gloves back on, depressurized the LM, and as before, Shepard headed out first, followed three minutes later by Mitchell. They loaded their equipment and sample collection bags onto the MET and headed east toward Cone Crater. Along the way, they used the Lunar Portable Magnetometer to measure the Moon’s very weak magnetic field and stopped to collect rock and soil samples at predetermined sites.

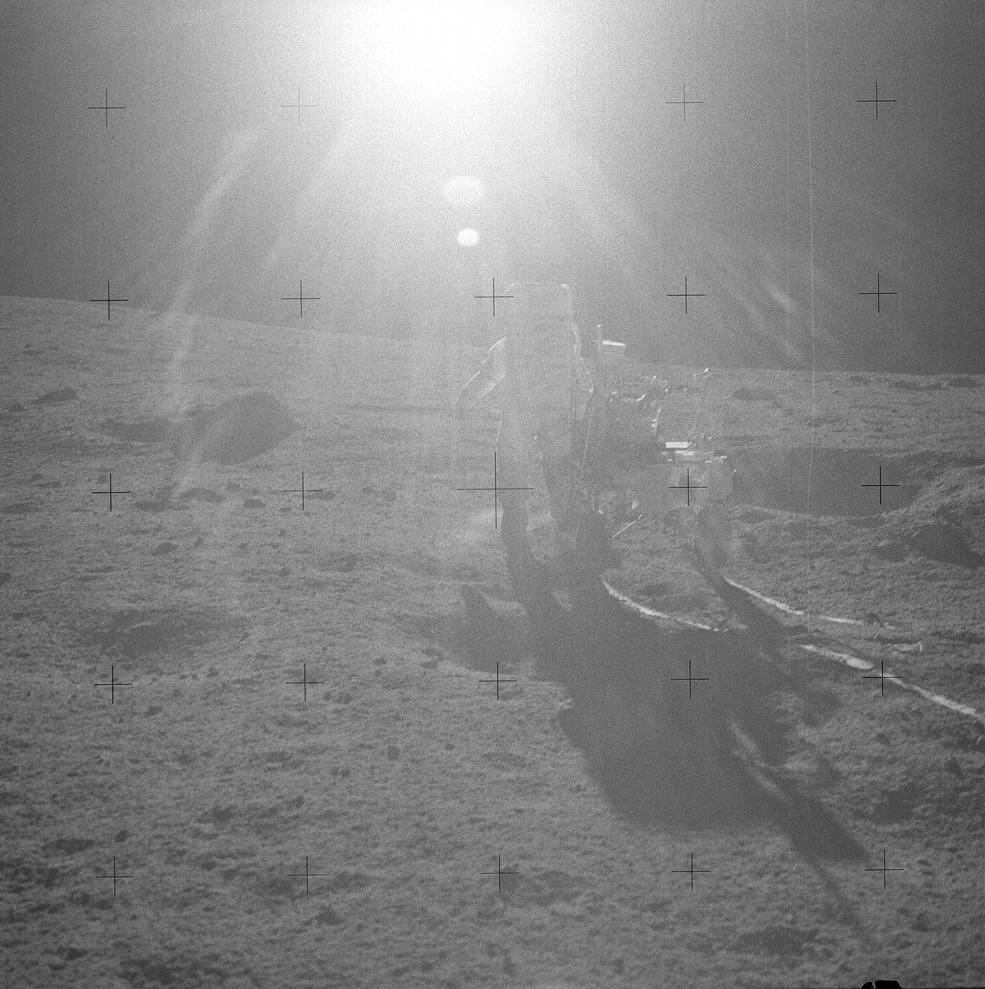

Still images from the Apollo 14 television downlink during the second moonwalk. Left: Alan B. Shepard preparing the Modular Equipment Transporter (MET) at the start of the second moonwalk. Right: Shepard, left, and Edgar D. Mitchell with the MET about to begin their trek east toward Cone Crater, with Sun glare in the television camera.

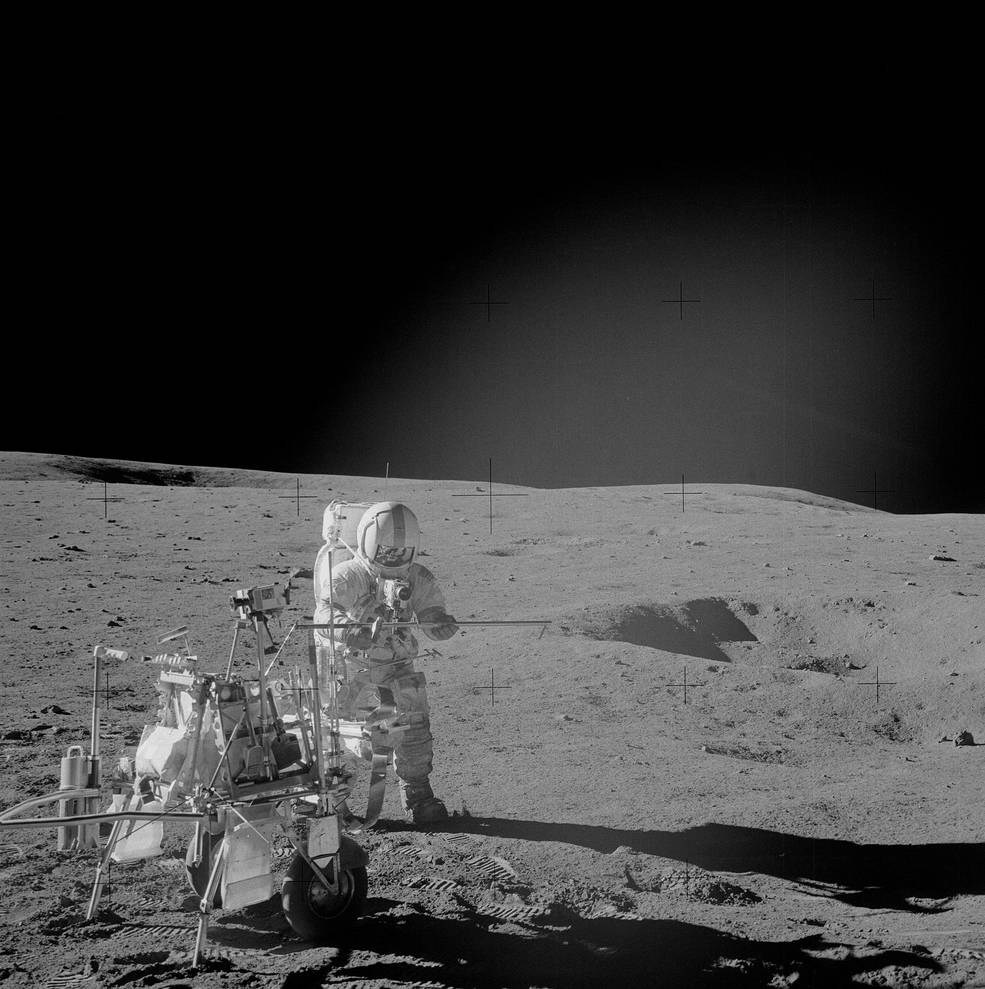

Left: At their first stop during the second moonwalk, Alan B. Shepard and Edgar D. Mitchell have set up the Lunar Portable Magnetometer. Middle: The core drill sample at the first stop during the second moonwalk. Right: Documentary photograph of sample collection at the first stop, with the Modular Equipment Transporter at upper left and the Lunar Module Antares in the far distance.

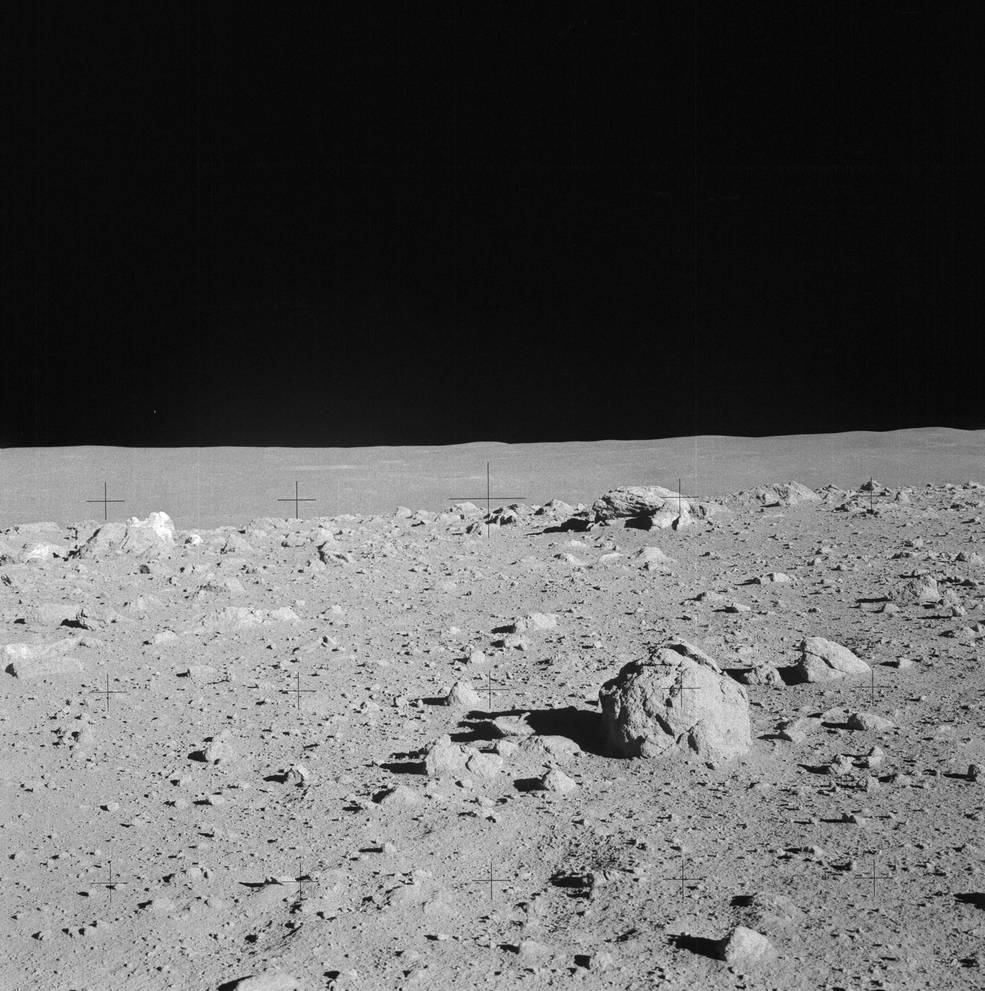

The unexpectedly undulating surface and the large number of craters around which they needed to steer made it difficult for them to gauge their travel time and their precise location through much of the second moonwalk. The overall slope from the LM to the top of Cone Crater was nearly 10 degrees – tough work in the spacesuits, pulling the MET, and trudging in the lunar soil. Unknowingly, they approached to within 150 feet from the edge of the rim, but time and consumables required them to start heading back to the LM. They collected samples that likely represented ejecta from deep within the crust, thrown out during Cone Crater’s formation. Mitchell chipped a sample from Saddle Rock, a large boulder sitting on the southeast rim of Cone Crater. They also collected the largest rock of the mission, nicknamed “Big Bertha”, weighing in at 19.8 pounds. By dating these rocks, scientists determined that Cone Crater formed about 26 million years ago, relatively fresh in lunar geologic terms.

Left: Edgar D. Mitchell consults a map at one of the stops during the second moonwalk. Middle: Alan B. Shepard, pulling the Module Equipment Transporter (MET), climbs a ridge during the second moonwalk. Right: Shepard stands near the MET holding a core tube.

Left: Alan B. Shepard and Edgar D. Mitchell unknowingly stood just 150 feet from the rim of Cone Crater, just to the right of center behind the boulder field. Middle: Near the rim of Cone Crater, Mitchell photographs Saddle Rock shortly after sampling it, with the hammer and sample container sitting on the rock. Right: View from near Saddle Rock on the rim of Cone Crater looking back toward the Lunar Module Antares seen as a small black object in the valley at upper left.

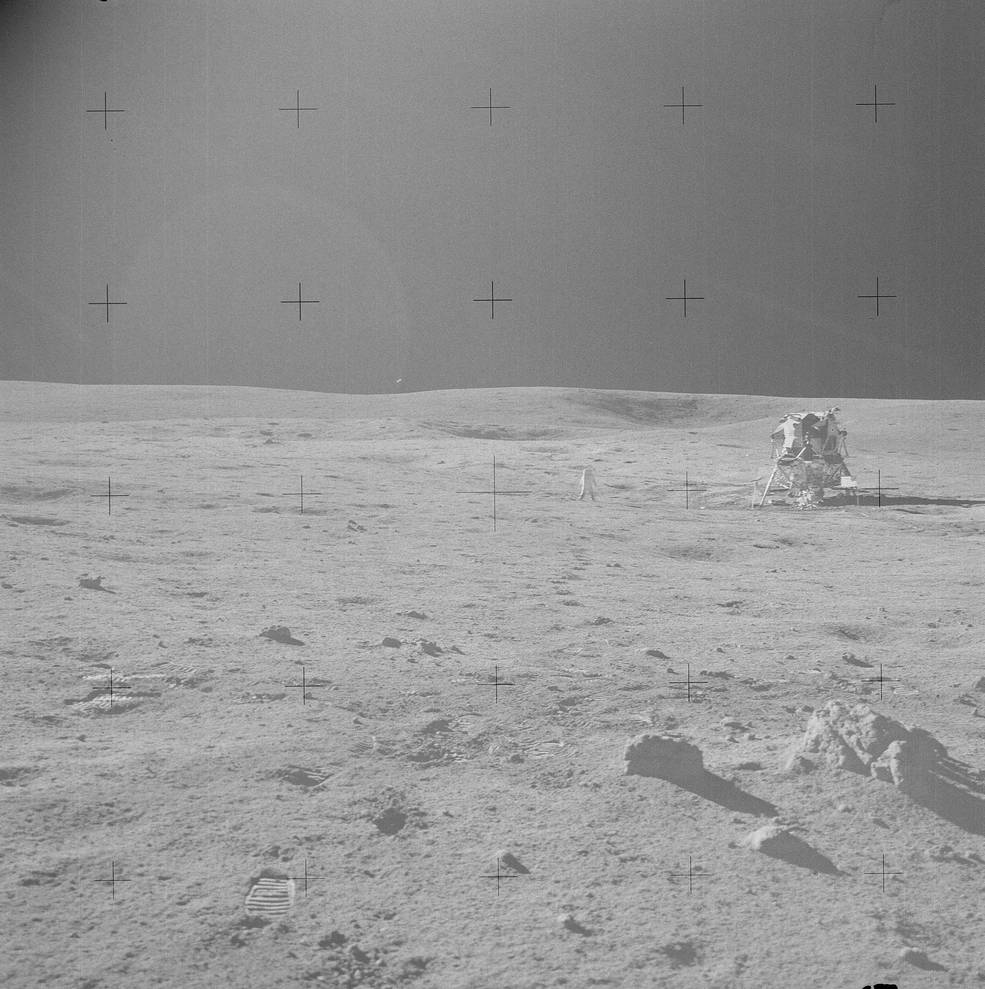

Left: Photograph documenting a sample collection during the return to the Lunar Module Antares, seen in the background. Middle: Turtle Rock, a rock formation north of Antares. Right: Edgar D. Mitchell photographed Antares from Turtle Rock.

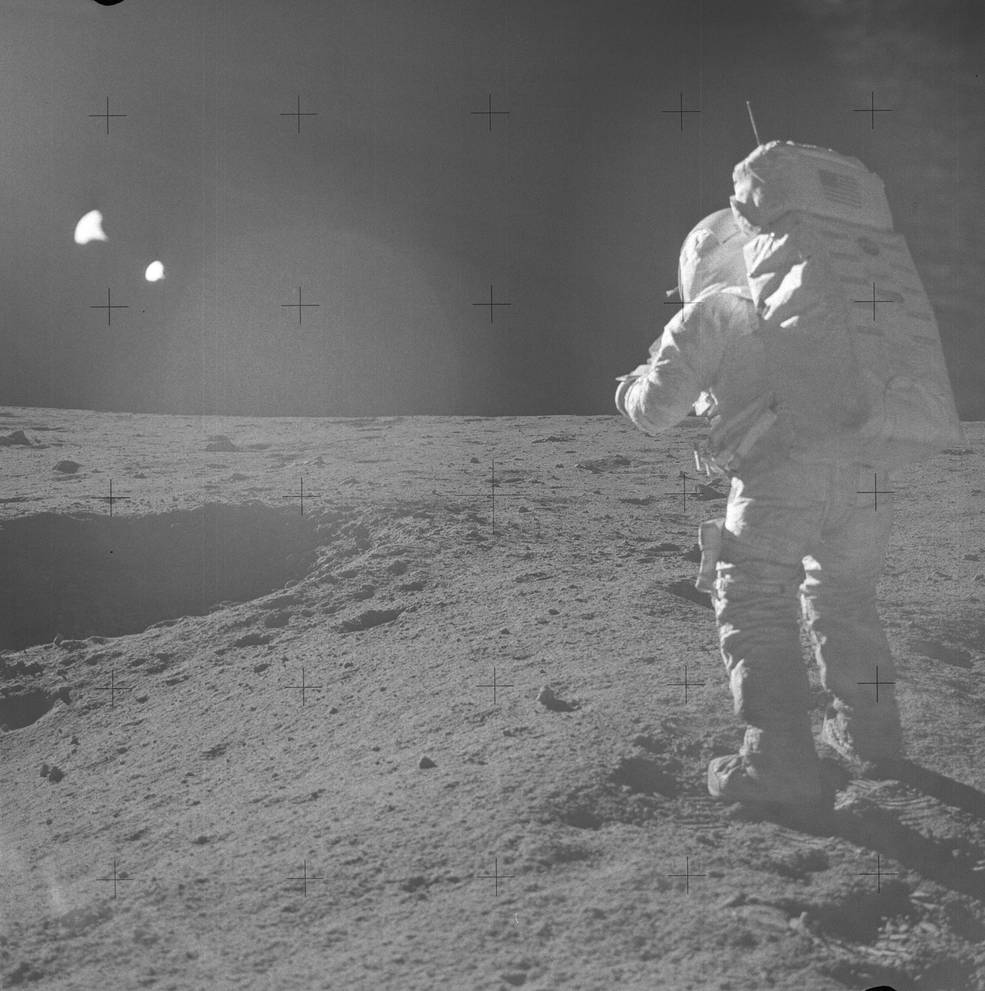

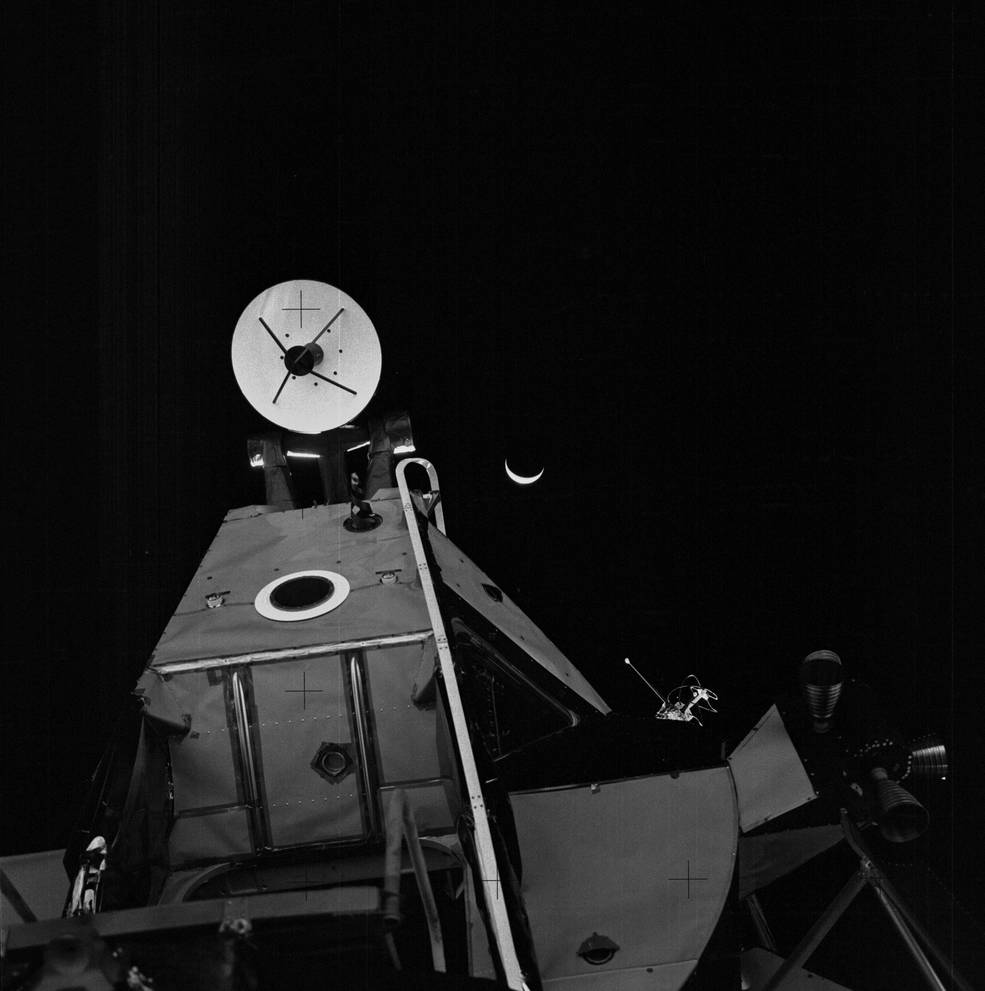

They headed back down toward the LM, taking grab samples of lunar material along the way. When they arrived back at Antares, the two split up, with Shepard returning to the ALSEP to adjust the antenna to resolve a poor communication issue, and Mitchell jogging north to sample some boulders, including one they nicknamed Turtle Rock, they had previously observed and deemed of scientific interest. Back at Antares, Shepard took several photographs of the crescent Earth above the LM, unknowingly also capturing the planet Venus in the frames. Mitchell rolled up the foil collector of the SWC experiment after 21 hours of exposure to the solar wind.

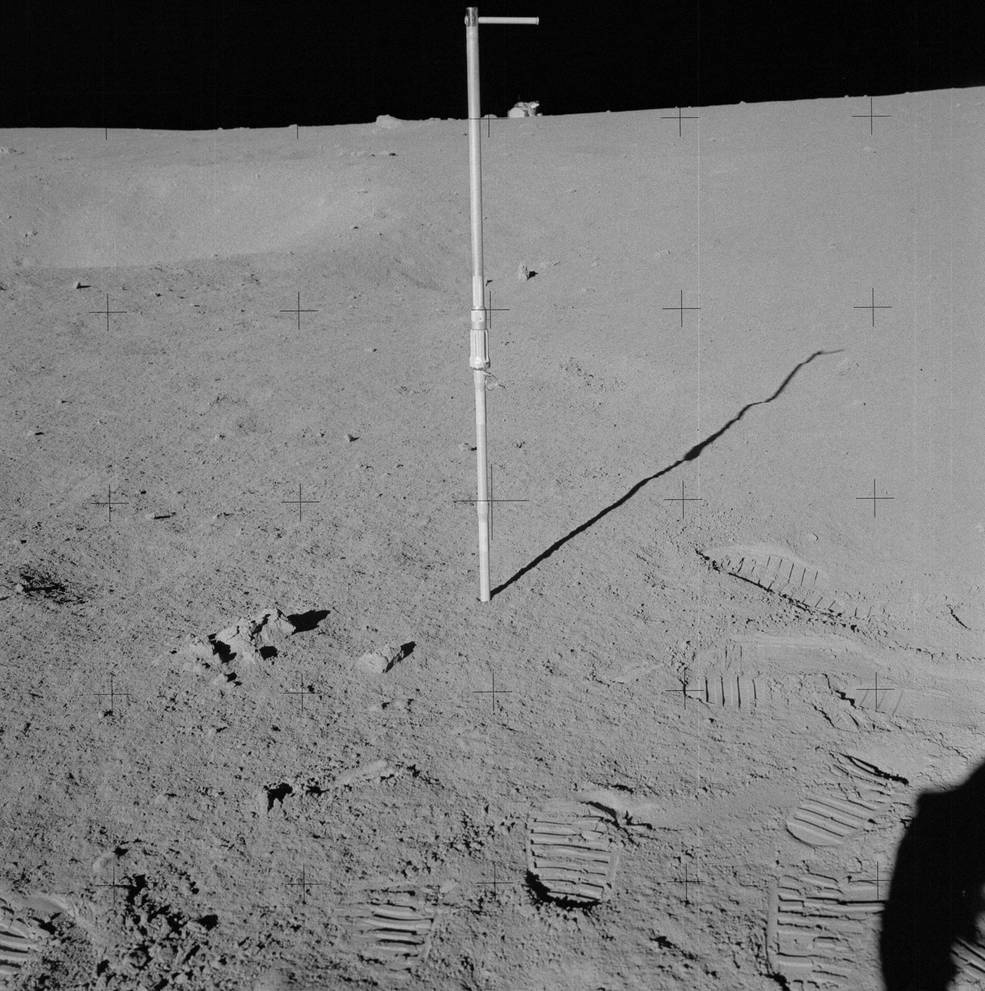

Two images from the television downlink near the end of the second moonwalk. Left: Alan B. Shepard has just swung at a golf ball. Right: Edgar D. Mitchell used the staff for the Solar Wind Collector experiment as a javelin.

An avid golfer, Shepard had snuck a six iron onto the flight and now attached it to the handle of the contingency sample collection tool. Facing the television camera, he dropped a golf ball and said, “a little white pellet that’s familiar to millions of Americans.” Using a one-handed swing to the spacesuit’s rigidity, topped the ball on his first attempt. On his second swing, Shepard connected but only sent the ball about two or three feet to the side, prompting Haise to comment, “that looked like a slice to me, Al.” On his third try, he hit the ball and it travelled about 24 yards, landing in a nearby crater. Shepard dropped and swung at a second ball, claiming that it went for “miles and miles and miles.” In actuality, it travelled about 40 yards in the direction of the ASLEP site. Not to be outdone athletically, Mitchell took the staff that was holding the SWC and threw it javelin-style. It landed in the same crater as Shepard’s first golf ball.

Left: At the end of the second moonwalk, Alan B. Shepard took this photograph of a crescent Earth above the Lunar Module Antares; unknowingly, he also photographed the planet Venus, seen as a very tiny and faint white dot just to the right of the antenna. Middle: Image taken after the second moonwalk from Antares’ right hand window, showing the tracks made by the astronauts’ footsteps and the Modular Equipment Transporter, as well as the “javelin” and one of the golf balls in the crater to the left of center and Turtle Rock in the distance. Right: Photograph taken after the

astronauts jettisoned unneeded equipment, including the two spacesuit backpacks; Shepard’s second golf ball is visible as a small white dot in the direction of the ALSEP site at the upper left of the image.

Shepard and Mitchell completed all their packing activities, stowing all the samples they collected, cameras and film magazines. With a rock box in one hand, Mitchell bounded up the ladder and into the spacecraft. Shepard spoke these last words on the surface, “Okay, Houston, crew of Antares is leaving Fra Mauro Base.” Haise replied, “Al, you and Ed did a great job. Don’t think I could have done any better myself.” After this exchange, Shepard climbed up the ladder and into the LM, and he and Mitchell closed the hatch behind them. The second moonwalk lasted 4 hours and 35 minutes, for a total for both excursions a record-setting 9 hours and 22 minutes. They covered a total distance of more than 13,000 feet, travelling as far as 4,770 feet from the LM, and collected 93 pounds, another record, of lunar samples to return to waiting scientists. The third lunar surface exploration entered the history books. After a 33-hour stay on the surface, Shepard and Mitchell prepared their spacecraft for liftoff to rejoin Roosa waiting aboard Kitty Hawk.

To be continued…

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center