October 1969 proved to be a busy month for Apollo Moon landing crews, past and future, and saw a new manager take the helm of the Apollo Spacecraft Program. The Apollo 11 astronauts and their wives continued their goodwill world tour, begun in late September and ending in early November. The crew of Apollo 12 had one month to go before embarking on its mission to attempt the second lunar landing, with the objective of making a pinpoint touchdown and a secondary objective to examine a robotic lander resting on the surface for two and a half years. The following Moon landing mission, Apollo 13, was then five months away and that crew already busied itself with training for the flight. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union conducted an unprecedented triple human space flight, placing a record seven cosmonauts in space at one time.

On Sept. 25, 1969, NASA appointed veteran astronaut James A. McDivitt as the Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston. McDivitt, selected as an astronaut in 1962, commanded two spaceflights, Gemini 4 in June 1965 that included the first American spacewalk and Apollo 9 in March 1969, the first test of the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit. He succeeded George M. Low who, in that position since April 1967, led the agency’s efforts to recover from the Apollo 1 fire and originated the idea to send Apollo 8 on a lunar orbital mission. Under his tenure, NASA successfully completed five crewed Apollo missions including the first human Moon landing to meet President John F. Kennedy’s goal. MSC Director Robert L. Gilruth assigned Low to plan future programs.

Left: James McDivitt. Right: George Low.

Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, accompanied by their wives Janet, Patricia, and Joan, respectively, continued their Presidential Giantstep goodwill world tour. Kicking off the tour in Mexico City on Sept. 29, by mid-October they had visited three other countries in Latin America, took a two-day rest break in the Canary Islands, and continued on to see 10 European nations. Then they were off to the African and Asian part of the tour. At each stop, heads of state and other dignitaries greeted the astronauts and cheering crowds welcomed them as they rode through the streets in motorcades. A Presidential jet ferried them and their NASA and State Department entourage from city to city.

Left: Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Collins, Aldrin, and Armstrong wearing sombreros during the parade in Mexico City. Right: Apollo 11 astronauts accompanied by their wives during an audience with Pope Paul VI in Vatican City – (left to right) the Collinses, the Pope, the Armstrongs, and the Aldrins.

The Apollo 12 prime crew of Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Richard F. Gordon, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Alan L. Bean and their backups David R. Scott, Alfred M. Worden, and James B. Irwin were heavily engaged in training for all aspects of their mission, scheduled for launch on Nov. 14. In addition to the primary objectives of achieving a pinpoint landing in Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms), deploying several scientific experiments as part of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), and collecting lunar samples, a secondary objective involved inspecting the robotic Surveyor 3 spacecraft that had touched down at that site in April 1967. The astronauts planned to retrieve the spacecraft’s camera and other equipment for return to Earth for scientists to analyze the effects of more than two years in the harsh lunar environment. Compared to Apollo 11’s 21-hour stay on the lunar surface and a single surface Extravehicular Activity (EVA) or spacewalk, Apollo 12 planned to conduct two EVAs during a 32-hour stay.

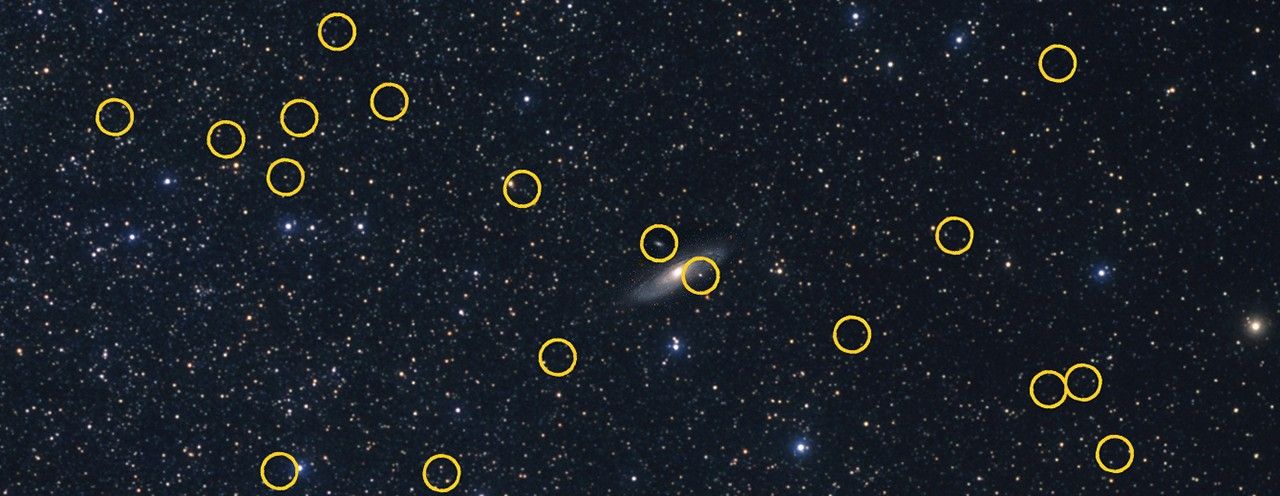

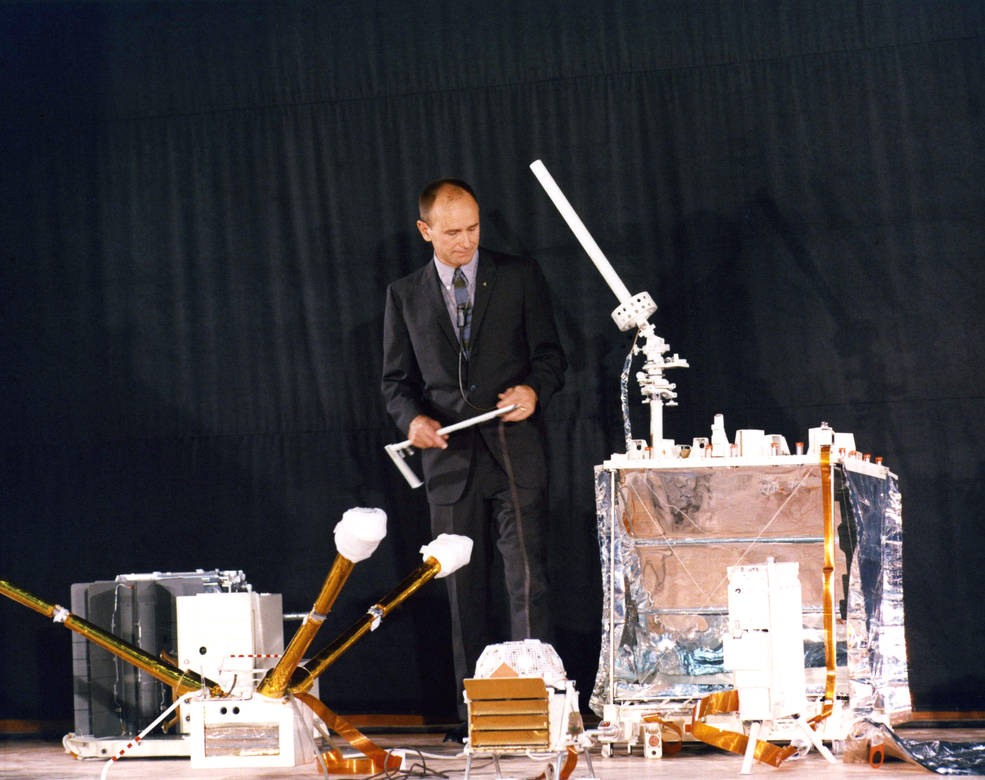

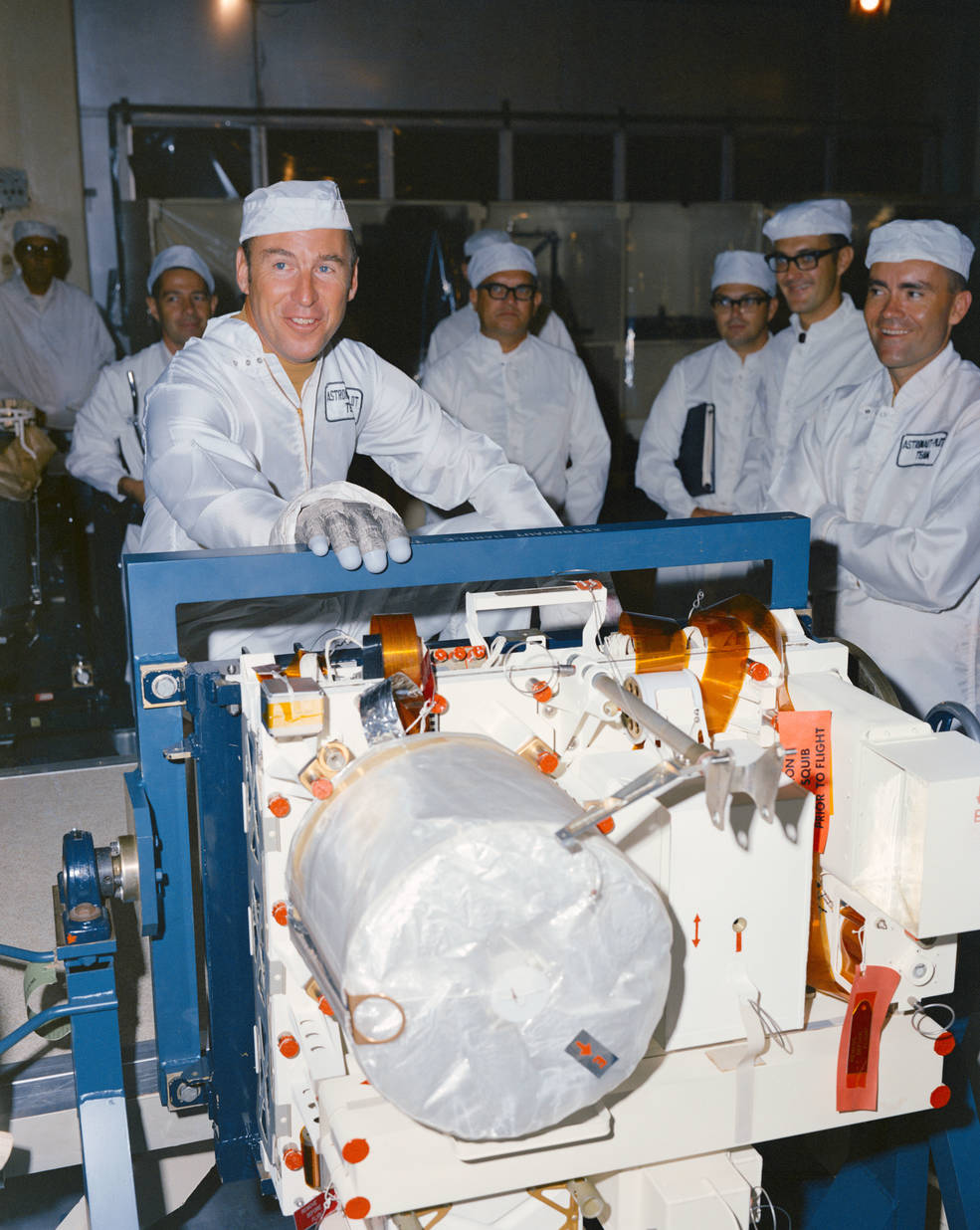

Left: Apollo 12 astronauts Conrad (left) and Bean practice EVA procedures with a mockup of Surveyor 3. Right: Apollo 12 astronaut Bean demonstrates some of the ALSEP hardware, (left to right) the RTG, the magnetometer, the solar wind spectrometer, and the central station during a press conference at KSC.

The Apollo 12 ALSEP, the first deployed on the Moon, consisted of six experiments, with one additional experiment separate from the overall package. A central station provided communications between the various experiments and ground controllers and a Radioisotope Thermo-electric Generator (RTG) provided 70 watts of power through the heat generated by the radioactive decay of a plutonium-238 fuel element. The ALSEP experiments were:

- The Lunar Surface Magnetometer (LSM) measured the variations of the lunar magnetic field.

- The Passive Seismic Experiment Package (PSEP) recorded meteorite impacts and moonquakes, and was sensitive enough to record astronauts’ footsteps.

- The Solar Wind Spectrometer (SWS) measured the energy, density, direction, and variations of travel of the particles emitted by the Sun.

- The Lunar Dust Detector (LDD) measured the amount of dust accumulating on the lunar surface.

- The Suprathermal Ion Detector Experiment (SIDE) and the Cold Cathode Ion Gauge Experiment (CCGE) measured the number and types of ions on the Moon.

The Solar Wind Composition (SWC) experiment, which the Apollo 11 astronauts also deployed, collected samples of the solar wind on a thin sheet of aluminum foil and returned to Earth with the astronauts for postflight analysis. During a press conference at KSC on Oct. 2, Bean, who had prime responsibility for deploying the scientific experiments, provided the assembled reporters with a demonstration of the ALSEP hardware components.

Left: Apollo 12 backup astronauts Irwin (left) and Scott during briefings prior to geology training near Flagstaff. Right: Apollo 12 astronauts Conrad (left) and Bean during geology field training near Flagstaff.

The Apollo 12 prime and backup Moon walkers (Conrad, Bean, Scott, and Irwin) completed their last geology field trip on Oct. 9 and 10 at an artificially created crater field near Flagstaff, Arizona. Accompanying them on the exercise were astronauts Edward G. Gibson, who served as Capsule Communicator (Capcom) as he would during the flight, and Don L. Lind, and geologists Uel S. Clanton of NASA and Edward W. Wolfe of the United States Geological Survey. To add realism to the training, the astronauts not only studied geology but also simulated the traverses they would undertake on the lunar surface, including carrying training models of the equipment, and communicating via radio to the simulated Capcom. Geologists staffed the Science Support Room in Mission Control at MSC as they would during the actual mission.

Left: Apollo 12 astronauts (left to right) Bean, Gordon, and Conrad during a press conference at MSC. Right: Apollo 12 astronauts Conrad (on the “surface”) and Bean (on the ladder) practice EVA procedures around the LM.

During a press conference at MSC on Oct. 11, Conrad, Gordon, and Bean provided an overview of their mission to assembled reporters. They announced the call signs they would use during the flight to differentiate between the two spacecraft – their Command and Service Module they named Yankee Clipper and their LM Intrepid. They selected the names from entries submitted by employees of North American Rockwell Space Division and of Grumman Aerospace Corporation, prime contractors for the CSM and LM, respectively. Throughout October, the three astronauts conducted numerous training runs in the spacecraft simulators and several sessions practicing for the lunar surface EVAs.

Left: Apollo 12 Commander Conrad about to take off on a training flight in the LLTV. Right: Apollo 12 Backup LMP Irwin (at center, wearing a helmet) at the LLRF.

Apollo astronauts had two important training tools to prepare them for the actual Moon landings – the Lunar Landing Research Facility (LLRF) at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, and the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV) at Ellington Air Force Base near MSC. The LLRF consisted of a 400- by 230-foot A-frame structure with a gantry used to manipulate a full-scale Lunar Excursion Module Simulator (LEMS). Workers modelled the base of the LLRF with fill material to resemble the Moon’s surface. The LLRF simulated piloting the LM in the final 150 feet of the descent to the lunar surface and was available to train both Commanders and LMPs and their backups. Irwin completed flights in the LLRF on Oct. 18. The LLTV, often dubbed “the flying bedstead,” was a high-fidelity simulator of the LM’s flying characteristics especially of the final 500 feet of the descent. Challenging to fly, Apollo Commanders considered the LLTV an essential tool to teach them the skills to pilot the LM to the lunar surface. Throughout October, Conrad and Scott completed several simulated landings with the LLTV.

In October 1969, Apollo 13 was scheduled for a March 12, 1970, launch to visit the Fra Mauro highlands region of the Moon. With the mission’s increased emphasis on science, geology training for the Apollo 13 prime crew of Commander James A. Lovell, CMP Thomas K. Mattingly, and LMP Fred W. Haise, and their backups John W. Young, John L. Swigert, and Charles M. Duke, took on greater importance. Like the Apollo 12 astronauts before them, they had the advantage of examining actual lunar samples returned by Apollo 11. To further prepare for their lunar surface excursions, Lovell, Haise, Young, and Duke, accompanied by geologist-astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt and Caltech geologist Leon T. “Lee” Silver, spent a week into early October in Southern California’s Orocopia Mountains immersed in a geology boot camp. A second field trip to Arizona’s Meteor Crater on Oct. 24, and several more to other sites into early 1970, further honed their skills as geologists. Prime and backup CMPs Mattingly and Swigert received training in the conduct of orbital geology, primarily photography, from NASA geologist Farouk al-Baz.

Left: Apollo 13 astronauts Lovell (at left) and Haise (at right) inspect the ALSEP hardware. Right: Apollo 13 astronauts Lovell (second from left) and Haise (second from right) during inspection of ALSEP hardware.

Apollo 13 also planned to deploy an ALSEP complement of experiments, a slightly different set than that planned for Apollo 12. Lovell, Haise, Young, and Duke conducted several training sessions to become familiar with the science equipment, including a formal crew fit and function test on Oct. 10 at KSC. Young completed several flights in the LLRF at Langley on Oct. 8 and 9 to train for a Moon landing.

Left: The seven cosmonauts (holding flowers) and senior Soviet space managers assembled in front of the rocket for the Soyuz 6 mission the day before launch. Right: The seven cosmonauts (left to right) Gorbatko,Yeliseyev, Filipchenko, Volkov, Shatalov, Shonin, and Kubasov pose for a group photo.

Credits: RKK Energiya.

During this time, the Soviet Union conducted an interesting set of human space flights. Sometimes referred to as the Troika flight, after the Russian sleighs drawn by three horses, Soyuz 6, 7, and 8 marked the first time three crewed spacecraft orbited the Earth at the same time, with a record-setting seven cosmonauts in space simultaneously*. First to launch from the Baykonur Cosmodrome on Oct. 11 was Soyuz 6 with Georgi S. Shonin and Valeri N. Kubasov aboard, on a flight that had originally been planned as a solo mission in May 1969, but Soviet managers decided to attempt the more challenging triple flight. A unique objective of Soyuz 6 involved Kubasov performing vacuum welding experiments using the Vulkan apparatus mounted inside the spacecraft’s orbital compartment. The next day, Soyuz 7 took off with three cosmonauts aboard, Anatoli V. Filipchenko, Vladislav N. Volkov, and Viktor V. Gorbatko. Finally, on Oct. 13, Soyuz 8 launched with Vladimir A. Shatalov and Aleksey S. Yeliseyev, from the same launch pad that Soyuz 6 used two days earlier. Shatalov and Yeliseyev became the first humans to make two spaceflights in one calendar year, both having flown as part of the Soyuz 4 and 5 docking and crew exchange mission in January 1969†. Based on that, observers believed that a docking and crew exchange would take place between Soyuz 7 and 8, with the Soyuz 6 crew observing from a short distance. Indeed, the cosmonauts attempted several docking attempts, but for a variety of reasons none succeeded. Beginning on Oct. 16 and at 1-day intervals, each Soyuz returned to Earth, landing on the snow covered steppes of Soviet Kazakhstan.

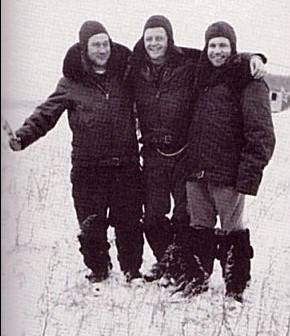

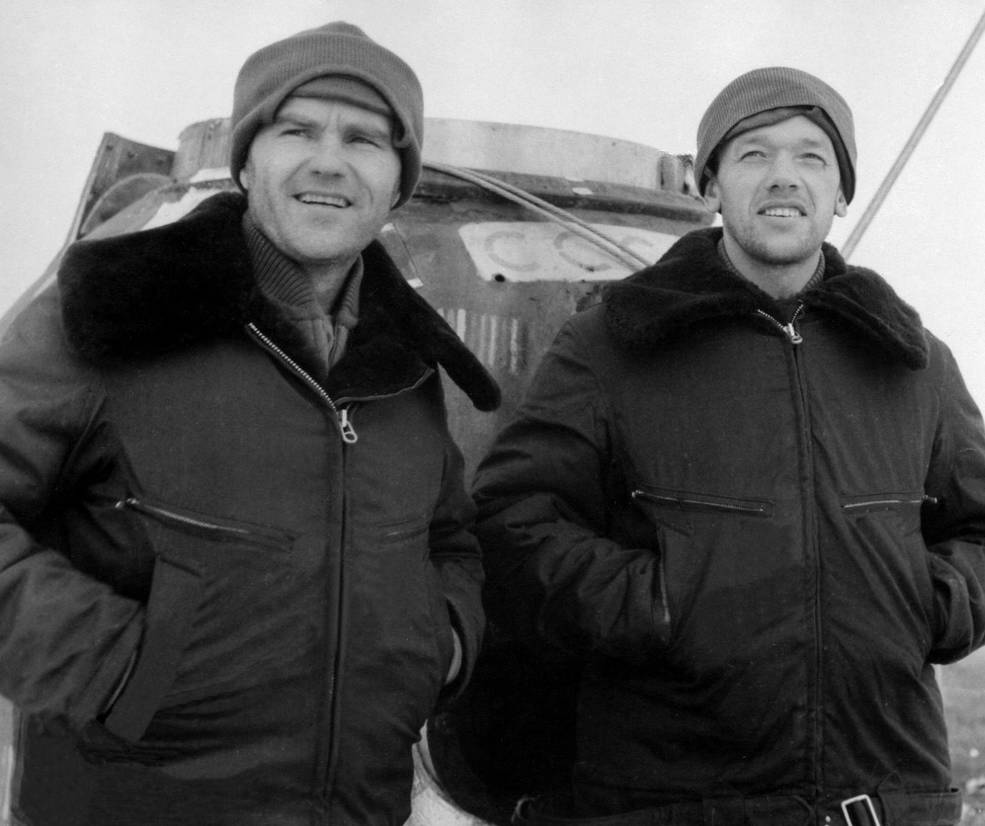

Left: Soyuz 6 cosmonauts Shonin (left) and Kubasov shortly after landing. Middle: Soyuz 7 cosmonauts (left to right) Filipchenko, Volkov, and Gorbatko shortly after landing. Right: Soyuz 8 cosmonauts Shatalov (left) and Yeliseyev standing in front of their capsule shortly after landing.

Credits: RKK Energiya.

*That record stood until February 1984, when eight people orbited at one time – three aboard the Salyut-7 space station and five aboard STS-41B.

†American astronaut Thomas P. Stafford then held the record for the shortest time between two spaceflights – 169 days between the splashdown of Gemini 6 in December 1965 and the launch of Gemini 9 in June 1966.