With the successful completion in March 1969 of the Apollo 9 mission that tested the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit, NASA’s confidence rose that President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth before the end of the decade was achievable. Apollo 10 would carry out a dress rehearsal of the landing in May and it was hoped that Apollo 11 would complete the actual landing in July. However, much work remained before that could be accomplished.

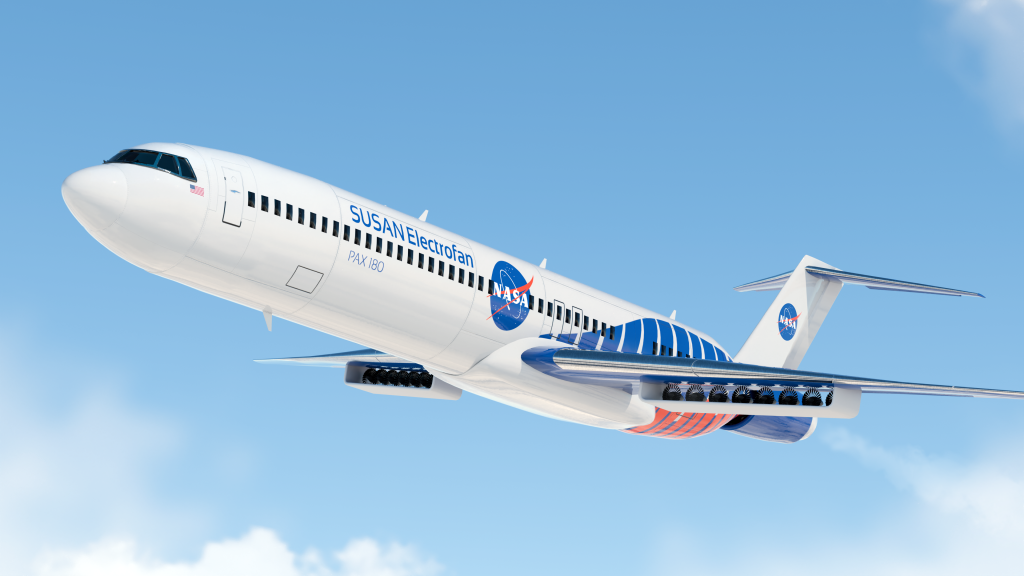

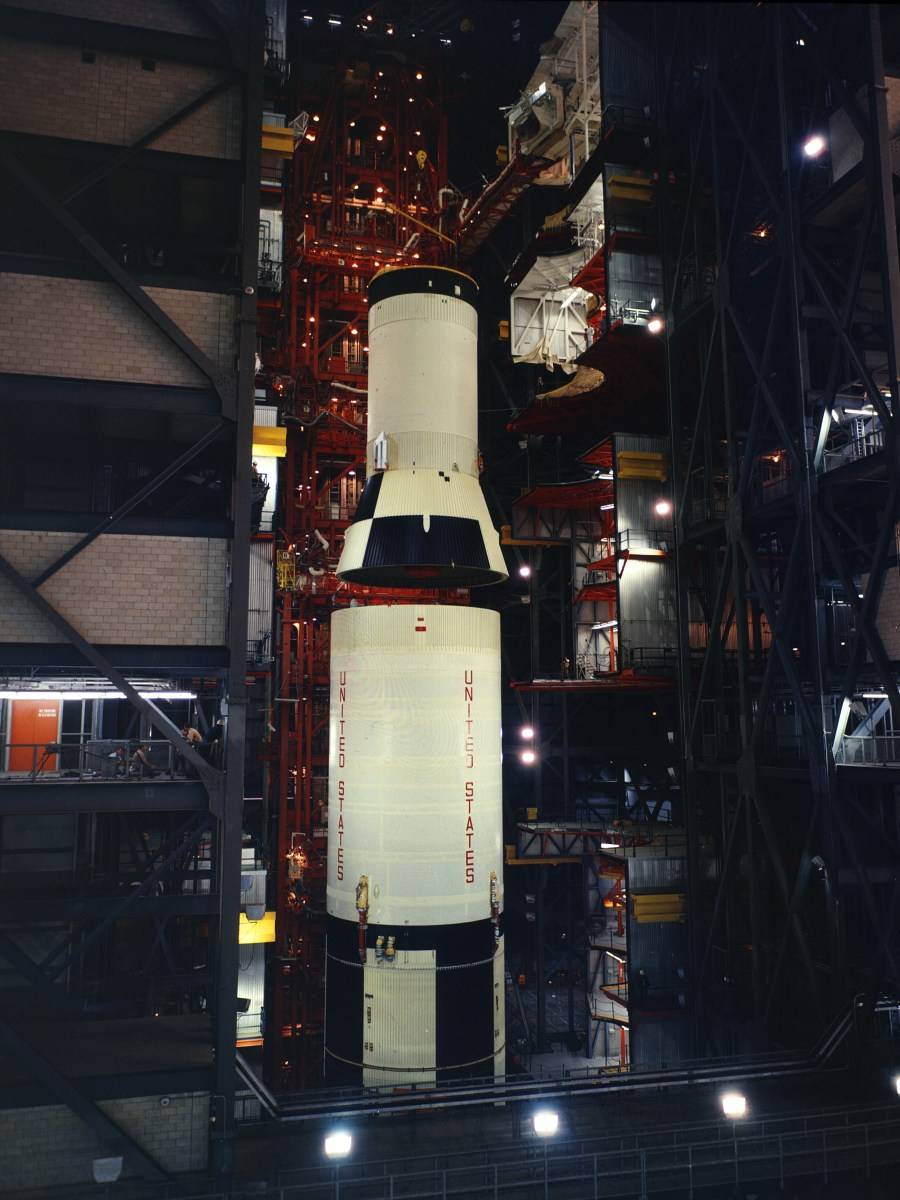

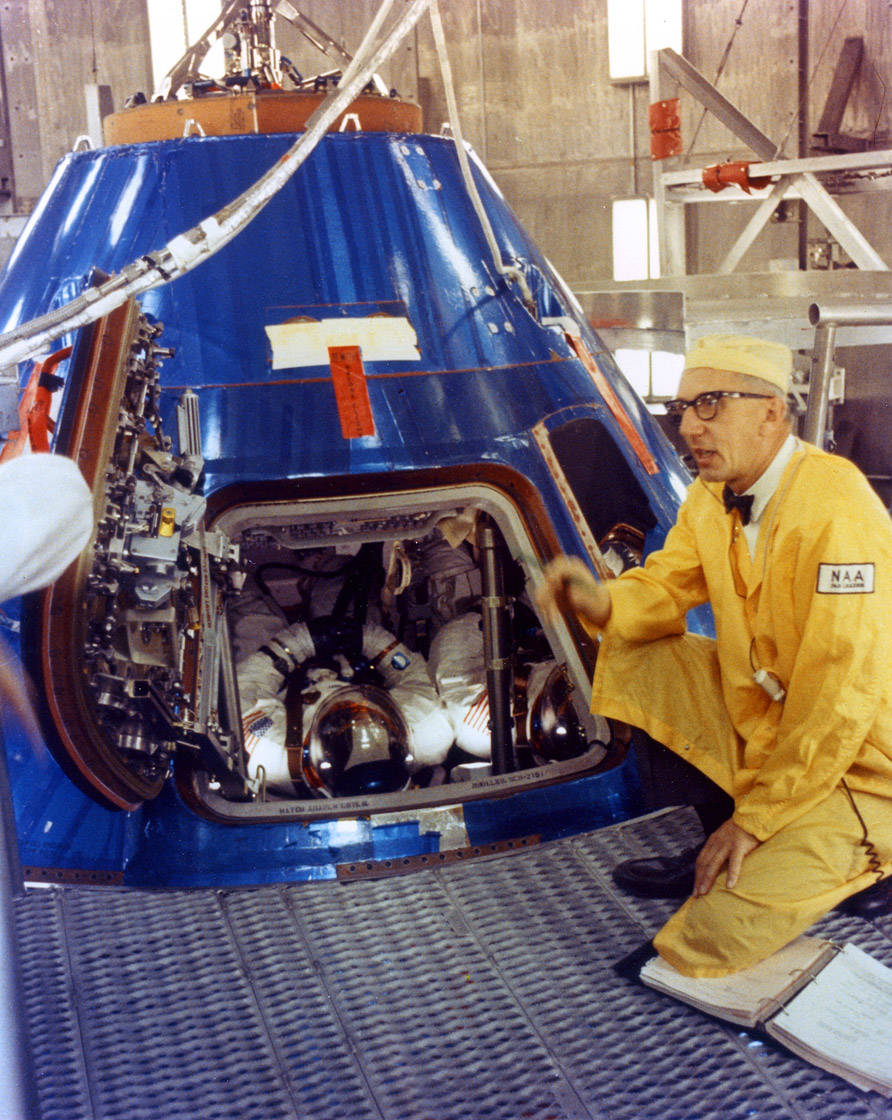

Left: Stacking of the third stage onto the Apollo 11 Saturn V in the VAB. Middle: Apollo 11 crew inside their Command Module

prior to an altitude test. Right: Apollo 11 backup crewmembers Haise (left) and Lovell about to enter the Lunar Module for an altitude test.

Flight hardware for the Apollo 11 mission was undergoing testing at the Kennedy Space Center. In the Vehicle Assembly Building, the three stages of the Saturn V rocket were in checkout following their stacking in February and early March. In the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building, the prime crew of Commander Neil A. Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins tested their Command Module in the altitude chamber, followed by their backups James A. Lovell, Fred W. Haise, and William A. Anders. Armstrong and Aldrin, as well as Lovell and Haise, also conducted altitude tests with their LM.

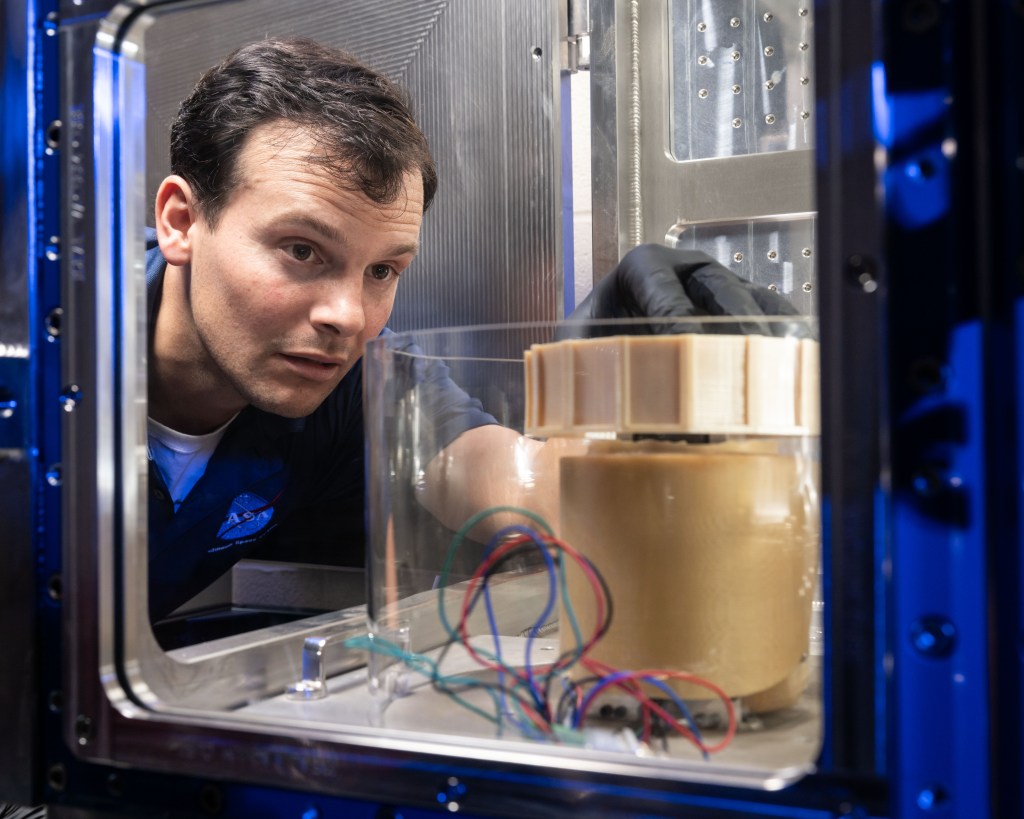

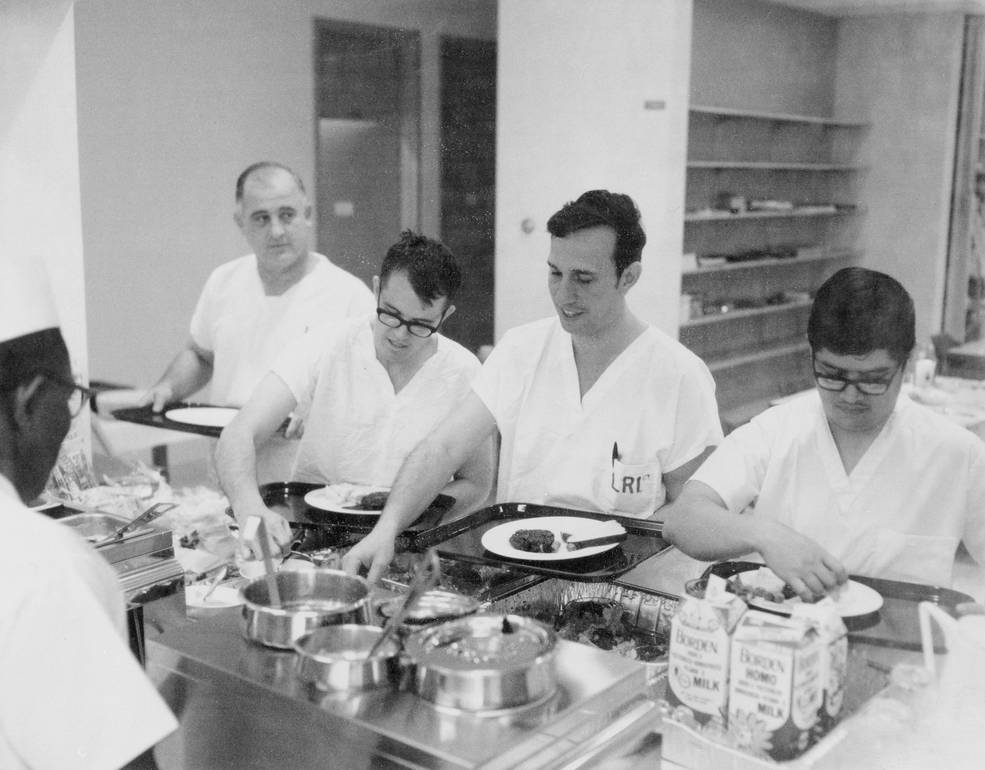

Left: Technician uses a microscope inside a glovebox during the LRL simulation. Middle: Staff in the LRL’s Crew Reception Area

galley during the simulation. Right: Mobile Quarantine Facility being lifted from the USS Guadalcanal prior to transport back to Houston.

A 30-day simulation was under way in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston. The LRL, a critical ground component of the Apollo program, was specially designed and built to isolate the astronauts, their spacecraft, and rock samples returning from the Moon to prevent back-contamination of the Earth by any possible lunar micro-organisms, and to maintain the lunar samples in as pristine a condition as possible. The simulation was the most complex test of the facility to verify that all its components would be ready to support crewmembers and their samples returning from the Moon. A separate seven-day simulation of the astronaut quarantine capabilities in the LRL’s Crew Reception Area began on March 25. Fifteen NASA and contractor employees, most of whom would participate in the activities following the actual lunar landing mission, demonstrated the logistics of maintaining astronauts and support staff in isolation. All biological barriers were operative during the simulation, and the only contact test personnel had with the outside world was via telephone or through glass walls. The first part of the test included the simulated arrival of lunar materials and film, followed the next day by the arrival of the stand-in crew. The last part of the test included the process for releasing the crew and personnel from quarantine. Earlier in the month, a successful simulation of recovery and quarantine operations with the Mobile Quarantine Facility was completed aboard the USS Guadalcanal in conjunction with the recovery of the Apollo 9 crew.

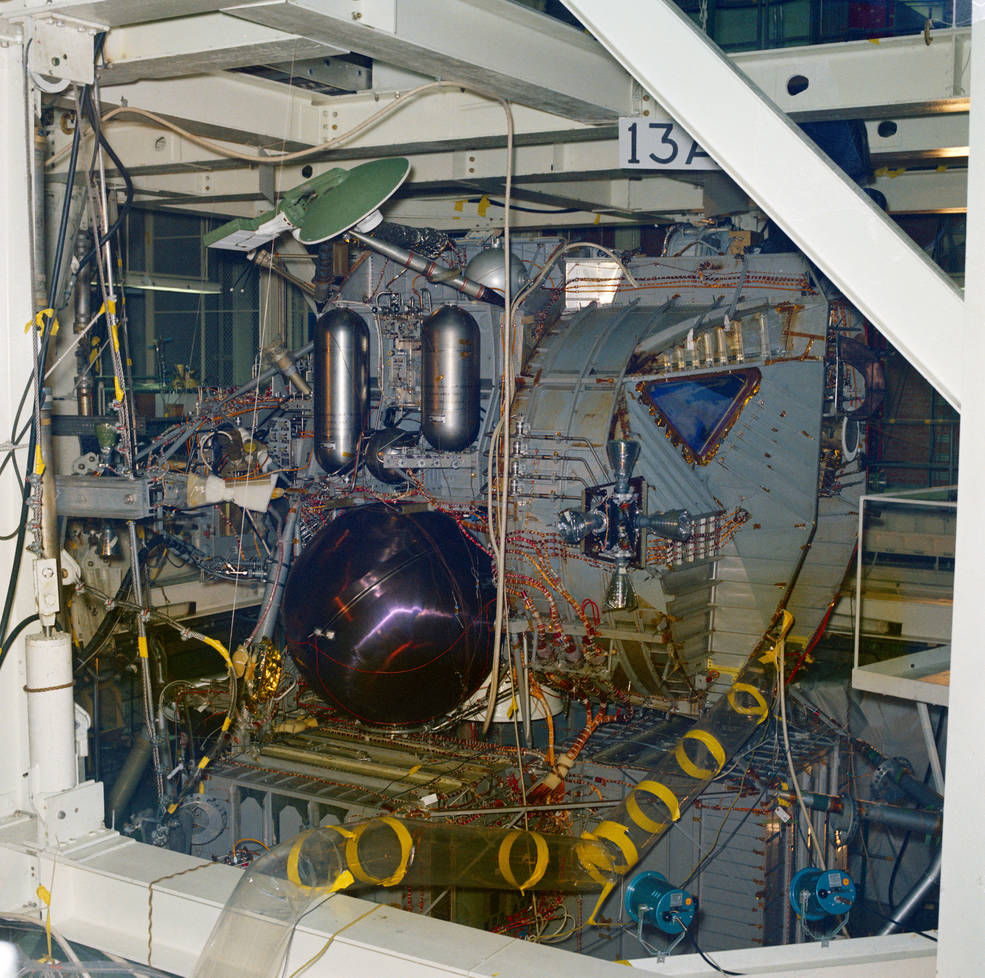

Left: LM-2 in the test stand in the VATF prior to a drop test.

Right: Landing leg on LM-2 in the VATF test stand.

To certify the LM for lunar landings, engineers at MSC conducted drop tests with Lunar Module-2 (LM-2) in the Vibration and Acoustics Test Facility (VATF). The series of five drop tests began March 21 and were completed in early May. NASA originally built LM-2 for a second unpiloted test flight of the spacecraft, but the first test during the Apollo 5 mission in January 1968 was so successful that NASA deemed a second flight unnecessary. By using LM-2, a flight-like vehicle with all subsystems installed, engineers evaluated the durability of those systems. Engineers dropped LM-2, instrumented with accelerometers, from heights of eight to 24 inches onto pedestals of varying heights and slopes to simulate landings on rough lunar terrain. The vehicle passed with flying colors and was certified for the first lunar landing.

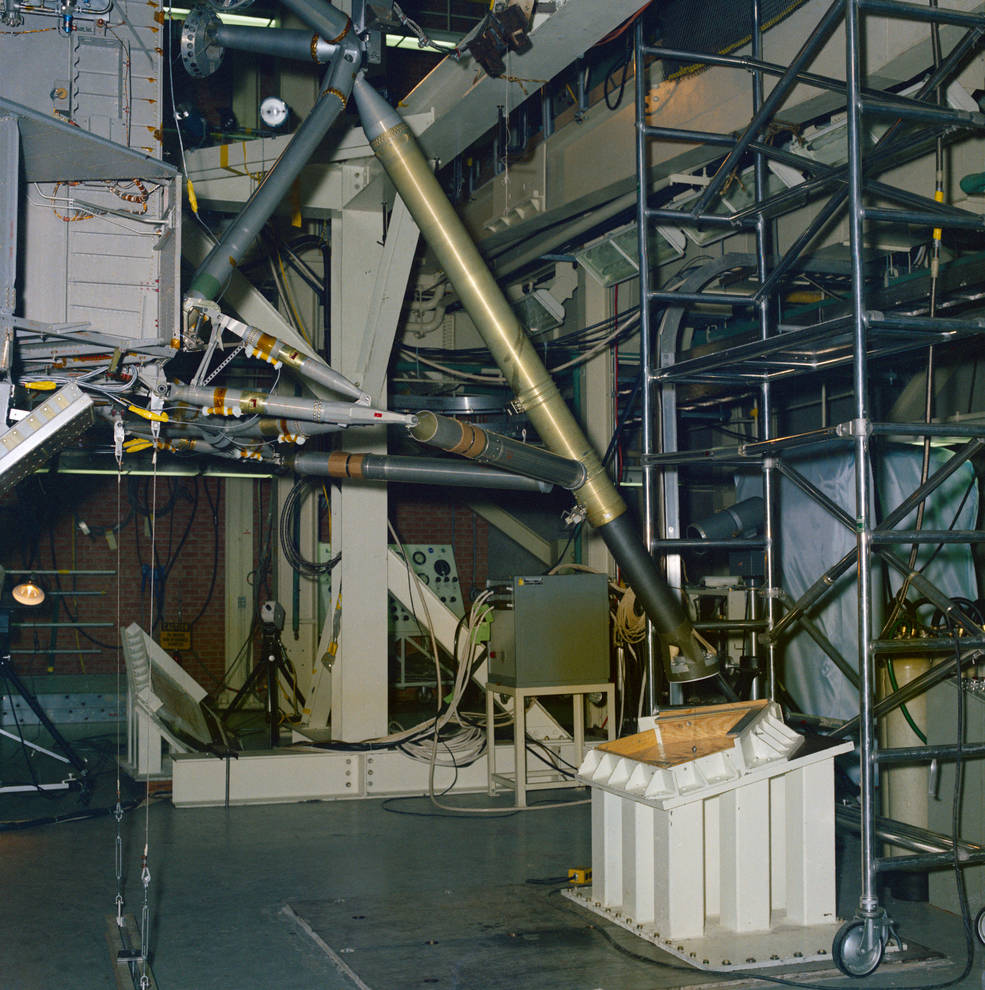

Left: NASA pilot Algranti ejecting from LLTV-1 seconds before it crashed.

Right: First flight of LLTV-2 after resumption of flights, with pilot Ream at the controls.

Managers at MSC conducted a Flight Readiness Review (FRR) on March 10 to determine the flight status of the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV), used by Apollo commanders to simulate the characteristics of the LM during the final 200 feet of a lunar landing. Following the crash of LLTV-1 in December 1968, during which pilot Joseph P. Algranti ejected to safety, the remaining two vehicles were grounded while an investigation was carried out to determine the cause. In May 1968, Armstrong had similarly ejected to safety when his Lunar Landing Research Vehicle, an earlier version of the LLTV, went out of control and crashed. During the FRR, managers decided that flights with LLTV-2 could resume pending resolution of some open issues. The managers reconvened on March 31 to review the open work and agreed that flights of LLTV-2 with test pilots could resume as soon as possible, and Harold “Bud” Ream made the first test flight on April 7. A decision on resuming flights with astronauts was not made until June 13, with Armstrong making the first of his eight flights the next day, just over a month before the actual Moon landing.

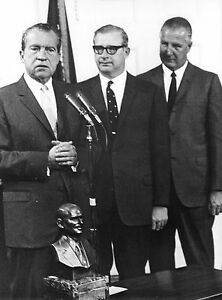

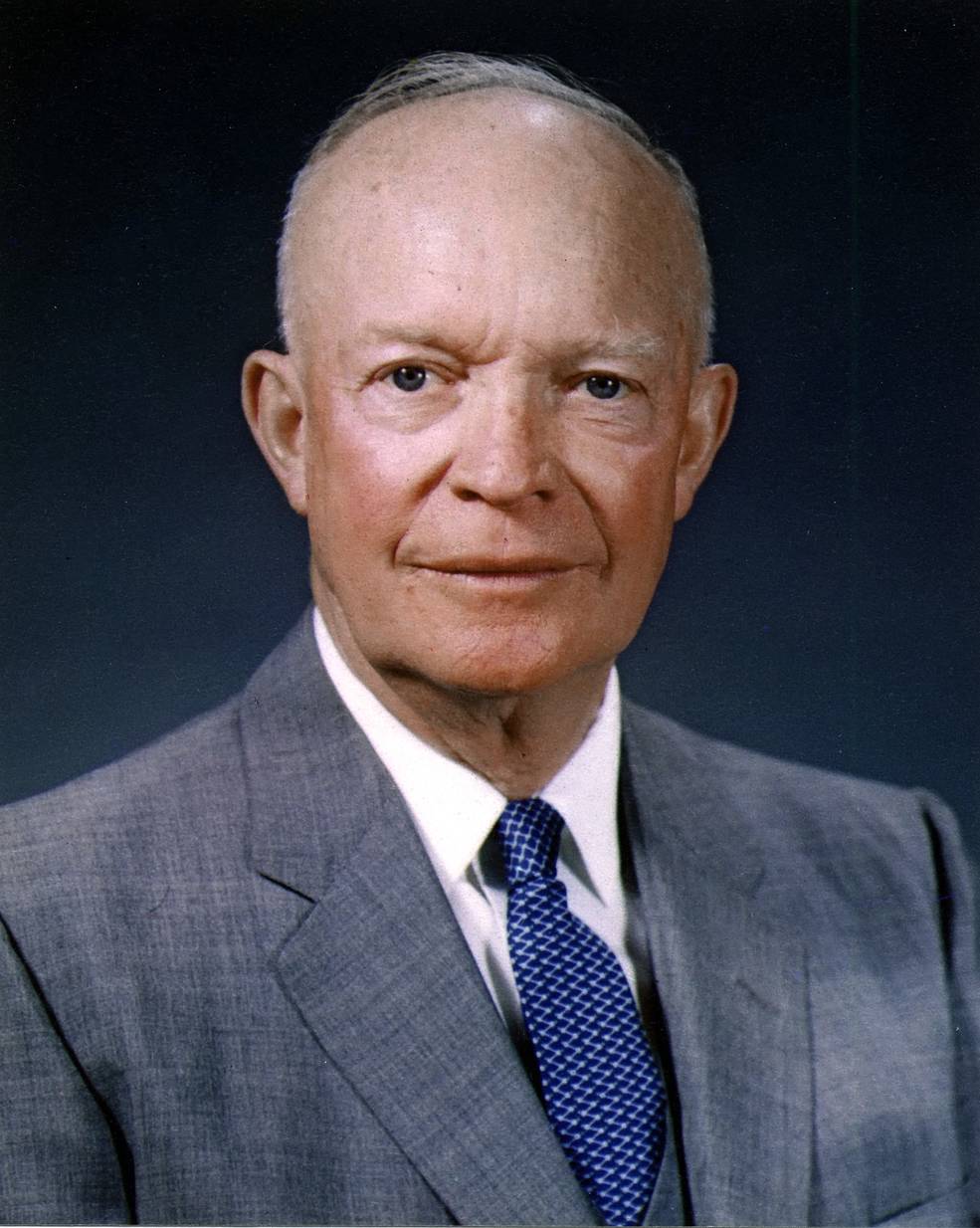

Left: In the White House, President Nixon (left) announced the nomination of

Paine (middle) as NASA’s third Administrator, as Vice President Agnew

looked on. Right: Official portrait of former President Eisenhower taken in 1959.

On March 5, in a White House ceremony President Richard M. Nixon announced that he was nominating Thomas O. Paine, Acting NASA Administrator since October 1968, to be NASA’s third Administrator. The Senate confirmed the nomination on March 20 and Paine assumed the role the next day, being sworn in by Vice President Spiro T. Agnew. On March 28, the nation learned of the death of former President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the age of 78. As President, Eisenhower was instrumental in the establishment of NASA in 1958 and supporting the Agency in its formative years.