Two weeks before the Apollo 10 launch, engineers at Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39B worked to overcome a problem with the Saturn V rocket’s first stage. On April 28, 1969, a planned power outage to conduct maintenance at the Launch Control Center also caused power to be lost at the launch pad, where not all systems had backup power. The rocket’s first stage was loaded with its flight load of RP-1 fuel, and the loss of power caused the failure of pneumatic controls keeping prevalves at the bottom of the tank closed and the prevalves opened, spilling 5,280 liters of RP-1 fuel onto the launch pad’s flame trench. Since the fuel tank didn’t have any relief valves to allow air to enter the tank as fuel drained out, the loss of fluid volume caused the top of the tank to dimple inward. Quick thinking engineers at the pad instituted a work around to refill the tank and the dimple popped out with a very audible “boomp.” Launch pad manager John J. “Tip” Talone concluded of the quick action, “It worked like a champ.” Concern with any possible cracks in the fuel tank was resolved through non-destructive testing and visual inspections.

Left: Apollo 10 astronauts (left to right) Cernan, Stafford, and Young. Right: Apollo 10 Saturn V during the CDDT.

The fuel spill incident occurred during Apollo 10’s Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT), a full dress rehearsal for the actual countdown to launch that consisted of two parts. The wet test included fueling the rocket as if for flight, with the countdown cutting off just prior to first stage engine ignition, and did not involve the flight crew. This was followed by the dry test, an abbreviated countdown without fueling the rocket but with the flight crew boarding the Command Module (CM) as if on launch day. The wet countdown was completed on May 5, and the dry test the next day, with astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, Eugene A. Cernan, and John W. Young suiting up and climbing aboard their CM Charlie Brown. As launch day approached, the trio were spending many hours in the CM and Lunar Module (LM) simulators, rehearsing various aspects of their upcoming mission. Controllers in Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, participated in many of the simulations.

Left: Cernan about to enter the LM simulator, with mascot Snoopy looking on. Right: Young (left) and Stafford about to enter the CM simulator.

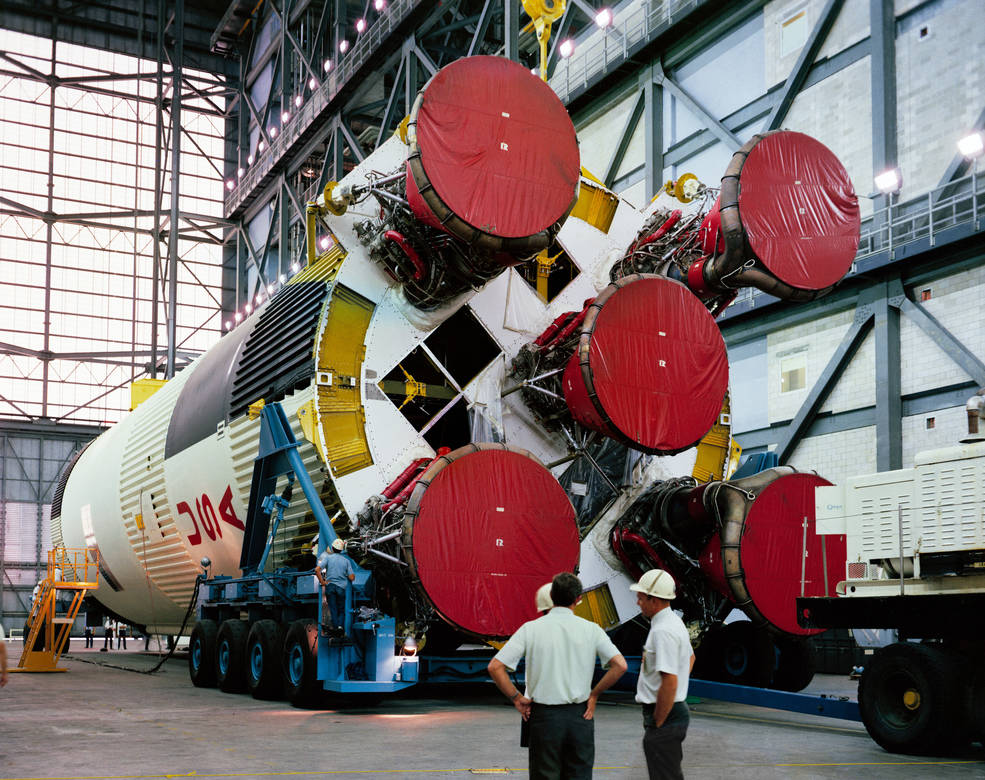

Looking beyond the first Moon landing, NASA’s preparations were well underway for Apollo 12, the second attempt expected to occur about four months after the first. Flight hardware for this mission continued arriving at KSC with the S-IC first stage being delivered on May 3. Four days later, workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) erected that stage on its Mobile Launch Platform. Stacking of the second and third stages took place later in the month. The Apollo 12 crew of Charles “Pete” Conrad, Alan L. Bean, and Richard F. Gordon had begun their training including a two-day geology field trip to Big Bend, Texas, in early May.

Left: First stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V in the VAB. Right: Shepard in Mission Control after the Apollo 10 splashdown.

On May 5, 1969, Alan B. Shepard marked the eighth anniversary of his suborbital Mercury-Redstone-3 mission, during which he became the first American in space. Two days later, Shepard had more reason to celebrate – flight surgeons returned him to full space flight status. Shepard was grounded in 1963 when he developed Meniere’s disease, an inner ear condition that causes dizziness. A minor operation in 1968 corrected the problem and Shepard remained symptom-free. Said Shepard of his return to flight status, “The sooner I get off the ground, the better.” He went on to command Apollo 14 in 1971, becoming the only Mercury 7 astronaut to walk on the Moon.

Read Talone’s oral history with the JSC History Office.