In May 1972, during a summit meeting in Moscow between the United States and the Soviet Union, President Richard M. Nixon and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Aleksey N. Kosygin signed an Agreement on Cooperation in the Exploration and the Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes. One outcome of the agreement, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, called for the docking in July 1975 of an American Apollo and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in low Earth orbit and the exchanges of crewmembers during two days of joint operations. To manage the programmatic and technical aspects of the project, each nation named an experienced leader. The Soviets designated USSR Academy of Science member and senior manager at RKK Energiya Konstantin D. Bushuyev as the Project Director for their side while NASA named veteran flight director Glynn S. Lunney as the American ASTP project director.

Left: President Nixon (left) and Chairman Kosygin sign the Space Cooperation Agreement. Right: ASTP Project Directors Bushuyev (left) and Lunney during a meeting in Houston in 1973. Credits: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

Each nation selected a cadre of cosmonauts and astronauts to participate in the joint project. Because the Soviets planned to ready two Soyuz spacecraft in parallel for added redundancy, they named two prime crews. To the first prime crew they named veteran cosmonauts Aleksey A. Leonov and Valeri N. Kubasov, and veterans Anatoli V. Filipchenko and Nikolai N. Rukavishnikov to the second prime crew. They named Vladimir A. Dzhanibekov and Boris D. Andreyev as the first backup crew and Yuri V. Romanenko and Aleksandr S. Ivanchenko as the second, all four space rookies selected as cosmonauts in 1970. This marked the first time the Soviets publicly named any cosmonauts before they flew in space. The Americans designated the prime Apollo crew as Thomas P. Stafford, Vance D. Brand, and Donald K. Slayton, backed up by Alan L. Bean, Ronald E. Evans, and Jack R. Lousma. At the time NASA named the crews, only Stafford and Evans had any spaceflight experience. Although Slayton had been one of the original seven Mercury astronauts, he had been grounded due to a medical issue and was reinstated prior to being assigned to the mission. NASA also named four astronauts as support crewmembers – Karol J. Bobko, Robert L. Crippen, Robert F. Overmyer, and Richard H. Truly.

Left: Soviet ASTP cosmonauts (left to right) Dzhanibekov, Andreyev, Romanenko, Ivanchenkov, Rukavishnikov, Filipchenko, Kubasov and Leonov. Right: American ASTP astronauts (left to right) Crippen, Overmyer, Truly, Bobko, Slayton, Stafford, Brand, Lousma, Evans and Bean.

Credits: RKK Energiya.

By December 1974, ASTP development was well underway with meetings between American and Soviet managers, engineers and crewmembers taking place at regular intervals in both countries. Because the Apollo and Soyuz vehicles operated at different cabin pressures and atmospheric composition, the American side built a special docking module that acted as an airlock during the crew transfers between the two spacecraft. The Soviets made additional modifications to the environmental control system of the Soyuz, which they tested during two uncrewed flights – Cosmos 638, launched April 3, 1974, and Cosmos 672, launched Aug. 12, 1974. As an additional safety measure, the Soviets decided to fly a rehearsal mission for their half of ASTP with the second prime crew aboard an identical spacecraft.

Left: Soyuz 16 cosmonauts Filipchenko (left) and Rukavishnikov outside the Soyuz simulator in Star City. Middle: Rukavishnikov (foreground) and Filipchenko inside the Soyuz simulator. Right: Backup Soyuz 16 crew Andreyev (left) and Dzhanibekov during training in Star City.

Credits: RKK Energiya.

On Dec. 2, 1974, Soyuz 16 blasted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan with Filipchenko and Rukavishnikov aboard. Shortly after the launch, the Soviets notified Lunney and provided him with Soyuz 16’s orbital parameters so that NASA’s Spaceflight Tracking Data Network could begin tracking the spacecraft, as they would during the actual joint flight. For the next six days, Filipchenko and Rukavishnikov and Soviet ground controllers executed the flight plan as if during the actual ASTP mission. All tests of the upgraded life support systems performed very well, with the crew changing the internal pressure of the spacecraft. The Soviets had mounted a docking ring that simulated the Apollo side of the docking interface and all tests of that system, including an emergency pyrotechnic separation, proved successful. Bushuyev briefed Lunney on the progress of the mission during telephone conversations and provided a full report to the American team during the joint meetings in Houston in January 1975. Filipchenko and Rukavishnikov landed on the steppe of Kazakhstan on Dec. 8, wrapping up the six-day dress rehearsal for ASTP. Five days later, the two cosmonauts and Soviet managers including Bushuyev held a press conference in Star City outside of Moscow. In a change from previous Soviet practice, reporters had the opportunity to directly ask the cosmonauts questions, in a successful checkout of public affairs protocols for ASTP. Both Filipchenko and Rukavishnikov, veterans of previous Soyuz missions, praised the improvements made to the spacecraft. The successful flight of Soyuz 16 raised optimism about the outcome of the joint mission, just seven months away.

Left: Patch for the Soyuz 16 mission. Middle: Launch of Soyuz 16 from Baykonur. Right: Soyuz 16 descending on its parachute moments before touchdown. Credits: RKK Energiya.

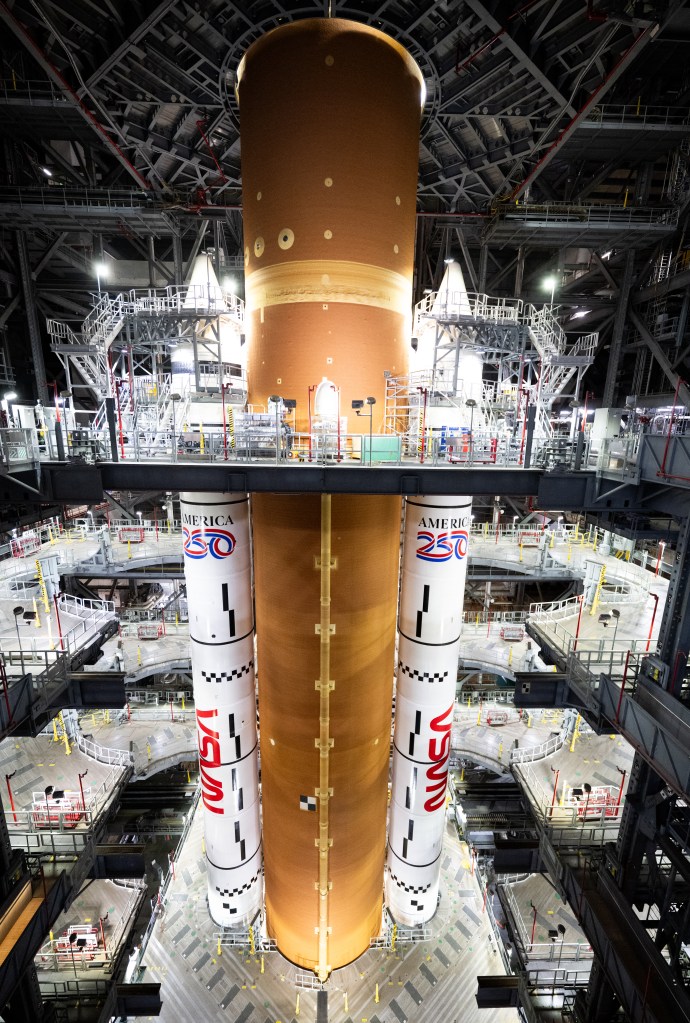

At the time of the Soyuz 16 mission, preparations for ASTP in the United States included readying the Apollo spacecraft and the Saturn 1B rocket at the Kennedy Space Center. The command and service modules arrived from the Rockwell International plant in Downey, California, on Sept. 8, 1974, by C-5A Galaxy cargo plane. The sign on the shipping container bore the legend “From A to Soyuz – Apollo/Soyuz – Last and the Best.” Workers towed the modules to the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building for inspection and checkout. The prime crew of Stafford, Brand, and Slayton conducted vacuum chamber tests with the spacecraft in mid-January 1975. The first and second stages of the Saturn 1B had arrived at Kennedy in April 1974 and November 1972, respectively. Stacking of the rocket on the Mobile Launch Platform in the cavernous Vehicle Assembly Building began in January 1975.

Left: Workers prepare the ASTP Apollo Command Module for testing after its arrival at KSC. Middle: First stage of the ASTP Saturn 1B prior to stacking on the Mobile Launch Platform. Right: ASTP Saturn 1B stacked on the MLP in the VAB.

To be continued…