The 13th flight of the space shuttle program and the sixth of Challenger, STS-41G holds many distinctions. As the first mission focused almost entirely on studying the Earth, it deployed a satellite, employed multiple instruments, cameras, and crew observations to accomplish those goals. The STS-41G crew set several firsts, most notably as the first seven-member space crew. Other milestones included the first astronaut to make a fourth shuttle flight, the first and only astronaut to fly on Challenger three times and on back-to-back missions on any orbiter, the first crew to include two women, the first American woman to make two spaceflights, the first American woman to conduct a spacewalk, and the first Canadian and the first Australian-born American to make spaceflights.

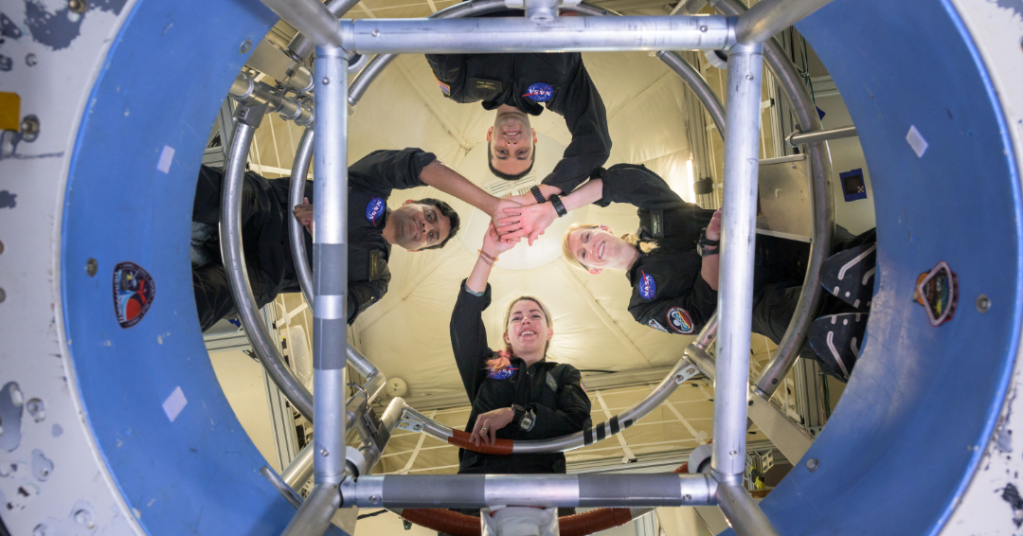

Left: The STS-41G crew patch. Right: The STS-41G crew of Jon A. McBride, front row left, Sally K. Ride, Kathryn D. Sullivan, and David C. Leestma; Paul D. Scully-Power, back row left, Robert L. Crippen, and Marc Garneau of Canada.

In November 1983, NASA named the five-person crew for STS-41G, formerly known as STS-17, then planned as a 10-day mission aboard Columbia in August 1984. When assigned to STS-41G, Commander Robert L. Crippen had already completed two missions, STS-1 and STS-7, and planned to command STS-41C in April 1984. On STS-41G, he made a record-setting fourth flight on a space shuttle, and as it turned out the first and only person to fly aboard Challenger three times, including back-to-back missions. Pilot Jon A. McBride, and mission specialists Kathryn D. Sullivan from the Class of 1978 and, David C. Leestma from the Class of 1980, made their first flights into space. Mission specialist Sally K. Ride made her second flight, and holds the distinction as the first American woman to return to space, having flown with Crippen on STS-7. The flight marked the first time that two women, Ride and Sullivan, flew in space at the same time. In addition, Sullivan holds the honor as the first American woman to conduct a spacewalk and made her second flight and holds the distinction as the first American woman to return to space, having flown with Crippen on STS-7. The flight marked the first time that two women, Ride and Sullivan, flew in space at the same time. In addition, Sullivan holds the honor as the first American woman to conduct a spacewalk, and Leestma as the first of the astronaut Class of 1980 to make a spaceflight.

Columbia’s refurbishment following STS-9 ran behind schedule and could not meet the August launch date, so NASA switched STS-41G to the roomier and lighter weight Challenger. This enabled adding crew members to the flight. In February 1984, NASA and the Canadian government agreed to fly a Canadian on an upcoming mission in recognition for that country’s major contribution to the shuttle program, the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robotic arm. In March, Canada named Marc Garneau as the prime crewmember with Robert B. Thirsk as his backup. NASA first assigned Garneau to STS-51A, but with the switch to Challenger transferred him to the STS-41G crew. On June 1, NASA added Australian-born and naturalized U.S. citizen Paul D. Scully-Power, an oceanographer with the Naval Research Laboratory who had trained shuttle crews in recognizing ocean phenomena from space, to the mission rounding out the seven-person crew, the largest flown to that time. Scully-Power has the distinction as the first person to launch into space sporting a beard.

Left: Space shuttle Challenger returns to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft following the STS-41C mission. Middle: The Earth Resources Budget Satellite during processing at KSC for STS-41G. Right: Technicians at KSC process the Shuttle Imaging Radar-B for the STS-41G mission.

The STS 41G mission carried a suite of instruments to study the Earth. The Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS), managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, contained three instruments, including the Stratospheric Aerosol and Gas Experiment-2 (SAGE-2), to measure solar and thermal radiation of the Earth to better understand global climate changes. NASA’s Office of Space and Terrestrial Applications sponsored a cargo bay-mounted payload (OSTA-3) consisting of four instruments. The Shuttle Imaging Radar-B (SIR-B), managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and an updated version of SIR-A flown on STS-2, used synthetic aperture radar to support investigations in diverse disciplines such as archaeology, geology, cartography, oceanography, and vegetation studies. Making its first flight into space, the 900-pound Large Format Camera (LFC) took images of selected Earth targets on 9-by-18-inch film with 70-foot resolution. The Measurement of Air Pollution from Satellites (MAPS) experiment provided information about industrial pollutants in the atmosphere. The Feature Identification and Location Experiment (FILE) contained two television cameras to improve the efficiency of future remote sensing equipment. In an orbit inclined 57 degrees to the Equator, the instruments aboard Challenger could observe more than 75% of the Earth’s surface.

The Orbital Refueling System (ORS), managed by NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, while not directly an Earth observation payload, assessed the feasibility of on-orbit refueling of the Landsat-4 remote sensing satellite, then under consideration as a mission in 1987, as well as Department of Defense satellites not designed for on-orbit refueling. In the demonstration, the astronauts remotely controlled the transfer of hydrazine, a highly toxic fuel, between two tanks mounted in the payload bay. During a spacewalk, two crew members simulated connecting the refueling system to a satellite and later tested the connection with another remotely controlled fuel transfer. Rounding out the payload activities, the large format IMAX camera made its third trip into space, with footage used to produce the film “The Dream is Alive.”

Four views of the rollout of space shuttle Challenger for STS-41G. Left: From inside the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). Middle left: From Firing Room 2 of the Launch Control Center (LCC). Middle right: From the crawlerway, with the LCC and the VAB in the background. Right: From atop the VAB.

Left: The STS-41G astronauts answer reporters’ questions at Launch Pad 39A during the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test. Right: The STS-41G crew leaves crew quarters and prepares to board the Astrovan for the ride to Launch Pad 39A for liftoff.

Following the STS-41C mission, Challenger returned to KSC from Edwards Air Force Base in California on April 18. Workers in KSC’s Orbiter Processing Facility refurbished the orbiter and changed out its payloads. Rollover to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) took place on Sept. 8 and after workers stacked Challenger with its External Tank and Solid Rocket Boosters, they rolled it out of the VAB to Launch Pad 39A on Sept. 13. Just two days later, engineers completed the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test, a final dress rehearsal before the actual countdown and launch, with the astronaut crew participating as on launch day. They returned to KSC on Oct. 2 to prepare for the launch three days later.

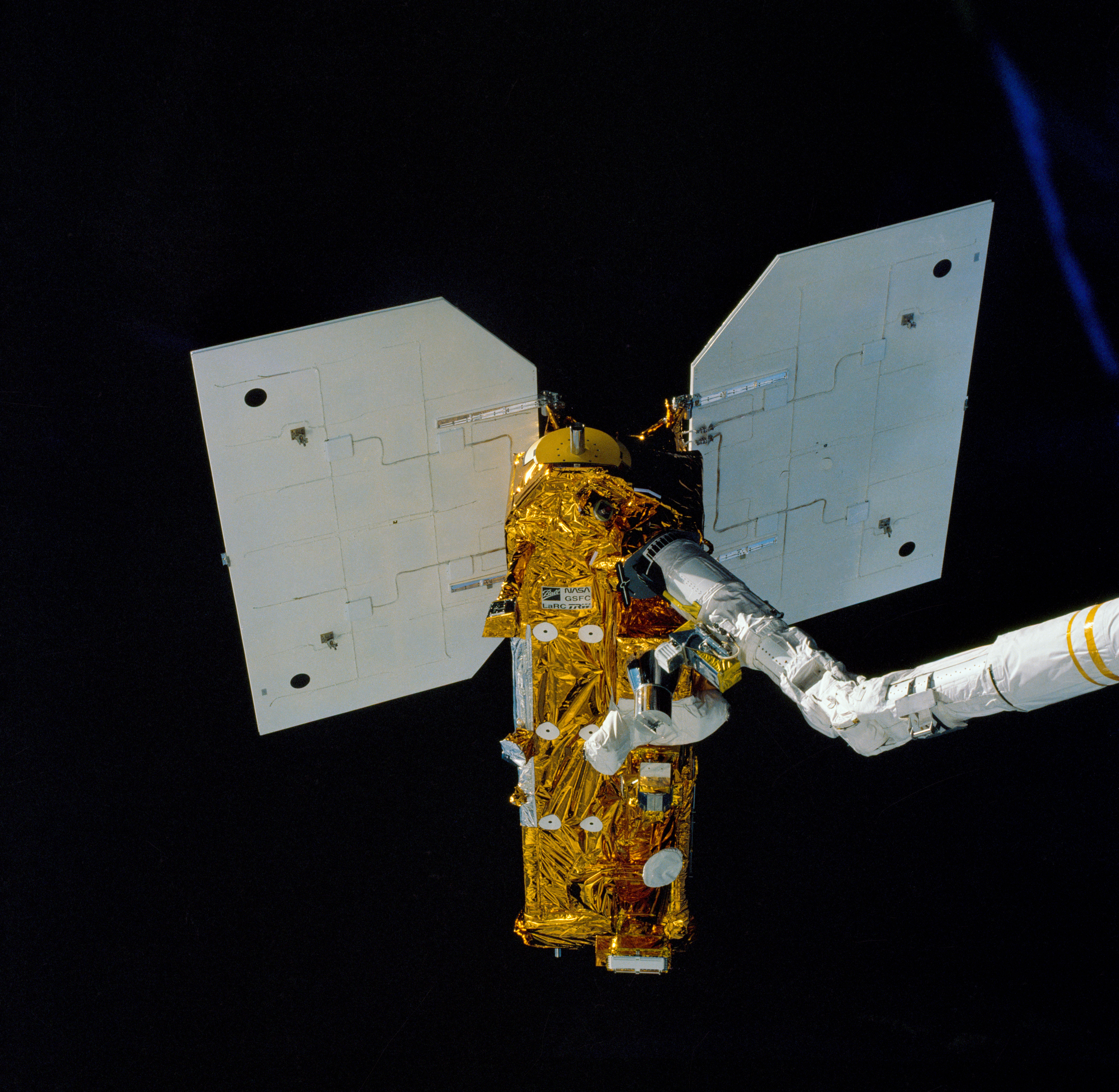

Left: Liftoff of space shuttle Challenger on the STS-41G mission. Middle: Distant view of Challenger as it rises through the predawn skies. Right: The Earth Resources Budget Satellite just before the Remote Manipulator System released it.

Space shuttle Challenger roared off Launch Pad 39A at 7:03 a.m. EDT, 15 minutes before sunrise, on Oct. 5, 1984, to begin the STS-41G mission. The launch took place just 30 days after the landing of the previous mission, STS-41D. That record-breaking turnaround time between shuttle flights did not last long, as the launch of Discovery on STS-51A just 26 days after Challenger’s landing set a new record on Nov. 8.

Eight and a half minutes after liftoff, Challenger and its seven-member crew reached space and shortly thereafter settled into a 218-mile-high orbit, ideal for the deployment of the 5,087-pound ERBS. The crew noted that a 40-inch strip of Flexible Reusable Surface Insulation (FRSI) had come loose from Challenger’s right-hand Orbiter Maneuvering System (OMS) pod, presumably lost during launch. Mission Control determined that this would not have any impact during reentry. Ride grappled the ERBS with the shuttle’s RMS but when she commanded the satellite to deploy its solar arrays, nothing happened. Mission Control surmised that the hinges on the arrays had frozen, and after Ride oriented the satellite into direct sunlight and shook it slightly on the end of the arm, the panels deployed. She released ERBS about two and a half hours late and McBride fired Challenger’s steering jets to pull away from the satellite. Its onboard thrusters boosted ERBS into its operational 380-mile-high orbit. With an expected two-year lifetime, it actually operated until October 14, 2005, returning data about how the Earth’s atmosphere absorbs and re-radiates the Sun’s energy, contributing significant information about global climate change.

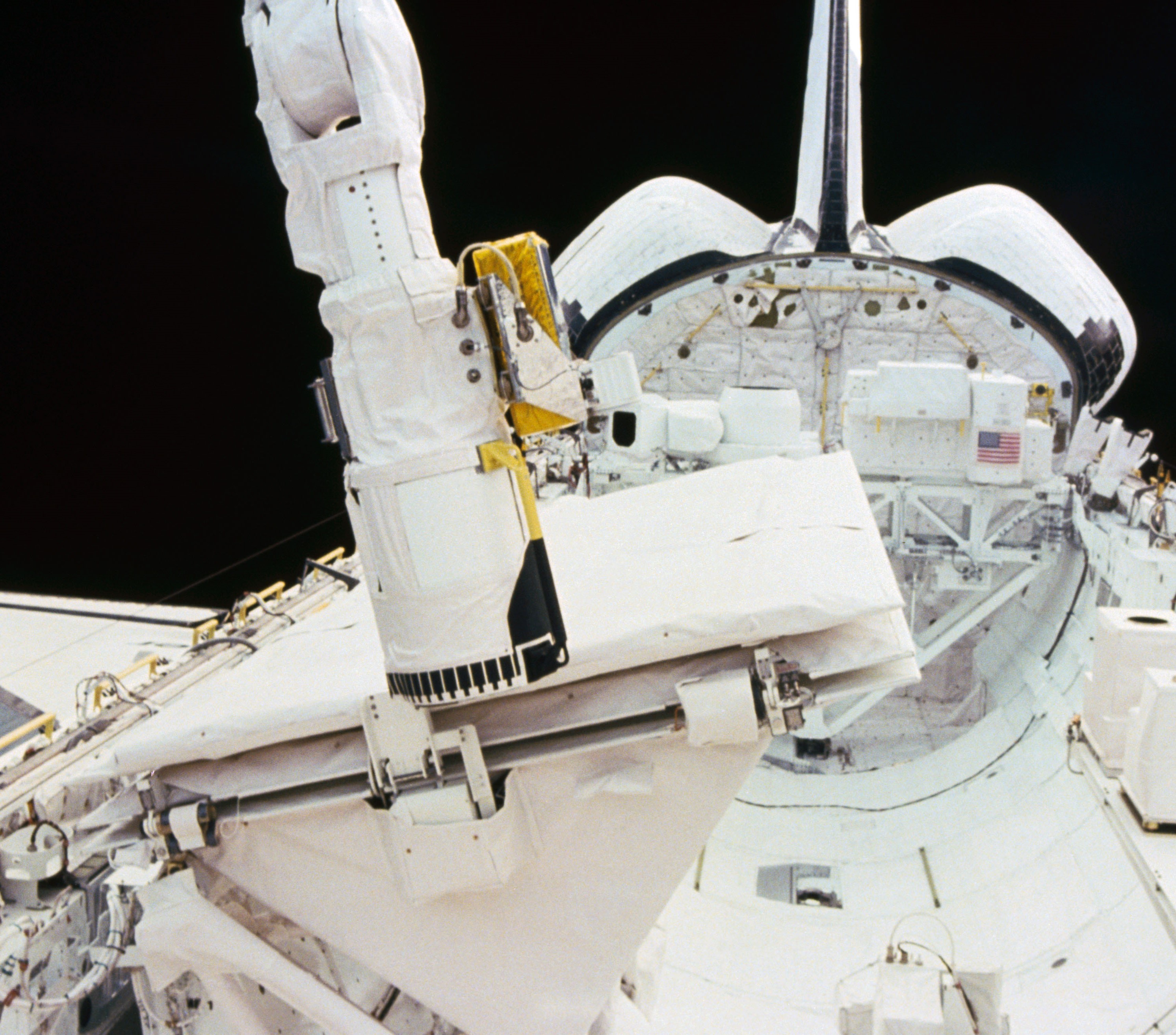

Left: The SIR-B panel opens in Challenger’s payload bay. Right: Jon A. McBride with the IMAX large format camera in the middeck.

Near the end of their first day in space, the astronauts opened the panels of the SIR-B antenna and activated it, also deploying the Ku-band antenna that Challenger used to communicate with the Tracking and Data Relay System (TDRS) satellite. The SIR-B required a working Ku-band antenna to downlink the large volume of data it collected, although it could store a limited amount on onboard tape recorders. But after about two minutes, the data stream to the ground stopped. One of the two motors that steered the Ku antenna failed and it could no longer point to the TDRS satellite. Mission Control devised a workaround to fix the Ku antenna in one position and steer the orbiter to point it to the TDRS satellite and downlink the stored data to the ground. Challenger carried sufficient fuel for all the maneuvering, but the extra time for the attitude changes resulted in achieving only about 40% of the planned data takes. The discovery of the 3,000-year-old lost city of Ubar in the desert of Oman resulted from SIR-B data, one of many interesting findings from the mission.

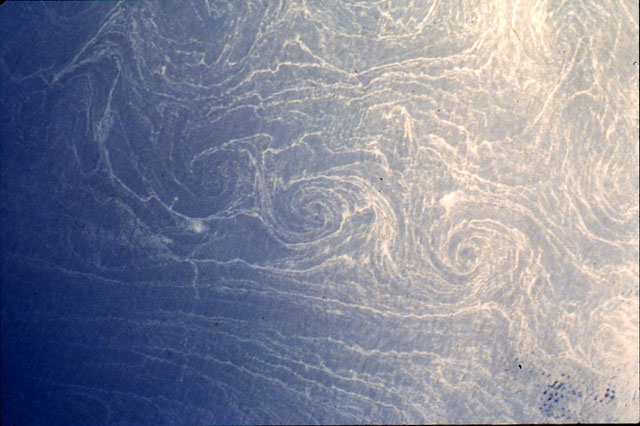

Left: The shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System or robotic arm closes the SIR-B panel. Middle: The patch for Canadian astronaut Marc Garneau’s mission. Right: Spiral eddies in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

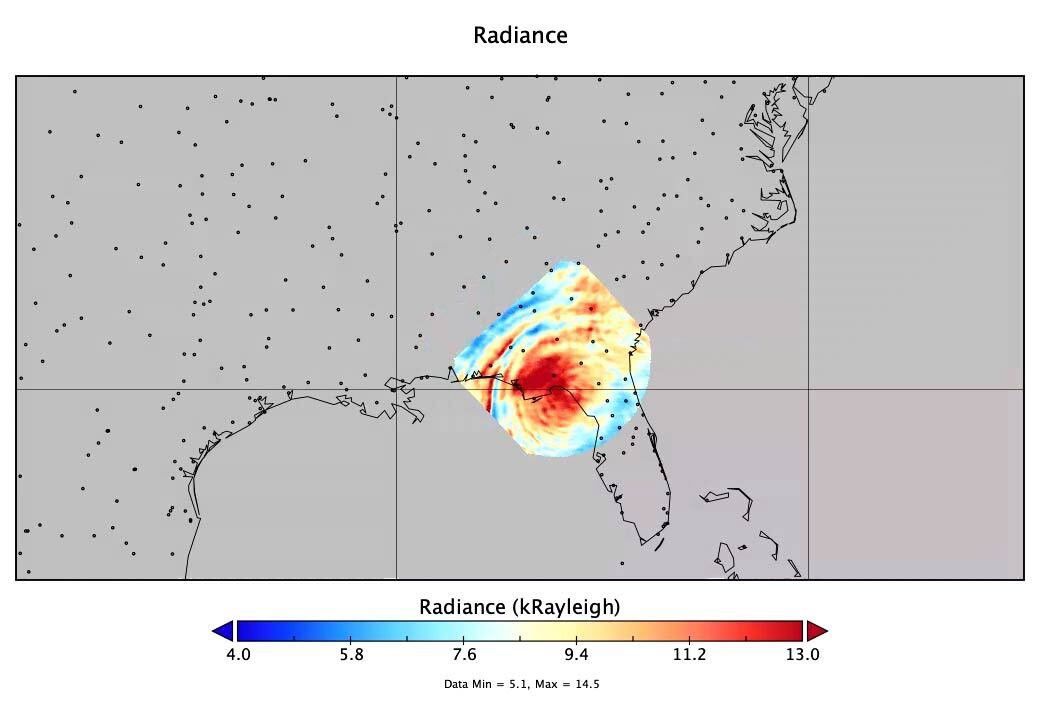

During the second mission day, the astronauts lowered Challenger’s orbit to an intermediate altitude of 151 miles. Flight rules required that the SIR-B antenna be stowed for such maneuvers but the latches to clamp the antenna closed failed to activate. Ride used the RMS to nudge the antenna panel closed. From the orbiter’s flight deck, Leestma successfully completed the first ORS remote-controlled hydrazine fuel transfer. Garneau began working on his ten CANEX investigations related to medical, atmospheric, climatic, materials and robotic sciences while Scully-Power initiated his oceanographic observations. Despite greater than expected global cloud cover, he successfully photographed spiral eddies in the world’s oceans, particularly notable in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

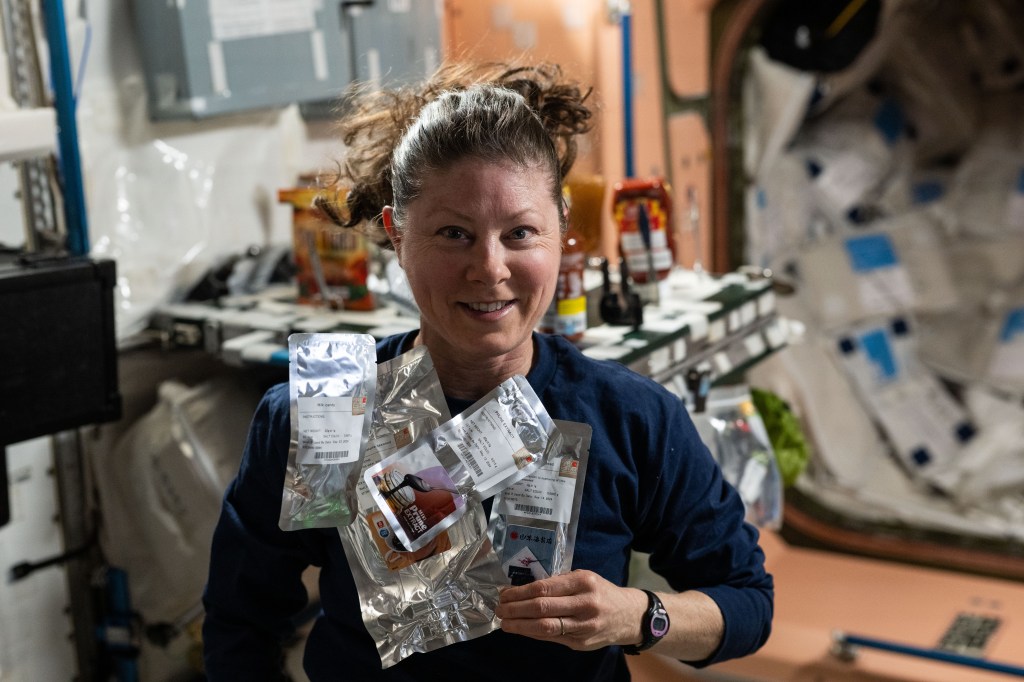

Left: Mission Specialists Kathryn D. Sullivan, left, and Sally K. Ride on Challenger’s flight deck. Right: Payload Specialists Marc Garneau and Paul D. Scully-Power working on a Canadian experiment in Challenger’s middeck.

The third day saw the crew lower Challenger’s orbit to 140 miles, the optimal altitude for SIR-B and the other Earth observing instruments. For the next few days, all the experiments continued recording their data, including Garneau’s CANEX and Scully-Power’s oceanography studies. Leestma completed several scheduled ORS fuel transfers prior to the spacewalk. Preparations for that activity began on flight day 6 with the crew lowering the cabin pressure inside Challenger from the normal sea level 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi) to 10.2 psi. The lower pressure prevented the buildup of nitrogen bubbles in the bloodstreams of the two spacewalkers, Leestma and Sullivan, that could result in the development of the bends. The two verified the readiness of their spacesuits.

Left: David C. Leestma, left with red stripes on his suit, and Kathryn D. Sullivan during their spacewalk. Middle: Leestma, left, and Sullivan working on the Orbital Refueling System during the spacewalk. Right: Sullivan, left, and Leestma peer into Challenger’s flight deck during the spacewalk.

On flight day 7, Leestma and Sullivan, assisted by McBride, donned their spacesuits and began their spacewalk. After gathering their tools, the two translated down to the rear of the cargo bay to the ORS station. With Sullivan documenting and assisting with the activity, Leestma installed the valve assembly into the simulated Landsat propulsion plumbing. After completing the ORS objectives, Leestma and Sullivan proceeded back toward the airlock, stopping first at the Ku antenna where Sullivan secured it in place. They returned inside after a spacewalk that lasted 3 hours and 29 minutes, and the crew brought Challenger’s cabin pressure back up to 14.7 psi.

STS-41G crew Earth observation photographs. Left: Hurricane Josephine in the Atlantic Ocean. Middle: The Strait of Gibraltar. Right: Karachi, Pakistan, and the mouth of the Indus River.

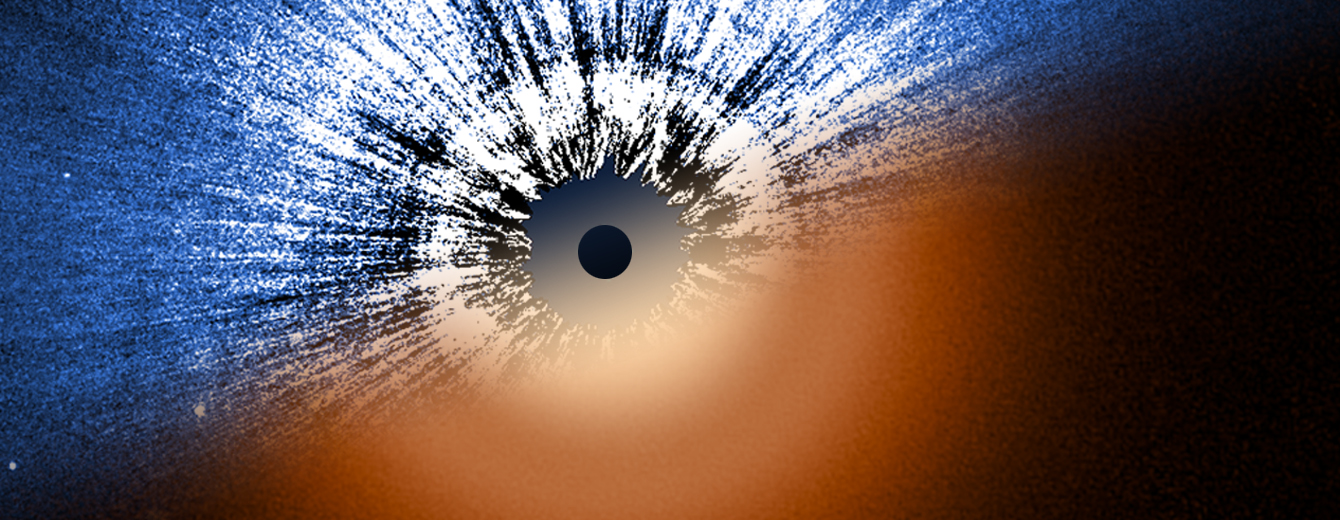

False color image of Montreal generated from SIR-B data.

Left: Traditional inflight photo of the STS-41G crew on Challenger’s flight deck. Right: Robert L. Crippen with the orange glow generated outside Challenger during reentry.

Left: Kathryn D. Sullivan photograph of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida during Challenger’s approach, minutes before touchdown. Middle: Space shuttle Challenger moments before touchdown at N KSC at the end of the STS-41G mission. Right: The crew of STS-41G descends from Challenger after completing a highly successful mission.

During their final full day in space, Challenger’s crew tidied the cabin for reentry and completed the final SIR-B and other Earth observations. On Oct. 13, the astronauts closed the payload bay doors and fired the OMS engines over Australia to begin the descent back to Earth. Because of the mission’s 57-degree inclination, the reentry path took Challenger and its crew over the eastern United States, another Shuttle first. Crippen guided the orbiter to a smooth landing at KSC, completing a flight of 8 days, 5 hours, and 24 minutes, the longest mission of Challenger’s short career. The crew had traveled nearly 3.3 million miles and completed 133 orbits around the Earth.

Left: Missing insulation from Challenger’s right hand Orbiter Maneuvering System pod as seen after landing. Middle: Missing tile from the underside of Challenger’s left wing. Right: Damage to tiles on Challenger’s left wing.

As noted above, on the mission’s first day in space the crew described a missing strip of FRSI from the right-hand OMS pod. Engineers noted additional damage to Challenger’s Thermal Protection System (TPS) after the landing, including several tiles on the underside the vehicle’s left wing damaged and one tile missing entirely, presumably lost during reentry. Engineers determined that the water proofing used throughout the TPS that allowed debonding of the tiles as the culprit for the missing tile. To correct the problem, workers removed and replaced over 4,000 tiles, adding a new water proofing agent to preclude the recurrence of the problem on future missions.

Read recollections of the STS-41G mission by Crippen, McBride, Sullivan, Ride, and Leestma in their oral histories with the JSC History Office. Enjoy the crew’s narration of a video about the STS-41G mission.