Space shuttle Columbia took to the skies on March 22, 1982, for its third trip into space. Astronauts Jack R. Lousma and C. Gordon Fullerton rode the reusable spacecraft on a pillar of fire from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. They continued engineering tests of the orbiter with an emphasis on characterizing its thermal properties. Lousma and Fullerton used the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robotic arm to grapple and lift a payload for the first time. Mission managers extended the planned seven-day mission by one day due to inclement weather at the alternate landing site at Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, the only touchdown at that location in shuttle history.

Left: Official photo of the STS-3 crew of Jack R. Lousma, left, and C. Gordon Fullerton. Right: Official STS-3 crew patch.

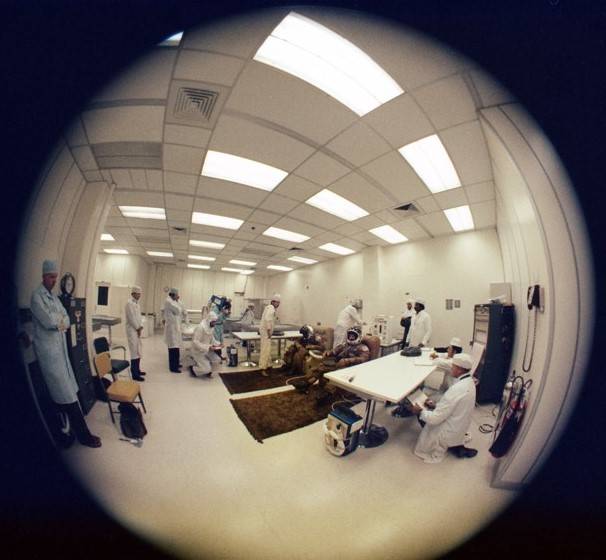

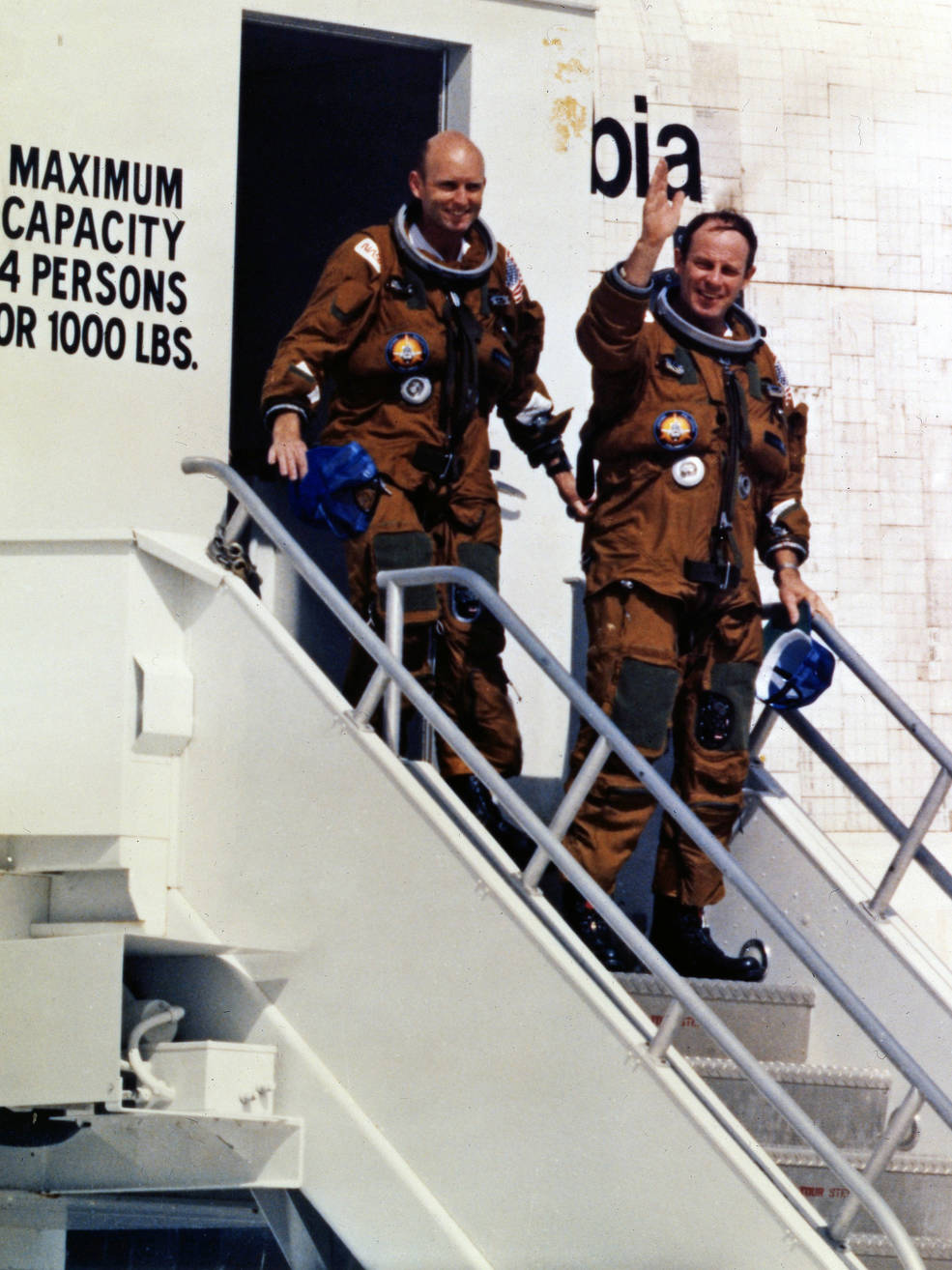

Space shuttle Columbia landed at KSC on Nov. 14, 1981, following the STS-2 mission. Ground crews refurbished the vehicle in what was then record time, and installed on Launch Pad 39A on Feb. 16, 1982. The 73-hour countdown, including several built-in holds, commenced on March 18, with controllers in Firing Room 1 of the Launch Control Center monitoring the activities. Lousma and Fullerton arrived at KSC on March 20 to prepare for the launch two days later. They reviewed the mission plan and practiced landings in the Shuttle Training Aircraft. They awoke before dawn on launch morning, and after the traditional breakfast, they donned their launch and entry pressure suits and took the astronaut van for the ride to the launch pad.

Left: On launch day morning, STS-3 astronauts C. Gordon Fullerton, left, and Jack R. Lousma enjoy the traditional prelaunch breakfast in crew quarters at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Middle: Following breakfast, Fullerton, left, and Lousma don their pressure suits, in this fish-eye view in the suit-up room. Right: Fullerton, left, and Lousma depart crew quarters, accompanied by Chief Astronaut John W. Young, far left, and Director of Flight Operations George W.S. Abbey.

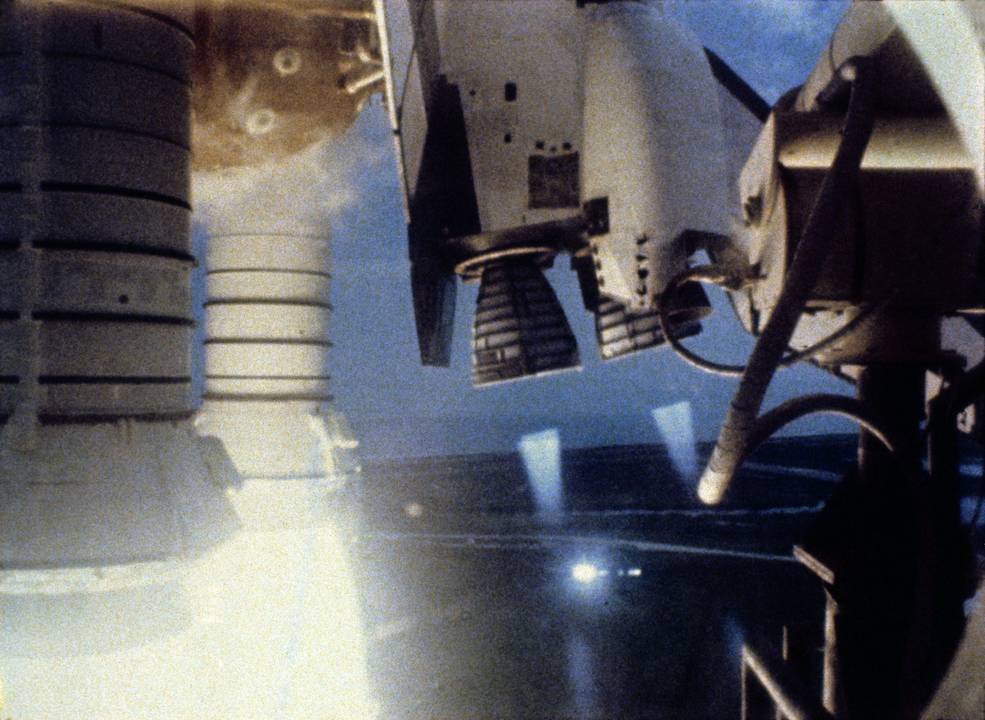

After a one-hour delay, at precisely 11 a.m. EST on March 22, 1982, space shuttle Columbia lifted off from Launch Pad 39A, riding on the thrust of its two solid rocket boosters and its three main engines. As soon as the shuttle cleared the launch tower, control handed over to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. The Ivory Team of flight controllers led by ascent Flight Director Thomas W. “Tommy” Holloway monitored Columbia’s launch, with capsule communicator (capcom) astronaut Terry J. “TJ” Hart relaying milestone events to Lousma and Fullerton aboard the shuttle. About two minutes after liftoff, the two solid rocket boosters were jettisoned, and Columbia continued its ascent on the power of its three main engines. Eight and a half minutes after liftoff, Columbia’s main engines cut off and the large external tank was jettisoned. The space shuttle had reached space but was not yet in orbit, that job left for Columbia’s Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines to complete. The next major task involved opening the orbiter’s payload bay doors to allow the radiators mounted inside them to cool the vehicle. Mission Control gave Lousma and Fullerton a “go” to stay in orbit. They could now remove their launch and entry pressure suits and change into more comfortable flight suits.

Left: Liftoff of STS-3 on Columbia’s third trip to space. Middle: Seconds after liftoff, a view of the two solid rocket boosters and the shuttle’s three main engines. Right: In Firing Room 1 of the Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, James A. Abrahamson, left, NASA Associate Administrator for Space Transportation Systems, congratulates the launch team, as KSC Director Richard G. Smith and NASA Administrator James M. Beggs look on.

One of the first tasks for Lousma and Fullerton involved activating the Office of Space Science-1 (OSS-1) payload, a suite of nine experiments in space plasma physics, solar physics, astronomy, life sciences, and space technology located in Columbia’s payload bay and one in the middeck. In Mission Control, Flight Director Neil B. Hutchinson and his Sliver Team of controllers took over the consoles with astronaut Sally K. Ride serving as the new capcom. The rest of their first day in space passed uneventfully, and Lousma and Fullerton began their first sleep period in space. In Mission Control, the Crystal Team led by Flight Director Harold M. Draughon, including capcom astronaut Steven R. Nagel, took their positions.

Left: View of Columbia’s payload bay, with the shuttle Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robotic arm grappling the Plasma Diagnostics Package (PDP), part of the Office of Space Science-1 payload. Middle: The PDP at the end of the RMS after unberthing from the payload bay, marking the first use of the RMS to grapple and lift a payload. Right: Televised image from the RMS of the missing tiles from Columbia’s nose.

The next morning, the Crystal Team greeted Lousma and Fullerton for their first full day in space with Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again” as the wake-up song. The astronauts reported that several of Columbia’s tiles were missing, notably on the vehicle’s nose. Hutchinson’s Silver Team, with Ride again serving as capcom, resumed their console positions and helped the crew with the first task of the day, powering up the RMS for its first test of the mission. The astronauts fired Columbia’s reaction control system thrusters to see the effect they had on the RMS. They next used the RMS and its elbow camera to downlink to Mission Control an inspection of the orbiter’s nose where they earlier reported the missing tiles. Specialists on the ground analyzed the situation and concluded that the 25 missing tiles would not cause any problems during reentry. Due to the failure of the RMS wrist camera and one of the four payload bay cameras, mission managers decided to delete arm operations with the 850-pound Induced Environmental Contamination Monitor from the task list– the payload flew again on STS-4 and accomplished its objectives on that mission. Instead, Lousma and Fullerton focused their efforts on using an alternate procedure – one that didn’t require the use of the wrist camera – to grapple and move the lighter 350-pound Plasma Diagnostics Package (PDP) to various locations around the payload bay. They conducted operations with the PDP for a total of 20 hours on the mission’s third, fourth, and fifth days. The PDP collected data for an additional 36 hours while stowed on its pallet.

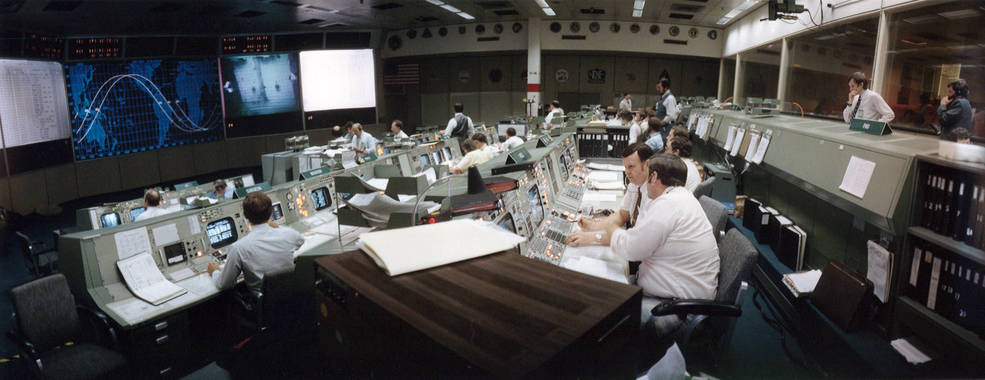

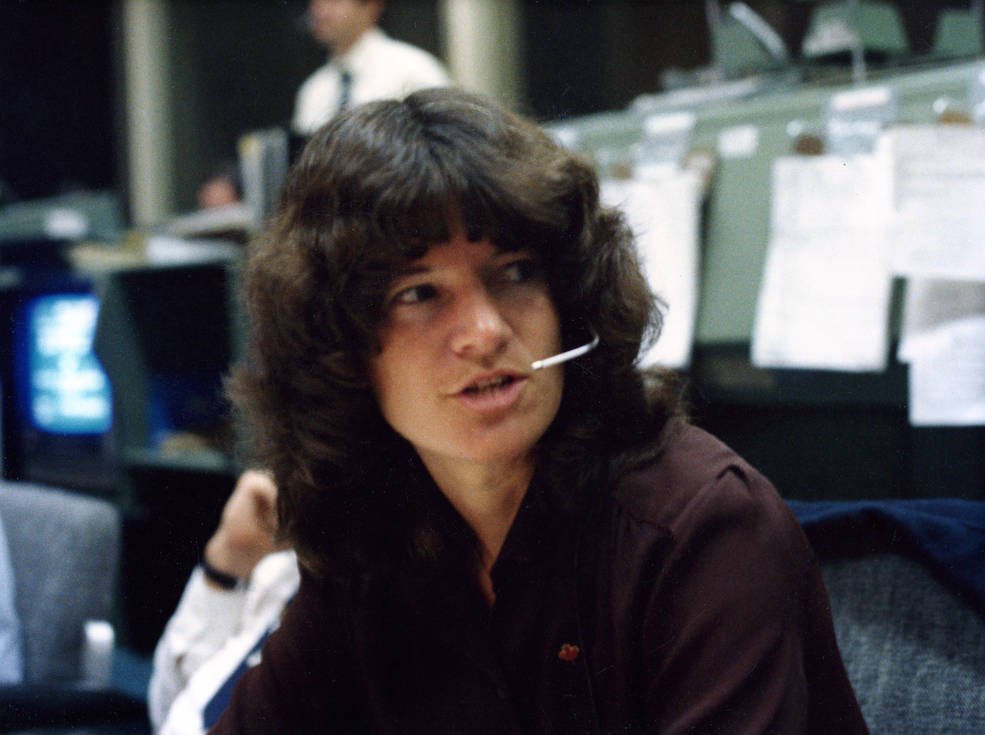

The Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in

Houston during the STS-3 mission.

To ease the astronauts’ workload as they continued to adapt to weightlessness, Mission Control decided to swap the activities for flight days three and four, since day three’s activities included intensive RMS operations. Over the next several days, Lousma and Fullerton continued to execute the flight plan, with only occasional minor glitches and malfunctions. During the mission, to test the orbiter’s thermal responses, they maneuvered Columbia into various attitudes. For 30 hours, Columbia flew with its tail pointed at the Sun, exposing the payload bay to its coldest conditions yet. For 80 hours, they pointed Columbia’s nose toward the Sun, and for 36 hours exposed its open payload bay to the Sun. They also performed several barbecue rolls to passively thermal condition the spacecraft.

Astronauts Jack R. Lousma, left, and C. Gordon Fullerton on the flight deck of

space shuttle Columbia during the STS-3 mission.

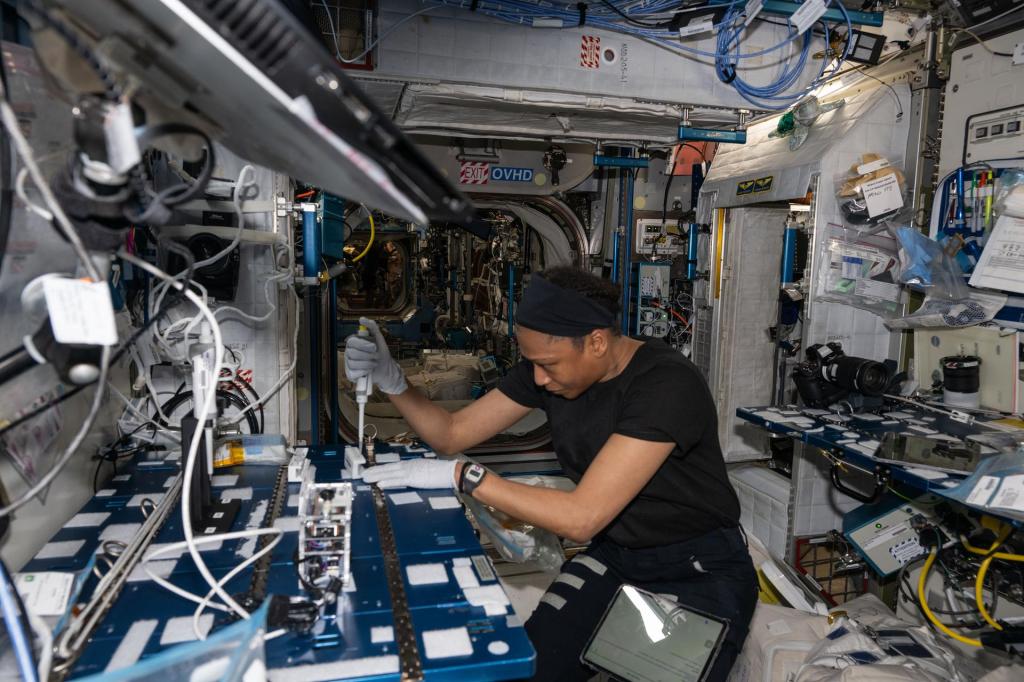

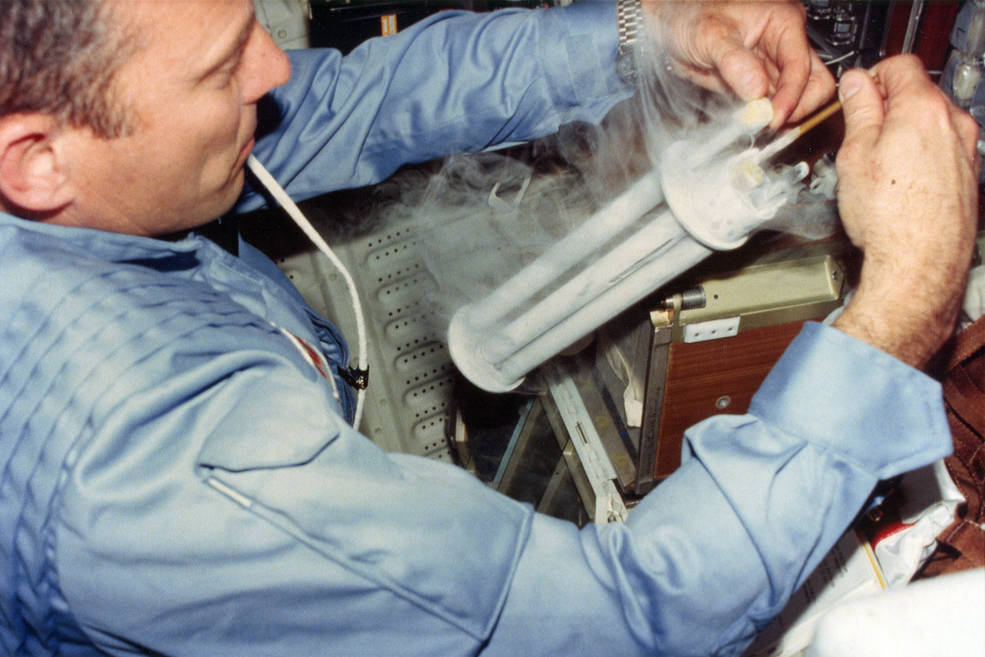

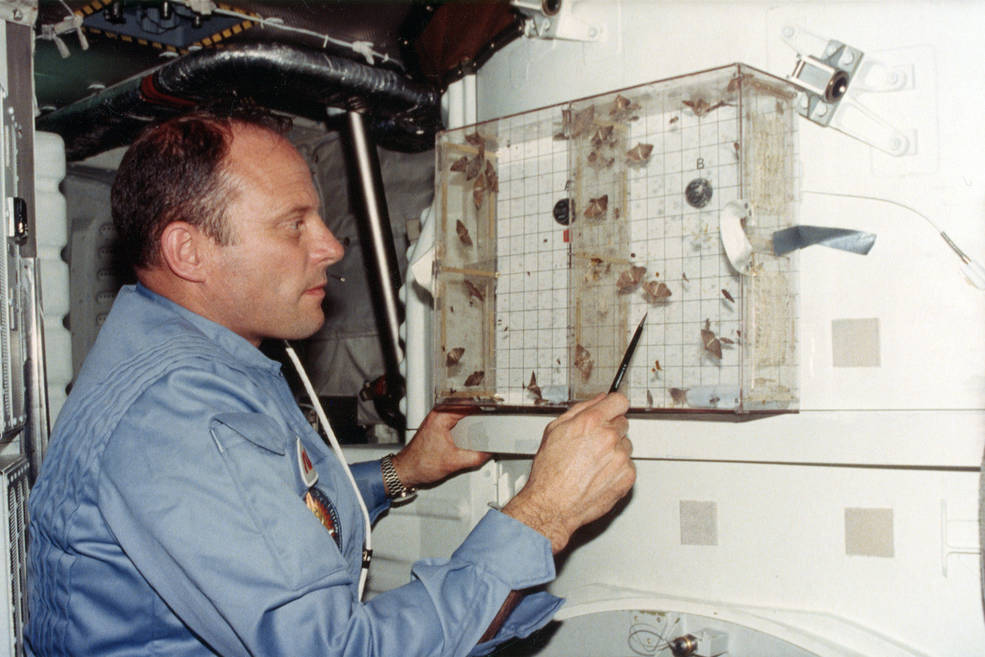

Late on their third day, Lousma and Fullerton broke the record for the longest space shuttle mission, a record they held for a year and a half. For the rest of the mission, they continued to operate several experiments in the middeck, such as the electrophoresis experiment verification test and a plant growth experiment, and monitored the Insects in Flight Motion Study, an experiment carried aboard STS-3 as part of the Shuttle Student Involvement Project for Secondary Schools. The breakdown of the waste collection system, or space toilet, early on the third day caused them the most personal discomfort. They also tested a new treadmill designed by astronaut Dr. William E. Thornton, and reported that it worked well.

Left: Astronaut Jack R. Lousma working with the electrophoresis experiment.

Right: Lousma working with the Insects in Flight Motion Study, an experiment

carried aboard STS-3 as part of the Shuttle Student Involvement Project

for Secondary Schools.

Left: Recovery personnel board a jet to carry them to the alternate landing site

at Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Right: Capsule

communicator astronaut Sally K. Ride talks to the STS-3 crew from Mission

Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Four days before launch, NASA Administrator James M. Beggs decided to change Columbia’s touchdown from the prime landing site at Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California. Torrential spring rains had left the lakebed runway covered with several inches of water that wouldn’t dry in time for the STS-3 landing, planned for March 29. Ground crews transported recovery equipment by two trains to the alternate landing site at Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, while personnel flew in on jets. Lousma and Fullerton suited up for the planned landing, when less than 30 minutes before the scheduled retrofire, mission managers delayed the return by 24 hours when unusually high winds violated landing safety criteria and kicked up the fine gypsum sand at White Sands. With an extra day in space and relatively few scheduled activities, Lousma and Fullerton spent time looking at the Earth, photographing areas of interest.

Four of the Earth observation photographs taken by STS-3 astronauts Jack R. Lousma and C. Gordon Fullerton – Los Angeles, left, White Sands in New Mexico, New Jersey, and the Straits of Gibraltar.

On March 30, for their final wake-up call in space, capcom Nagel greeted Lousma and Fullerton with the patriotic song “This is My Country.” They responded with a recorded medley of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Marine Corps hymns, Fullerton and Lousma’s service branches, respectively. They closed the payload bay doors, donned their pressure suits, and maneuvered Columbia so it was flying tail first. Flight Director Draughon gave them a “go” for the deorbit burn, and they fired Columbia’s OMS engines over Australia for nearly three minutes to drop it out of orbit. Twenty-seven minutes later, Columbia encountered the first tendrils of the Earth’s upper atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet. The heat of reentry caused a sheath of ionized plasma to form around the vehicle, blocking communications for 16 minutes.

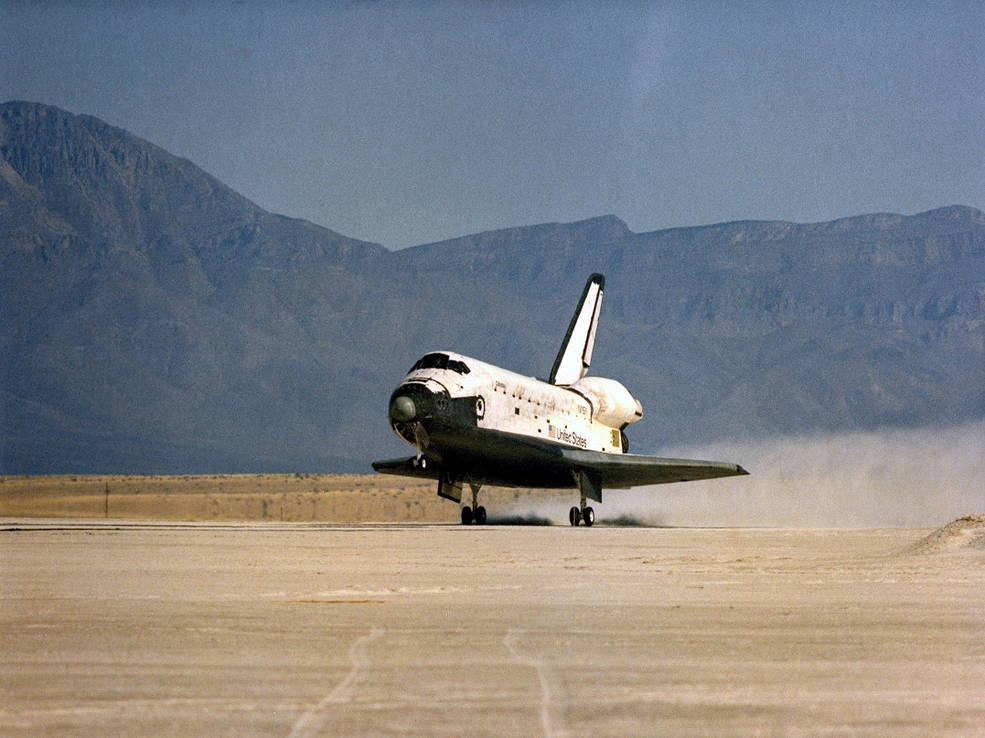

Left: Space shuttle Columbia makes its final approach to Northrup Strip at the White

Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Right: Touchdown! Columbia lands on

the runway at Northrup Strip.

Columbia crossed the coast of Baja California, Mexico, heading in a northeasterly direction, crossing into the United States over Arizona, flying over Phoenix at 150,000 feet altitude, and finally into New Mexico. At 20,000 feet, Columbia made a right hand turn toward Northrup Strip’s runway 17. Fifty feet above the runway, Fullerton lowered Columbia’s landing gear, and Lousma brought the spacecraft down for a smooth touchdown at 9:05 a.m. MST. After rollout, Columbia came to a stop, having completed a flight of 8 days, 4 minutes, and 46 seconds, and circled the Earth 129 times.

Left: Wheels stop! Space shuttle Columbia’s third trip to space is successfully completed. Middle: STS-3 astronauts C. Gordon Fullerton, left, and Jack R. Lousma exit Columbia following the successful landing. Right: Fullerton, left, and Lousma perform the traditional walkaround of Columbia with Director of Flight Operations George W.S. Abbey.

Left: At Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, astronauts Jack R. Lousma, left, and C. Gordon Fullerton address an audience assembled to welcome them home. Right: At NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, STS-1 Commander and Chief of the Astronaut Office John W. Young, left, Director of Flight Operations George W.S. Abbey, STS-2 Commander Joe H. Engle, STS-4 Pilot Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield, STS-3 Pilot C. Gordon Fullerton, STS-3 Commander Jack R. Lousma, STS-4 Commander Thomas K. “TK” Mattingly, and STS-2 Pilot Richard H. Truly debrief the STS-3 mission.

About 6,000 spectators and 1,600 media and invited guests, including the astronauts’ families, watched Columbia’s landing at the remote Northrup Strip. After a welcome home ceremony, officials transported Lousma and Fullerton to nearby Holloman AFB where they boarded a plane to Houston’s Ellington Field. The next day, they began a series of debriefings, describing in great detail all aspects of their mission. On April 13, Lousma and Fullerton held a press conference at JSC, where they showed a film of their mission and answered reporters’ questions. Lousma compared the reentry to a “great toboggan run,” and noted the flight ranked as “the great adventure of my life.” Although Fullerton kidded that his only function involved lowering the shuttle’s landing gear, he accomplished many firsts, including the first person to grapple a payload with the RMS.

Left: Ground crews at Northrup Strip at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico prepare to lift space shuttle Columbia in the Mate Demate Device (MDD). Middle: Workers lowering Columbia onto the back of the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) in the MDD at Northrup Strip. Right: Columbia atop the SCA takes off from Northrup Strip for the ferry flight back to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Left: Space shuttle Columbia atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) touches down at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: Workers lift Columbia from the SCA in the Mate Demate Device at KSC. Right: Ground crews tow Columbia from the runway to the Orbiter Processing Facility at KSC

to begin preparing it for its next flight.

Meanwhile, ground crews at Northrup Strip towed Columbia from the runway to a service area to begin preparing it for its cross country trip back to KSC. On April 5, after workers mounted it atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified Boeing-747, Columbia left Northrup and, after an overnight refueling stop at Barksdale AFB in Louisiana where a crowd estimated at 100,000 turned out to view the space shuttle, arrived at KSC the next day, just one week after its landing in New Mexico. On April 7, workers towed it to KSC’s Orbiter Processing Facility to begin preparations for its next mission, STS-4, planned for June 1982.