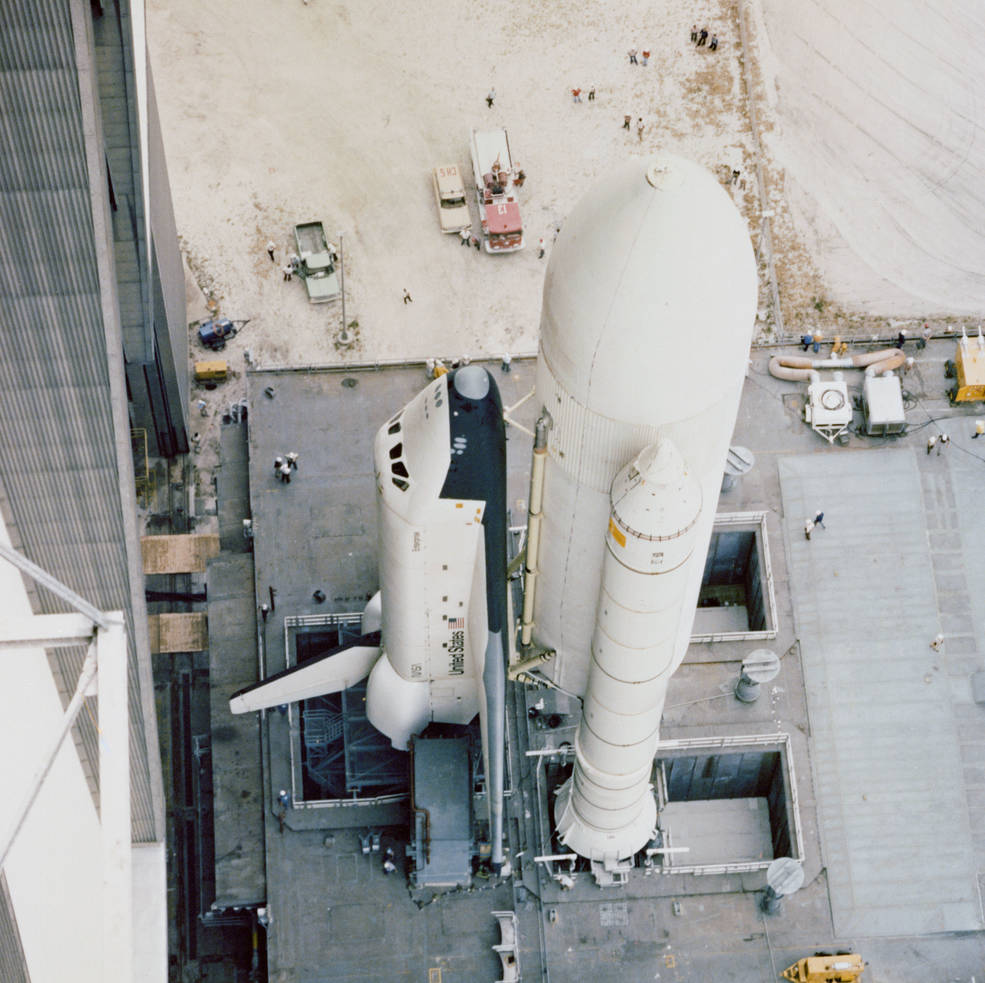

May 1, 1979: Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida received its first visitor since the launch of the Skylab space station six years earlier. The Space Shuttle Enterprise, the first of a new kind of spacecraft, made the slow 3.5-mile trek from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to the launch pad, atop the same Mobile Transporter that had carried Saturn V’s during the Apollo Program.

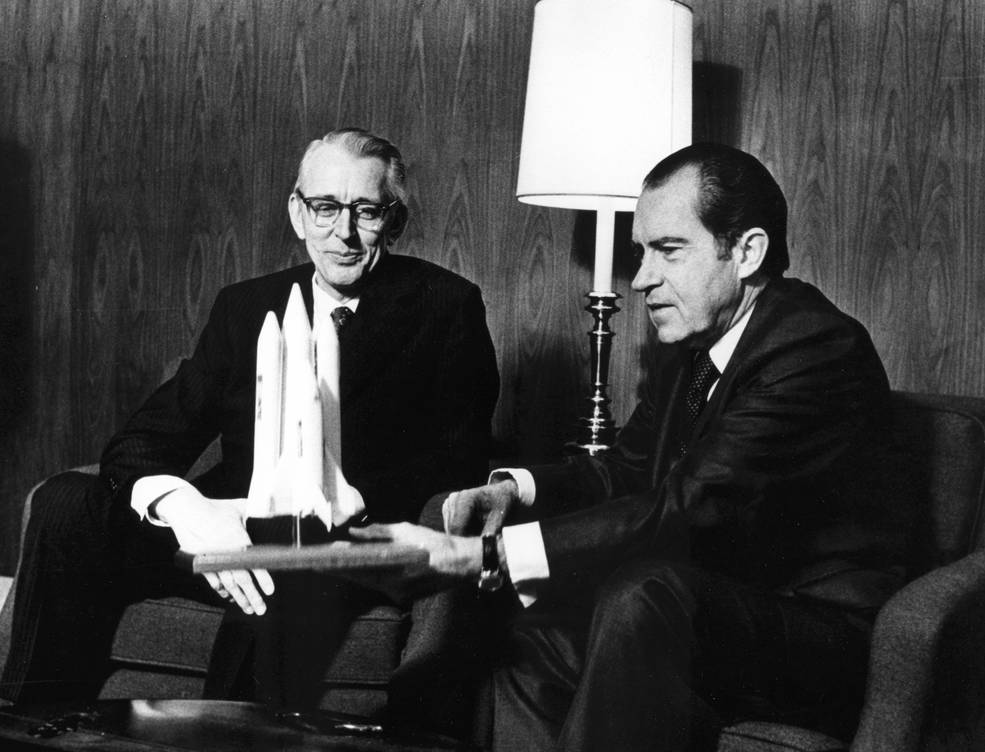

The story of Enterprise began on Jan. 5, 1972, when President Richard M. Nixon announced his decision for NASA to build the Space Shuttle, formally called the Space Transportation System (STS), stating that “it would revolutionize transportation into near space.” NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher hailed the President’s decision as “an historic step in the nation’s space program,” adding that it would change what humans can accomplish in space. Once Congress authorized the funds, NASA on July 26 awarded the contract to the North American Rockwell Corporation of Downey, California, to begin construction of the first vehicles. Manufacture of the first components of Orbital Vehicle-101 (OV-101) at Rockwell’s Downey, California, plant began on June 4, 1974.

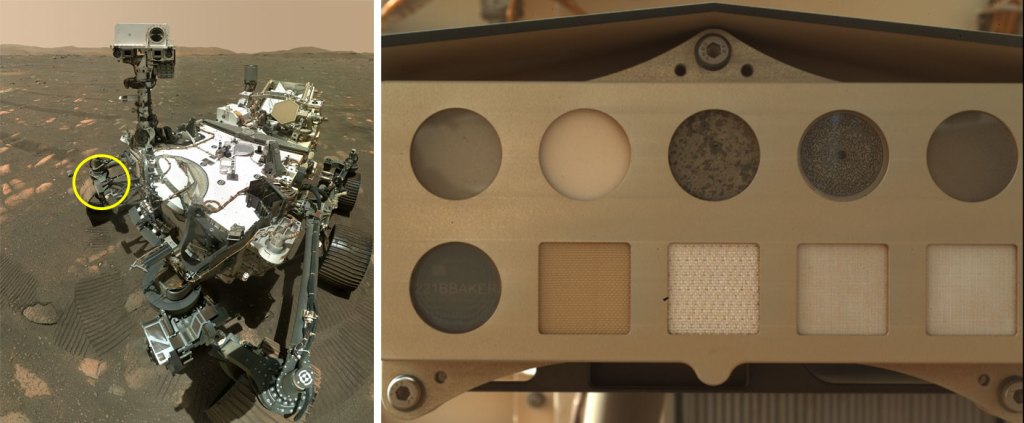

Left: NASA Administrator Fletcher (left) and President Nixon presenting the Space Shuttle. Right: Enterprise under construction in 1976.

NASA originally chose the name Constitution for OV-101, the first Space Shuttle vehicle designed not to fly in space but to be used in ground and aerial tests within the Earth’s atmosphere. A determined write-in campaign by fans of the science fiction TV series Star Trek convinced NASA to rename this first vehicle Enterprise, after the fictional starship made famous by the show. That was the name painted on the vehicle’s side when it made its public rollout at Rockwell’s Palmdale, California, facility, on September 17, 1976. Several Star Trek cast members as well as the show’s creator were on hand to witness the event, accompanied by NASA Administrator Fletcher and the four astronauts who were scheduled to conduct the aerial tests with Enterprise – Fred W. Haise, C. Gordon Fullerton, Joe H. Engle, and Richard C. Truly.

In January 1977, workers trucked Enterprise 36 miles overland from Palmdale to NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, now Armstrong Flight Research Center, at Edwards Air Force Base in California, where they placed it on the back of the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), a modified Boeing 747. The duo began taxi runs in February, followed by the first captive inactive flight later that month. The first captive active flight that included a crew aboard the shuttle took place in June, and Enterprise made its first independent flight on Aug. 12 with Haise and Fullerton at the controls. Four additional approach and landing flights were completed by October.

Left: NASA Administrator Fletcher (left) accompanied by several cast members and creator of the TV series

Star Trek at Enterprise’s rollout. Right: Astronauts Fullerton, Haise, Engle, and Truly pose in front of Enterprise

on the day of its rollout.

Left: Crew patch for the Approach and Landing Tests. Right: Space Shuttle Enterprise moments after release

from the back of the SCA during the first ALT flight.

In March 1978, Enterprise was flown to the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, where workers mated it with an External Tank (ET) and inert Solid Rocket Boosters (SRB) for the first time and installed the combined stack in the Dynamic Structural Test Facility. For the next year, engineers conducted a series of vibration tests on the combined vehicle, simulating conditions expected during an actual launch.

Left: Enterprise atop its SCA touches down on the runway at KSC. Middle: Workers removing Enterprise from the SCA in the MDD.

Right: Workers towing Enterprise into the VAB or OPF.

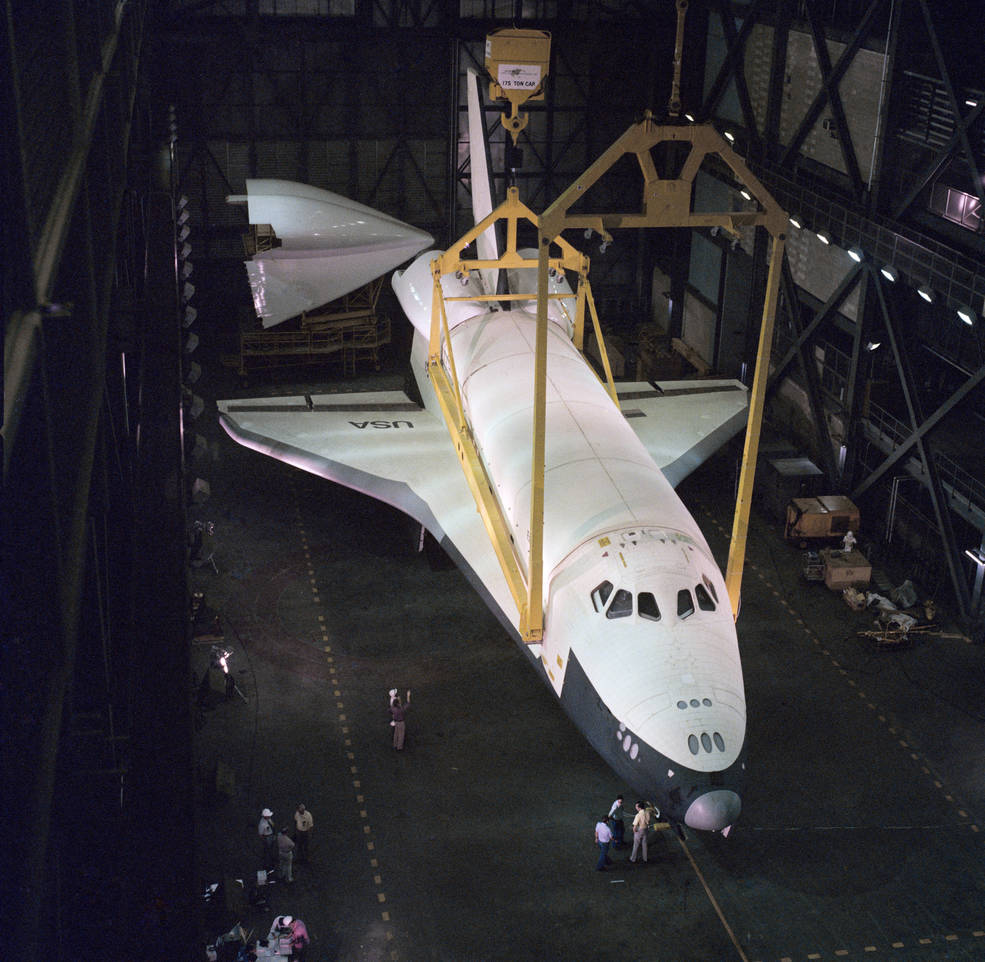

Following the year-long series of tests at Marshall, on April 10, 1979, NASA ferried Enterprise atop its SCA to KSC (its sister ship Columbia, the first shuttle destined for orbital flight, had arrived there just two weeks earlier). The SCA/Enterprise vehicle remained on display at the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) for five days to give KSC employees, their families, and the general public a chance to view the new reusable spacecraft. More than 75,000 people took the opportunity to see the space shuttle. Workers at the SLF then removed the orbiter from the back of the SCA in the Mate-Demate Device (MDD), and towed it into High Bay 3 of the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) where on April 25 they completed attaching it to an ET and inert SRBs on a Mobile Launch Platform (MLP) repurposed from carrying Saturn rockets. These processes enabled verification of towing, assembly, and checkout procedures.

Left: Workers in the VAB prepare to lift Enterprise. Middle: Enterprise in the vertical position.

Right: Enterprise being lowered for attachment to the External Tank.

Roll out to Launch Pad 39A occurred on May 1, and again KSC employees and their families were invited to view the event. With Enterprise mated to its ET and SRBs perched on the MLP, a total mass of about 11 million pounds, and riding atop the Mobile Transporter, technicians drove the stack at varying speeds to determine the optimum velocity to minimize vibration stress on the vehicle. The rollout process took about eight hours to complete. Once at the pad, engineers used Enterprise to conduct fit checks and to validate launch pad procedures. The most critical step was a countdown demonstration test during which the ET was filled with super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. A significant discovery that ice built up at the top of the ET during this process led to the addition of the gaseous oxygen vent hood (familiarly known as the “beanie cap”) to the launch pad facility and a procedure to retract it just a few minutes before liftoff. This prevented the dangerous buildup of ice during the countdown and was perhaps Enterprise’s greatest contribution as a test vehicle during its time at the launch pad.

Left: Enterprise exiting the VAB. Middle: Enterprise on its MLP during the rollout to the pad. Right: Enterprise at Pad 39A.

After three months of fit checks and testing, Enterprise was rolled back from Pad 39A to High Bay 1 in the VAB on July 23. The activities conducted at the pad were instrumental in paving the way for its sister ship Columbia to make its first launch in 1981. John Bell, who managed the activities at JSC said of the test program, “Overall, it was a very successful venture and well worth it.” Pad 39A Site Manager John “Tip” Talone added, “Having [Enterprise] out here really saved the program a lot of time in getting things ready for [Columbia].” In the VAB, workers removed Enterprise from its ET on July 25 and towed it to the SLF on Aug. 3 where it awaited the arrival of the SCA. The ferry flight back to Dryden took place between Aug. 10 and 16 making six stops along the way, with up to 750,000 people coming out to see the orbiter and SCA. Workers towed Enterprise back from Dryden to the Palmdale plant on Oct. 30, where engineers removed computers and instruments to be refurbished and used in other orbiters then under construction.

Left: Pilot’s eye view of the launch tower looking through Enterprise’s forward windows. Middle: Enterprise rolling back into the VAB.

Right: Enterprise departing KSC atop the SCA.

Because Enterprise’s future was unclear, NASA returned it to Edwards Sep. 6, 1981, for long-term storage. On July 4, 1982, NASA used it as a backdrop for President Ronald W. Reagan to welcome home the STS-4 crew. The following year, NASA sent Enterprise on a European tour, departing Dryden on May 13, 1983, with stops in the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and France for the annual Paris Air Show. Enterprise made a stop in Ottawa, Canada, on its return trip to Dryden, arriving there June 13 and once again was placed in temporary storage.

Left: Enterprise as the backdrop for President Reagan welcoming home the STS-4 crew at Dryden in July 1982.

Right: Enterprise atop the SCA arriving at the Paris Air Show in May 1983.

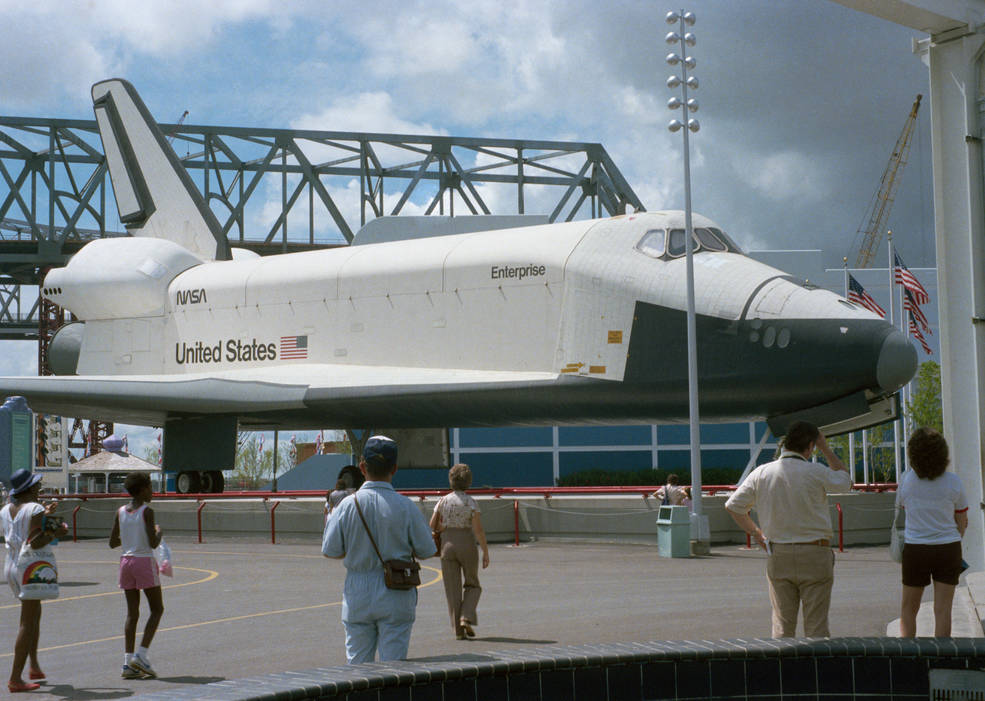

For its next public appearance, NASA ferried Enterprise to Mobile, Alabama, and from there transported it by barge to New Orleans, to be put on public display in the US pavilion of the World’s Fair between April and November 1984. After the public display, NASA ferried Enterprise to Vandenberg Air Force Base in California to conduct fit checks at the Space Launch Complex-6 (SLC-6), which NASA had planned to use for polar orbiting shuttle missions. NASA used Enterprise to conduct tests at SLC-6 similar to the 1979 tests at KSC’s Launch Complex 39. The tests at Vandenberg complete, NASA ferried Enterprise back to Dryden on May 24, 1985, but this time for only a very short-term storage.

Left: Enterprise on display at the World’s Fair in New Orleans in 1984.

Right: During static pad tests at SLC-6 at Vandenberg AFB in 1985.

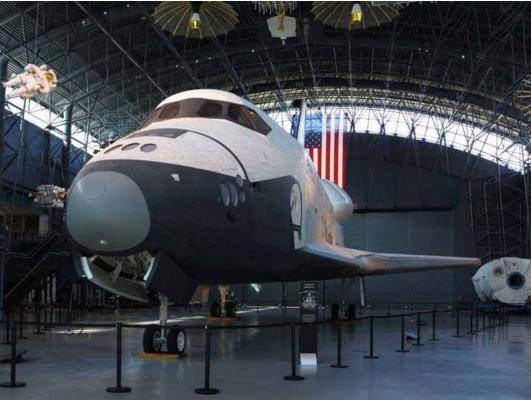

On Sep. 20, 1985, NASA ferried Enterprise to KSC and placed it on temporary public display near the VAB, next to the Saturn V already displayed there. On Oct. 30, Enterprise “saw” its sister ship Challenger fly into space for the final time on the STS-61A mission. After two months on display at KSC, NASA flew Enterprise to Dulles International Airport outside Washington, DC, arriving on Nov. 18, 1985. NASA officially retired Enterprise and transferred ownership to the Smithsonian Institution, which had plans to build a large aircraft annex at the airport. Enterprise was placed in storage in a hangar, awaiting the completion of its new home. That turned into an 18-year wait.

Left: Launch of STS-61A in October 1985, with Enterprise and Saturn V in the foreground.

Right: Enterprise on display in the Udvar-Hazy Center.

But even during that 18-year wait, NASA found practical use for the venerable Enterprise. In 1987, the Agency was concerned about how to handle an orbiter returning from space should it suffer a brake failure. To test the efficacy of an arresting barrier, workers slowly winched Enterprise into a landing barrier they had set up at Dulles to see if the vehicle suffered any damage. Later that same year, NASA used Enterprise to test various crew bailout procedures being developed in the wake of the Challenger accident. In 1990, experimenters used Enterprise’s cockpit windows to test mount an antenna for the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment, as no other orbiters were available. Periodically, engineers removed parts from Enterprise to test for materials durability, and also evaluated the structural integrity of the vehicle including its payload bay doors and found it to be in sound condition even after years in storage. In April 2003, in the wake of the Columbia accident, investigators borrowed Enterprise’s left landing gear door and part of the port wing for foam impact tests. The tests provided solid evidence that foam strike was the cause of the accident.

On Nov. 20, 2003, workers towed Enterprise from its hangar into the newly completed Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. Specialists restored the orbiter and the public was finally able to see it on Dec. 15. In 2011, NASA retired the Space Shuttle fleet and donated the vehicles to various museums around the country. The Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City acquired Enterprise, and on Apr. 27, 2012, workers removed the orbiter from its display at the Udvar-Hazy Center and placed it atop a SCA for the final time. After a short flight from Dulles and a flyaround of New York and several of its famous landmarks, Enterprise landed at John F. Kennedy International Airport. There to greet it was Leonard Nimoy who played Mr. Spock in the original Star Trek television series. Nimoy had been there in 1976 when Enterprise first rolled out in Palmdale. Workers lifted the orbiter from the SCA and placed it on a barge. It eventually arrived at the Intrepid Museum on June 3 and went on public display July 19. Enterprise suffered minor damage during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, but has been fully restored.

Enterprise in the Shuttle Pavilion at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City.

Credits: Intrepid Museum.

Read recollections about the Enterprise ALT flight in oral histories that Haise, Fullerton, and Engle conducted with the JSC History Office.

/quantum_physics_bose_einstein_condensate.jpg?w=1024)