The year 2003 was shaping up to be an ambitious one for NASA, with six space shuttle missions planned, five to continue construction of the ever-growing and permanently occupied International Space Station. The first flight of the year, STS-107 aboard NASA’s oldest orbiter Columbia, the first shuttle mission dedicated to microgravity research in nearly five years, would not travel to the space station but fly a 16-day solo mission. The seven-member crew would conduct many of the 80 planned U.S. and international experiments aboard a Spacehab Double Research Module in Columbia’s payload bay. The astronauts exceeded scientists’ expectations in terms of the science obtained during their 16 days in space. Tragically, the astronauts perished when Columbia broke apart during reentry on Feb. 1, 2003.

Left: STS-107 crew members David M. Brown, left, Rick D. Husband, Laurel

B. Clark, Kalpana Chawla, Michael P. Anderson, William C. “Willie” McCool,

and Ilan Ramon. Right: The STS-107 crew patch.

NASA first announced the STS-107 microgravity research mission, assigned to space shuttle Columbia, in March 1998, with a then-planned launch in May 2000, a date that began to slip almost immediately. In September 2000, NASA named the five-member science crew of Payload Commander Michael P. Anderson, Mission Specialists David M. Brown, Kalpana Chawla, and Laurel B. Clark, and Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon of the Israeli Space Agency, adding Commander Rick D. Husband and Pilot William C. “Willie” McCool three months later. Ramon’s participation grew out of a 1995 agreement between U.S. President Bill Clinton and Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres on space cooperation between the two nations. When assigned to the flight, the crew trained for an August 2001 launch, but various factors such as delays in Columbia’s refurbishment, technical issues affecting the space shuttle fleet, and competing priorities with a Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission and International Space Station assembly flights caused that date to slip to January 2003.

Left: STS-107 crew of Ilan Ramon, left, Laurel B. Clark, Michael P. Anderson,

Kalpana Chawla, David M. Brown, William C. “Willie” McCool, and Rick D.

Husband during the preflight press conference. Right: Husband, left,

McCool, Brown, Clark, Ramon, Anderson, and Chawla pose in front of

aT-38 Talon training aircraft at Ellington Field in Houston.

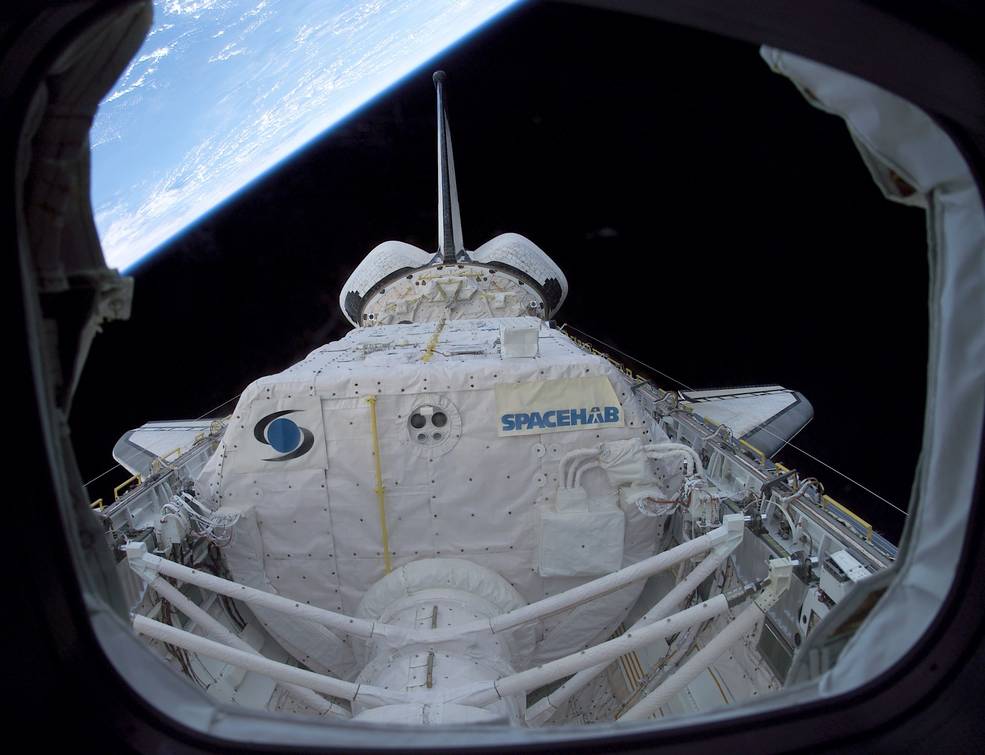

The STS-107 mission included a total of 80 experiments in a variety of research disciplines and carried out in different parts of the space shuttle. The astronauts worked directly with 32 payloads including 59 investigations in the Spacehab Research Double Module. These included nine commercial payloads involving 21 separate investigations, four payloads for the European Space Agency with 14 investigations, one investigation to mitigate risk for the International Space Station, and 18 payloads supporting 23 investigations for NASA in the fields of physical and biological sciences. Many of these experiments had application for future studies aboard the space station, prompting STS-107 Mission Scientist John B. Charles to refer to the mission’s research as doing “simulated space station science, although the science itself stands on its own right.” The Canadian Space Agency, the German Space Agency, the U.S. Air Force, and several universities also flew experiments in the Spacehab. Three experiments requiring exposure to open space flew attached to the top of the Spacehab module, while the Hitchhiker truss in the payload bay housed six experiments, including an Israeli investigation looking at Saharan dust distribution in the Mediterranean region using a multi-spectral camera.

Left: The STS-107 astronauts walk out of crew quarters at NASA’s Kennedy Space

Center in Florida to board the Astrovan for the ride to Launch Pad 39A.

Right: Liftoff of space shuttle Columbia on the STS-107 mission.

Space shuttle Columbia began its 28th mission with a spectacular liftoff from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, at 10:39 am EST on Jan. 16, 2003. The launch appeared to go well and after eight and a half minutes, Columbia reached its planned orbit to begin the 16-day microgravity research mission. Beginning on their very first day in space, the seven-member crew split into two teams – Husband, Chawla, Clark, and Ramon made up the Red Team while McCool, Anderson, and Brown made up the Blue Team. For the duration of the mission, the teams worked opposite shifts, allowing for 16 days of continuous research operations. Brown busied himself with opening Columbia’s payload bay doors, while Anderson, Clark, and Ramon reconfigured the orbiter from a rocket to a spacecraft to support research, including activating the Spacehab research module. The Blue Team took the first sleep shift while the Red Team began to activate some of the experiments. For the next 15 days, Columbia’s crew worked tirelessly to complete the experiments, overcoming technical issues. Scientists on the ground were overjoyed at their performance and amazed at the greater than expected science return from the mission.

Left: STS-107 Commander Rick D. Husband on Columbia’s flight deck.

Right: STS-107 Pilot William C. “Willie” McCool on Columbia’s

aft flight deck.

Left: View into Columbia’s payload from the aft flight deck showing the Spacehab Double Research

Module. Middle: A view from the transfer tunnel into the Spacehab module where Payload Commander

Michael P. Anderson conducts experiments. Right: Anderson at work in the Spacehab module.

During routine analysis of launch films, engineers noted that at about 82 seconds into the flight, a piece of foam insulation released from the Shuttle’s External Tank (ET) appeared to strike Columbia’s left wing. On Jan. 23, the mission’s eighth day, Flight Director J. Steve Stich from Mission Control notified Husband and McCool of the foam strike via an email, including a video clip of the impact, but assured them that because the phenomenon had occurred on previous missions, it caused no concern for damage to the vehicle or for reentry. Husband informed the rest of the crew. However, engineers on the ground continued to assess the impact of the foam strike, requesting high-resolution imaging of the affected area to complete a more thorough analysis, but ultimately managers turned down the request. On Jan. 27, the STS-107 crew chatted via radio with the three Expedition 6 crew members aboard the International Space Station, in the third month of their planned five month mission.

Left: STS-107 astronauts Laurel B. Clark, left, Rick D. Husband, and Kalpana Chawla in the sleep

quarters in Columbia’s middeck. Middle: Astronauts Michael P. Anderson, left, Chawla, Ilan Ramon,

and David M. Brown in the Spacehab module. Right: William C. “Willie” McCool

works on a blood sample.

Left: STS-107 astronauts Kalpana Chawla, left, and Rick D. Husband in the Spacehab research module.

Middle left: David M. Brown works with a camera in the Spacehab module. Middle right: Laurel B.

Clark, wearing purple gloves, works on an experiment in the Spacehab module. Right: View from

Columbia of Israel and the northern Sinai peninsula.

On Jan. 28, Columbia’s crew members paid tribute to their fellow astronauts lost in the Challenger accident 17 years earlier and in the Apollo 1 launch pad fire on Jan. 27, 1967. Husband said, “It is today that we remember and honor the crews of Apollo 1 and Challenger. They made the ultimate sacrifice: giving their lives in service to their country and for all mankind. Their dedication and devotion to the exploration of space was an inspiration to each of us, and still motivates people around the world to achieve great things in service to others.”

Left: STS-107 astronaut Kalpana Chawla works on an experiment in the Spacehab research module.

Middle: STS-107 Commander Rick D. Husband, left, with Israeli Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon

on Columbia’s flight deck. Right: In-flight STS-107 crew photo, with Red Team members

Kalpana Chawla, left, Rick D. Husband, Laurel B. Clark,and Ilan Ramon at bottom, and

Blue Team members David M. Brown, left, William C. “Willie” McCool, and

Michael P. Anderson, at top.

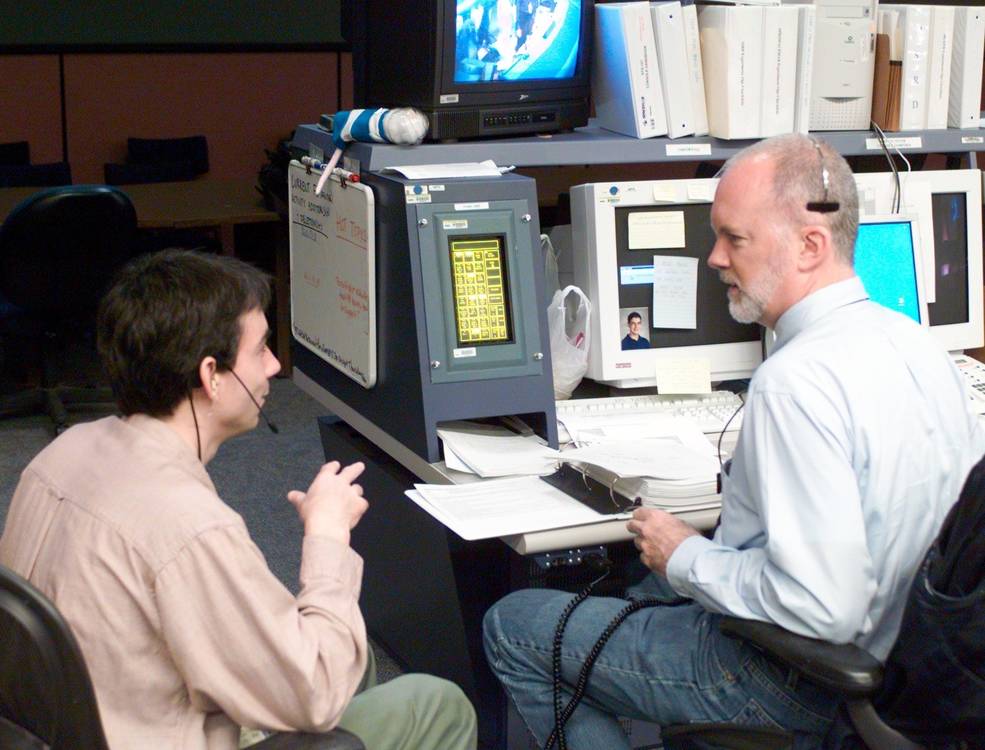

Left: In the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, STS-107 Mission

Scientist John B. Charles confers with specialist Andy Self on the status of the research

aboard Columbia on Jan. 30, 2003. Middle: The Mission Control Center at the moment of

loss of contact with Columbia on Feb. 1, 2003. Right: Flight Director Leroy E. Cain,

right, and capsule communicator NASA astronaut Charles O. “Scorch” Hobaugh, center,

in the moment after Cain’s order to “Lock the doors” following loss of

space shuttle Columbia and her crew.

The astronauts completed the last science sessions on Jan. 31 while Husband and McCool used a simulator to practice the entry and landing procedures and tested Columbia’s systems required for the return to Earth. The next morning, they closed the hatches to the Spacehab module, then closed the payload bay doors, with the entry team led by Flight Director Leroy E. Cain monitoring their activities from Mission Control. The astronauts donned their orange launch and entry suits and took their seats, with Husband, McCool, Chawla, and Clark on the flight deck and Brown, Anderson, and Ramon in the middeck. Husband and McCool oriented Columbia with its Orbital Maneuvering System engines pointing in the direction of flight, and after receiving the go for the deorbit burn from capsule communicator NASA astronaut Charles O. “Scorch” Hobaugh, fired the engines for two minutes and 38 seconds over the Indian Ocean. They reoriented Columbia with its nose facing forward and angled up at 40 degrees to face the heat of reentry, encountering the Earth’s atmosphere at 400,000 feet. To help slow the vehicle down, it flew a series of maneuvers to bleed off energy. Fifteen minutes after entry interface, flying over Texas at an altitude of 207,000 feet and 16 minutes from landing at KSC, Mission Control lost contact with Columbia and her crew.

Sixteen Minutes from Home

A Personal Remembrance

As far as Saturday mornings go, this one starts off pretty ordinary. My seven-year-old daughter Alex and I are at home; my wife Susan is at church for a meeting. Alex may disagree about ordinary, since instead of her usual cartoons or Disney videos, I have the family room TV tuned to the NASA channel to watch the space shuttle land in Florida this morning. Along with the launches that are far more spectacular, I make it a habit to watch these events live – as on this day, friends and colleagues are sometimes on board.

As we settle on the couch, the aroma of bacon and French toast lingers, evidence of the bribe to keep Alex’s complaining to a minimum. But I still get a few “Why do we have to watch this, it’s so boring!” and “Is it over yet?” sprinkled with the usual chatter of a seven-year-old as she reads her book. A welcome distraction from the NASA public affairs official announcing each passing milestone of the reentry. The newspaper rustles as I fold it up, I’ve finished reading the funnies, and I turn my attention to the TV as the time draws near. Touchdown is 16 minutes away.

Columbia’s crew was returning that morning from a 16-day science mission that had gone exceedingly well. In Mission Control, the scientists beamed at the results of the experiments, excited in their nerdy scientist way. The astronauts, confident as always, cavorting in weightlessness, making it all seem so easy. They thanked all the people who helped them prepare for the flight and looked forward to being home and sharing their adventure with everyone. Four days ago, they honored their fallen comrades, fellow astronauts lost in the Apollo fire and the Challenger accident, with a moment of silence.

Sure, there was talk of something that hit the wing during liftoff 16 days ago, but that was nothing to worry about, right? That happens all the time, and it always turns out ok, right? If it was serious, someone would be doing something about it. Right?? Of course! And besides, just a few days ago, Mission Control assured the astronauts there was “absolutely no concern for reentry.”

“Fourteen minutes to touchdown for Columbia,” says the public affairs announcer, breaking the silence. “Flight controllers continuing to standby to regain communications with the spacecraft.”

“Columbia, Houston. Comm check,” the capcom, or capsule communicator, calls to the crew, awaiting a response to the communications check. Silence. He tries again. Silence.

The first wispy tendrils of fear begin to tighten my insides. Something doesn’t feel right. They’ve been silent for more than two minutes. The usual communications blackout ended a while back. I now long for the usual boring technical chatter.

“Twelve and a half minutes to touchdown,” says the public affairs announcer.

“Columbia, Houston. Comm check.

“Columbia, Houston. Comm check.”

“Flight controllers are standing by for Columbia to move within range of the tracking station in Florida,” says public affairs. “And also waiting for tracking data from Florida.

“Ten and a half minutes to anticipated touchdown for Columbia.” The crescendo of fear is joined by confusion and a desperate need to know what’s happening, as more calls go unanswered.

“Eight minutes on the touchdown clock for Columbia.” Still no response from the crew.

“Six minutes to touchdown.” Ten minutes without a response, and more worrisome, radars in Florida see nothing where the shuttle should be. Mission Control declares a “contingency,” NASA-speak for “something’s gone seriously wrong.” They lock the doors, preserve all the data for the investigation to come. My insides are in a full-blown churn.

The countdown clock to touchdown reaches zero. They should have landed by now, announcing their arrival by the familiar double sonic boom. Searching the skies, searching in vain. Willing them to appear out of thin air into the empty silent Florida skies. But they’re late. They can’t be late. This is not right. I think of the families left waiting, wondering.

I turn to Alex, her chatter stops in mid-sentence. “Alex, this is very serious, we need to pay attention,” I say. “Something really bad has happened. I think my friends are in trouble, they may have died. I need to listen, OK?” She nods, her eyes big as saucers.

Frustrated with the lack of information on NASA TV, I switch to CNN and am inundated. My breath stops when they show the video from Dallas – one streak spreading into many, Columbia breaking up 200,000 feet over Texas. My brain toys with the idea that maybe they bailed out, but reality sinks in, I know they were too high for that. The grip of fear releases, unleashing a wave of tears, mercifully blurring the endless replays of that awful video.

I need to reach out, to call someone, to share the grief. Susan doesn’t answer. Of course, in a meeting, phone turned off. I try again anyway. Voice mail. I call coworkers. We share our feelings, something we don’t normally do. We ponder what to do, realize there is nothing. One I reach at the airport on his way to Japan – he hadn’t heard so I break the news to him. Then I feel bad about that. He’ll spend the next 14 hours in an airplane with no hope of updates. The rest of the day is a fog of swirling emotions, as I sit glued to the TV for news, unable to turn away.

Alex later told me that was the first time she’d ever seen me cry.

Columbia’s Aftermath and Legacy

Left: Flags fly at half-staff at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston following the Columbia

tragedy. Middle: President George W. Bush speaks at the memorial at JSC for the seven astronauts

lost in the tragedy. Right: NASA Administrator Sean C. O’Keefe speaks at the JSC Columbia memorial.

In the Mission Control Center, after realizing that tragedy had struck Columbia, Cain ordered the doors locked and directed his controllers to save all data for the coming investigation. Within 90 minutes after the accident, NASA Administrator Sean C. O’Keefe convened the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB), appointing retired Admiral Harold W. Gehman as its chair, to determine the causes of the tragedy. Five hours after the tragedy, President George W. Bush addressed a shocked nation, “My fellow Americans, this day has brought terrible news, and great sadness to our country. … The Columbia is lost; there are no survivors.” By that time, authorities in Texas and Louisiana had begun the arduous task of recovering the remains of the astronauts and the debris from Columbia, a process that took more than three months and resulted in the recovery of about 38% of Columbia by weight. Three days after the tragedy, President Bush and First Lady Laura Bush led a memorial service at JSC for the seven lost astronauts.

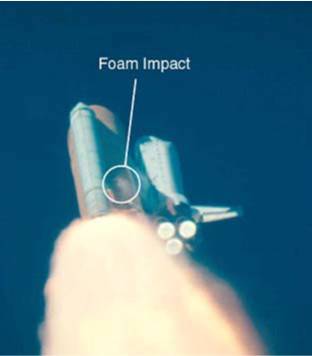

Left: View of the launch of Columbia on the STS-107 mission, showing the location of the foam

shedding and the point of impact on the orbiter’s left wing. Middle: Still from a video of the

STS-107 launch showing the moment of the foam impact on the wing leading edge.

Right: Photograph of a sample of space shuttle wing leading edge following an

experimental foam strike at the Southwest Research Institute.

By May 2003, following a series of hearings, examination of the debris, and experimental foam impact tests on reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) material like the orbiter’s wing leading edge conducted at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, the CAIB released their working scenario for the accident, confirmed in the final report released on Aug. 26, 2003. The immediate cause of the accident began approximately 82 seconds after Columbia’s launch on Jan. 16, as demonstrated in the post-launch photographic analysis. The foam from the ET’s left bipod ramp area impacted Columbia in the vicinity of the lower left wing RCC panels 5-9. While on orbit for 16 days, neither the Columbia crew nor controllers on the ground had any indication of damage based on orbiter telemetry, crew downlinked video, still photography, or crew reports. When the vehicle began reentry this damaged section of the wing was subjected to extreme entry heating over a long period of time. The destruction of the wing from overheating caused the breakup and crash of Columbia. The CAIB report also criticized NASA’s organizational and safety culture, finding similar faults that led to the 1986 Challenger accident. Among the criticisms, the report stated that NASA had become complacent to the loss of foam from the ET, since none had led to significant issues other than postflight maintenance. The lessons learned from the Columbia accident are summarized in this case study. In 2008, NASA released the “Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report” that summarized the impact of the accident on the astronauts. Despite the loss of Columbia, some of the science conducted during its final 16-day mission was recovered. For those experiments that mostly downlinked their data, scientists acquired between 50% and 90% of their results. For those experiments that relied on returned samples, those results could not be salvaged, with the one remarkable exception of some microscopic worms called C. elegans that had survived the extremes of the reentry and crash.

Left: NASA Administrator Sean C. O’Keefe accepts a copy of the Columbia Accident Investigation

Board’s (CAIB) report from its chair, Admiral Harold W. Gehman. Middle: The cover of the CAIB

Report. Right: The cover of the “Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report.”

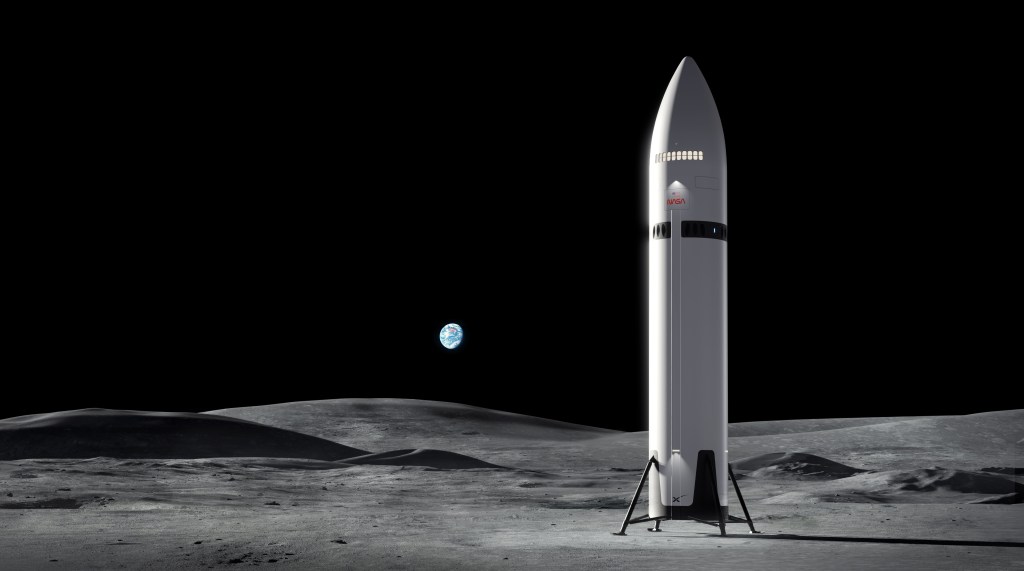

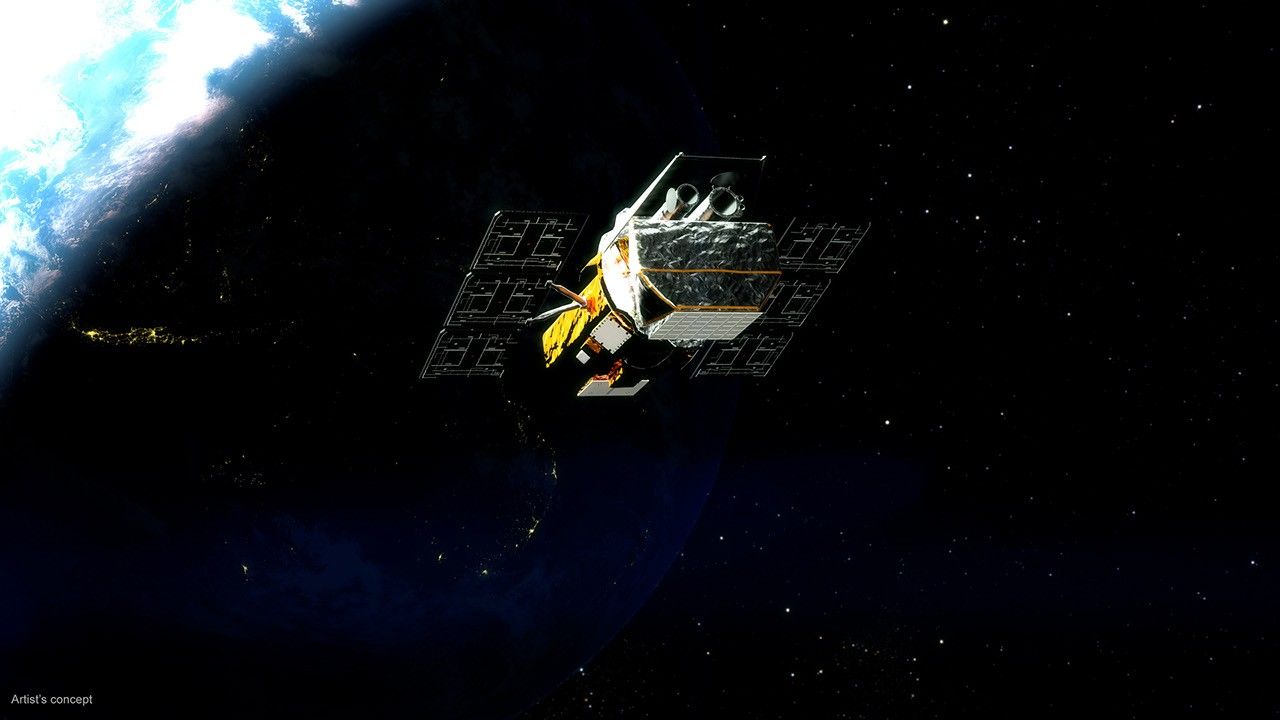

The Columbia tragedy led to the grounding of the space shuttle fleet as NASA implemented the recommendations from the CAIB, especially to gain a better understanding and control of foam shedding from the ET. The fleet remained grounded for more than 29 months, until the STS-114 return to flight mission of Discovery in July 2005. By then, President Bush had announced his Vision for Space Exploration in January 2004 that called for the retirement of the shuttle after completing assembly of the space station. The shuttle flew its last mission, the STS-135 flight of Atlantis in July 2011. For future human space flights, NASA developed the Crew Exploration Vehicle, now called Orion, for deep space exploration missions. After its first uncrewed test flight in December 2014, Orion made its first uncrewed flight to the Moon in November-December 2022, launching aboard the Space Launch System as the Artemis 1 mission. Future Artemis missions will see Orion spacecraft take astronauts to the Moon, leading to landing the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon. For crew missions to and from the International Space Station, after the shuttle’s retirement NASA relied on Russian Soyuz vehicles until the beginning of commercial crew launches began in May 2020 using the SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft.

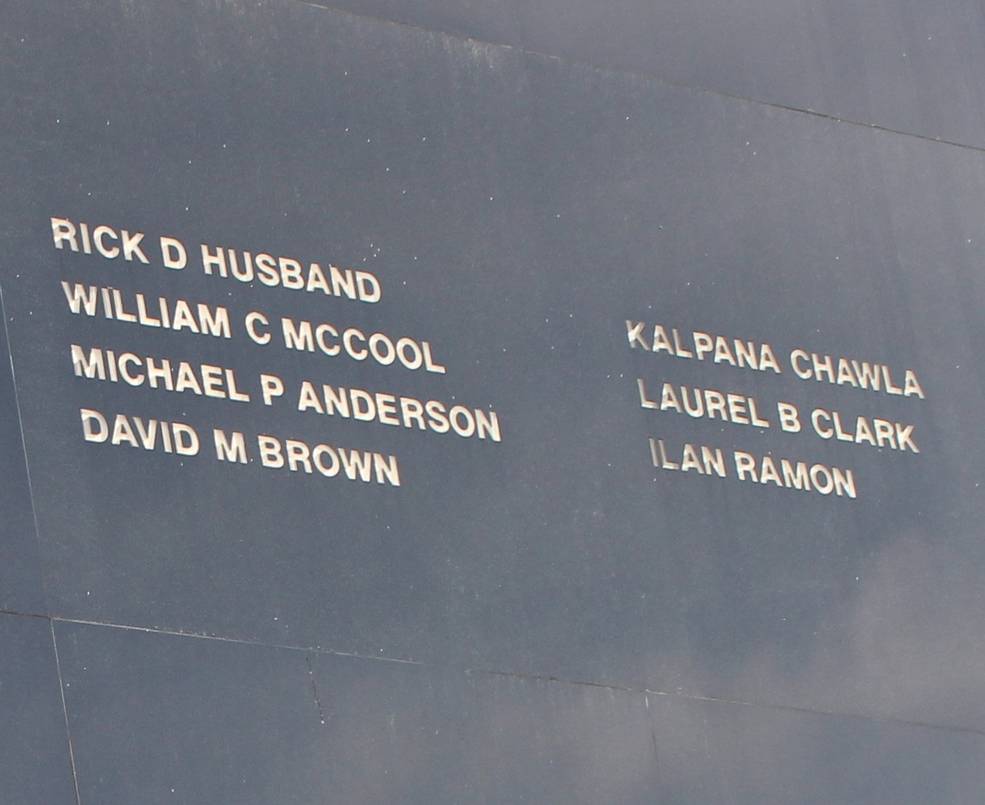

Left: A makeshift memorial outside NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston pays tribute to the

seven STS-107 astronauts. Middle: The names of the seven astronauts lost in the Columbia tragedy,

engraved on the Space Mirror Memorial at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Visitor Complex.

Right: A section of the fuselage recovered from space shuttle Columbia on display at

the “Forever Remembered” exhibit at NASA’s KSC Visitor Complex.

“Forever Remembered,” a collaborative exhibit between NASA and the families of the astronauts lost in the Challenger and Columbia tragedies, opened at the KSC Visitor Complex in 2015. The memorial honors the crews, pays tribute to the spacecraft, and emphasizes the importance of learning from the past. Displays include personal belongings from each of the crew members and recovered pieces from both Challenger and Columbia. Also at the KSC Visitor Complex, the names of the seven astronauts lost in the Columbia tragedy are engraved on the Space Mirror Memorial. At JSC, NASA planted seven trees in the Astronaut Memorial Grove to honor the seven Columbia crew members. To honor the astronauts lost in the Columbia accident, as well as those lost in the Apollo 1 fire and the Challenger accident, every year at the end of January, NASA holds a Day of Remembrance. The day allows NASA employees to reflect not only on the lives lost but also on the circumstances that led to the accidents and the resulting changes to NASA’s operations and safety culture. It is also a time to ensure that everyone does their utmost to prevent future tragedies from happening through a culture of heightened safety and excellence, especially important as NASA embarks on new programs in collaboration with international and commercial partners and plans to return humans to the Moon as part of the Artemis program.

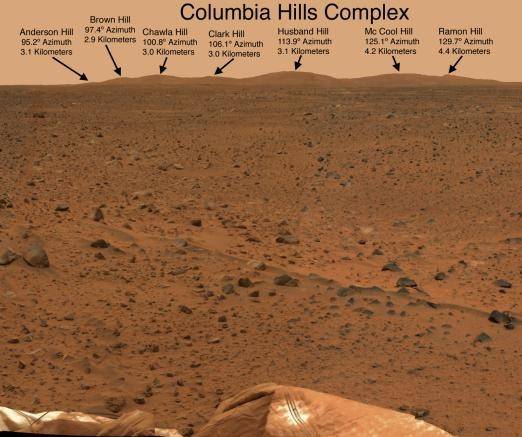

Left: A wreath in honor of Columbia’s crew at the Astronaut Memorial Grove at NASA’s

Johnson Space Center in Houston, during the 2009 Day of Remembrance event.

Right: The Columbia Hills on Mars taken by the Mars Exploration Rover

Spirit, whose landing site NASA designated as the

Columbia Memorial Station.

Honors to the seven Columbia astronauts extend beyond Earth as well. In August 2003, seven asteroids discovered two years earlier were named after the seven astronauts: 51823 Rickhusband, 51824 Mikeanderson, 51825 Davidbrown, 51826 Kalpanachawla, 51827 Laurelclark, 51828 Ilanramon, and 51829 Williemccool. The Mars Exploration Rover Spirit that landed on the Red Planet in January 2004 included a memorial plaque to the Columbia crew and NASA designated its landing site as the Columbia Memorial Station. Scientists dubbed a complex of seven hills east of Spirit’s landing site as the Columbia Hills, with each hill named for a member of the crew. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union approved naming seven craters in the Apollo basin on the Moon after the Columbia astronauts.