The story of the Cassini mission begins long before the NASA spacecraft first beamed back images of Saturn’s rings or when the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe touched down on Titan, or even its launch in the early morning of October 15, 1997, atop a Titan IV-Centaur rocket.

It’s a tale penned by the more than 5,000 people who have made the mission a success – those with vested interest, watching intently on Friday as Cassini dives into Saturn’s atmosphere for its end of mission finale.

Part of the prologue to Cassini’s story began with a group of engineers at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, who were responsible for launching Cassini and getting it beyond Earth’s orbit as it began the more than 2.1-billion mile trek to Saturn.

Here, we join the narrative of five members of NASA Glenn’s 65-person launch team, dedicated to making the Cassini mission, like the ones before it, a success.

The Agency’s Propulsion Powerhouse

This is part one of a five-part series detailing personal accounts of NASA Glenn’s Cassini Mission launch team.

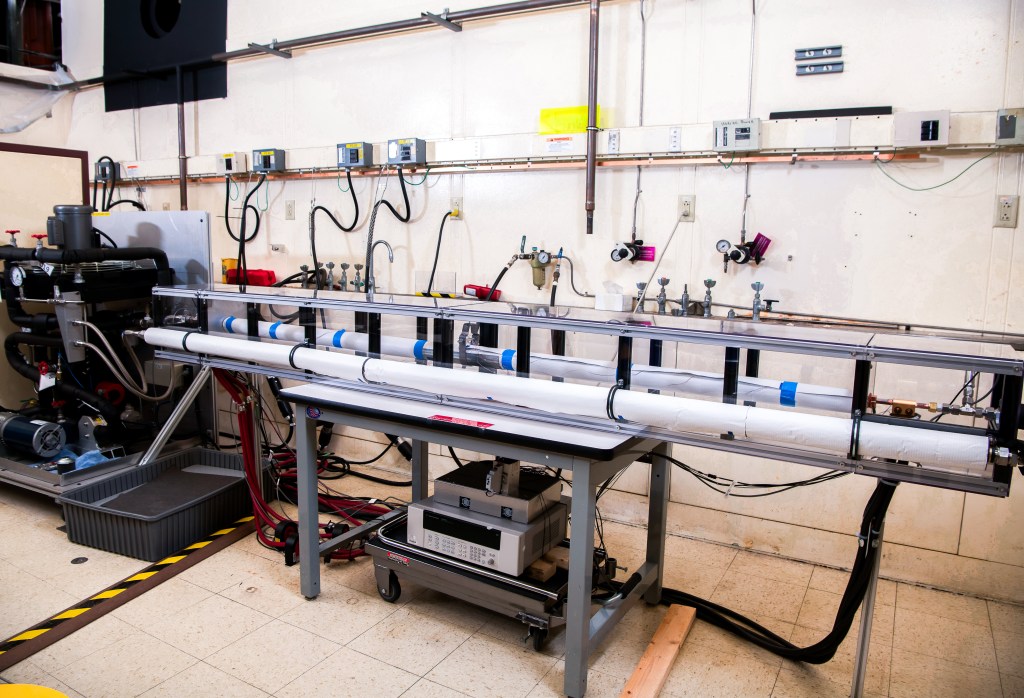

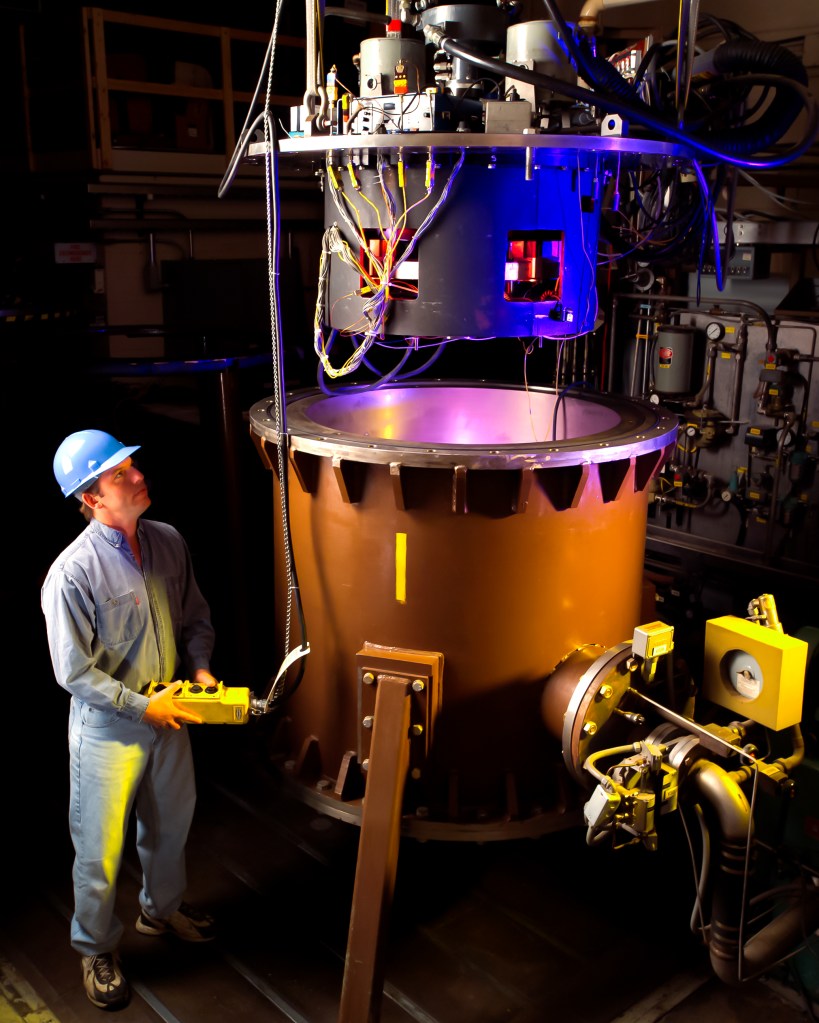

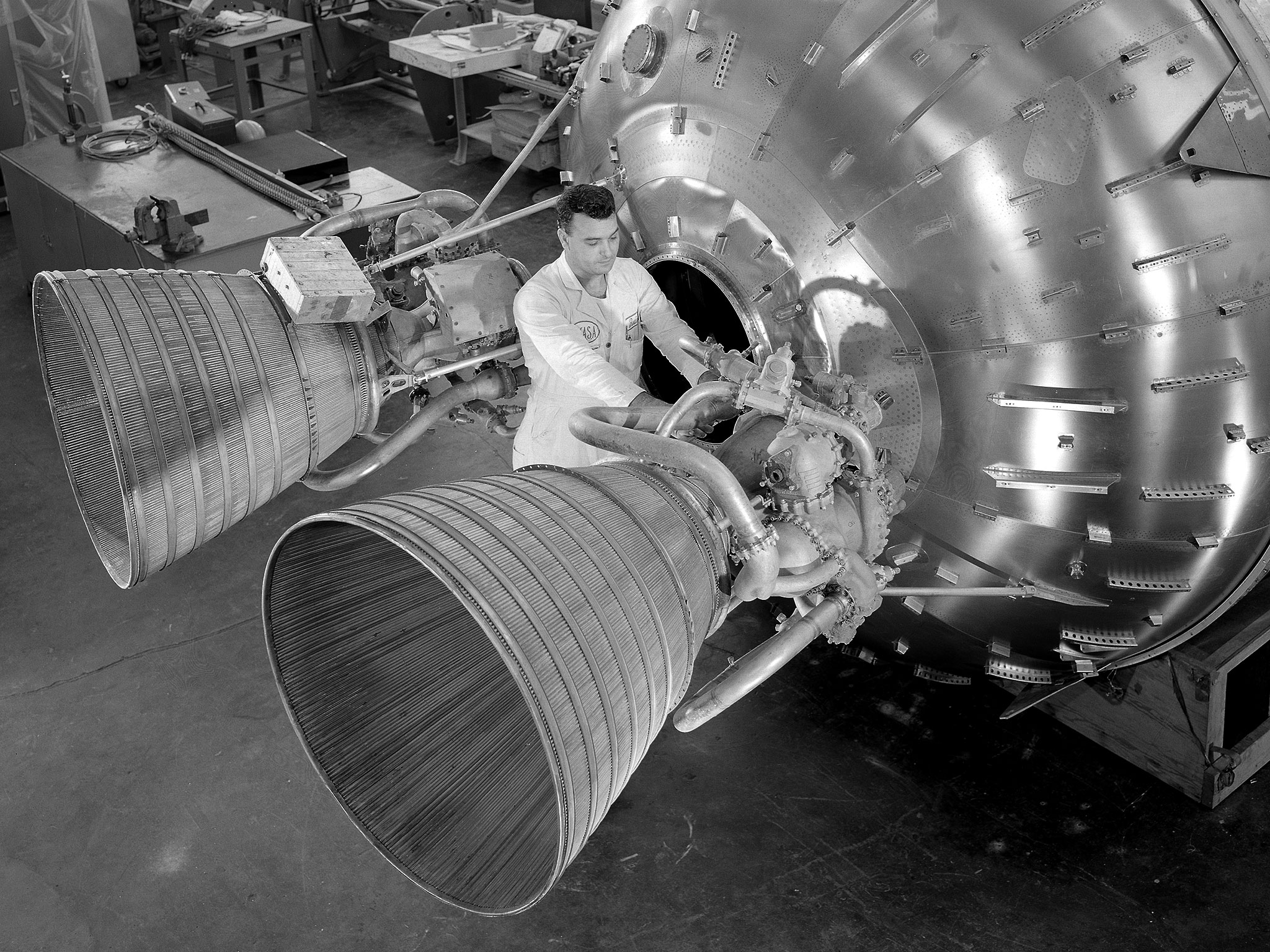

Nearly a half century before Cassini sat above Space Launch Complex 40 at Cape Canaveral, NASA Glenn, then NASA Lewis, was tasked, as the agency’s premier power and propulsion research center, with the development of liquid hydrogen as rocket fuel.

“We originally started to develop hydrogen fuel for aircraft,” said Scott Graham, who began his career at NASA Glenn in the early 1980s working on rocket engines. “That soon evolved into hydrogen fuel for rocket engines which had never been done before. We were pioneers into research involving not just hydrogen, but cryogenic liquid hydrogen fuels. It was, and still is, very difficult to work with, but Glenn was key in harnessing the most energetic rocket propellant that one can have.”

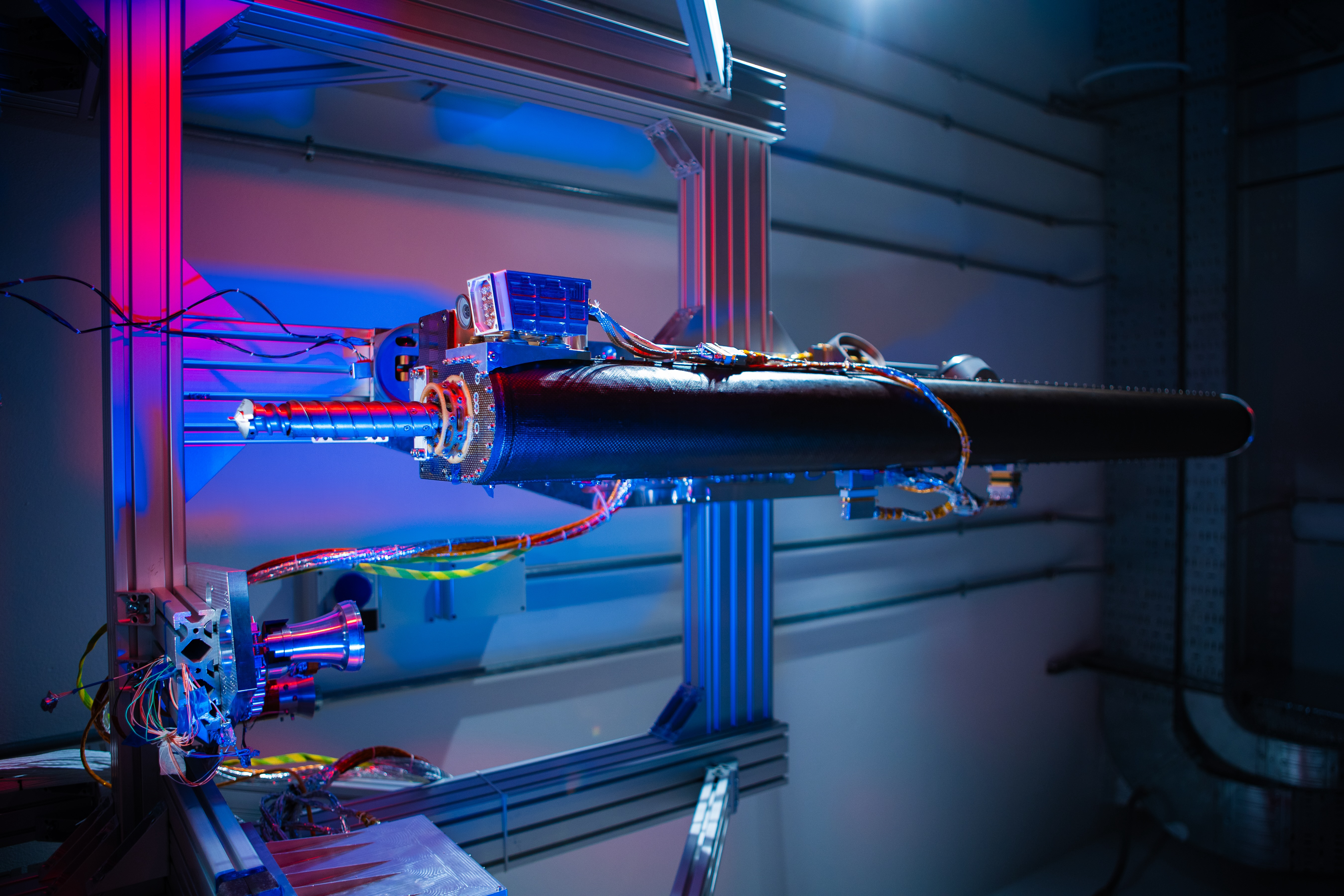

Eventually, NASA Glenn’s pioneering work set the stage for liquid hydrogen to become the go-to propellant for NASA’s large expendable launch vehicles program, in particular, the RL-10 rocket engine and the Centaur high-energy upper stage.

“Glenn began developing liquid hydrogen propellants very early, and if you look at every spacefaring nation in the world today, nearly all have upper stages that use liquid hydrogen as fuel,” said Joe Nieberding, who began his NASA career working on Centaur in 1966. “All of those systems – from Apollo up through shuttle – are based off the work Glenn did back in the late 1950s and early 60s.”

The Centaur upper stage would go on to become the agency’s workhorse over the next 40 years, launching 80 missions into the heavens under NASA Glenn’s leadership. These missions included 42 communication satellites, six low Earth orbit observatories, eight test flights, and 24 lunar and interplanetary probes, including Surveyor, Mariner, Pioneer, Voyager, Viking and Cassini.

“You could say that NASA Glenn’s work in liquid hydrogen propellants, and especially Centaur, enabled NASA to visit basically every planet in our solar system within a span of 15 to 20 years,” said Nieberding. “We accomplished a magnificent amount of science with this one upper stage.”

The Cassini launch, however, holds a special place in NASA Glenn lore not only because it marked one of the most complex missions to plan using a new version of Centaur, but it also became the capstone to NASA Glenn’s expendable launch vehicles program.