Say cheese again, Moon. We’re coming in for another close-up.

For the second time in less than a year, a NASA technology designed to collect data on the interaction between a Moon lander’s rocket plume and the lunar surface is set to make the long journey to Earth’s nearest celestial neighbor for the benefit of humanity.

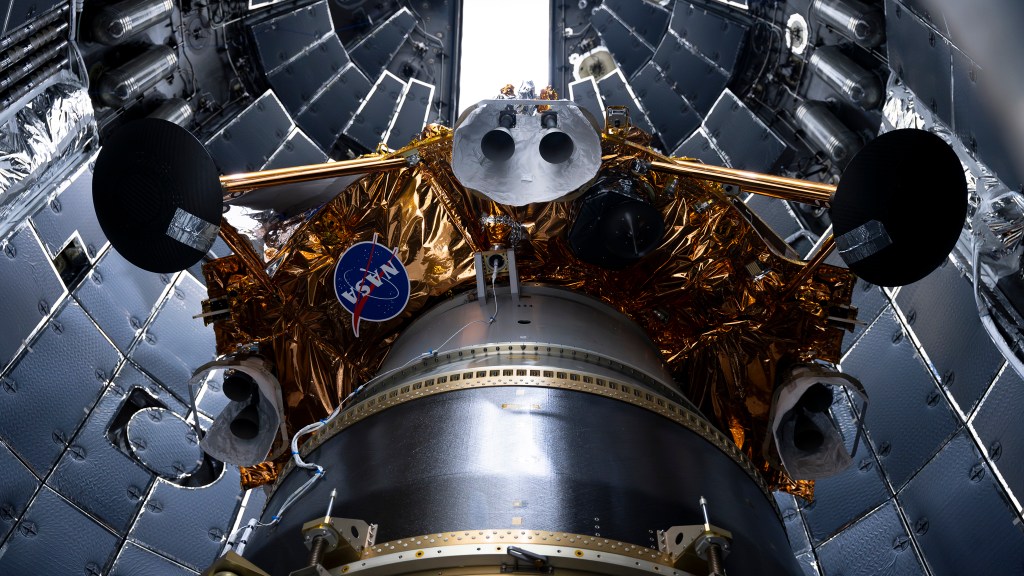

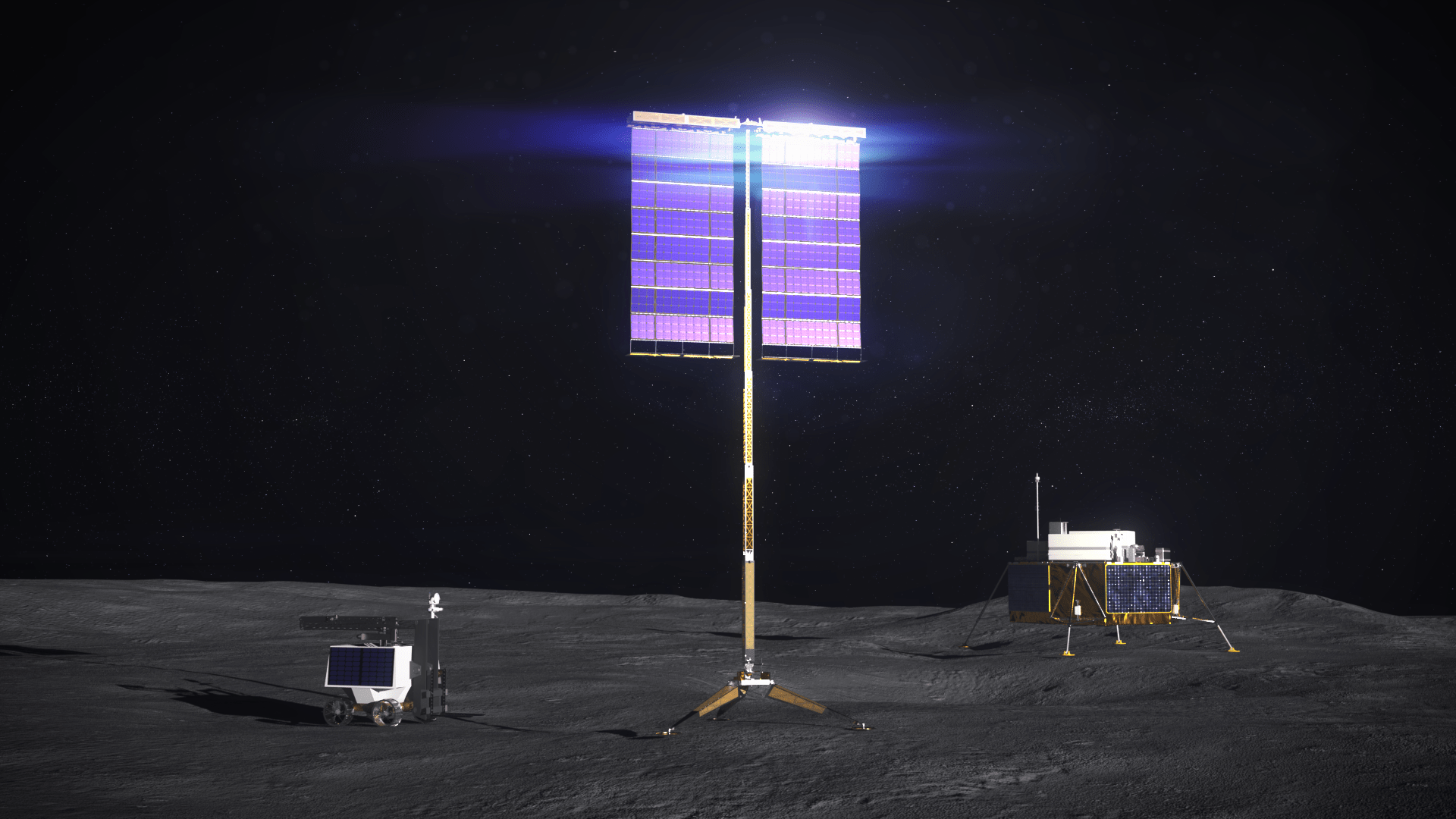

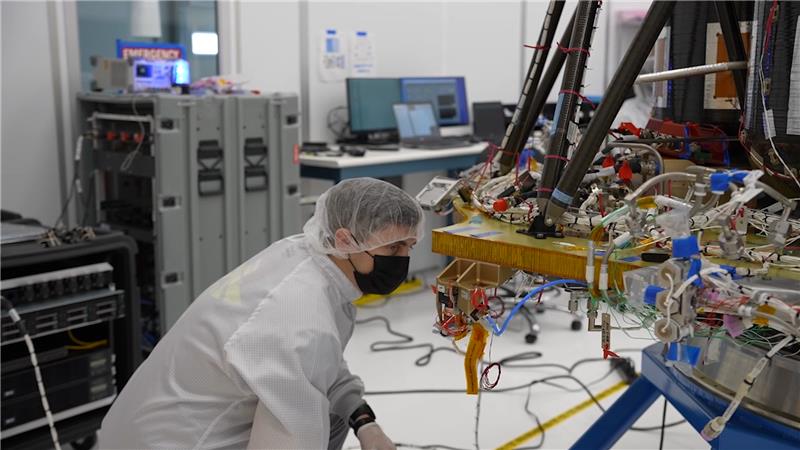

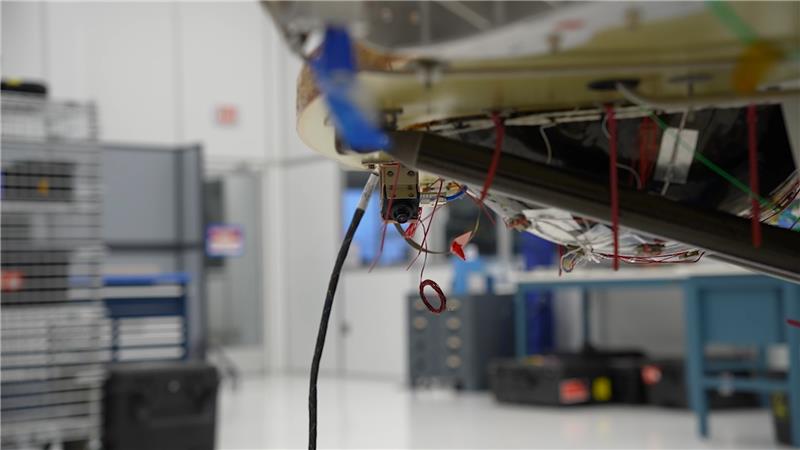

Developed at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, Stereo Cameras for Lunar Plume-Surface Studies (SCALPSS) is an array of cameras placed around the base of a lunar lander to collect imagery during and after descent and touchdown. Using a technique called stereo photogrammetry, researchers at Langley will use the overlapping images from the version of SCALPSS on Firefly’s Blue Ghost — SCALPSS 1.1 — to produce a 3D view of the surface. An earlier version, SCALPSS 1.0, was on Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus spacecraft that landed on the Moon last February. Due to mission contingencies that arose during the landing, SCALPSS 1.0 was unable to collect imagery of the plume-surface interaction. The team was, however, able to operate the payload in transit and on the lunar surface following landing, which gives them confidence in the hardware for 1.1.

The SCALPSS 1.1 payload has two additional cameras — six total, compared to the four on SCALPSS 1.0 — and will begin taking images at a higher altitude, prior to the expected onset of plume-surface interaction, to provide a more accurate before-and-after comparison.

These images of the Moon’s surface won’t just be a technological novelty. As trips to the Moon increase and the number of payloads touching down in proximity to one another grows, scientists and engineers need to be able to accurately predict the effects of landings.

How much will the surface change? As a lander comes down, what happens to the lunar soil, or regolith, it ejects? With limited data collected during descent and landing to date, SCALPSS will be the first dedicated instrument to measure the effects of plume-surface interaction on the Moon in real time and help to answer these questions.

“If we’re placing things – landers, habitats, etc. – near each other, we could be sand blasting what’s next to us, so that’s going to drive requirements on protecting those other assets on the surface, which could add mass, and that mass ripples through the architecture,” said Michelle Munk, principal investigator for SCALPSS and acting chief architect for NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “It’s all part of an integrated engineering problem.”

Under the Artemis campaign, the agency’s current lunar exploration approach, NASA is collaborating with commercial and international partners to establish the first long-term presence on the Moon. On this CLPS (Commercial Lunar Payload Services) initiative delivery carrying over 200 pounds of NASA science experiments and technology demonstrations, SCALPSS 1.1 will begin capturing imagery from before the time the lander’s plume begins interacting with the surface until after the landing is complete.

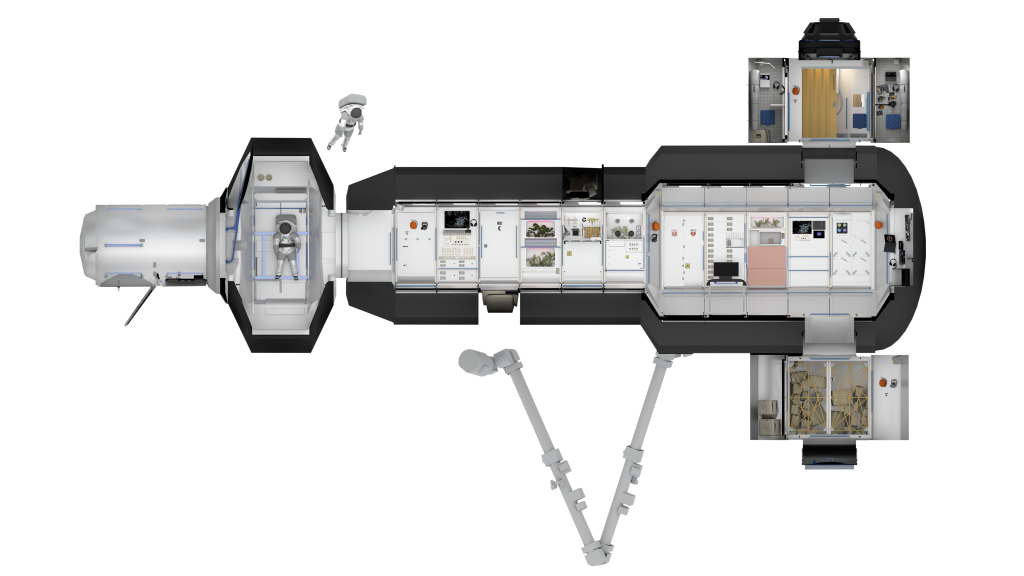

The final images will be gathered on a small onboard data storage unit before being sent to the lander for downlink back to Earth. The team will likely need at least a couple of months to

process the images, verify the data, and generate the 3D digital elevation maps of the surface. The expected lander-induced erosion they reveal probably won’t be very deep — not this time, anyway.

“Even if you look at the old Apollo images — and the Apollo crewed landers were larger than these new robotic landers — you have to look really closely to see where the erosion took place,” said Rob Maddock, SCALPSS project manager at Langley. “We’re anticipating something on the order of centimeters deep — maybe an inch. It really depends on the landing site and how deep the regolith is and where the bedrock is.”

But this is a chance for researchers to see how well SCALPSS will work as the U.S. advances human landing systems as part of NASA’s plans to explore more of the lunar surface.

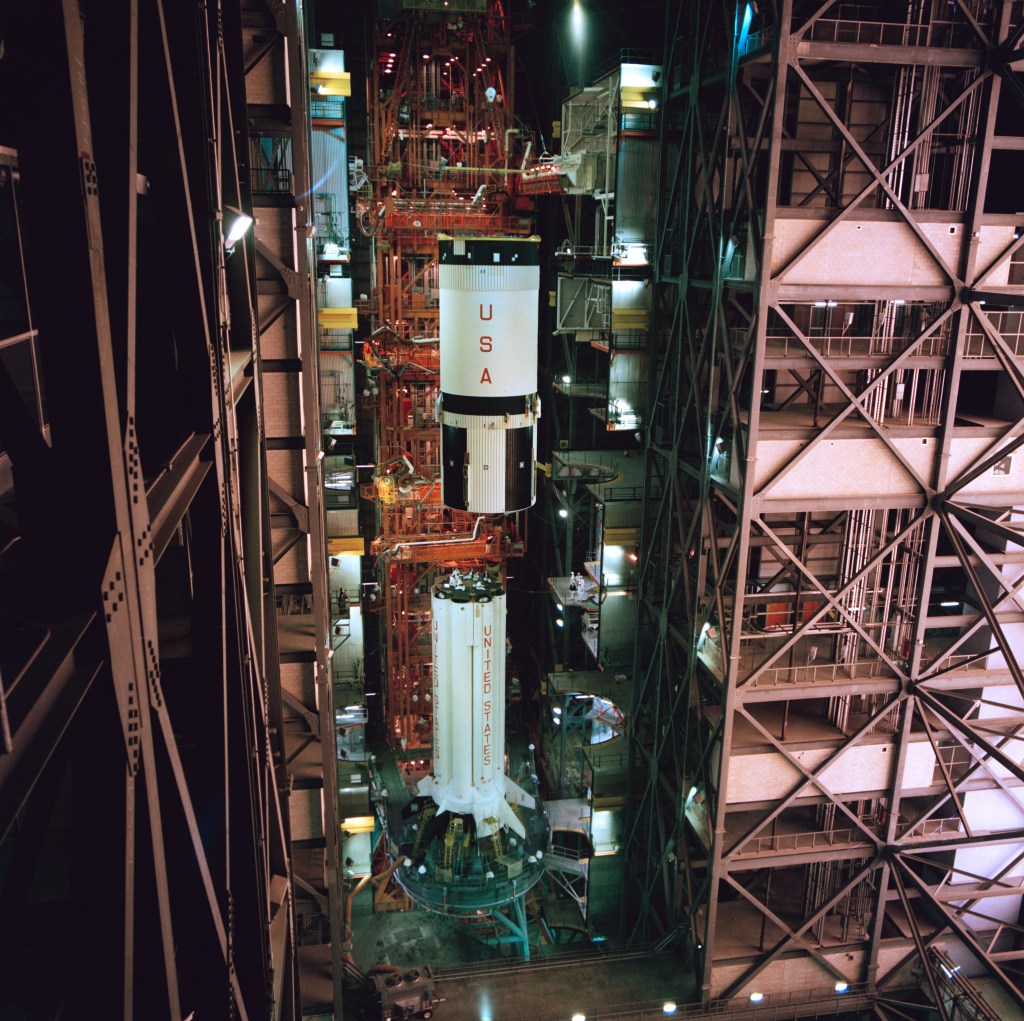

“Those are going to be much larger than even Apollo. Those are large engines, and they could conceivably dig some good-sized holes,” said Maddock. “So that’s what we’re doing. We’re collecting data we can use to validate the models that are predicting what will happen.”

The SCALPSS 1.1 project is funded by the Space Technology Mission Directorate’s Game Changing Development Program.

NASA is working with several American companies to deliver science and technology to the lunar surface under the CLPS initiative. Through this opportunity, various companies from a select group of vendors bid on delivering payloads for NASA including everything from payload integration and operations, to launching from Earth and landing on the surface of the Moon.