If you’ve read any of these interviews you probably know that we go back to your beginnings and ask where you were born, where you grew up, about your family at that time, any siblings, what your parents did for a living, and if there might have been something, even at an early age, that focused your mind toward the work that you eventually pursued academically and now in your career?

Well, I was a problem child from the very beginning!

Oh! What a great opening line! “It was a dark and stormy night!” (laughs). I love that! That is a grabber, right there. Someone’s going to read that line and say “I’m going to read every word of this interview!” (laughs)

I caused my mother pain by being born at 2:55 am on a Friday in February! I was born in Charleston, South Carolina. My parents moved there in the 1940s, as immigrants from Europe, as Jews who survived World War II. They were in a displaced persons camp in Austria for a few years before deciding to come to the U.S. They moved to Charleston, South Carolina because they had some distant family relations there. I’m the youngest of four children. One of the things that drove me to be interested in science, there were a few things, is that my mom was pretty good about trying to get me interested in the world. I remember being four years old and she gave me kids’ picture books about things, and I was really interested in this one about the planets. There were other ones too, about birds and dinosaurs and all that, but space caught my attention. I remember knowing all the planets in the correct order when I was being dropped off at nursery school, and that was back when there were more planets than today! There were nine planets then, (laughs) and I thought that was pretty cool. And as I grew older, I stayed interested in space stuff. The other thing is that I realized I was becoming more rational. I would ask my dad a lot of questions about the world and he just wanted me to shut up, so he would just make stuff up! By the time I was seven years old, I realized what he was doing and I wanted to go find out the truth about things for myself. Even now when I chair proposal reviews, I tell the reviewers: “Do not make stuff up!”

So, your dad practiced reverse psychology on you!

Unknowingly probably! (laughs) It was a labor-saving device for him, to get me to shut up! I went to public school in South Carolina and I really had no idea that you could do anything like this as a career. Sure, this was during Apollo and all that, and you could see the stuff on TV, but there was no real connection. I remember in the fourth grade we were assigned “lab” experiments for science. It was like “go home and do this: measure your latitude”. And the trick was to go out in your backyard, find Polaris, and figure out what your latitude is with this device: (rummages around in junky desk drawer and eventually pulls out a 1950’s era protractor). The idea was using a protractor, there’s a little hole down in the center of the bottom, and you tie a string through that hole and hold it down as a weight, and then you sight along with the protractor and measure the angle where Polaris is, using the string to read that angle, and that is your latitude. I thought that was a pretty cool lab experiment and I did it. No one else in the class got anywhere close, but I figured out what my latitude was from Polaris, so maybe that was a sign. In high school, I studied maths a lot and physics. My physics teacher was the PE (physical education) teacher. He had taken a course or two in physics and was the closest thing we had to a physics teacher. This was a public school in the 1970s in South Carolina. Even then I didn’t realize there was an opportunity for actually working in science. Then I went off to college and eventually made it to UC Santa Cruz, where I had some extended family nearby. I was interested in astronomy and UCSC had Lick Observatory astronomers on their faculty. I took some astronomy classes and realized that I really wanted to do this and so I eventually went to grad school. I got an undergraduate degree in physics which is what they tell astronomers to do, to study physics as an undergrad and then get your Ph.D. in astronomy, so that’s what I did.

So, to the University of Arizona and then Santa Cruz?

No, I was an undergrad at UC Santa Cruz and got my degree in physics there. UC Santa Cruz had a big observational program too, and I started taking upper-division classes from some great astronomers, and that was back when there weren’t many people at Santa Cruz, I think there were about 5,000 undergrads. In my first astronomy class, I think there were four people, which was great because the teacher, Professor Bob Kraft, was close to winning a Nobel prize. He figured out how novae worked and other phenomena and was a great teacher. I had other teachers like that too, and small classes.

Were you already living in the area here, to go to school in Santa Cruz?

I had a brother and a sister living here. So that’s what kind of got me interested in going to Santa Cruz. I went to another university on the East Coast for a year, Duke University, but I realized it wasn’t for me. I didn’t do very good due diligence in researching universities. When I first decided to go to Duke, I asked my best friend in high school, “where are you going?” And he said “I’m going to Duke” and I said, “OK, I’ll do that too!” It was very expensive and rather a closeted or cloistered experience, which I think is fine for some people but I wanted a more public sort of deal, so I came out to Santa Cruz and took several astronomy classes and all the upper-division physics classes. Then I worked for a while in Silicon Valley, after I got my degree, and realized that I was going to be working a long time so I should probably work in a field that is of interest to me, and with people who I think are interesting. I had a very positive experience there and then decided to go to grad school. I was working with another colleague there who I had known beforehand. We both worked at the same company and we met through bike racing in college. He too realized that he was going to be working for a long time, but he came to a different conclusion: he said, “so I should make a lot of money!” So, he stayed in the industry, got a Ph.D. in applied physics from UC Santa Cruz, and was a VP at several high-tech corporations. We get together every now and then and ride our bikes or sail and talk about this, but we each had a different outlook. So, I went to the University of Arizona to get my Ph.D. and have worked in the field of Astronomy since.

That is a very interesting path and an interesting thought process to lay the groundwork for where you are now. Can you describe your path from grad school to NASA Ames?

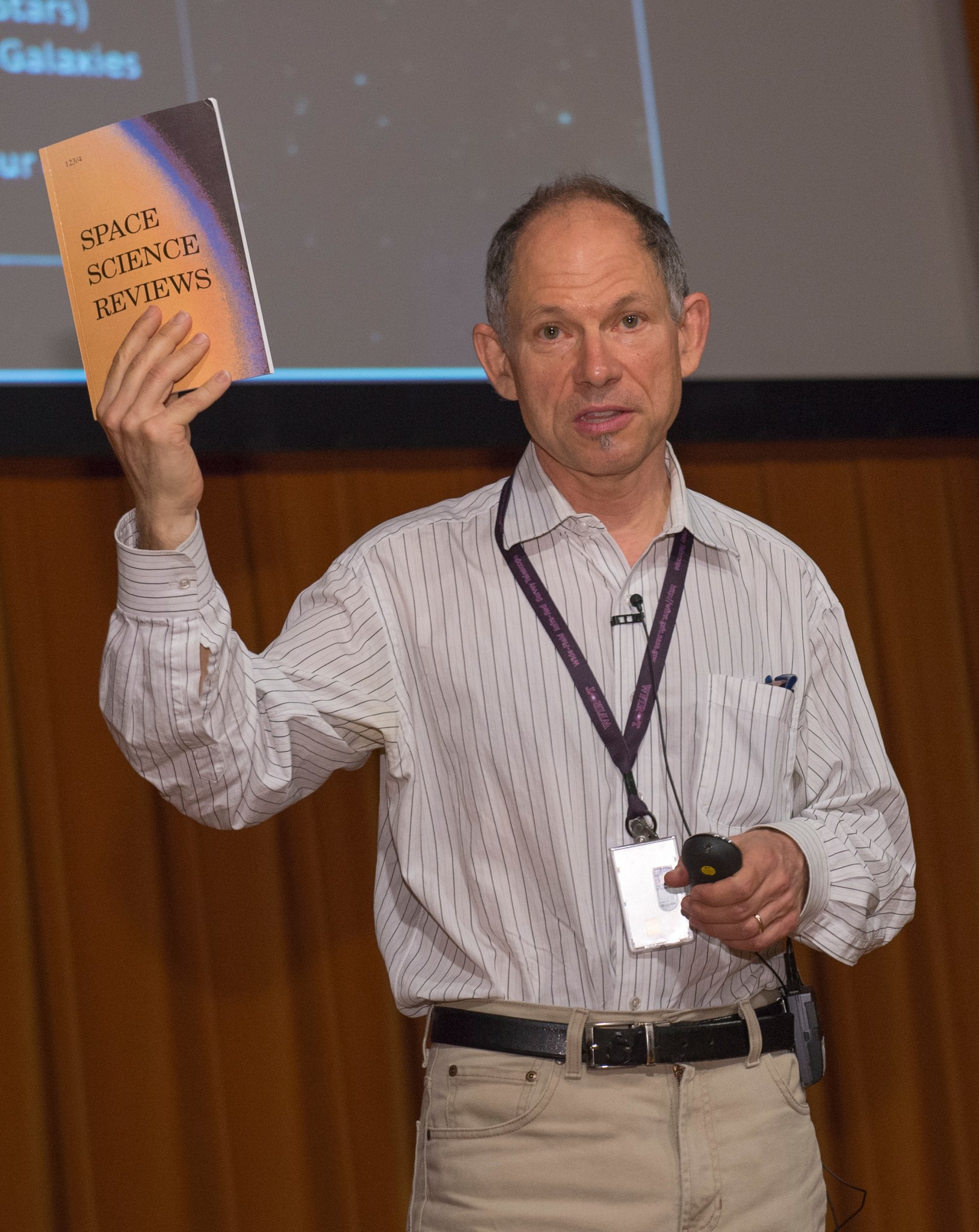

I did an observational astronomy and instrumentation thesis. Arizona was fun but I had an interest in moving back to the Bay Area, so I got an NPP postdoc position at Ames. That was with Fred Wittenborn, and I was doing some instrumentation with him for the Kuiper Observatory. I think Diane Wooden was using it too, and I developed a new detector system and helped them find some errors in optics and that sort of stuff. Working on ground-based and Kuiper instruments was fun, and I came to realize that I wanted to go on into astronomy instrumentation. So, after about a year of my NPP, I left for a position on the research faculty at the University of Hawaii and was a staff astronomer at NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) that the University of Hawaii operates. I was sort of like a glorified postdoc there. I was an instrument developer there, did a lot of science, and had great access to telescopes. Hawaii was a lot of fun and I certainly enjoyed living there but I was hired into a position that supposedly would only be for three years, extendable for another three. They let some people stay on but I didn’t want to stay longer than that. But then I got an opportunity to be the Director of this observatory in Hawaii, so I did that. Dale Cruikshank came from the University of Hawaii by the way, but this was after he had already left. I was Director of the IRTF for a year, basically at a postdoc’s salary, which was not much (laughs), and I was already getting tired of that. My boss was trying to promote me but, unfortunately, was running into trouble. He was kind of getting demoted, so I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Then I got a phone call about this time from NASA Ames asking if I would like to come and be the branch chief of the Astrophysics Branch. They saw that I was the director of this observatory. And I said, “Yeah, that sounds like fun”. I did want to get back to the Bay Area if this Hawaii thing didn’t work out, but I knew it was going to take a while, so I got another job with Lockheed Martin in Palo Alto, and that was really a fantastic experience. I was really there at the right time and I worked on a focal plane instrument for the Spitzer Observatory, for invisible light. It was called the PCRS (Pointing Calibration Reference Sensor). Then I worked on various proposals and the very first week a proposal opportunity came out to propose instrument concepts for the James Webb Space Telescope. This was the summer of 1997, so a long time ago, the previous millennium! I called up some colleagues at the University of Arizona who had developed instruments for Spitzer and said “Hey, would you like to work together on these concepts for James Webb?” So we worked together and one and one-half instruments came out of that. One of them got built by Lockheed Martin in Palo Alto, where I bid, and the principal investigator was Marcia Rieke at the University of Arizona. And then I worked with George Rieke, we were both members of this mid-Infrared science team, on a joint U.S. and European mid-infrared instrument for the James Webb. That was all before coming to Ames and I also worked on some other astronomy stuff. I led the instrumentation part of an Explorer proposal at Lockheed that eventually got selected for flight. It was an astrophysics principal investigator-led mission, for a few hundred million dollars. I developed some other stuff for the Space Interferometry Mission that was being led by JPL but NASA eventually canceled it. Lockheed Martin had a lot of really smart engineers and really good optics people who knew how to make stuff, so it was a lot of fun, it was a great place to be for a year and be able to help get these people, who were very talented, to work on science projects.

You have a lot of experience and your fingers were in a lot of pieces of the astrophysics science pie but how do you justify to the taxpayer, for example, who foots the bill for all this work that we do, why they should invest in the kinds of things you’re doing?

Well, I guess our representatives have decided it’s worthwhile since the money comes through Congress. The science missions of NASA have proven to be some of the most popular endeavors that NASA does. Not only astrophysics, like the Hubble Space Telescope, but also Mars rovers, and Earth science, which is especially practical. I mean farmers want this data, and we need to know what’s happening with the weather. So, I think that goes without question. As for the other things, people have an interest in how we got here and this has proven to be supported by the public. Polls have been done and this is one of the most popular aspects of NASA. It’s more recognizable than some expensive exploration programs that people may not know as much about, maybe more industry-supported, but very popular and they touch common interests, like: what is special about Earth? Are there other places like it? How old is the Universe and how did we get here? These are the big questions that NASA is trying to answer with its science.

That is absolutely true and an eloquent answer. I’ve always felt that NASA’s appeal is more to its engineering side: building the instruments and sending the astronauts up, rather than realizing that the purpose of all the engineering is the exploration and the advancement of human knowledge through science. The science side of NASA seems to be slighted while the big splashy things, the space station, the telescopes, the rovers, etc., get all the attention even though they are actually the means to an end.

I’ve also worked at NASA headquarters and what they care about is getting the money out to the contractors and others who build mission hardware! So, 90% of the money actually goes into the hardware, that’s where the economic interest is, so they have to pay a lot of attention to that. Congress is interested in who is getting money in their districts. But you want to see that this went to something. There are other agencies out there that spend a lot of money and sometimes their programs don’t yield. Like this whole National Reconnaissance Office. They build space telescopes like the Hubble, they use the same mirrors. They had a new ill-conceived spy satellite program back in the late ‘90s and early 2000’s that I blame on PowerPoint. Their thought was “We’re going to do things differently” and the NRO selected a new contractor although they had gone with Lockheed for previous ones. In fact, that’s why Lockheed built the Hubble Space Telescope: they had built spy telescopes that paved the way for all of this right? The NRO picked a new contractor, put billions of dollars into this new program, and it didn’t yield. Can you imagine NASA putting $10 billion into the James Webb and it didn’t yield? That would be a disaster. So, the attention is on the money. Sorry for that digression.

No, no, no! I came up through financial and resources management I remember one exercise we did where we had to report how all the money we received had been spent, by zip code! And I thought to myself that’s an interesting angle. Why would that . . . Oh! Of course! Zipcodes can be correlated with congressional districts! Anyway, so we’re in the middle of this pandemic and one of the questions we ask is what a typical day is like for you? Our days aren’t really typical at the present time but has the pandemic affected your work in a substantive way? Are you able to work remotely pretty much without consequence or is not being able to go into your office, or to a lab, or in the field, causing you any heartburn?

Well, first off, some context: I did a lot of remote work before the pandemic because most of the things I work with are not at NASA Ames. Most of the work I’m doing on the James Webb Space Telescope is based out of NASA Goddard in Greenbelt, Maryland. And the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore is doing the scientific preparation but I work with instrument teams mostly, in Arizona, and some in Palo Alto, that was about ten years ago, and ten countries in Europe. So, I’m used to doing a lot of remote work but I also have a lab project and I’m very disappointed that Ames hasn’t opened up its labs. Our other institutions, our Bay Area institutions, have opened their lab facilities. I was in labs last week at UC Santa Cruz, with people, and so this really has set our back work. I miss the camaraderie of people. People have come and gone. My colleague, Mark Marley, has left. And there are a lot of things that are just not as efficient to do remotely. You can’t go down the hall and say to somebody “How can I do this? Can you help me get this fixed?” A lot of this is in the practical realm. Buying computer stuff has been excruciating. My p-card (Purchase Card) has been taken away and somebody else does the purchases now. Going through lists and not knowing what has come in to give to people at different places has been a logistical nightmare. Christine Martinez has been just fantastic in supporting me in that. So, the answer is that, yeah, it is possible, but I’m getting tired of Zoom. I use Zoom mostly and also Webex, which is what NASA and the projects like to use. I also use BlueJeans for some projects. Then there’s Teams, that we are using now and I also use Google Meet for some science meetings, so, I’m getting quite familiar with these tools. I’ve also chaired the Bay Area Exoplanet meetings, for nine years, and just turned that over to Natasha Batalha. They were a lot more fun to do in person, in terms of working the crowd, getting people together, and also the whole meeting thing. A lot of the value of the meetings was talking with people outside of the talks. I have been going to some meetings in person lately, including some that I’ve actually gotten approval to attend! But that’s a subset of the things that I’ve done! (laughs). I got approval to go to meetings in September and that was great, that was down in SoCal, for the Keck Observatory that NASA is a partner in. And also, I’ve been meeting in person for practicing operations for the James Webb Space Telescope. It’s not going to launch until December, but we have to practice how to operate it. We’ve got a mission control room and we started having practices before the pandemic, the last one in December 2019. We did a lot of going around the world and I have been to Europe doing a lot of stuff for that telescope. In February 2020, I almost didn’t make it back from Spain because of their COVID-19 outbreak, but since then JWST has been having in-person practices again and I’ll be going soon to Baltimore again. Tom Roellig also came to the last one and we have a lot of COVID-19 protocols. During the peak of the pandemic, in early February, I was down at Northrup Grumman in Southern California, where we actually worked on the telescope hardware. So, for mission-critical work, I am able to travel.

Are you saving any commute time during this remote working phase, not having to come into Ames?

Yes, and my dog loves it! We go out and do a 20-minute bike ride/run in the mornings. I live outside of Redwood City, on the peninsula. My dog and I like to go out in the mornings and do “dog” things together (laughs), so that’s my morning commute and it’s been a big improvement (laughs)! My evening commute is much faster: at 6:30 I just close up my computer and go get dinner!

We’ve talked somewhat about your astrophysics work but if you weren’t an astrophysicist for NASA, have you considered what your dream job would be?

I’ve thought about it in the last 10 years and it might sound weird but I really like the field of economics, because what economics does is put value on things, things that are normally abstract. I’m a practical person and I like economic approaches to figuring out whether something is better or not. Such as “what is the environmental impact of electric cars?” You put together models of how people drive, of what the environmental impacts are of electric cars versus fossil fuel cars, you put all this stuff together and it uses the common denominator of money because it’s all about the value of the stuff and you can figure it out. That also applies to sports. Philosophy is also interesting to me, so I have quite a few interests, I guess. I’m in a bike racing club and we have an economics professor at Stanford who has worked on the economics of fitness. It’s a way to apply value in many different parts of life, and I’ve been pretty impressed by that. I read The Economist magazine, and they stick their noses in a lot of things under the guise of economics, and I kind of like that. So, if I’m interested in something that I can take a professional angle on, I think economics is a big umbrella for that.

You mentioned that you’re advising or mentoring several postdocs right now and have over the years. What advice would you give to a young person who would like to pursue a career, not necessarily in astrophysics, but science in general?

What I tell young people and I’ve also had a number of interns at the undergrad level – I’ve been reluctant to take on high school interns – is you should try a lot of things. I encourage people to play out their interests. I tell them that to be successful, at least in astrophysics, it’s different in different fields. In the fields that are actually useful, it is easier to be successful in, or easier at least to get a job, it’s not quite as much of a barrier. But if science is one of the things you want to do most, like number one or two, number two if you’re really smart, then go for it. But keep in mind that it’s not for everybody and that’s OK. That’s also my advice to the faculty. I think people have gotten a little better about it now, realizing that not all their grad students are going to carry on their legacies in the field, and it’s not a waste to put time and money into a grad student. Because you’re going to teach that student something useful and they’re going to go out and do something useful that’s going to make money in this economy and that’s going to help us do our job. That’s also my comment on the state of the profession. Science, like pretty much all professions, is a pyramid scheme. Look at law or medicine: they take advantage of the talent and interests of young people to do a lot of hard work at low wages. This is very similar to the whole student postdoc thing. Established faculty put effort into teaching students to do some work, but after that, they get these postdocs who do not get paid a lot, and they last a few years. It’s a game of musical chairs because there aren’t that many chairs to continue on into faculty jobs. We should acknowledge this, that we are as guilty as all the other fields are, like medicine, law, etc. where people are going to be working really hard for not a lot of pay but in a lot of those other fields, they have the prospects of getting jobs, more jobs than we do. Maybe not in academia but there’s a practical side of law. You don’t have to be a law professor; you can practice law. And you don’t have to be a professor of medicine at Stanford, you can actually help people at Kaiser or something. But in astronomy, in a lot of the science stuff, it’s not so practical. In Earth Science maybe you have more opportunities; but in astrophysics, not so much. So, it is a game of musical chairs. We do exploit the talent and interest of young people, it’s a feature of the profession, so we should support these people when they go off and want to do things outside. I’ve always been a big believer in supporting people who want to do things outside of academia, and I don’t believe they are lost souls. I’ve worked more outside of academia than most people, having worked after my undergrad in Silicon Valley and then at Lockheed Martin for a year before coming to Ames (which isn’t academia anyway). So, I kind of understand a lot of the pros and cons, and the different environments and cultures.

Would you like to share anything about your family? Wife, kids, pets?

Yeah, sure, I met my wife Deb when I was in grad school and we got married in Tucson. Her dad was affiliated with the University of Arizona. She very much likes to garden. We don’t have any kids but she’s a teacher, so she has enough kids at work (laughs)! But we do have a dog, so that’s what life is like around here.

One of my favorite questions, and it sometimes provokes interesting responses is: you’re a very busy person with all your work and such, but what do you do for fun?

Well, some of that is fun, but a lot isn’t, as you know. I’m a man of many interests. I’m a very occasional amateur astronomer – I like to look at stars and planets. I’m a bigger-time cyclist. That was one of the things that kept me sane working at Ames. I could get on my bike and would usually commute from Redwood City to Ames two days a week. It puts some distance between home and work, which is nice.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that is not work-related??

I saw that in your previous interviews. I don’t know how to answer that. I’ve done OK at bike racing, but that isn’t the thing that really keeps me going. I don’t know if I would put any particular thing there except maybe that I try to treat animals well. Community participation is also something that makes me happy and that I’m proud of. It’s through community organizations of different kinds that I get a sense of satisfaction, especially if we get something done.

We also ask who or what inspires you?

The people who keep trudging on in this pandemic inspire me. Definitely frontline workers, but not just them. It’s you folks, who are out there doing this, that I think is a big service to people. It’s all the admins and people who keep life going. They are an inspiration to me. I’m not particularly inspired by a lot of our politicians (laughs), in terms of their achievements, although they do provide some entertainment value! (smiles) I’ve also been inspired by some people in my field, such as Andrea Ghez, who won the Nobel prize in physics last year. Some other of my colleagues are a little more day to day but just to see how they keep on and keep up with publications. It’s the people who keep on plugging through and waking up and saying “What can I do today that’s interesting and worthwhile?” And then going off and doing it.

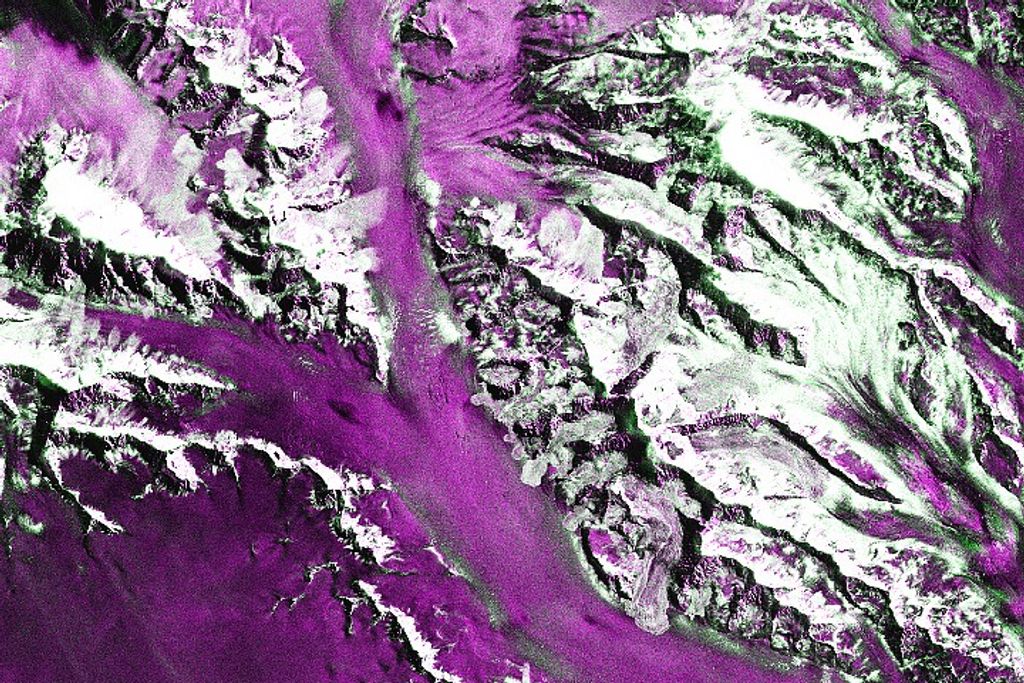

When we post these interviews, we also like to include some pictures to go along with them, that represent your life, your career, things you’ve talked about, and things that are interesting to you. Is there a favorite of space or science image, work-related or not, that you find particularly beautiful, fascinating, interesting, motivational, or something like that, that we might see on the wall of your office for example? And we also ask if you have a favorite quote that you find inspirational, insightful, or clever, that you would like to include because these things paint something of a picture of who you are and what interests you.

Yeah, I had a mentor at the University of Hawaii, Alan Tokunaga, who I believe had been an NRC postdoc at Ames. He always told me: “If we knew what we were doing, then it wouldn’t be research”.

Yes, we’ve heard that one, that’s a good one! (laughs) Sometimes science is not just to find out what we don’t know but to find that we don’t know something and wonder why don’t we know it? Is there anything that you wish we had asked you that we didn’t?

I don’t think so. I could gripe about a lot of stuff but that’s not going to be particularly useful at Ames. (laughs)

I wish that people through this could feel a sense of your animation, your sense of humor, your enthusiasm and your passion for your work because that’s part of getting to know you on a little wider scale. Maybe some of that will come out in the transcript. And I hope one of the pictures you send is of you riding your bike with your dog (laughs), although I don’t know if you can get a selfie on your bike with your dog! (laughs)

Riding a bike with a dog is enough of a handful! Especially if she sees another dog! Another thing about this, as I said in the beginning, is that I enjoy reading these. It’s a great way to learn about other people at Ames, particularly when we can’t be there, and I encourage others to do this.

Thank you, Tom. And I have to compliment you because you have mastered the art of doing a Zoom meeting or a Teams meeting and appearing to look directly at us, in our eyes, which means that you are looking at the camera and not at the screen. You’re the first one that I’ve really noticed, that you just appear to focus right on us personally. (Sara: I noticed that, too, and it made me want to do the same!)

Well, I have to do this a lot with people who are in positions of authority and it’s important to look them in the eye and tell them what you want them to do.

It really is. When I see people looking down or to the side, I think “are you paying attention”? This has been a delight and we appreciate your time. Good luck going forward.

Great, and thanks to both of you. I really enjoyed it.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 10/08/21 virtually.

Learn more about Tom Greene’s work here.