Let’s begin by talking about your childhood, where you’re from, and about your early years, and if there were anything that got you thinking “maybe I could be a researcher, a scientist?”

My parents told me that they remember I wanted to be an archaeologist when I was a child. I personally don’t remember that, but it is true that I had a huge book about Egyptian mythology in my room and I always liked the movie Indiana Jones, I watched it as much as I could. So part of me probably wanted to be like Indiana Jones, and I think this is maybe something that pushed me a little bit toward a scientific career. After all, Indiana Jones is always investigating things, looking for solving mysteries.

What got you then interested in astronomy? Was it looking at the sky at night, or something like that? Or something you read in a book?

Yes, I was interested in astronomy and yes, I had some books, but when I was a teenager, I didn’t think it was really possible to be an astronomer. I thought it was something we used to do in past centuries, or you do it in your free time, but it is not a real job, you know?

However, the fact that my father was a pilot in the French air force and has a passion for all kinds of planes got me interested in aeronautics, and then aerospatial, working on things that fly higher in the sky, further in space, and definitely faster. So for a long time, I wanted to be an engineer in aerospatial. I never thought about following my father’s steps, I mean being a pilot because I’m airsick so this is a pretty big deal when you fly an aircraft. And I’m not talking about being an astronaut, although I would be a pretty good candidate for being an astronaut: when you send astronauts to space you want to study the effects of space on them, on the human body, so you need to send people with symptoms like me. With an astronaut that feels very comfortable in space, you won’t have anything to study, and your mission would fail.

How about your education growing up, related to space?

So I studied aeronautics and astronautics and did a master that included a bit of everything from rocketry and flight dynamics to spacecraft and space mission design. During that time, I did an internship at LATMOS, a French lab that specializes in the observation and study of Earth and planetary atmospheres. Just for the anecdote, my advisor during this internship was Franck Montmessin, who has been a postdoc at Ames in the past. At LATMOS, I worked on an instrument called TIMM-2, designed to study Mars’ atmosphere on-board the Phobos-Grunt mission. The internship went well but not the mission: a few months after my internship the spacecraft was sent into orbit around the Earth but never left to Mars as it was supposed to, due to some issue with the rocket burns. In the end, the spacecraft (and TIMM-2 with it) crashed into the Pacific Ocean. Space is harsh.

So then at some point in your academic career, you reached the place where you needed to make decisions about a graduate degree?

Yes, after the internship and the master, I wanted to continue looking at planets and I got a job as a research engineer at LMD (Dynamic Meteorology Laboratory), which specializes in the numerical simulation of Earth and planetary atmospheres and climates. I worked there with François Forget, who has also been a postdoc at Ames in the past, and Aymeric Spiga, who spent a few months there as well. I worked on the entry, descent, and landing of the Schiaparelli spacecraft, a component of the ExoMars Mission. So this was my second work experience with a spacecraft, and as you may know, Schiaparelli crashed too, this time on the surface of Mars (turned out it was not my fault). So I thought I was cursed. However, many people worked on many space missions, especially on Mars, and a lot of them failed, so I wasn’t probably the only one thinking to be cursed! In the end, during this job I also worked on the InSight mission and this one landed safely and returned plenty of data, so I nailed that one!

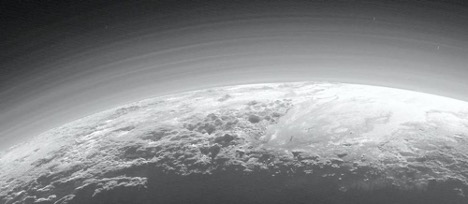

After that I had the opportunity to do a Ph.D. at LMD on the analysis of the atmosphere and ices of Pluto as observed by the New Horizon’s spacecraft, using climate models. This was in October 2014, so the timing was perfect because New Horizons flew by Pluto in July 2015 and returned plenty of new data that I analyzed. By comparing model predictions and observations, I tried to explain the observed pressures, temperatures, to understand the mechanisms at play and how Pluto’s ices and climate evolve in time. Working with the New Horizons team was an amazing and exciting experience because I was taking part in the discovery of a new world, with a lot of pictures that we couldn’t explain at the time, lots of surprises, and new mysteries to solve, for instance, the blue haze in the atmosphere and the flowing nitrogen glacier, that was amazing! So in the end I was like Indiana Jones, doing space archeology, but behind the computer.

So how you got from there with your Ph.D. to connecting with NASA?

At first, I thought NASA would never hire foreigners because all they do is top secret and must not be shared with non-US citizens. But then I learned that it was possible to do a postdoc at NASA after my Ph.D., so it became a serious option. It turned out that my partner was also finishing a Ph.D., in bioinformatics, and she was interested in pursuing her career at Stanford University (!). On my side, I wanted to join NASA Ames to work on the modeling of planetary atmospheres. Stanford University and NASA Ames are very close to each other, so, this quickly became Plan A for us. She wrote a proposal to go to Stanford after her Ph.D., I did the same to go to NASA Ames, and we both got the postdoc position we wanted. Yay! That’s how we came to California, in 2018.

So tell us a little about the work you have done since you joined NASA?

I joined the Mars Climate Modeling team led by Melinda Kahre. Together with this great team, we are modeling the past and present climates of Mars, in order to improve our understanding of what is going on in the atmosphere and on the surface of Mars, and how Mars’ climate works in general. For instance, we investigate how dust storms and clouds form and evolve, what past climate conditions could have permitted liquid water to flow on the surface, how waves propagate in the atmosphere, etc. We also provide a consistent climatic context to explain the observations sent by the different spacecraft in orbit or at the surface of Mars. Our investigations bring some pieces to the big puzzles of planetary science that are the habitability of ancient Mars and the evolution of planetary climates and also contribute to the preparation of future robotic and human exploration of Mars.

What’s your current project? What are you working on now?

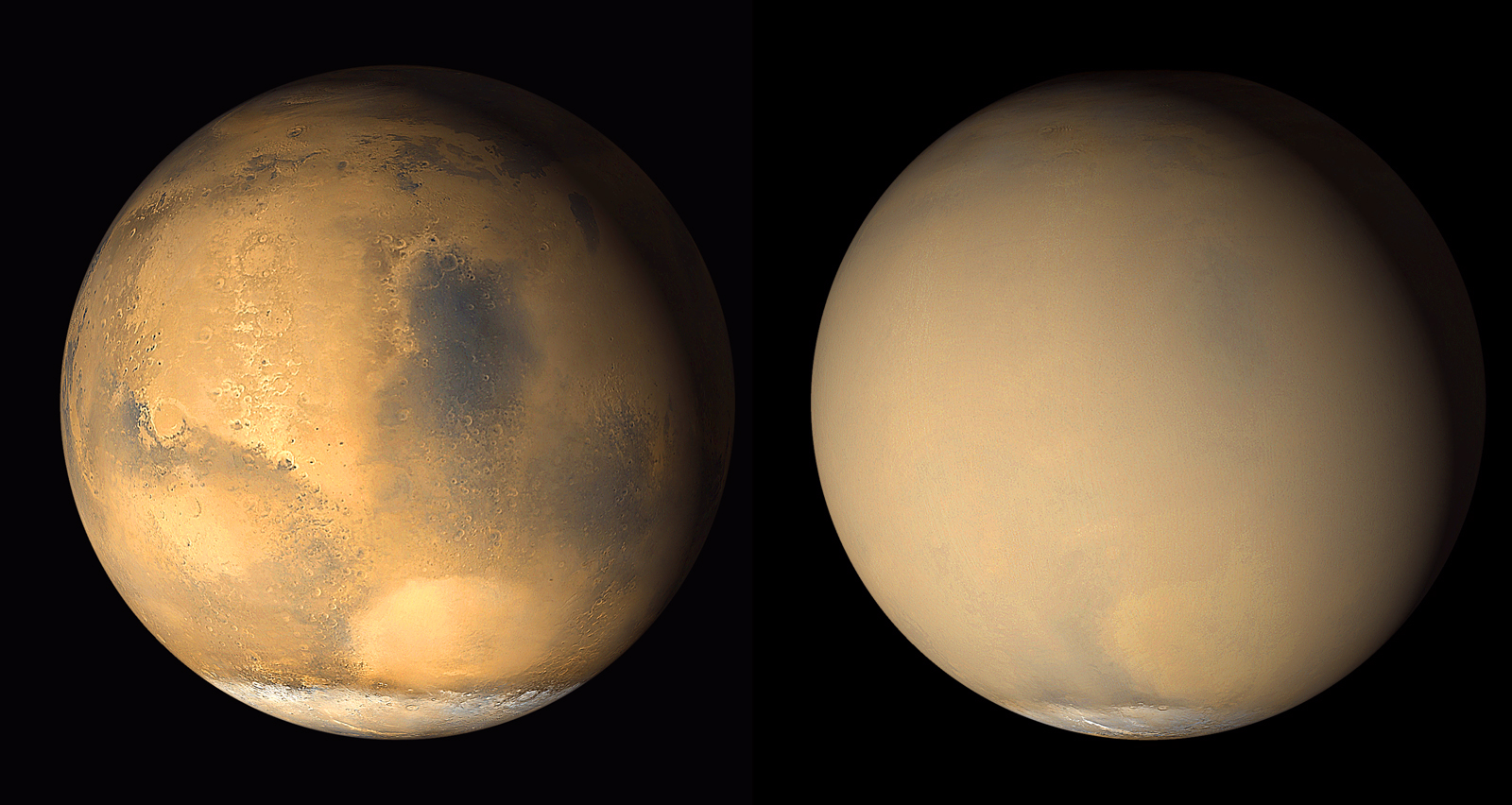

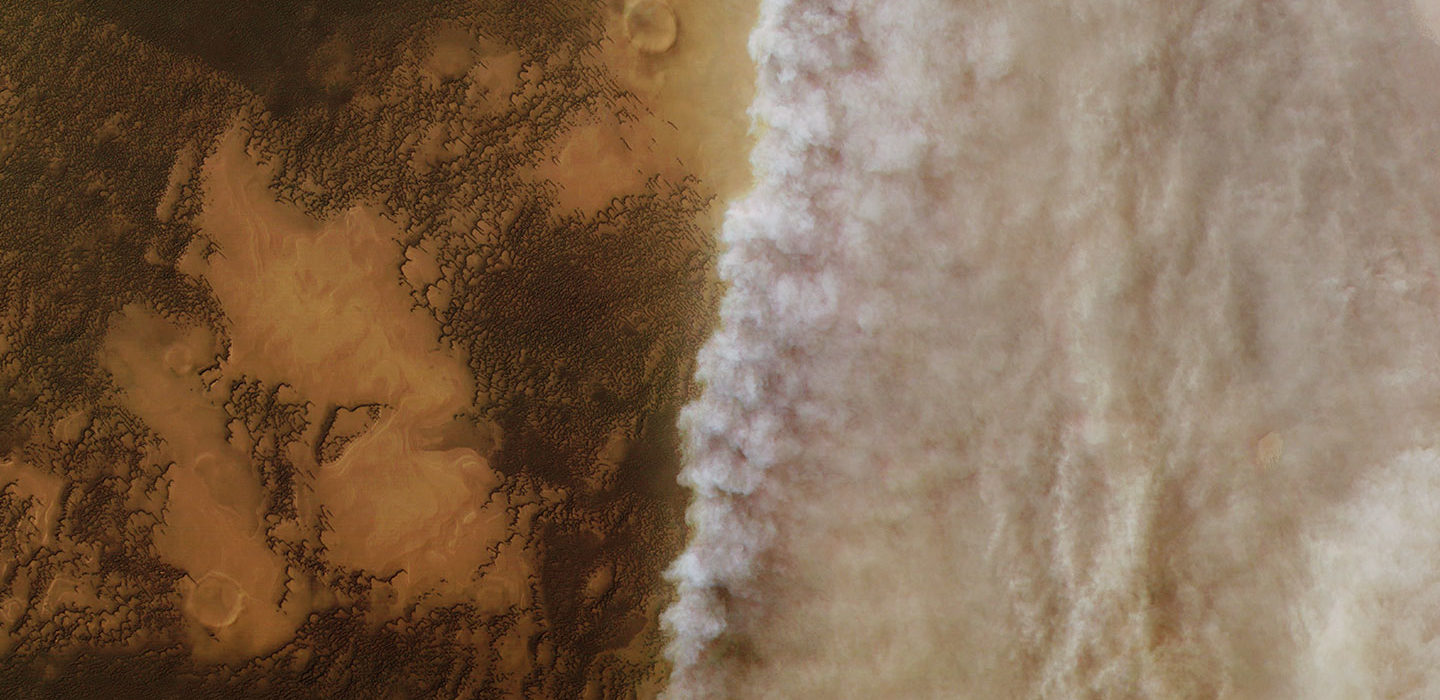

I am currently working on the modeling of global dust storms on Mars. These storms are huge, they inject so much dust into the atmosphere that they mask the entire surface from orbit for several months. That’s how the Opportunity rover died by the way. In 2018, a global dust storm occurred on Mars and the atmosphere was so opaque and for so long that Opportunity could not see the Sun anymore and eventually ran out of battery power. We still don’t know much about these storms, for instance how they form, how to predict them, how they evolve, etc. There is a lot of tricky physics involved, and with my team, we are building a numerical model to simulate those storms and better understand the mechanisms at play.

Since April 2021 I am working at Paris Observatory as an independent researcher. I am excited by this new position, which allows me to keep collaborating on many projects with my colleagues at NASA Ames, which is great!

Why is your project relevant?

First, because these storms are planetary scale events, you can even see them from Earth with a small telescope, but we still do not know how they form. We are missing something, it is a big enigma. Second, because dust storms have a strong impact on the exploration of Mars. They can cover solar panels with dust, damaged instruments, or human spacesuits with dust particle infiltrations. Also, they involve strong winds and wind shear in the atmosphere that can make the landing of a spacecraft onto the surface more difficult. Third, they control the climatology of Mars. Further understanding the storms means further understanding the present and the past climates, which is also important to better understand geologic surface features that originated by involving interactions with the atmosphere.

What’s a typical day like for you?

I start with green tea. Then every day is somewhat different, but it alternates between working on the models, attending meetings, writing papers, proposals (looking for money), going outside for social events, or a little bit of sport. Before the pandemic, I used to go to Ames by bike, I miss that.

What do you enjoy most and least about your job?

I really enjoy the fact that we are always exploring new things, new ideas, and sharing a lot of these with the team and other colleagues. Writing proposals is not my favorite thing, but who likes that?

What advice would you give to a young aspiring student who would like to pursue a career like you are doing? Who says, “Wow, you’re working for NASA and are doing interesting research, how can I do something like that?” What would you tell them to do?

Humm, good question, I guess it depends on the field he/she is interested in, what his/her current level of education is but overall I would give very basic advice, such as know your math, your physics, and I would also give specific ideas on where to go and who to talk to.

OK, now we’re going to throw a curveball a little bit and leave this subject and ask what I think is one of the most interesting questions: what do you do for fun?

Ah, so we remove the past year from this question! I don’t do anything very original. I like to do team sports, I play beach volleyball and soccer here at Ames. Soccer is a complicated sport here because you need to pay attention to the ball but also to the holes in the ground. More seriously, I want to take the opportunity to advocate for the construction of a decent soccer field here! I also started to play tennis here in California, since the U.S. tennis courts are free. You don’t find this in France or in Europe: in general, you have to pay quite a lot of money to have access to a tennis court. Apart from that, I also like to go for hikes, California is a great place for that. We went to Yellowstone recently, it was great! Just like in the movies, we took the car, drove 1,500 kilometers, crossing different states that look like different continents, we camped and saw plenty of wildlife, we had a great time.

We also ask “who or what inspires you?” Who do you find inspiring or motivating?

Well, easy, everything Mankind has done in space is very inspiring and motivating. Then I have been impressed and inspired by many people of the New Horizons team, as well as by my Ph.D. and postdoc advisors. In the world, there are bad and good advisors … I was very lucky to have very nice and excellent advisors so far.

Do you have a favorite image?

I have a lot of favorite images, but if I have to keep only one, it would be that one about Pluto, sent by New Horizons during the 2015 flyby. You can see Pluto’s atmosphere, betrayed by the presence of a blue haze, formed by a complex photochemistry of gaseous nitrogen and methane. The haze is composed of many thin layers, likely the result of atmospheric waves propagating vertically through the atmosphere. On the surface lies a nitrogen glacier, with features indicative of glacial flow, something previously unseen outside Earth. The glacier lies in a flat depression surrounded by surprisingly tall mountains! This landscape is just amazing!

For the anecdote, I’ve been gathering images of planets and moons and did a quiz with it on my webpage, and I invite anybody to take the quiz and guess what planetary object is shown for each image. It’s sometimes tricky!

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 01/20/21